There is no theatre without the playwright. It is our duty to confront the blank page and create the story that will be handed over the producer, director, cast, crew, and audience. With the recent strikes, closings of theatres, the resignations, the restructuring, the reorganizing, the budget cuts, the challenges of the pandemic, and all the increases in the cost of living, artists are working hard to find new processes of making and disseminating their work. As we strive to unlearn old systems that are tied to supremacist culture, I’ve witnessed a trend that playwrights from historically marginalized communities are predominately the conduits of change.

In my work as a New York City-based theatremaker since 2015, I’ve had the pleasure and pain of doing a lot of fast and furious festival work (which could be called guerilla theatre) over the years. Writing short plays is a great way for emerging playwrights to not only get practice and experience, but also to connect directly with theatres, audiences, and other artists.

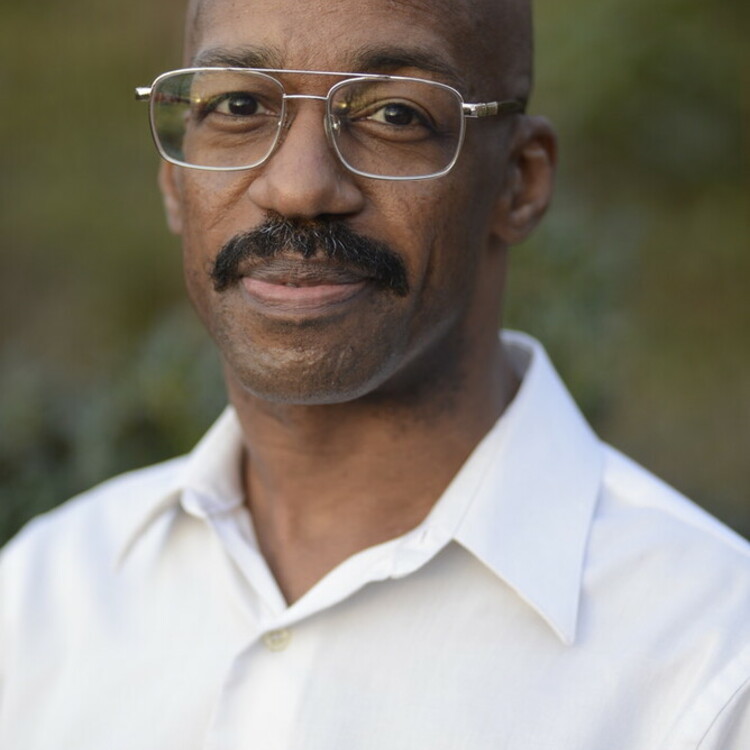

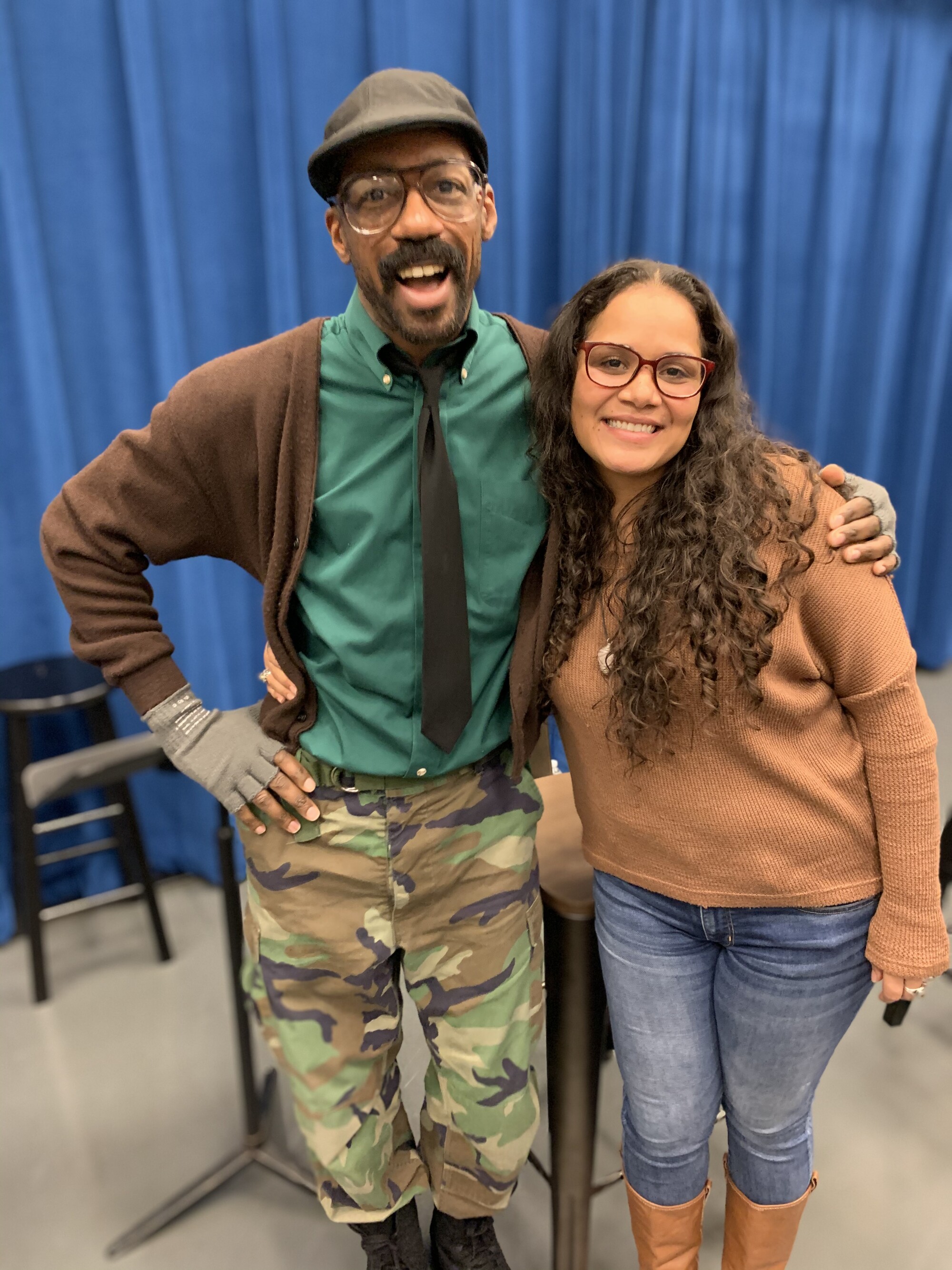

I texted with three fellow playwrights I’ve met through this festival work who are making a difference: Christin Eve Cato, Alexis Roblan, and Marcus Scott—all accomplished multi-hyphenates who have been making groundbreaking work not only within New York City, but outside of the city and through other means of creative writing.

It starts with the writing! These characters we create need to start and continue the conversation about inclusion.

I got to know all three writers within the same fast-paced space—working for the LGBTQIA+; Black, Indigenous, person of color (BIPOC); and female/femme-led Exquisite Corpse Company (ECC), which focuses on presenting and supporting the work of folks from those underinvested communities.

I met Alexis first in 2017. She presented a piece that was written and directed within twenty-four hours for ECC that delved into the darker side of theology, and I warmed up to her play immediately—an absurd comedy about a quirky priest on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

Alexis’s show at the Tank NYC in 2021, entitled Samuel, was a remarkable departure from traditional methodologies of theatre presentation. It went up right around the time theatres reopened after the lockdowns—when there wasn’t an adherence to the old Western theatre style of sit down and shut up in the dark while you’re watching something happen on stage. We were lead through a veritable memory-haunted house of theatrical motifs that handled storytelling in an innovative and masterful way, spearheaded by scenic designer You-Shin Chen. Samuel opened the doors to people who don’t go to the theatre often; I attended previews and the run, and I noticed it was frequented by a large number of younger folks on dates and rendezvous with friends because you could interact with and within the space.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here