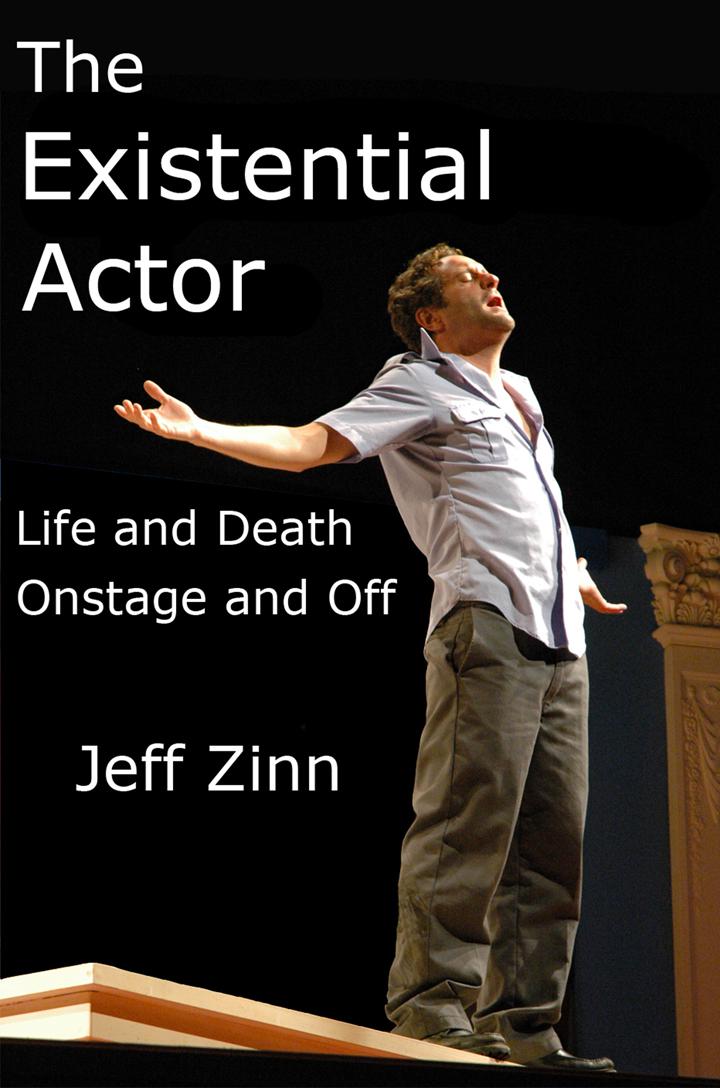

Jeff Zinn

The Existential Actor

I have a special attachment to the work of Director Jeff Zinn: I edited his new book, The Existential Actor: Life and Death on Stage and Off. In it, Zinn writes with casual fluency about the psychology and history of training actors. Zinn proposes that if actors understood that our quest for identity is a shield against the certain knowledge of death, if actors could articulate their own heroic journeys and their own given shapes—the ones given to them by the civilization in which we live—they might come closer to “the holy grail of acting technique,” the surrender to authentic emotion.

Zinn’s book reaches back to the great waves of actor training and philosophical theories about acting—Aristotle; Diderot; Delsarte; Stanislavski; and the postmoderns: Artaud, Brecht, Grotowski, Wilson, Overlie, and Bogart—and ties them to the cultural context in which each crested. The book speaks to actors, directors, and dramaturgs; and it may be useful to audiences—and critics—curious about why some plays offer a thrilling experience while others, though craftsmanlike and competent, leave them unmoved. What Zinn has to say about the artist, most especially his discussion of self-constructed identity, may be as illuminating for poets and visual artists as it is for actors.

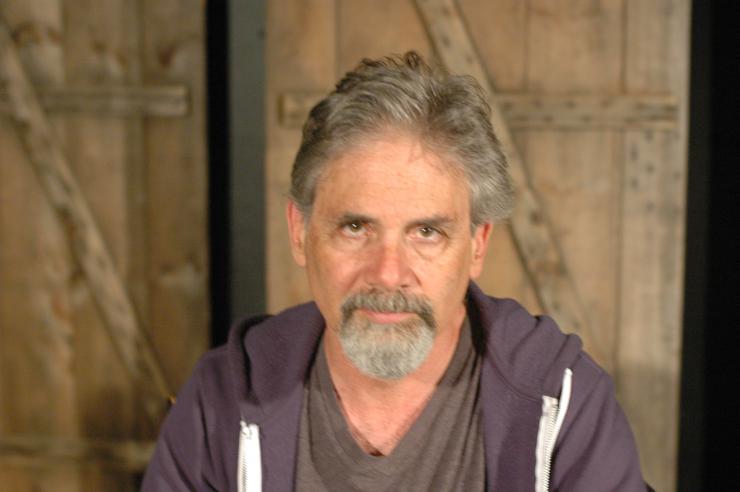

Artistic director of Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater (WHAT) for two decades before returning to acting and freelance directing two years ago, Zinn teaches at Clark University and Worcester Polytechnic Institute, an engineering school with a thriving theatre program and new plays festival. This month, Smith & Kraus publishes his book.

In all the time we worked together, about nine months through the fall and winter of 2013–2014, Zinn and I never met face-to-face. Last June, we met for the first time at his beach house in Wellfleet, a small town on the northwest side of Cape Cod.

The night before we met, I saw Zinn in Uncle Vanya, directed by Robert Kropf, produced by Harbor Stage, a ninety-seat theatre in Wellfleet. Zinn played Serebriakov, the professor.

Jayne Benjulian: I heard some Jeff Zinn on death when you were speaking the professor’s lines.

Jeff Zinn: Absolutely. It was a great testing ground for me to approach this role and a challenge to myself to put to work the ideas that I have written about in the book.

Jayne: You wrote, “Death—by suicide, by duel, by disease, by the axe—continually hovers in the background of all Chekhov’s plays providing an essential reminder of mortality to the audience.”

Jeff: Here’s a guy, Serebriakov, who is facing death, and he’s looking back at his career… Serebriakov imagines that he has contributed something, that he has had an impact on the world and on his field, but Vanya says Serebriakov has no original ideas. It’s easy to imagine that the professor looks back on his career, and it’s kind of empty. Is there any meaning in what he’s done? That’s absolutely in the text.

On the technique side of it, it was a challenge because I’m too young for the role, and Bob [Robert Kropf] was pushing me to make him older and frailer, and what I felt was that as I loaded up on all of these shape elements, that was the tension. I’m layering up all this old man stuff, and yet I want to find the truth of the character, and I want it to be authentic. It was a battle between shape and surrender.

Jayne: “Shape,” as you define it, is what our culture and family give us and how, in forming ourselves with that material, we appear to the world: language, body, how we walk, talk, eat, what we believe about death. “Surrender” is authentic emotion.

Jeff: Bob said he wanted to see Serebriakov’s vulnerability. The character spends so much time ranting and raving; it’s a kind of armor, so it was a challenge to open him up and express those feelings of desperation and failure. It was wonderful to have that challenge as an actor and play with those ideas I’ve been immersed in for so long.

Jayne: You say in the book that traditional acting exercises that stimulate the imagination can help us find pathways into a character. But they also reinforce the notion that the characters we portray are fundamentally different than ourselves, so that portraying them requires some kind of technical bridge. How did you prepare to carry life and death urgency to the role?

Jeff: First of all, there was the technical challenge of memorization, of learning it. Bob asked me to come in off-book to first rehearsal, and so I did. It was freeing to go into rehearsal off-book so I could focus on other things, and I did what I recommend in the book. I approached the elements separately. I took the physical characteristics of voice and posture and cadence and let the language inform the character. It didn’t take much to do that, but my greatest fear was that I would be like the high school kid playing a caricature of a gruff, aged voice—you layer up all that shape stuff and have a cartoon. Having the text, having the shape, for me the nightly struggle is about surrender, about being open, being vulnerable, shedding the psychological armor that shape provides, and that is hard. There are people who have the capacity to be available; it’s not easy for me. Knowing that the other elements are in place, the shape, what his objectives and actions are as he moves through the play, I can focus on the surrender piece and try to move myself into a place of openness and vulnerability.

Jayne: Do you think Chekhov has anything to teach the current generation of playwrights and directors?

Jeff: It all happens in the spaces between. He does such a beautiful job of painting behavior and life flowing, people come and go, and not much happens, yet everything happens. And he’s not afraid of engaging big passions. One of the things I love in Uncle Vanya: there’s this huge explosion in Act 3. Vanya tries to shoot me, and we’re screaming at each other, and then I come on in Act 4, and let’s leave that in the past. I love that moment where I say goodbye and everything is forgiven. It’s Russian. There is a culture of permission of expressive behavior. The American equivalent is once you have that explosion, you can never put it back together. The family tensions build up to fireworks, and then the family is shattered. But in Chekhov, there is forgiveness.

Jayne: You live on The Cape. Did you ever consider staying full-time in New York to direct?

Jeff: I started transitioning from acting to directing around 1981. I had done some directing, but what I learned about surrender for the actor was so revelatory to me, of what it meant to let go, to tap into some deep emotional life, I thought it would be interesting to return to directing with this in my knowledge base. I had something to bring to the actors that I hadn’t had before. The offer at WHAT on Cape Cod was an opportunity to put down roots and have an artistic home.

Jayne: How do you conceive of the endeavor of directing a play?

Jeff: Part of the job of the director is managing all of the different elements together, not least of which is helping the actors and working with the text. Peeling an onion. You are constantly finding new possibilities for the characters and the actors. Sometimes you work on a play, and you can get bored with it because it’s not an onion; it’s a soccer ball.

I never go into a play with a big concept. It’s always about making it up and exploring with the actors as we go along. Helping the actors to find what they need to do. And I am guided by my philosophy in terms of finding the real stakes. At the heart of it, as we close in, I am evaluating, are the stakes high enough? Does this play have the impact that it wants to have, and if not, why not? Sometimes I am more consciously helping the actors find the deeper motivating ideas there. What’s really at stake for them? How do we make it life and death?

Jayne: That is your book’s opening sentence: “When we go to the theatre we want what happens onstage to be a matter of life and death.”

Jeff: Maybe people are not all consciously going to the theatre to confront issues of life and death. But I think if they don’t find that the stakes are high enough, they may be entertained, but at the end of it, it’s a little empty. Even if it’s a comedy, it will be funnier if the stakes are higher. We can laugh at people who are furiously going after something because for them it’s a matter of life and death, and it’s absurd for us to watch them.

Jayne: The idea of high stakes is so central to everything you believe about theatre that it’s worth asking: What do you mean?

Jeff: Every character in every play is working with a sense of himself or herself and an identity which has been forged on some level in reaction to their awareness of their mortality. If you dig into any character, he or she is trying to be somebody. Trying to live a life that has meaning, and the flip side of meaning is meaninglessness. There must be a reason why I’m here. This sense of identity is always fighting against the void. It’s pure Beckett. On the other side is always the darkness. In some cases, we find a character whose identity has been shattered, and the journey of the character is to rediscover an identity.

Jayne: How do you work with actors to realize that, because you surely don’t tell them all that.

Jeff: You can ask: Why is what this person wants important to him? Think about your own journey and your own sense of who you are and what you are trying to accomplish and how important it is to you. There isn’t a person alive who isn’t trying to find meaning and has not constructed a heroic narrative for herself. Sometimes in rehearsal, I say, tell us your story. Who are you? You’ve got this idea of who you are and what you want to be. How do you know you are succeeding at that? Who validates that idea of yourself? How do we translate to the character, and who are the transactional figures in the character’s world they are looking to for validation? As my own character in Vanya, I am surrounded by characters who are not giving me the validation I need. I’ve got this young wife: in that first scene that I have with her, I say, “I see, I see everything.” I know she’s repulsed by me. What does that do to his sense of himself that he’s repulsive to his beautiful young wife? That’s tough. You don’t skip over that.

Jayne: I want to hear you talk about yourself as an artist.

Jeff: No, you talk about me as an artist!

Jayne: In the book you discuss cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker’s premise that the artist uses art to find a solution to the problem of existence. And it’s because the artist does not accept the collective solution, she has to fashion her own, and that’s your definition of an artist: someone who is fashioning, against the collective definition of identity, her own identity.

Jeff: Very well put.

Jayne: It’s a paraphrase of your words. Can you talk about yourself in those terms?

Jeff: The people I most admire as artists have a sense of dissatisfaction with what they produce, and that’s what drives them further. That’s where the cliché of the tortured artist finds some deeper meaning. The work is never good enough. I don’t know that I suffer in that way. Sometimes I direct something and I’m pretty happy with it. Do I get complacent? Yes, sometimes I do. But I like to push beyond. You could always use another week of rehearsal. But listen, as an actor I am never happy. Every time you go out, it’s a toboggan run. You’re zig-zagging past the beat and sometimes you hit it and sometimes you mess up. You’re out of it and you’re trying to find your way back into it. It’s such a struggle. As an artist I am always reaching to do better. I have a comfortable life that makes me happy, so I am not as tortured as some. But I am not content: I would love to have more opportunities to do what I do. This is a very tough competitive business/world that we inhabit. There’s the art side and then there’s the hustle—self-promotion—side. There’s Serebriakov, “plagued by the success of others and obsessed with my own death.”

Jayne: And now, your book.

Jeff: I’ve been writing it for twenty years. I sat down to write the first draft the winter that my wife was pregnant with my daughter who is now about to turn twenty. I struggled mightily with how to write it for a very long time. It was also impacted by what else I was doing in my life, building and running a theatre company and raising a family. I was churning in my head: What do I do with these ideas? I must have written the introduction fifty times because I always felt that this book would be like a wall, and if the bottom tier of bricks was not right, then the whole thing would topple over. There were these interwoven threads—the four elements—action, shape, transaction, surrender—already simmering in my consciousness when I discovered Becker. When I glimpsed the possibility of something that could unify it all, I felt compelled to pursue that idea, teach it, write about it.

Jayne: I admire your self-awareness in the book about your own heroic journey.

Jeff: I had this horrible sense of incompletion and failure for years that I had this idea in my head and I wasn’t doing it. My New Year’s resolution for twenty years was to write the book.

Jayne: Why was it so important?

Jeff: A friend who works in theatre said, “OK, what do you want? Do you want to sell a million copies? Do you want to be an acting guru? Or do you just want to get your spit out before you die?” And I said, “the last one.”

A friend said, ‘OK, what do you want? Do you want to sell a million copies? Do you want to be an acting guru? Or do you just want to get your spit out before you die?’ And I said, ‘the last one.’

Jayne: Here’s what you write about Sonya’s final speech in Uncle Vanya:

The need for work, for a useful vocation, for a meaningful causa sui project that creates meaning beyond itself recurs throughout all of the plays. Work offers a narrative for our journey toward death, or away from it if we are in denial.

What part of your life’s “project” is incomplete?

Jeff: My father [Zinn is the son of the historian and social activist Howard Zinn, author of A People’s History of the United States: 1492 to Present] was incredibly productive and a very big figure to the world, known in movement circles but not in the public consciousness until the late 1980s. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to say that I am influenced to some degree by my father’s fame and influence, and that inevitably becomes a bar for success. That’s what it means to be successful in the world, to achieve a certain kind of fame.

The need for work, for a useful vocation, for a meaningful causa sui project that creates meaning beyond itself recurs throughout all of the Chekhov plays. Work offers a narrative for our journey toward death, or away from it if we are in denial.

Jayne: Do you think that death and mortality—and therefore your life’s project—have a greater sense of urgency for you since your father died?

Jeff: I’m certain that his brilliance and high level of accomplishment had a great deal to do with the formation of my particular shape and set the bar quite high for me in terms of what I might accomplish with my life. Has that intensified with his death? Perhaps, but on the other hand, with him gone, I feel I am more my own person now.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here