Looking for Another Way

Jeffrey Mosser: Dear artists, welcome to another episode of From the Ground Up podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. I’m your host, Jeffrey Mosser, recording from the ancestral homeland of the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee, now known as Milwaukee, Wisconsin. These episodes are shared digitally to the internet. Let’s take a moment to consider the legacy of colonization embedded within the technology, structure, and ways of thinking that we use every day. We are using equipment and high-speed internet not available in many Indigenous communities. Even the technologies that are central to much of the work we make leave a significant carbon footprint contributing to climate change that disproportionately affects Indigenous people worldwide. I invite you to join me in acknowledging the truth and violence perpetrated in the name of this country, as well as our shared responsibility to make good of this time and for each of us to consider our roles and reconciliation, decolonization, and allyship.

Dear artists, we’re going to jump right into it today with Karen Malpede, a playwright who’s had a significant career in the contemporary theatre in the avant-garde theatremaking scene in New York City. As I mentioned in the call, for a very long time I’ve had Three Works by the Open Theater on my bedside as a series of scripts that reminds me how important it is to record our work. Karen, having written the introduction to it, was a name that I’ve seen come up over and over in my career, and I thought it might be great to reach out to her to find out a bit more about the time and place of New York City that Open Theater was working in. A major part of our conversation revolves around George Bartenieff, who passed on July 30, 2022, just prior to our recording. He was the founder of Theater for the New City, an actor, and so much more, and I’ll be sure to put the details about him on the show page for you to dig into. If you really want to know about him, I hope you’ll observe his celebration through the La MaMa Coffee House Chronicles episode on YouTube, which I’ll be sure to put in the show notes.

Karen cites several companies and people along the way, and you don’t have to know them, but I do want to share them here, and I’ll also add some links to them on the show page so you can do some deep dives on your own, including members of the Living Theatre and Open Theater, Joseph Chaikin, Judith Malina, and Julian Beck. She also mentions figures such as Burl Hash, Merrill Brockway, and the co-founder of Bread and Puppet Theater Peter Schumann. She also mentions some real touchstone theatre pieces, including Peter Handke’s Mutation Show and Amiri Baraka’s Slave Ship.

Finally, please note that I had some audio trouble on my end once again, you’ll note that my voice is a bit choppy in here, and so I offer you my sincere apologies and hope to have this resolved for season four. Okay, here we go with Karen Malpede, joining us from Lenape land, now known as Brooklyn, New York on October 5, 2022.

What we meant by “collaborative” is that you have control over your art and it becomes, then, part of a larger whole, a larger experience.

Jeffrey: Karen, thank you so much for your time today. I really appreciate this moment and us being able to share this time together to talk about it all. And you’re a playwright, a director, a teacher, a socially driven artist, so much more… So what is it about all these things? How do these all get tied together to drive you as an artist?

Karen Malpede: What else would I be doing? I guess, the earliest… I would go back say to high school where I discovered Jean Genet—The Blacks—and then to college where I studied almost extensively, not quite, but a lot of Irish theatre and Irish literature and Irish history, and saw very clearly how the Abbey Theatre, for instance—a poets’ theatre, which is what our theatre is, it’s a poets’ theatre—influenced the historical trajectory of a free Ireland—politically, emotionally, spiritually—and really created a culture—helped create a culture, Yates and Augusta Gregory and the others, but they were the primary drivers of the Abbey Theatre—it helped create a culture that gave insight and strength and beauty to people who had been oppressed forever by the English colonizers. That was a very important— and of course the work was beautiful, and so many—Shaw, O’Casey, Synge— so many people came out of it. Augusta Gregory too, the first woman playwright I encountered in my life who worked very closely with Yates on his plays and he on hers, giving feedback and listening and stuff.

So that was very formative. And then when I went to graduate school, well then the Vietnam War happened, and all the assassinations in a row, and I was part of the early teach-ins. I went to the University of Wisconsin and then I went to Columbia, so two hotbeds of anti-war activism, but at Wisconsin I was working on the Daily Cardinal, which was the student newspaper, and we were being investigated as being communists by the Wisconsin State Legislature, and some of the editors—I was the arts writer and editor for a while—some of the editors, the news editors for instance and the editor-in-chief, were really under attack. So there was that, and then there were the early teach-ins, which we should be having about the war in Ukraine and nuclear weapons and other things right now.

But there were early teach-ins that were extracurricular. They weren’t part of classes, but they were the socially engaged professors teaching the history of the Vietnam engagement and the lies and the immorality of it. So I got educated in that way, and then I was part of the early anti-war marches at University of Wisconsin, so I became an anti-war activist. So that influenced what kind of— They all got fired if they didn’t have tenure, but there were a lot of socialists or left-wing professors, young people, at the University of Wisconsin, and another course that influenced me a lot as I think back on it was German theatre between the wars. So Toller and Kaiser and those guys. Brecht started then. I was drawn to that kind of theatre, both the Irish and the German.

And then when I went to Columbia and studied— I was in the dramatic literature program. I didn’t want to study playwriting with two men actually. I didn’t trust them and I didn’t trust myself either. I wasn’t writing plays then. I was introduced by Albert Bermel, who was one of my professors. He said, “Why don’t you look at the Theatre Union for your MFA thesis?” And he knew my interests and he knew some people in the Theatre Union. Theatre Union is in People’s Theatre in Amerika, was a left-wing theatre, and so I wrote my thesis on that, and that morphed into the book People’s Theatre in Amerika. So I then researched those theatres and researched the contemporary versions—the Living Theatre, the Open Theater, and the Bread and Puppet primarily—those great theatres, and wrote chapters about each of them. After the book was published, right after the book was published, Judith Malina read it and reviewed it for a magazine called Liberation, which was the War Resisters League. Very interesting literary magazine, Paul Goodman wrote for it, Barbara Deming, a lot of very interesting political writers, pacifist writers.

Anyway, she fell in love with the book. She came to meet me. Julian had read it. Joe Chaikin had read it. The only person who hadn’t read it was Peter [Schumann]—People’s Theatre in Amerika. Peter was one of George’s oldest friends. They had met in the sixties at an anti-war demonstration or something in the park. They were both performing in Central Park, and I knew Peter, I knew his work much more than I knew him, but I knew him through George and especially in later life cause we would always see Peter every year when he came to perform, but I always knew he had never read People’s Theatre. You know, so what.

When we scattered George’s ashes in the Bread and Puppet memorial grove, and then a few nights later, I got a call and it was Peter and he said, “I went to my bookshelf and I found your book,” and he said, “It’s amazing. Even then you knew the importance of the proletariat, even when you were a student,” he said. “You knew the importance of the proletariat.”

So we got to talk about People’s and I was affirmed in my suspicion that he’d never read the book, but now he has, or at least part of it. But that book really, because these people sought me out—Judith and Julian and Joe—and pulled me into their circle, that book really changed my life. Not just the writing of it, which was fascinating of course, because that history was evaporating, literally in my hands I would hold newspaper articles in my hands at the library at Lincoln Center that weren’t well preserved, and they would crumble as I read them. They would fall apart literally as I was taking notes on them. And I was just at a theatre conference, God forbid, in New Orleans, and two guys, young men, maybe even younger than you, I don’t know your age, came up to me and said they were teaching those two books and that without them, they would not have known any of this history.

And it seemed like they were spending their life researching the thirties and probably the twenties and thirties. That was interesting too. But yeah, it was a revelation to me, and I became friends with Jack Lawson, who was one— They were all dying, all the playwrights of the twenties and thirties. Jack lived a pretty long time, and as an unrepentant Stalinist, which is not my politics, but we were friends. He was a pretty vital, lovely person.

Jeffrey: Yeah, thank you for that. I think that gives some real insight into your social justice and environmental work that you’re currently doing and have always been doing. So thank you for sharing all of that. You’ve invoked some of the names of Joe Chaikin and the folks from Open Theater, and one of the reasons that I wanted to really reach out to you is, as I explained in my email, but for a long time, and I still have Three Works by the Open Theater sitting on my bedside. It is something that I have thought about for a long— that book has lived with me for a very long time, Karen, and so it really is a pleasure for me to talk to you right now. And that book is maybe why we’re sitting here and your previous book is something that we all will, I hope all of our readers, will pick up and take a look at as well. Since you’ve invoked their names, I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about how you contribute into that work.

Karen: The Open Theater was not a place for writers. I wanted to be a playwright. I wasn’t yet a playwright when I wrote that book. I wanted to document the work, and Joe and I conceived the book. It was done completely without money. Nobody got paid, nobody ever got paid for anything, but it was a collection of really major artists because Joe had a facility for attracting people like Mary Ellen Mark, like Inge Morath, like Max Waldman, and they were all major photographers and artists and friends of Joe’s and devotees of the Open Theater, and everybody contributed their work free, as I said, and I wrote the introduction and Joe wrote the preface, I guess. So it was really a labor of love, which is mainly how everything gets done, if it gets done in the socially conscious theatre world. And actually, there’s a funny story from this too, how things lead to things.

But after I did this book, I wrote an article on Peter Handke’s Mutation Show, which was being done at the Chelsea Theater Center, which was another major theatre, which also did Genet’s The Screens, a really wonderful production of The Screens, and did Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones’s Slave Ship and toured it in Europe. And my first theatre was co-founded with Burl Hash, who was one of the producers of Chelsea Theater Center. We met during this time. After I wrote this book, I wrote an article about Peter Handke and Mutation Show, and it was published in Theater Magazine, and I was at a party one night with the Open Theater gang, and a guy came up to me and handed me his card, and it was Merrill Brockway, he was a producer. This was a different world obviously, he was a producer of Camera Three at CBS, which was their Sunday morning art show, and he wanted to turn my article into a four-part series.

So we filmed Peter Handke’s Kaspar at Chelsea. We filmed Mutation Show in a studio, filming a play is a whole other thing with many cameras and camera angles. And then the third part of it, I had linked this work to Noam Chomsky’s early work in linguistics and I interviewed Noam and Stanley Aronowitz, who was a cohort of Noam’s and a friend of mine, on the lawn at MIT about what they were calling then libertarian socialism and linguistics, Noam’s early linguistics theories, which I followed all my life. The show aired—four… I don’t have the video, I wonder if any has—four parts, the plays, and this conversation. Years later when I was doing Prophecy, which is my play about the Iraq war and veteran suicide and the link between Vietnam and Iraq, et cetera, Najla Said was in the play, and Noam was giving the Edward Said memorial lecture that year at Columbia.

Noam was giving the lecture, and George and I were coming up the aisle to find our seats in this very crowded lecture hall, and Noam was going down to give the talk, and we recognized each other. He recognized me. It was years later, it was 2000— probably 2008 or so. The real rewards of the work I’ve done have not been money, where there’s been very little of money, very little few grants, no awards to speak of… [They] have been the people I’ve met. The people I’ve met who really came out in force around grieving and memorializing George, a community that stretches through decades.

Jeffrey: One thing that you had mentioned in an email to me was the conversation between you and Joe Chaikin about the line that you basically says— you explained to him as he was leaving the Open Theater, you told him that he was the playwright of the Open Theater, and you also just expressed a moment ago that they were so not play-based or so not written word–based.

Karen: What I said to Joe was, “You determined the structure and the content of the pieces, and therefore you were the playwright of the Open Theater.” And he didn’t bat an eye. And he said, “Of course I was.” He knew that. I knew that. The writers who wrote for him, who many, Susan Yankowitz and Jean-Claude [van Itallie]— and Sam didn’t really write for Joe, Sam wrote his own plays, but Joe was involved with Sam’s work. But the writers who wrote for the Open Theater were just filling in the gaps. They were— “We need some words here.” And once I was in a rehearsal with them, and several of the writers brought in their pages, and Joe had a handful of pages of written work, and he threw it on the floor and he said to the cast, the company, “Does anybody want any of this?” I would never go into that... I didn’t go into the Living Theatre when they begged me to join the Living Theatre

And I did not want to write for the Open Theater either, because I wanted to write plays, meaning, as I said to Joe, determining the structure and the content of the work, which is what he did. And he knew the centrality of his role. When the Open Theater disbanded, sort of abruptly, he had had enough, and he called the shot, “We’re ending it.” He then gathered in his apartment at Westbeth, I don’t know, we had three or four or five meetings, people who he wanted to hear from, including the young woman, Eleanor, who directed Lament for Three Women; me; Jean-Claude; and I don’t know who else was there to discuss, “What do we do now? Now I’ve ended the Open Theater, what happens to the theatre?”

And he and I agreed that one of the things the Open Theater had done—and of course the Living Theatre too, and George was part of this, he was part of the Living Theatre—was break through the Arthur Miller play, the well-made, realistic, maybe socially conscious—Miller’s a big sexist, but otherwise socially conscious—play and free the actor to become a poetic actor. And I think that, and the focus on transformation, the idea of transformation, those two things were key, I think, in what the Open Theater accomplished. The actor didn’t have to drink coffee and mince around the stage. The actor could become a bird. The actor could become anything, and in the becoming anything the actor could show the possibility of transformation, of change. If we can become anything, we can become anything, in all meanings of that word. We’re not stuck in our daily lives. Our world is much larger than that. Our imagination is much larger than that.

So from then, we agreed that the poetic theatre was the way to go, and he then went and started directing Beckett and Chekhov, the poets of the theatre. He didn’t really concentrate on new work, but I think Sam was the one he did concentrate on, but he joined a bunch of people. Irene Fornés was being produced by George. I was writing plays—and I’m leaving out everybody else, but I don’t intend to—But there was a whole burst of poetic work and poetic acting that was released. And George didn’t join the Open Theater. He was in the Living Theatre in The Brig, and he didn’t want to join the Open Theater because George always was focused on language. George was the person who combined, and maybe Joe too, until he became aphasia, the physical actor with the language actor, that’s the poetic actor.

The poetic actor has— George was trained in England at RADA and the Guildhall. He was trained on Shakespeare. Before that, he’d been trained at Erwin Piscator’s Children’s School, which was epic theatre and political theatre. And before that—his parents were dancers—he’d been trained as a dancer. So he combined all of this, plus a great intellect and a great knowledge of language and love of language. So he was the perfect match for me. George, not Joe, not Judith and Julian, who were friends of ours and inspirations, but not the perfect match.

You know, I do think the idea of transformation, which we were all involved in, and that had to do also with taking acid and psychedelics, which are now back in the news in a controlled substance way… The notion that we didn’t have to destroy Vietnam, it wasn’t destiny. There could be another way. It could be another way. And that other way was what we all looked for in our work. And still hold—

Jeffrey: I really love what you had to say about how it was a release, the burst of the poetic actor, the before. You’re the only other person I’ve talked to about the actor-poet in a while. The last time I talked to somebody about the actor-poet was my first interview with Michael Fields from Commedia Dell’arte International. It makes me feel… I’m feeling some sort of way about hearing that again.

I’m a selfish writer who likes to, as I said to Joe way back when, control the structure and the content because that’s what playwriting is. It’s a world vision, it’s a worldview.

Karen: They’re completely different traditions. Completely, because the poetic actor, the language actor, which George was, and Joe was also, although he annihilated plot and character… The Open Theater got rid of the linear, well-made play in order to put the poet-actor, Paul’s bird, the way that you could become anything. And that came out of Viola Spolin theatre games.

Jeffrey: So those plays in the book, they had been written, they had been cataloged, they had been written. And then so you assembled them and edited them for the book. So—

Karen: I didn’t edit them. The playwrights gave me the text.

Jeffrey: Got it.

Karen: Yeah. They had all been performed. So those were…

Jeffrey: Got it. So they existed. I want to pivot to Theater Three Collective.

Karen: Collaborative.

Jeffrey: Collaborative, collaborative. I wrote it down wrong. I’m so sorry. What a shame.

Karen: Everybody makes that mistake. And it’s a crucial mistake because we’re not a collective. We were not a collective. We didn’t pretend to be a collective or, you know, like the Open Theater and the Living Theatre pretended that everybody had equal say, but that was a total lie. Judith and Julian controlled the Living Theatre and Joe controlled the Open Theater. You know, it was not true that everybody had equal say. What we said when we named our theatre “collaborative” was that each artist who works with us will have control over their own work, and it will be part of a whole. So we worked for thirty years with the same costume designer and the same lighting designer. In thirty years, if I had more than two hours of conversation with them about how to design for my plays, that was probably a lot.

I gave them the script. They did their work, they came to rehearsal. They knew what we were doing, and they did their thing. And that was true of everyone. We wanted artists to be in control of their work. And George and I… I wrote the plays, George never told me what to write about. We never discussed what my new play— I mean, we discussed what I was writing about, but it didn’t come from him telling me what to write about. It came from me being moved to write about X and then telling him, and also being inspired by what he could do, which was virtually everything and anything, creating roles for him, but also for Kathy Chalfant and Najla Said and all the other people we worked with. In those cases, specifically writing for the actor. I wrote three roles in Prophecy specifically for Najla using a lot of what I knew about her and what she could do.

I wrote Blue Valiant for Kathy. She was also in Prophecy. I hadn’t written it for her, but she finally did one of the big productions of it. But Blue Valiant I wrote specifically for Kathy. And George I wrote for all the time, specifically Uncle and Extreme Whether, the collaboration which we worked on for years, which was so important to him personally because he was a Holocaust survivor. So anyway, what we meant by “collaborative” is that you have control over your art and it becomes, then, part of a larger whole, a larger experience. And so we worked with people who thought and felt very much as we thought and felt about the world. And we didn’t really talk that much about it, in a funny way. We just were in it together. So it’s very different than people coming into the room and saying, “What should we make a play about?” “Oh, I want to make about this.” “Oh, you write that.” And that’s a very different process. It’s not my process.

I’m a selfish writer who likes to, as I said to Joe way back when, control the structure and the content because that’s what playwriting is. It’s a world vision, it’s a worldview. So people who worked with us found their way, their worldview and our worldview meshed. Our photographer, Beatriz Schiller, who again for thirty years took photos of every play we did, virtually. And she’s a fantastic... She photographs the Met, Robert Wilson, Lee Breuer, and us, among other things. She’s a fantastic photographer. She just got the work. Totally got it, emotionally, intellectually. And that was true of Christen Clifford, the other actors we worked with over time, both got the work and what we were after—eco-feminist, pacifist, whatever you want to call it, another way of being, another way of—

I was talking to Christen and Yana Landowne, they were both students mine at NYU, but they both worked with us in various capacities. And they came over the other day to take me to lunch and Yana said, “Yeah, you taught me that love could be as dramatic as violence, that nonviolence could be as dramatic as violence, and that we didn’t have to, any longer, do violence on the stage. That was not the most dramatic thing. Birth is as dramatic as death and as heroic. The hero risks his life to kill somebody else. And the birther risks her, usually, not always, her life to bring a new life into the world.” And that became a metaphor so that, in one of my last plays that George was in, the men breastfeed and they have an intellectual conversation while they’re breastfeeding their newbies, who are these new creations who will be better than we, other than we, because their heads and their hearts are connected. That was the genetic engineering that they did, connected the head to the heart.

So they couldn’t do anything unless the heart agreed with it. They were no longer separate. And the men learned how to breastfeed. And while they’re breastfeeding, they have an intellectual conversation, which many women have done, standing in a circle, breastfeeding their babies and talking about abolition or other things that women who breastfed regularly talked about. So this understanding of transformation in all these ways is what we collaborated about. People brought their understandings. When George had to turn into an owl in Other Than We, Sally Ann had to figure out how to make that happen in full view of the audience so that he transformed into an owl and no one knew how, but it happened right in front of them. That’s the kind of collaboration that we were after. And I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t tell her how to do that. But she could figure it out. And she wanted to figure it out. It wasn’t for hire.

Jeffrey: I’d love to transition here and talk a little bit more about George Bartenieff and he being a huge figure in the avant-garde and, as you mentioned, and his relationship to New City, and so much of his legacy was shared in the La MaMa Coffee House Chronicles, which I encourage all of our listeners to go check out. It’s a fantastic display of the work of George Bartenieff and life and legacy. So for folks who haven’t seen that or gotten to experience that YouTube video or that collection, I’m wondering if there’s any kernels that you wish that immediately our listeners might know right off the bat.

Karen: We know up on YouTube is Blue Valiant, which is George’s last live stage performance with Kathy Chalfant. It’s filmed with four cameras. It was edited, so it’s a film of a play. It’s not a Zoom of a play. It’s natural film.

Jeffrey: And it’s absolutely beautiful. It’s absolutely striking, amazing, and I love all the details in it. I love the natural details of outside and the representation of the horse in all facets.

Karen: Thank you. I think it should be seen by everyone. It’s there, it’s free, it’s out there. And it’s really a good example of our work in every aspect. And it was George’s last stage performance, and we knew that at the time, of course. But he’s magnificent in it. I didn’t write Sam for him. I wrote Hannah for Kathy, but he fell in love with the character and he was absolutely superb. Yes, so thank you. I’m glad you saw it, and I think everybody should see it, and everybody should see the memorial too, because that was pretty amazing. But everyone should see Blue Valiant if they’re interested in our work. And it’s out there. What I realized— I’m hoping to write a book. I’m writing a book about being a cancer caretaker, but really about being a cancer caretaker of two extraordinary men, Julian Beck and George Bartenieff. And another extraordinary, although very troubled man, my father who died very young of cancer. But it’s partly theatre history and it’s partly cancer history in the writing of this book, which is what I’m doing now since George died, and I actually started it before he died.

And in doing the book I wrote for him, but in doing the book and doing the memorial, I began to think about: Why was this man such an extraordinary actor? What was he doing? In a way I knew it, but I hadn’t put it into words ever before, if I can put it into words. Much of it came out in the memorial, but his combination of physical acting and his love of language, his magnificent voice. He had an absolutely resonant, extraordinary voice and an extraordinary body that could shape change.

So one of the first plays we did together was Better People, it was second play we did— He turned into animals in many of my plays. In Us, which Judith Malina directed, which was the first play we did—beautiful with George—he became a horse on stage and other various things. In Better People he improvised the whole end of that play by becoming a series of animals from praying mantis, which was a very important animal to him, and to tiger. He went through the whole, sort of, animal world and then settled down in front of this big puppet that was made by Basil Twist, one of Basil’s first major New York puppets. And my daughter, who was dressed as... The puppet was a yak and my eight-year old my was with a human face, but horns and fur. And then George as the geneticist-turned-ecologist, and he danced with the beast, and the beast opened up and they played a scene in the belly of the beast and all kinds of wild things happened.

So he was an extraordinary person. He was, by everybody’s account— We used to have a joke that, or it was my joke: “Everybody loves you and hates me.” He was one of the most lovely, open-minded, never held a grudge. He was just a lovely person. But he had these amazing talents, the body that could do anything and the voice that could do anything, and the mind that understood, grasped complex ideas. And he had also no ego. He was not an actor in that sense. He encouraged people and everybody who acted with him said they became a better actor because of being on stage with him, because of his quality of listening, the way he would attend to them on the stage. And so in our theatre, we worked with actors of all— untrained actors, we worked with an Iraqi refugee— Abbas Noori Abbood—who’s a very dear friend of ours now, became a very dear friend.

We worked with other people who had minimal training, and we worked with people who had a lot of training. But George brought them all into an ensemble. He was the ensemble builder because of the way he listened and attended, really by example and by attention and by the things he would say to people. He taught at HB [Studio]. He has a whole slew of students who were mentored by him, including people like Paul Price, who then went to Yale and now has a very marvelous career as a theatre creator to, I mean many, many people. George was an incredible teacher and an incredibly generous, and an incredibly brilliant, performer. And you put all of those things together and you get somebody who just gives an enormous amount to everyone on stage with him, and that’s what he did.

We [Theater Three Collaborative] were never sustainable. We were always totally on the margins, and we sustained ourself through love.

Jeffrey: Can you talk about how Theater Three Collaborative has been able to sustain itself financially and socially and still love each other at the end of the day, at thirty years.

Karen: Never sustained itself financially. We’ve put a lot of money into it, ended up with no money. It never sustained itself financially. We occasionally got grants, but very rarely. We were never sustainable. We were always totally on the margins, and we sustained ourself through love. That’s it. I loved him. He loved me, and everybody who worked with us loved the work and each other, pretty much. There were falling outs, there were ugly things that happened. The people who stuck with us, stuck with us out of love of the work and one another. And the vision sustained us. And again, the vision of another way, the vision of another way, not the violence. The vision of healing, a vision of bearing witness, a vision of taking people in, not pushing people away, calling them in, not calling them out. And we dealt with all the issues of the time and usually before they became issues of the time. But that’s what sustained us, the vision. The vision sustained us and our commitment to each other. And I think that George’s magnetism attracted people, the plays attracted people.

Jeffrey: So much of what you mentioned before led up to the avant-garde and leading up to your and George’s work. And so I’m wondering: How do you hope that this work will carry forward? The work that you did, the work that you continue to do, how do you hope it carries forward into the future?

Karen: Well, I would like people to read the plays and teach them. That’s what I would like. And as somebody has said—a theatre professor—if people teach Extreme Whether, you also learn all the climate science. So in a painless way, you learn the history of the climate scientist, but you learn the climate science because that play is based on climate science and the story of the climate scientists. And James Hansen, who’s one of the inspirations for the play, read the play to vet it for the science. And he is one of the major climate scientists in the world, and he found no scientific mistakes whatsoever. So the science is there, but it’s in story. It’s in a human story. So the history, there’s a lot of history in the plays, that’s there, that’s correct. The US torture program in Another Life is documented, and that’s a play I really love and a play that we never let it be reviewed because we didn’t think the critics would get it.

But the torture community and the ACLU people and the Center for Constitutional Rights people and everybody who was trying to close Guantanamo Bay got it and they loved it. And it’s a play, it’s surreal, it’s funny, and chilling. There’s a whole video of it up on our website. You can watch it. You don’t even have to read it. But the four plays that are published in Plays in Time with photos, with Beatriz’s photos of productions. And then Other Than We and Blue Valiant are published by this wonderful small theatre publisher, Laertes, which— I’m the only American they published, it’s mainly Southern European writers, wonderful writers. So the plays are published. I think all the plays we did are published in some place or another. And then we have a lot of information on our website. We have photographs, we have videos, we have clips of George acting, clips of other people acting. Equity got in the way of having full productions. But we have two full productions: we have Blue Valiant and Another Life in full videos, shot well, good camera work. And we have interviews with Noam Chomsky and Jim Hansen, people who did talkbacks, because we had a lot of important people who spoke about the plays. Not all of them have been captured on video, but many of them have. So our website is full of archival history of what we did, and what people said about it in very interesting ways. So I would hope that the work lives to inspire other work and other people. And also just to be enjoyed.

Jeffrey: Your work on the social-justice front is so driving. What hurdles is social justice theatre facing?

Karen: If you get a bad review, that takes away your chances of money. So censorship is how we were controlled. Of course, there’s no censorship in this country, but there’s lots of censorship in this country. So if you don’t toe the party line, you’re badly reviewed and you’re badly funded. But that’s what’s going on. Now there’s a lot of lip service paid to inclusivity, but inclusivity about what? There’s still plenty of topics… You can have a very inclusive cast and crew, but it’s the content that you can’t— So my newest play, it will be an international collaboration between a Greek theatre company and what’s left with Theater Three, and it will have George. George did the talking fish on tape, so he will be in it. It’s called Troy Too, and it’s about Black Lives Matter, COVID, and climate change. And it has a lot of found language in it.

And some of that found language that I took from the Black Lives Matter marches that I was part of is very incendiary towards the police. It was what people were chanting on the streets. The connecting theme through it all, other than the Trojan women and grief and mourning and memorialization, is “I can’t breathe.” COVID, climate change, George Floyd, and others, and it will be multimedia and made between Greece and America, is still not going to be acceptable in many ways to the powers that be. We’ve been very lucky that we’ve had people who have written wonderfully about our work—Marvin Carlson, Cindy Rosenthal, Andrew Solomon, others—and people who have loved our work who haven’t written about it. Chris Hedges has written wonderfully about our work too. But we have been heavily censored in the daily press. You have to read the work for yourself.

Jeffrey: What you’re identifying here as a hurdle is certainly what we need to do as a people is take action ourselves and find ways to do the work and pay attention to ourselves and really call for action ourselves. And anything else that you want to say that I didn’t give you a chance to stay out loud today?

Karen: Thank you. Thank you. No, I don’t know. I mean, we’re in a crisis, all hands on deck. It’s very important. The most important— One thing about George I do want to say, when he was at Theater for the New City, he wasn’t able to act because he was running the theatre with Crystal [Field], but he was attracting all the best... The first gay theatres, the Indigenous theatres, women. He knew the importance of women playwrights. He produced seven plays of Irene Fornés, Rochelle Owens, and so many other women. The place was a hotbed of what was happening then. And he’d also produced eco festivals in the nineties, anti-war festivals whenever there was a war.

So then when we met, he could go back to acting, which he wanted to do, that’s what he wanted to do. And he did get to act the last thirty-five years of his life when we were together almost exclusively. He wasn’t running a building anymore, but he made this magnet for other artists who are grateful to him—and should be and are‚ and I am grateful to him too—that he just understood who was on the cutting edge, and he attracted them and he was generous to them with time, with effort, with money, with everything he had. And so Theater for the New City in those days was... Mabou Mines, everybody was there. Everybody came out of Theater for the New City, and that was George. That was George, his instinct and his openness and his embrace, and then I am so lucky that I got to work with him for all those years.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Thank you so much. Thank you for sharing so much about him and about yourself and about George’s legacy and bringing it to all of our attention and just giving us some context for all these things. It really does mean a great deal for me to be able to sit with you and have this conversation. And so I am grateful and thank you. Thank you.

Karen: Thank you. My pleasure.

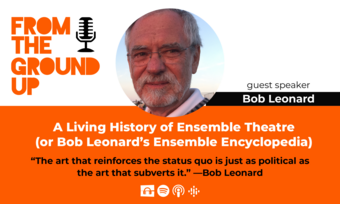

Jeffrey: The level of weaving necessary to demonstrate the life in a theatre is so intense, isn’t it? I knew that by talking with her, we were leaning into a very vital touchpoint in the history of American theatremaking. I meant what I said that Blue Valiant was a great piece of theatre, and I do hope you’ll check it out. I’ll put the link in the show page for you, or you can search for it on YouTube. Also, a quick note to say we hear about Viola Spolin again. We caught this with Bob Leonard in episode three of season three, and here she talks about the exercises she put forth that have evolved so significantly. I often catch practitioners saying, “I don’t know where this exercise comes from.” I would put money on it that it’s a Spolin practice, right.

Before I let you go, let me say that our next couple episodes were focused on written content. We’ve got a contributor to the Black Acting Methods book, Cristal Chanelle Truscott with her SoulWork process, and our next conversation, which is with Mallory Catlett and Aaron Landsman, writers of The City We Make Together: City Council Meeting’s Primer for Participation. If you or someone loves participatory or immersive theatre practices, this will be a great conversation for you to listen in on.

All right, no lightning round this time. I am so sorry. I guess that’s why I ended up having some audio issues. Lesson learned, y’all. Okay. I’ll just say thanks for listening, and we’ll catch you next time on From the Ground Up.

This has been another episode of From the Ground Up. You can find, like, and follow this podcast at @ftgu_pod, or me, Jeffrey Mosser @ensemble_ethnographer on Instagram, and @KineticMimetic on Twitter. Think you or someone you know ought to be on the show? Send us an email at [email protected]. We also accept fan mail and requests. Access to all of our past episodes can be found on my website, jeffreymosser.com as well as howlround.com. The audio bed was created by Kiran Vedula. You can find him on SoundCloud, Bandcamp, and flutesatdawn.org.

This podcast is produced as a contribution to the HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this series and other HowlRound podcasts in our feed on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Simplecast, and wherever you find your podcasts. Be sure to search “HowlRound Theatre Commons podcasts” and subscribe to receive new episodes. If you love this podcast, post a rating and write a review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can find a transcript for the episode along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content on howlround.com.

Have an idea for an exciting podcast, essay, or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to the commons.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here