July 2020, 1500-1800 Hours, Eastern Standard Time

From inside their homes, community centers, and theatres in thirteen countries around the world, ninety-four people “travelled” to the same spot by way of the internet to talk about Caribbean popular theatre for three hours. We carried two languages (Spanish and English) and lots of political, cultural, and economic “baggage” with us—vast differences in identity, worldview, power, and access. We even named our work differently: “popular theatre” in the Caribbean versus “theatre for social change” or “community-based arts” in the United States. But we shared something as well: a deep belief in theatre that speaks directly to ordinary people in their own languages and deals with social issues relevant to them. As it turned out, that was enough to set us on a path together.

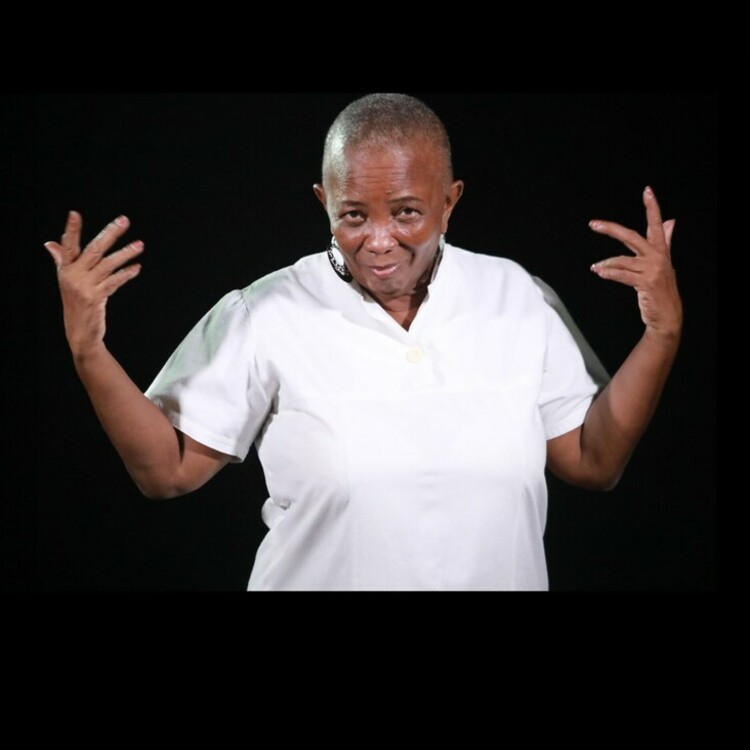

We—Fátima and Mat, the two primary co-authors of this article—are the two very different people who started this international networking project. Fátima is an Afro-Cuban, Spanish-only, cisgender seventy-year-old female actress, director, playwright and the founding director of Grupo de Estudio Teatral Macubá, one of the leading popular theatre companies in the Caribbean; Mat is a European American, English-only, Jewish cisgender sixty-year-old male theatre artist and educator based in New Orleans and the co-author of Beginners Guide to Community-Based Arts. The third corner of the founding triangle was Ariana Hall and Tomás Montoya of CubaNOLA Arts Collective, a small but mighty organization based in New Orleans that connects people, artists, and communities through art. CubaNOLA brought us together, provided many hours of translation and organizational support, and ultimately became producer of the founding event.

Theatre and Social Change Movements in the Caribbean vs. the United States

Unlike in the United States, where theatre for social change is generally considered to be an invention of the twentieth century, there are centuries-old traditions in the Caribbean, both sacred and secular, of artists taking to the streets and the theatres to celebrate their beliefs, resist oppression, and support popular movements by telling stories that reflected the daily lives, traditions, languages, and issues experienced by the masses. In Cuban revolutionary history, theatres were closed during the first war of independence (1868–1878) because Bufo theatre—a broadly farcical improvisational style similar to commedia dell’arte in Italy and minstrel shows in the United States that traced its antecedents back to the public squares of the 1600s when Cuban slaves and freed Black people would make fun of their masters—triggered anti-Spain sentiment and Cuban nationalism.

However, despite extensive bodies of literature, analysis, and continued new works associated with these traditions, popular theatre and the people who still practice it are not recognized for their immense contribution to the culture within academia or cultural institutions of the Caribbean. Fátima and her company, Teatro Macubá, have labored tirelessly over the past forty years to produce one of the only annual popular theatre conferences that exists—Directions in Caribbean Theatre during Festival del Caribe every July in Santiago de Cuba—that brings together about a hundred popular theatre workers from throughout the region.

In the United States, theatre for social change has been a visible national phenomenon only since the 1930s with the Works Progress Administration and only since the 1960s and 1970s did it hit its stride with the work of companies like San Francisco Mime Troupe, Teatro Campesino, Roadside Theater, Living Theatre, and Free Southern Theater. Over these past fifty years, exponential growth in the numbers of local, regional, and national organizations, dissertations, degree programs, plays, books, awards, documentaries, festivals, and projects related to theatre and social change tell a story that is fundamentally different than for their Caribbean counterparts. Today’s Hamilton, the most successful piece of musical theatre in American history, is a direct product of this cultural phenomenon (and, interestingly, the Caribbean popular theatre tradition as well).

As a methodological framework, Sankofa gave everyone their own space of expertise, as well as a collective space where we could reiteratively compare, contrast, and ultimately synthesize a higher level of understanding only by coming together.

And yet cultural phenomena peak and disappear in the United States like clockwork. Many Americans doing this kind of theatre today know that without deeper and more economic, political, and cultural support, it will not become a tradition.

We realized there was a great potential for reciprocity here. Caribbean theatre practitioners need more access to technology, more institutional recognition, and more contact with one another to build a stronger future for themselves and their work, while Americans need a more global understanding of the field and its many histories in order to build a stronger future for themselves and their work. We shared an interest in opening up and strengthening channels for communication, support, and knowledge within and beyond the Caribbean. As Fátima put it: “Sometimes the gaze of the outsider can help us reflect back our own unity to ourselves.”

With CubaNOLA’s help, we decided to collaborate on something small and doable: produce a one-time, one-hour, international online session as part of Fátima and Macubá’s popular theatre workshop Directions in Caribbean Theatre in July 2020. Sure, doable.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here