Millions of dollars are being poured into the “immersive” art sector worldwide in the form of explorable art installations, pop-up projection palaces, virtual reality experiences, and more. As a playwright who has worked in this sector during its ascendance, I’ve been inspired by the vastness of the audience it’s unlocked—as well as that audience’s willingness to engage with deep, complex stories.

I’ve also noticed that many of these experiences can use precisely what we’re so good at as theatremakers: an understanding of how audiences build meaning from a living event and the channeling of precise experiential goals through written text. These insights inspire me to advocate for a text-centered, tech-positive approach to creating participatory performance. I want us theatremakers to bring our craft and collaborative instincts to create discipline-blurring, audience-centered work that is authored.

The great news is, there are works that are already doing this. Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me brings the audience into a debate session and even brings one member onstage to make an important decision. Underground Railroad Game by Jennifer Kidwell, Scott R. Shepard, and Lightning Rod Special, calls on audiences to use toy figurines planted beneath their seats to identify with one of the two Civil War armies. Aleshea Harris’s What to Send Up When It Goes Down begins with a powerful ritual that calls upon every audience member to stand, speak, and physically situate themselves in relationship to anti-Blackness and racist violence. Even when not specifically interacting with the performance, these plays activate the audience’s awareness of themselves and their role in the proceedings… an activation that is very much in an immersive-theatre mold.

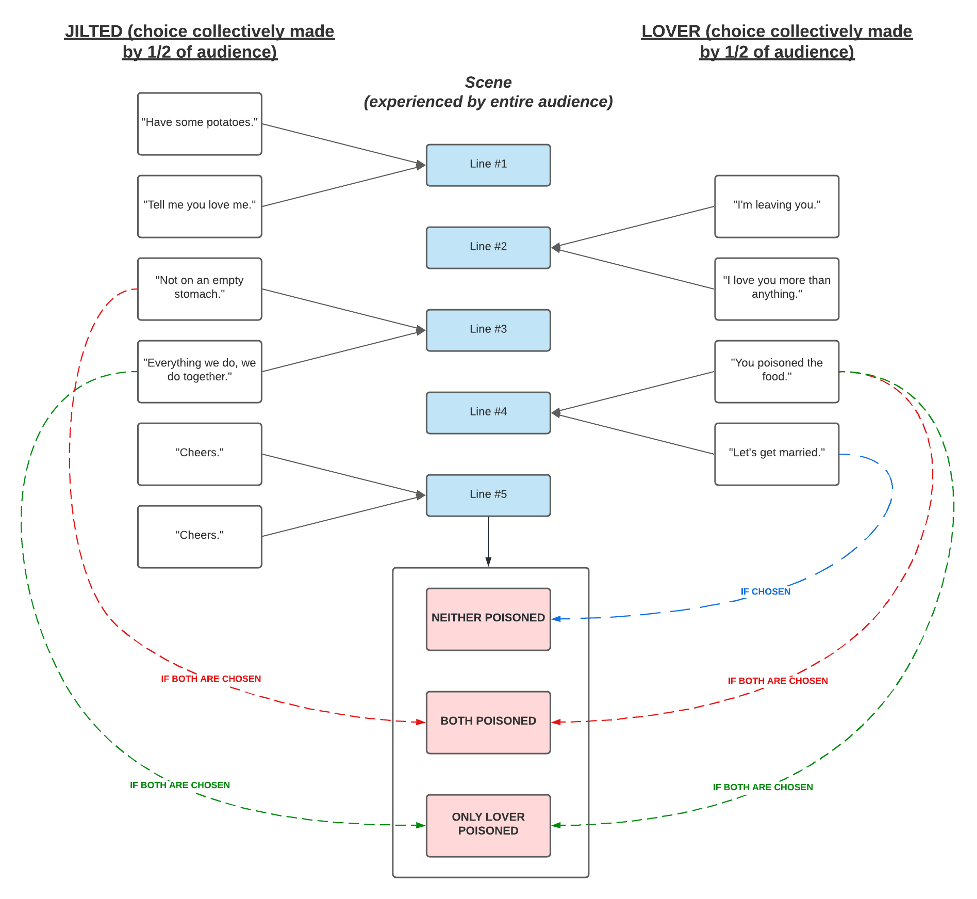

But these plays aren’t really “immersive,” right? They exist somewhere in the boundary-lands between the two forms. Those boundary-lands are what I wish to explore—and, through doing so, advocate for a more precise awareness of how we treat interactivity as theatremakers. It could start with creating a way to label aspects of a theatre piece that call on audiences to influence, co-create, or otherwise activate their physical presence. I call these parts of a play, “playable.”

Playing with a thing brings one into the world of the games it allows; something playable is something open to input and manipulation. All plays (in the suspension-of-disbelief sense) aim to bring viewers into their worlds, but a playable one also offers this sense of pliability—inviting its audience to act upon or within the imagined “container” of a theatrical event. Any play can theoretically be playable at any moment—in the same way that any play can theoretically have a dinosaur enter at any moment. And just as a light cue can be timed anywhere from a mega-slow fade to an abrupt blackout, I propose that the “playability” of a play exists on a spectrum ranging from casting the audience as fourth-walled observers, to full-fledged co-creators.

Here’s a tiny little theatre-nugget:

(Jilted and Lover are eating dinner.)

Jilted: This wine is delicious. Have some food!

Lover: I’m leaving you.

Jilted: Not until you try the potatoes!

Lover: There’s poison in them.

Jilted: Poison? You already drank it.

(Lover dies. End.)

Not a modern classic here, but it’ll do for the sake of an example. Now, as it is, the audience is in a sort of default state: unmentioned, and thus purely witness to the action. A tick forward on the playability spectrum, toward co-creation, might look like:

(The audience is seated at tables with silverware, empty plates, and cups filled with wine. When the play starts, Jilted and Lover are eating dinner at a table with the same set-up.)

Jilted: This wine is delicious. Have some food!

Lover: I’m leaving you.

Jilted: Not until you try the potatoes!

Lover: There’s poison in them.

Jilted: Poison? You already drank it.

(Lover dies. Jilted looks out toward the audience. End.)

Here we use scenography to bring the audience emotionally closer to the action, perhaps inspiring them to reflect on their pre-show wine consumption. This sort of “including but not influencing” approach is echoed in pieces like: playwright Hannah Kenah’s Now Now Oh Now (with Austin’s Rude Mechs), in which audience members interact with dinner place-settings in sync with a natural history lecture; Alison S.M. Kobayashi’s Say Something Bunny!, in which audiences are “cast” in a script reading but are only asked to identify with their characters, not speak their lines aloud; and two recent Broadway hits, Daniel Fish’s revival of Oklahoma! and Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812, which took the time-tested heart-via-the-stomach approach by doling out (respectively) chili and pierogies.

All plays (in the suspension-of-disbelief sense) aim to bring viewers into their worlds, but a playable one also offers this sense of pliability—inviting its audience to act upon or within the imagined “container” of a theatrical event.

Let’s take another step down the spectrum:

(Before the show starts, a blue meter labeled WINE BOTTLES KILLED is projected on stage. The meter fills up in accordance with how much wine the audience has drunk out of the theatre’s concession stands. At the meter’s halfway point is a hatch mark, which—if passed—changes the meter’s color from blue to red. The meter disappears when the lights come up. Jilted and Lover are eating dinner.)

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here