Politics, Propaganda, and Aesthetics

Sorting through Building the Wall

In Building the Wall, playwright Robert Schenkkan imagines an America in 2019 where a nuclear attack on Times Square by terrorists—or perhaps by the Trump Administration pretending to be terrorists—leads to martial law, restrictions on the press, the suspension of civil liberties and the rounding up of millions of immigrants.

We learn this about half-way through this ninety-minute play, set entirely in a prison visiting room, where Gloria, an African-American historian, interviews Rick, an inmate in an orange prison jumpsuit. We know from the get-go that Rick has committed a crime for which he may get the death penalty. We eventually learn that he was in charge of a private prison inundated by the newly incarcerated immigrants. The playwright doesn’t reveal what Rick did until near the end.

It is an anti-Trump play meant to help rally the resistance to what Schenkkan calls Trump’s ‘authoritarian playbook.’

What should be clear before the play even begins—before we walk into the theatre—is the purpose of Schenkkan’s play. As I wrote in my review, it is an anti-Trump play meant to help rally the resistance to what Schenkkan calls Trump’s “authoritarian playbook.” The playwright has told interviewers that he wrote Building the Wall in a “white-hot fury” over a single week after the presidential election, and that he was influenced by Into That Darkness by Gitta Sereny, a 1983 nonfiction book based on interviews with the commandant of Treblinka, the Nazi extermination camp. Schenkkan has described the book as “an attempt to understand the bleakest of the Nazi horrors by focusing on one ordinary man who, for a brief moment, found himself with unlimited power.”

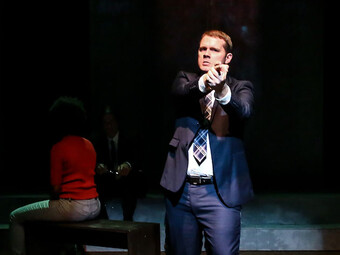

Schenkkan’s purpose seems to have been understood and appreciated as Building the Wall was produced around the country over the past few months, first as a National New Play Network rolling world premiere by Fountain Theatre in California; Curious Theatre Company in Colorado’ Forum Theatre in DC; Borderlands Theater in Arizona; and City Theatre in Florida. But some prominent voices reacted differently when the play opened recently at New York’s New World Stages, in a production directed by Ari Edelson and starring Tamara Tunie and James Badge Dale. And the mixed reviews surely helped end the run of the New York production prematurely. It is closing Sunday, June 4, about a month earlier than the play's intended run.

This brings up all sorts of questions for me, such as:

Are we willing to forgo a fully realized aesthetic experience in exchange for an urgent political one?

Is there a difference between propaganda and political theatre?

Why do we go to the theatre?

Terry Teachout of the Wall Street Journal did not like the play—his view is predictable, given his conservative politics; his vehemence less so: “Politics makes artists stupid,” he wrote, while labeling Building the Wall “the dumbest play I’ve ever reviewed.”

But even Jesse Green in the New York Times dismissed it as “just propaganda—by which I mean that it soothes instead of arouses.”

Are we willing to forgo a fully realized aesthetic experience in exchange for the urgency of now?

This is a definition of propaganda with which I am unacquainted—as are the dictionaries I consulted—but he was not the only New York critic who labeled the play propaganda.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, propaganda comes from the word propagation—as in propagation of the faith—and was first used in the seventeenth century by a committee of Cardinals in the Roman Catholic Church called the “Congregation of the Propaganda.” The OED defines the word as “any association, systematic scheme, or concerted movement for the propagation of a particular doctrine or practice.”

Building the Wall is in its nature, like most theatrical endeavors, “pop up” (using a fashionable phrase). It calls for individuals to gather together temporarily into an audience to have an evanescent experience. Perhaps, in Schenkkan’s effort to encourage many productions of his play throughout the country, it is more “systematic” than most theatre, but, more to the point, I don’t find within it a “particular doctrine.” If anything, it seems meant as a cautionary tale against particular doctrines.

Now, Schenkkan would hardly object to being called a political playwright (although he might object to being called stupid.) He won the Pulitzer for The Kentucky Cycle, a 1993 theatrical marathon that took us through 200 years of the dark side of American history. His most recent play on Broadway, the LBJ biodrama All The Way starring Bryan Cranston, won the Tony Award for best play. Neither are what you would call unopinionated. Perhaps the difference is that the political passion behind those two far more complicated theatrical pieces can be more easily ignored in favor of such criteria as stagecraft, character psychology, aesthetics.

The politics of Building the Wall is more evident, as is a sense of urgency. Should it therefore be judged differently? How, for example, do you react to this passage in the play?

GLORIA: In August 2016 the Justice Department publicly announced they would be phasing out the use of all private prisons.

RICK: But they didn’t, did they?

GLORIA: No, the election changed that. On February 23, 2017, the new Attorney General Sessions announced he was in support of private prisons. Stock prices rose immediately.

I distinctly remember my reaction as: “I didn’t know that. Wow.”

Critic Adam Feldman reacted to that very passage in his review in Time Out New York: “This is not dialogue. This is notes.”

That exchange between Rick and Gloria is just one of many that weaves facts into the play, helping to ground in present-day reality the dystopian speculation that dominates the second half of the play.

It also helps, in my view, that Rick is not the “straw man” that some New York critics have considered him—an invention created to be knocked down. I feel he is given his due as an “ordinary man”—yes, conservative, and a (former) Trump supporter, but given time to explain his views….and allowed to score some points:

RICK: Why is it when conservatives wonder about stuff like this, conspiracies, we’re being paranoid, but when liberals do, they’re being smart?

Schenkkan gives us enough of his background and character so that I at least could take it on face value, when Rick says, “Look, I’m not crazy; it was the situation. There was enormous pressure from the Brass…”—even if Gloria calls it an evasion and threatens to walk out unless he starts getting real.

New York theatregoers who distrust political theatre like Breaking The Wall should brace themselves for more to come, including Moore to come: The Terms of My Surrender, a one-man show by Michael Moore that marks his Broadway debut, begins July 28. A stage adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984, currently in previews, will open on Broadway on June 22. Not long after Donald Trump called the press “the enemy of the American people,” producer David Binder announced he would be bringing Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, to Broadway in the 2017–18 season. American playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins will be adapting a German version, which was originally presented in Berlin.

***

Jonathan Mandell’s NewCrit piece usually appears the first Thursday of each month. See his previous pieces here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I saw the New York production, and was engaged all the way through. It's not often one goes to the theatre without being bombarded by fancy effects, even in non-musical productions. The text of 'Building The Wall' and the simple, straight-ahead presentation cleared space for me to sit quietly and listen in the room. How often are we doing that these days? Mr. Schenkkan wrote his response to the world in real time. He worked quickly, yes, but I don't agree that the text wasn't somehow 'fully realized.' Teachout and his uses of the words "stupid" and "dumbest" in the WSJ review don't even deserve consideration, and given that this is a play about the politics of the very recent past, the present, and a pretty believable near-future, Mr. Feldman's definition in his Time Out New York review of what is "not dialogue" seems short sighted, at best.

I saw Building a Wall in New York. I was held by the initial mystery of why the guy was on death row, as he told his story, I was more and more disgusted by the horrors he recounts and his excuses, but gradually I felt compassion for a man caught between his family's survival needs and his ethics as he slides deeper into concentration camp challenges. For days after, I saw all of us Americans on the streets, including myself, as potential guards at Abu Ghraib, Kandahar and Guantanomo prisons and funders of out-sourced black sites. I understood how each of us, with enough economic stress, could slide into the same systematic, pragmatic reaction to a man-made Dante's Inferno. That's a powerful dramatic arc. It could have been a solo narration, but having us on stage as interviewer, helped us unravel the veins in the blood clots of the play... more crucial than quibbling over how fast the play was written or how politically aligned it is with our current descent.

You make two points:

1. You found the structure of the play -- the initial mystery and slow reveal of Rick's crimes -- dramatically satisfying.

2. The character of Rick is developed such that you found yourself sympathizing with him, and thus all the more aghast at what he did.

I know you are not alone in either reaction -- and both point to Schenkkan's skills as a dramatist.

Just wait a little while. Trump (the Chump) and the rest of the kakistocracy will provide much material for a comedy. And then for a tragedy, if there is still an audience for theatre.

Ooh boy. Hmm... Okay, in the spirit of positive inquiry, let me state how Terry Teachout and Jesse Green give me hope!

It would arguably also be a positive thing (in the sense of Equal Time) for someone to write in a week and produce a companion piece to "Building the Wall" and "The Terms of My Surrender" entitled "Hillary in Hell", in which HRC actually won the recent election, then made good on her promise to implement a no-fly zone over Syria, causing a war with Russia and a nuclear holocaust in which all of humanity is destroyed.

You make an interesting pivot there. If you read the reviews by Terry Teachout and especially Jesse Green, you'll see they do not make political arguments about Schenkkan's play. Their objection to it is on aesthetic grounds -- its lack of drama, etc. I imagine they both would also object to the play you've conjured up.

I'm not sure what the underlying purpose is in your comment. Are you arguing (with vivid indirection) how people who are anti-Trump give such plays as Building the Wall a free ride? Or are you simply using this theater website as an excuse to promote your absurd political views? If the latter, let me go on the record labelling them a prime example of false equivalency. Does anybody truly believe that we would be worse off now abroad if the former Secretary of State had become president?

This play can be produced elsewhere and not be measured by the New York litmus test. I think this article speaks to more out of touch New York theatre is with the people who attend.

What precisely is the New York litmus test?

I'm not completely sure I understand your point.

The litmus test is : "If it isn't accepted in New York, then it won't be accepted anywhere."

Sure, New York is where Broadway and Off-Broadway is, but there is good theatre everywhere. There are audiences who are different from New York audiences. I hope this helps. Reading this article makes me think how great this play might be in Cleveland, Ohio.

Ok, yes, good point.

I wonder what explains the discrepancy for this particular play. Could it be?

1. New York audiences are less open to explicitly political plays. (This doesn't seem likely.)

2. New York audiences are less tolerant of plays where the aesthetics seem of secondary concern, no matter what the subject matter.

3. There was simply too much theater happening at the same time in New York, and Tony excitement, for audiences to engage in this small show.

4. The NY Times reviewer didn't happen to like this show, and thus New York audiences didn't go. Had he liked it, they would have gone.

This fourth explanation gets added weight given the decent reviews the other productions of this play received in such major outlets as the Washington Post and the L.A. Times.

Well, all those explanations carry some weight. But, I don't know. An original play doesn't seem to get much traction as a revival.

Did you seriously just write an article asking if a play needs to be good...or just politically correct?

Howlround, goodbye. You've reached Peak Ideological Purity.

No, I didn't. "Politically correct" is not the same as politically engaging. And "good" is so subjective as to be meaningless. Some people would find a play that informs them about the world to be "good."

The question I was asking (myself as well as the readers) is whether a play whose purpose is urgent political engagement should be judged with less consideration of its aesthetic appeal.

If you've ever seen the Theatre of the Oppressed NYC (http://www.tonyc.nyc/) -- with all due respect to them -- the aesthetics of the experiences they create seem clearly of secondary concern to them. Should we just accept this as a different kind of theater?