Jamie: How did you come to conceive of your specific ideas around what Roma Futurism looks like?

Mihaela: I have always been interested in science fiction, and I wanted to create something science fictional, something nobody would think Roma artists would create.

In 2016 I was part of an exhibition in Bucharest called “The Disappearance of Technology,” which got me thinking about Roma people and their relationship to technology. For me, technology could have been another craft that Roma invented if we had had access to the same resources as white people. My interest in witchcraft was also a result of many things—Roma witches are stigmatized and ridiculed here in Romania.

In Roma culture there are groups, and when we Roma meet it is traditional to ask, “From what kind of group are you?” My group is musicians. I have friends from the flowers group, the blacksmith group, and so on. The Roma witches are one group, the only group named after a woman’s job. I wanted to update witchy language and use witchcraft as a political feminist tool, a powerful tool to fight injustice and heal our historical trauma.

I had a residency in Hong Kong at Para Site Art Centre and traveled to Manila and Taipei researching rituals and magical practices. I met fortunetellers, witches, and shamans. I acquired a collection of practices and rituals that I could explore next to the practice of Roma witches, and I tried to develop a new language.

I really appreciate what these Roma witches are doing. They are politically involved, performing political spells. We—the feminists from Bucharest—have learned a lot from them, and they have also learned a lot about our principles of feminism and anti-capitalism. They even came to meet us at a club on New Year’s Eve to bless the people. They performed rituals for everyone who was in the club and for the future of feminism and the fight against capitalism. It was super powerful, seeing them on the stage.

My vision of Roma Futurism is the intersection of Roma culture, technology, and witchcraft. If another Roma artist wants to adapt it or take it somewhere else, they should. I would love to see Roma Futurism become a bigger movement.

I thought: Why is there no Roma art that talks about the future and how we want to see ourselves in the future as a community?

Jamie: In thinking about creative alternative histories and new futures, can you speak to Roma Futurism’s relationship to Afrofuturism and other futurist movements?

Mihaela: When I was researching in Hong Kong, I looked to Afrofuturism, Sinofuturism, Gulf Futurism—many different types of futurism. But I felt very close to Afrofuturism because I found some similarities between my community’s struggles and Black people’s fight. Futurism becomes an instrument, a tool, in projecting our future. It is really powerful and threatening to those in power who don’t want us having a future in this world.

Futurism asks us to consider and imagine solutions—for the entire world, for the environment, for the climate crisis, for fighting against all the crazy shit happening now with our planet. It’s also about imagining how technology can help us in our fight, because technology is very discriminatory against people and we don’t think about it.

Jamie: What are the implications of creating new work with Roma Futurism as your point of departure? I’m interested to how Roma Futurism has manifested in and impacted your artistic practice.

Mihaela: In the last year, my practice has been impacted a lot by these ideas. I created a performance that was the result of the research from Para Site. After I finished my residency there, I went to Berlin to perform in Medea, as Medea, who is also a witch. I focused on expressing this side of Medea by weaving in elements of the performance I had made at Para Site. With this interpretation of Medea, I cursed European politicians and politicians who are against Roma people. I rewrote the language of the curses, inserting political and technological terms, in order to make them sound more theatrical and, also, to protect myself and take distance from the real witchcraft because I don’t identify as a witch.

A lot of power came from this action because when you have no power, it is appealing to call on the supernatural and the invisible forces. This is why witchcraft is our spirituality—it’s political in some way because these are the only tools that remain us to fight these injustices.

I have performed this “curse” afterwards in different contexts at different art events. Then, last summer, when I was in a playwriting residency at the Royal Court in London, I said: “Okay, now I have time to write the real play about Roma Futurism.”

Jamie: Tell me about the play you developed.

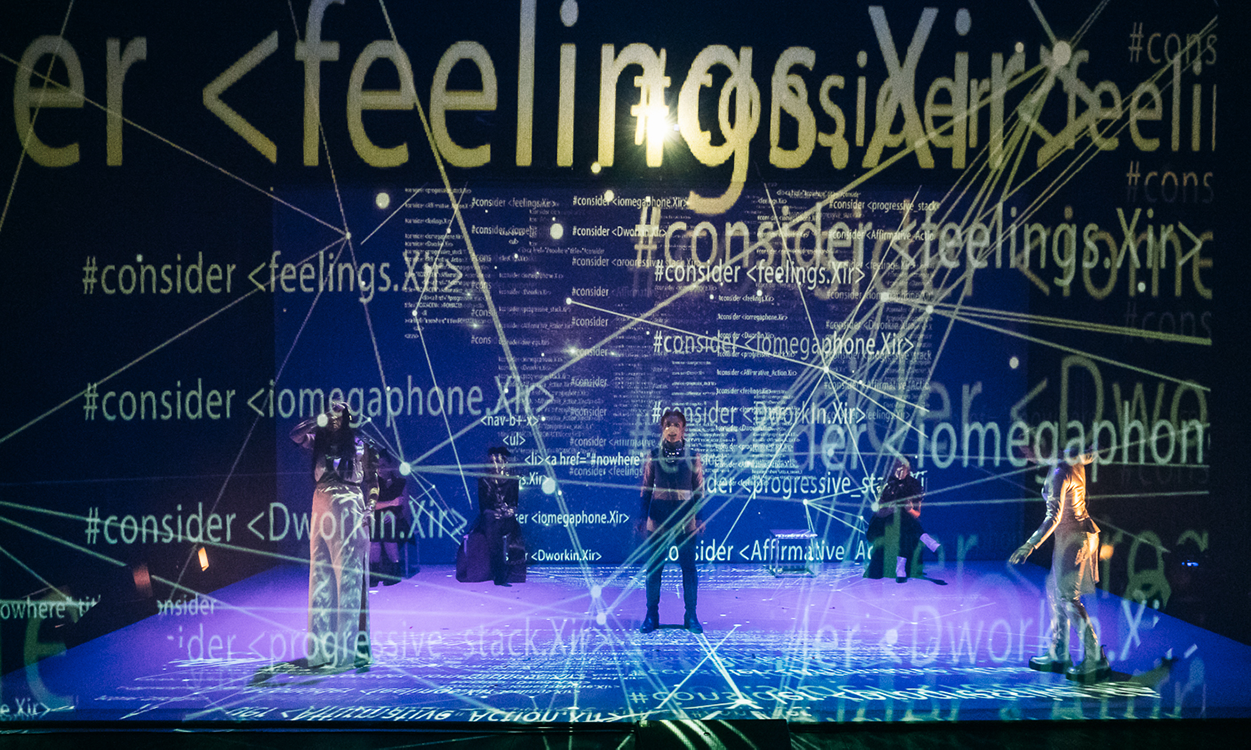

Mihaela: It’s called Romacene: The Age of the Witch. It’s about six Roma women—all except one settled in England—whose ancestors are witches, and they practice techno witchcraft to try to develop new politics in Europe. I created a kind of alternative history. At some point they hex Brexit and hack Boris Johnson, and they steal money from the Brexit party. Eventually they are caught by the police, but meanwhile they have created a virtual reality called the Romacene where they live through their digital avatars. In the Romacene, these Roma women hold the power, they have their own rules and they are working with very futuristic tools—in the show we used holographic projections. Also it’s funny! Because this is how I write. I love comedy so much.

It premiered at Andrei Mureșanu Theatre in Sfîntu Gheorghe, Romania in December 2019. We’ll bring it next to Bucharest, and we want to bring it to Berlin, where I also work and where our director, Tina Turnheim, is from.

Writing the play, I wanted to manifest ways for us to survive, even if it does not end in a positive key, because reality is not positive for us.

Jamie: How did the audience respond to the piece?

Mihaela: I think a lot of people had a more exotic vision about the play when they heard about witchcraft. They didn’t expect it to be this representation of the future. Our costumes were really amazing, super futuristic; no long skirts, no flowers. I think this surprised them a lot. Some white people felt that the story of these six women in the future—controlling it—didn’t have any meaning for them. For me, this is not a play for white people to find themselves in.

Jamie: Both of those reactions show how the play is doing the work—subverting expectation, creating a different kind of imaginary. And it’s making people feel uncomfortable.

Mihaela: Yeah. We also thought on some level it really worked because audiences had this reaction and they had to contend with new ideas and representations. On the other side, there were a lot of Roma who came to see the show, and I think it was very nice for them to see this future. Writing the play, I wanted to manifest ways for us to survive, even if it does not end in a positive key, because reality is not positive for us.

Jamie: You previously shared that the first contemporary Roma theatre production in Romania happened in 2010 with an adaptation of I. L. Caragiale’s A Stormy Night performed in Romanes (the Romani language) by Roma actors. In the last decade, much has happened in the Roma theatre scene, including your founding of the Roma Actors Association, your founding of Giuvlipen, and the creation of new works such as Who killed Szomna Grancsa?, Urban Body, Kali Traš: Black Fear, and Sexodrome.

Just a few years ago, Giuvlipen’s play Kali Traš: Black Fear was the first Roma play ever to be featured in a Romanian state theatre. There have now been multiple editions of Roma Heroes, an international Roma theatre festival, and I just received a copy of RoMA HERoES: Five European Monodramas, the first international Roma drama collection, published by Independent Theater Hungary, which features your play Tell them about me.

Given these developments, and no doubt others, I’m curious about how you see or don’t see the representation of Roma people changing in the theatre sector in Romania and in the culture at large.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here