Robert: Interesting. You were obviously celebrating Shakespeare's remarkable storytelling and poetry while also illuminating his cultural biases and subverting the traditional expectations.

Nicolette: Absolutely. We've always been subverting. So we just decided that we were going to cast Shakespeare in such a way. But the way that we did Macbeth—we didn't have kings, we had prime ministers and we set it not in a physical battlefield, but in a political battlefield. It was set during a Bahamian election where Macbeth is the chairman of his political party and he kills his leader. The witches in our Macbeth were radio talk show hosts. We used Queen, so “Radio Ga Ga” was our opening music.

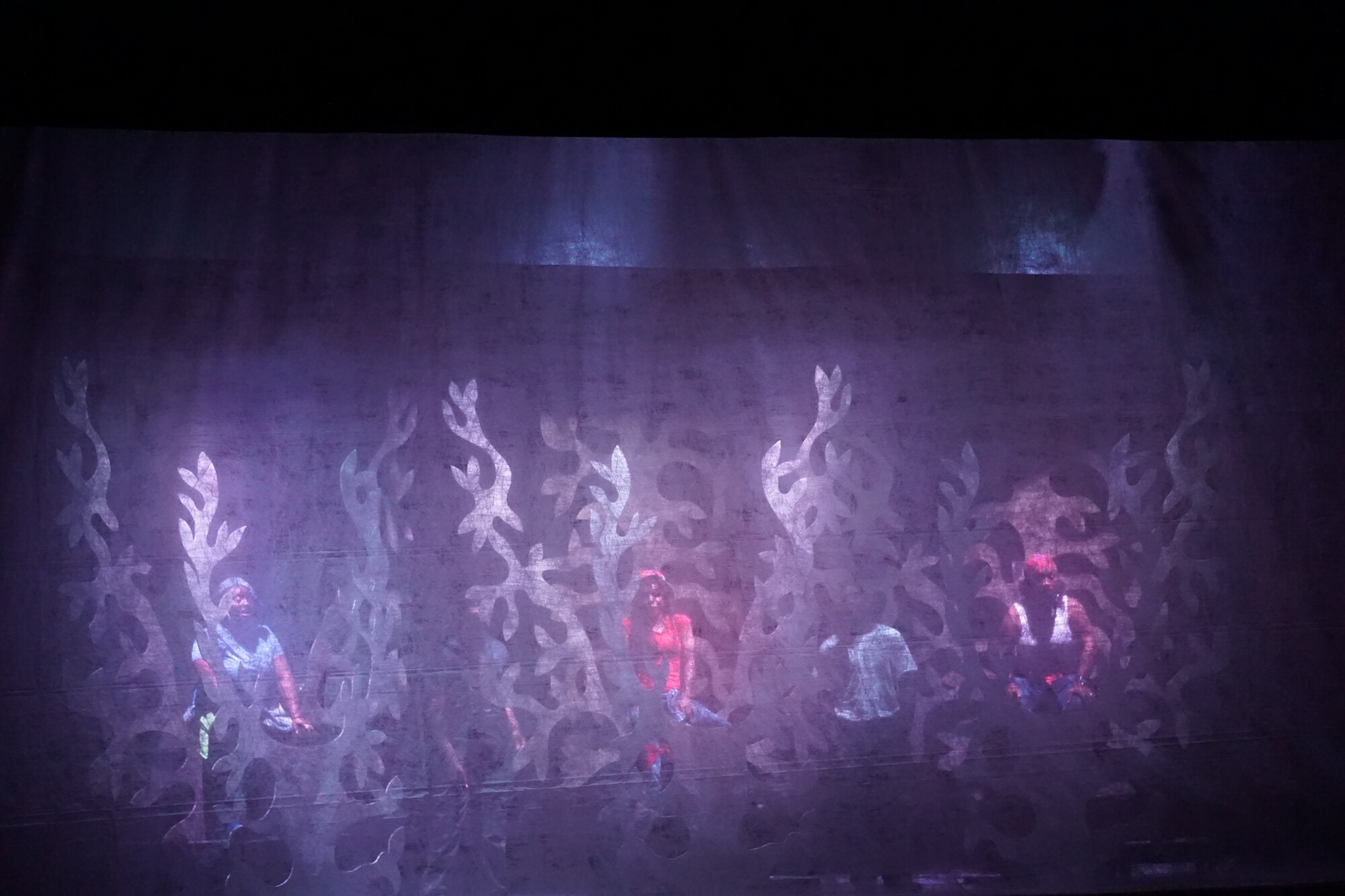

That's the kind of thing we do, but we also don't rewrite the play. We will cut it, select bits and pieces from it, and put a lot of thought into setting. When we did A Midsummer Night's Dream, we set it on one of the Bahamian islands that is known for magic, Cat Island, during midsummer. We changed all the fauna mentioned in the play into local fauna. And we found that it spoke to the people, and we had different reactions every play we did.

For most of the Shakespeare plays that we've done, the biggest audience we have is school children. When we started off, we went through the plays that everybody studied in school. We started with Macbeth because that was the most common one. Then we did The Tempest; then A Midsummer Night's Dream. After that we did Merchant—not The Merchant of Venice. We set The Merchant of Venice in Nassau and called it Merchant. In our production, Shylock ran a numbers house, which was a semi-legal gambling place and a money lender. But the important choice was that Shylock was also Haitian.

Robert: Haitians are often marginalized and viewed as outsiders in the Bahamas?

Nicolette: Yes, and we played on that. Shylock was a despised outsider and it works really well because in the end, Shylock is exiled and sent back. Shakespeare’s Shylock is Venetian, just like everybody else in Venice and in our play, Shylock, the Haitian, is exiled back to Haiti even though he never lived there. That really touched a nerve with some of our audience. I remember one student was totally devastated. He said, “That ain’t right. He grew up here. He never seen Haiti. He don't speak Creole. How could they send him back?” We found that that was powerful.

Robert: A bold choice. It sounds like you make a lot of bold choices.

Nicolette: Yes, we do. We did Julius Caesar, which was probably our most successful Shakespeare because even more Bahamians have studied Julius Caesar than have studied Macbeth—particularly people who went into politics. They were inspired by Julius Caesar to go into politics, and they often quote the play. So the audiences that we had at the nighttime shows were the largest audiences, as opposed to the school shows we had at the matinee. There would be these big political men sitting there in the audience quoting entire speeches. Philip told his actors, “You cannot get this wrong, everybody out there knows these speeches.” That show was, again, political.

Robert: Thanks for touching on your approach to Shakespeare. The festival also includes other plays, which are equally important. How does Shakespeare in Paradise promote and sustain the unique and vibrant traditions of theatre in the Bahamas?

Nicolette: One of the things that we do is design the festival in a way that prevents us from losing any money. In order to do this, we try have the Shakespearean play at one end and a Bahamian play on the other.

Philip: We call them signature productions. A signature Shakespeare production and a signature Bahamian production.

Nicolette: Or local or Caribbean regional…

Philip: That's the way it's been from the beginning. The first year, we did Music of The Bahamas along with The Tempest, so they were the two anchor productions.

Nicolette: And then we also have smaller productions around them.

Philip: Or in between or we have invited performers in between. We've had five shows as our base. But we've had years where we had as many as eight productions and years we have had four productions. Normally there is one major Caribbean, Black American, or Bahamian work that anchors. That's the work all the students come to see.

Nicolette: And in recent years they've tended to be musicals. Obviously, you can't afford a musical every year. But we have had a division…

I think we have a natural Bahamian theatre. It’s the talent pool. The thing that we do as the theatre experts, more than anything else, is focus the innate ability of the actors who walk through the door; what already exists.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here