Development of Malawian Theatre

A Conversation with Maxwell Chiphinga

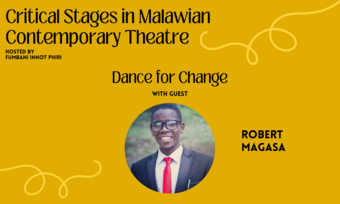

Fumbani Innot Phiri Jr.: Welcome to Critical Stages in Malawian Contemporary Theatre Podcast, produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide, in partnership, Advanc[ing] Arts Forward, a movement, advanced equity, inclusion and justice through the arts by creating the liberated space that uplift, heal, and encourages to change the world. I am your host Fumbani Innot Phiri Jr., a producer, actor, director, playwright, and of course, a freelance journalist.

Critical Stages in Malawian Contemporary Theatre, I interview established theatre artist from all backgrounds to explore the precarious journey of theatre in modern world, defines its problems, and find better solutions to sustain the performing arts in a generation of motion pages. In this podcast, I lead discussions with established performers, directors, writers who are exploring ways to greet these challenges while their works inspired the community.

Today's episode, I'm with the Max DC, Maxwell Chiphinga. And Max Chiphinga is a well-known artist, a theatre artist, a resident of National Theatre [Association] of Malawi, also a director of Emancipation Ensemble Theatre in Malawi. He's a legend again say. Max DC, welcome.

Maxwell Chiphinga: Thank you.

Fumbani: All right. It is our pleasure to have you. In this episode, for the past episode, we have been having some scholars, some academics, and some young theatre artists to discussing issues about Malawian theatre. Basically, we have went through a critical age. Now we would like to explore how these themes or theatre and Malawi has been and how theatre it is. So, first of all, who is Max DC?

Maxwell: Max DC is an artist. I best describe myself as simply an artist. An artist in the sense that there are different, there are quite several facets or dimensions to my artistic life. I'm musician. I'm a playwright, an actor. I direct. I'm a storyteller. So you can see the different kind of aspects.

Fumbani: Yeah. Magic Spring.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: All right.

Maxwell: So I better describe myself as artist, although I know there's one side that I lean much on, which is theatre right now. So I can say fine, because I'm leaning much on the theatrical side at present, I’d better describe myself as a theatre practitioner.

Fumbani: All right. And also, when I was a little boy, I had a chance to watch you on TV station while I was singing music.

Maxwell: I was doing some kind of music at the time. I was much on the music side at the time. So it just depends. There's a season in which I’m much in one area, then the other, but theatre is encompassing. It takes all: takes music, it takes stage acting. So it takes everything. So theatre is good because even storytelling is part of theatre and all these things. So to say I'm a theatre artist, could be much more encompassing simply than simply to just say I'm a musician or I'm just an actor. But theatre practitioner is good enough. So yeah, I've been on TV ever since. Anyway.

Fumbani: Yeah, it has been a journey, A quite journey.

Maxwell: Long journey.

Fumbani: Right. And can you explain your journey in theatre?

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: And basically people can say, “We have few people remaining in industry who witnessed the experience of Golden Age of Theatre in Malawi.”

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Can you just take us back and see how theatre it was in that time?

Maxwell: Yeah. Theatre has evolved. We're talking about theatre in the nineties. That's the theatre that I actually entered. I entered into the theatre industry in the nineties. I think it was 1990, when I joined Wakhumbata Ensemble Theatre.

Fumbani: Wow.

Maxwell: Only professional theatre company in Malawi at the time.

Fumbani: Yeah. Wow.

Maxwell: Which was being, I spearheaded by Du Chisiza Jr., the late, the legendary. So he's the guy that trained us, that taught us. He had an American kind of style, although he… he had a American background in training. But when he came, he tried to blend his own knowledge to create a new theatrical movement, which could be identified with Malawi to say, “this is Malawian theatre.”

Fumbani: Even before he went to America, people knows, Du Chiza as a legend because he produced production very powerful.

Maxwell: Even before he had a production that won at him of those days. It was on number one. It was.

Fumbani: Yeah, I remember that. This is that tag.

Maxwell: Yes. Yes. So you can see, even before he went to America, he was already into the theatre industry. He had that passion. So when we joined a Wakhumbata Ensemble Theatre, we were oriented into that kind of environment. And also the passion was also infused in us to a point where we… okay, fine.

Let me say, theatre in Malawi has been, it was vibrant way, way back in the nineties because some people attributed to several factors. They say, Okay. In the nineties, we did not have a lot of television stations. We did not have a lot of radio stations. So people did not have more entertainment. So theatre was almost part of the entertainment that we could resort to. But I believe apart from that, there was so much love for expressive art for theatre in Malawi.

Fumbani: Yes.

Maxwell: At the time, because the artists themselves were so passionate about the art. So I think the passion in the artists radiated, and it moved and it drew the audience to love theatre just as the artist loved theatre. So it began by being ignored. Like the first productions of Du Chisiza Jr., I remember my first play to watch, it was before I joined Wakhumbata Ensemble Theatre was it used be called Bloody. It was done in 1990, and the audience was so small, but the performance was so powerful. So you can see over the years, because he was so persistent, he did not give up.

Little by little, we began to experience an increase in the audience to a point where now we began to feel auditoriums. But it was quite a journey, and it was so traumatic at some point to see that you're putting in so much passion and people do not seem to be attracted to what you're doing. But eventually it yielded some good results to a point where now theatre was a big thing. We could now compare it to football, because at the time, football drew the crowds. But we were able to fight to a point where now even footballers could know that if there's theatre performance and we also have football nearby, we were going to, we'll balance.

Fumbani: Yeah. Balance. And at that time, we would see, listen to the adverts of the production.

Maxwell: The simply, the adverts was enough to draw you to.

Fumbani: Yeah. I remember basically Gertrude—

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: Because she introduced theatrical with new styles. Cause they're coming in the modern world. Whereby motion pictures were coming out where we could see classic performances. Or we see funders from outside coming out with money. Do some classic adaptations and stuff. So still get, drew some audience.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Comparing with other theatre productions.

Maxwell: Yes. It was like that.

Fumbani: And we call those days, that is donor syndrome days. Whereby we would see the coming of Nanzikambe, the coming up of other theatre groups across Malawi.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And it changes everything. I was little, but when I watched the, adverts from Gertrude Kamkwatira I could imagine. How do, was that by that time?

Maxwell: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. Sure.

Fumbani: So can you take us a bit? By the time in early 2000 where whereby you could see the Western donors coming in Malawi, flocking in Malawi, spending a lot of money, pumping in money to do some productions. Some production whereby where donor directed, not by the artistic classic element. What was the experience like? And I think that time people explore more about theatre.

Maxwell: Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

So that's what I can say much about the coming in of donors and pumping in money into theatrical industry. It was good. It developed an art to a certain level, but it also drained the kind of passion that people had for the art.

Fumbani: But what happened?

Maxwell: Yeah. That era came and actually it was a season in which we witnessed transition. Transition in the sense that initially we used to have theatre, Malawian indignant theatre.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: We self-sponsored actually. Okay. We were not used to being sponsored to do productions. We just knew that we had to find money, and then you do some adverts on the radio, and then you go on TV. You do your promos however you could do them without receiving any donation from your company or from anybody else. Then we came to this season in the 2000 in which now we witnessed the coming in of donors to sponsor productions like Shakespeare plays, so that probably local groups could adapt those plays and do them in a probably Malawian way. But the only thing that I witnessed was that the passion was eroded by that season, because now people were now focused much on donor funding.

Fumbani: Yes.

Maxwell: The artists… I remember the kind of money that we used to receive way back then used to be very small, but we didn't mind because what we simply wanted was to be on stage and do art. That was our main focus. We do not care whether we're going to get money, or we are not going to get money, but the feeling that you have performed, and you know have done something which you love. That was enough to keep us going. Then the coming in of the sponsored productions and all, we began to witness now that it was becoming difficult now for artists to perform voluntarily as we used to do before. They would only perform when they hear that this production has been funded.

Fumbani: Funded. Yeah.

Maxwell: All right. And again, it also kind of drained the local talent in the sense that now people were looking for productions that they could do, which could attract donor funding. You see? Now, the plays that we used to experience in the nineties began to disappear. Now, you could now hear people more talking about, "Oh, we want to do an adaptation of A, B, C, D,”—all this production from the West. It wasn't bad. It was a good thing because in the sense that people were learning a different theatre, but it did not have to kill our own theatre, which was existing and vibrant in the nineties.

So that's what I can say much about the coming in of donors and pumping in money into theatrical industry. It was good. It developed an art to a certain level, but it also drained the kind of passion that people had for the art.

Now, they began to focus much on money. Now, if you wanted to be a production, you were working with a shoestring budget, and you want to do that production, you could hardly get an actor because first of all, they want to be paid. We never knew in our days that you could get money for rehearsals. You understand?

Fumbani: Yes, yes.

Maxwell: But now, the coming in of dollar funding, rehearsals, you get some allowance, and then you are, okay, you do a production, you get a high amount of money. Now, when the Nanzikambe, because this brought came around with Nanzikambe actually.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: When Nanzikambe began to, when their momentum began to go down. We've now begun to experience that art was almost like dying because now there was no more money from donors, which means actors were just seated, waiting for donors to come with money so that they could go on stage. So we began to experience a decline in both passion as well as frequency in performances.

Fumbani: All right. That age drain the creativity. That age even drain the spirit of writing productions—

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Because 70 percent of production could see, You could see adaptation from outside Malawi.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: We could see production from Norway by Ibsen, production from German by Goethe, production from England, Shakespeare. All those production were donor driven. At the same time as the 2000 was going up. Political plays went down.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Because, you could remember how Chancellor College affiliated student to could do more for theatre for developing.

Maxwell: Yeah. Yeah.

Fumbani: Based on donor production.

Maxwell: Yes. That's it.

Fumbani: You see. And even to other artists who came by that time experience, the element of receiving money after production. Experience, as you said—

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Getting money, our allowances from a rehearsal and all that. And then a year whereby donors deserted from the creative industry in Malawi. In 2011, the reason there was political crisis in Malawi. We see the French Embassy going out of the country. We see the Norwegian of the country.

Maxwell: The British Commissioner.

Fumbani: Yes. And is that affected our industry—

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: By that time, and more specifically, we talk about the French, because during the time of Du Chisiza, they used to use French Cultural Center for Production, which is basically, it was for free, and it was a platform for them. And after that, it was disaster. How did you manage to produce productions? Still, crop up around, across Malawi with the French Cultural Center because the space was free for the artist. After that, how did you manage to?

Maxwell: The theatre was tough at the time, and that's the time we mostly focused on doing productions in secondary schools. Theatre in secondary schools was much heightened because of lack of space, theatre space.

Fumbani: All right.

Maxwell: We were, because almost the French Cultural Center was banned. They were politically, they were banned from hosting shows, theatrical shows. So because of that, it was kind of very difficult now, to perform in a place, in a community place, in a community center, where people from different locations could come and watch. So in this season, our survival was through secondary schools.

Fumbani: All right.

Maxwell: This was the time. Now we much going into secondary schools to do productions, and this is the time that we still moved. We managed to move forward because of the speed that we were initiated with. We entered into theatre with passion, not because there is money right. Now there's a group of artists that entered into theatre because they experienced that there was money.

Fumbani: Money. All right.

Maxwell: So there was a difference between these two types of artists. One that entered into theatre through passion, survived even through the most difficult times, because his passion drove him to continue moving and find ways or of moving forward. Now, you could see an artist was attracted into theatre simply because there was donor funding. Most of them, they went out. Now they started looking for jobs. Most of them, even now as we speak, they started jobs and did… They're no longer in the theatre's industry.

It's a new blood now, which is now coming back into theatre at this point in time. But the biggest part of the people or the artists that came in the early 2000, going on to 2010, most of the people that entered into theatre in that time are no longer practicing theatre now. Most of them are working on there they quit performing arts altogether. But what made us survivors, you have asked, is simply the passion. We were driven by passion. You see, when you are driven by passion, you are destined for great and great heights other than when you're driven by the proceeds that you get after doing theatre.

But if you're passionate about theatre, you are likely to survive even in the most difficult times. Actually, that's what theatre is all about. Theatre is about expressing yourself and also your environment. And also the practitioner is almost like a mirror of his society, where whatever he writes. You remember during the Kamuzu days, we used to write plays, but most of them were figurative kind of productions that you didn't say something directly, but the audience could be able to say “What this guy is saying,

it could be…” Most of implications they could imply, but you had to write in a very crafty way that even the censorship board could not get what, they could not ban your play. Because it was not straightforward, like criticizing head of a state or criticizing a particular party in a way that which is happening now, you can, because of freedom of expression, mean, I also feel like freedom of expression has kind of killed creativity.

Fumbani: And, and the iron[ic] part of that—

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And we are in a democratic state, after 1994. And during 2010, up to now, most production were, which are politically intended—a

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: Most are banned from being performed. The censorship board is very critical on that. But you go back—

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: In the days of one-party system, dictatorship was everywhere. Censorship was very tough.

Maxwell: Yeah, very tough.

Fumbani: But more political plays were being written and tough ones, and you could see none of the productions were being banned.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: I didn't have any record of Du had been banned from stage.

Maxwell: You see that because he was crafting. We had a way of invading what the censorship board to a point where, they could not have any excuse to ban your play, because it did not expressly say something directly to say, this is attacking A, B, C, D. So it was difficult for them to ban. That was part of creativity, because when you're a creative artist, now you have your own way of… It's like poetry: you want to say something, you don't just say directly.

Fumbani: Directly, yeah.

Maxwell: You put it in a figurative way where somebody will have to sit down and say, “I think this guy, he wants to say this.” That's what art is all about. Other than a newspaper article, which is just straightforward and saying, oh, A, B, C, D did this and did that. It's different. So yeah, the movement in terms of political landscape has also changed something in the theatrical.

Fumbani: Yeah. And maybe it's a blessing after the deserting of all the donors. The banned of French Cultural Center, you decided to go into secondary schools, and again, call 2010, 2009. I was one of the students in secondary schools.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And you would see theatre groups coming up to for several productions, and that was a blessing for the youngsters, because more youngsters inspired, including me.

Maxwell: Yeah. Right. You're a project of that. Yeah.

Fumbani: Including me. So maybe did discover something from the secondary school that way back did involve this, the secondary schools as to be part of the theatrical world.

Now, the few veterans that were there were mostly directors of those groups that now bring up all these youthful actors and actresses, training them on how to write.

Maxwell: Yes. As you're saying, it was a blessing because the feel of the youth were neglected much, because theatre are mostly focused on the working class, the students and all that. It wasn't much on, it wasn't involving then they were outside. They would just jump in simply because everybody was like, "Okay, we are going to watch a, Du Chisiza Jr. play." And stuff like that, because it was the in thing at the time. But there was not deliberate effort that was made to improve theatre for students, like in schools, schools. There was an effort that was done by the teachers. They used to call it ATEM, Association for Teaching English in Malawi, and stuff like that. They were doing it simply not for theatrical reasons, but for English.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: You see that. So there was, now this movement, now the banning of plays in certain play, the banning of French Cultural Center, and also the lack of space in communities, drove us into schools. Much as it was like an alternative—

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: It was also a blessing for the students to experience theatre. Because now, if you were to be assured that if I go to a particular place, I'm going to find an audience that was only a school.

Fumbani: School.

Maxwell: It's not a place. When you go to a community, the place, it depends on how much you are pumped into advertising for people to learn that you're going to perform, and also depending on how that particular community love theatre. But in secondary schools, you will less assured; if I go to such secondary school, I'm going to have probably three hundred people, four hundred people coming to show me to my show even though the charges were so little. But it could keep us moving, and it keeps us moving. And it also kind of brought this kind of interest in students for theatre.

Fumbani: Okay.

Maxwell: Because way back then, doing theatre was like, you're just wasting your time. Parents never encouraged their children to go into theatre because it seemed like there was no future in theatre in general.

So we moved from Du Chisiza era in the nineties, and now we came to the years of donor syndrome, in era 2000. And then the donors went out and there was disaster.

Maxwell: There was silence.

Fumbani: There was silence. Then we came around 2012.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: 2012, 2013, whereby we could see theatre artists with passions again.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Coming back to the industry. And on top of that, we could see youngsters as well, working with veterans to revamp theatre.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: And currently, how do you look at the situation of theatre in Malawi, currently?

Maxwell: Currently. As you said, you have rightly put it. I'm seeing that the passion is coming back.

Fumbani: All right.

Maxwell: More especially is being fired up by the youth because they are also, okay, they're the ones that they have something to say the society. And they know that theatre is one of the best way of expressing yourself, of expressing almost everything. So coming to the 2012, going 2013, theatre was coming back. The same passion that was there in the nineties was coming back. The youth more especially, it was being speared, spearheaded by the youth, that really wanted to keep things moving.

Now, the few veterans that were there were mostly directors of those groups that now bring up all these youthful actors and actresses, training them on how to write. And they, actors and actresses that were like youthful, were so passionate, and they wanted to learn more about the skills like writing. “How do I write a play?” And all these kind of things. So we began to see now youngsters becoming playwrights and directors having youthful, dramatic outfits emerging, which is a good thing because that's now how an industry grows. Other than if you have only the veterans playing the leading role, then in the end, when they move out of stage, you find that there's science.

Fumbani: Right. Yeah. All right. I think maybe ATEM played a vital role for this.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And you always see the coming, ATEM was there. And the coming of NASFEST—

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: It's a festival for young people. They were coming in over, I can say, the revamping of French Drama Festival. After the French Embassy went out, then you could see, they came back to revamp the festival. It helps the industry to come back.

I've seen you several times on the panel. So time with the panel.

Maxwell: Play the role mostly. Okay. When be on the judging panel of ATEM, I've been there for also the French side, the French, the competitions. I've also been in the panel. So we mostly have become kind of mentors for the youth, for them to actually understand how this is done and how that is done. That's the role, now we can say we are much interested in to groom the youth so that they understand what theatre is all about. And also have that passion actually to instill passion in the youth, what is it mostly important. Yeah.

Fumbani: Alright. Okay. Currently, as I said, theatres is back, right? It's there. We can see more production coming.

Maxwell: We see actually spirit is there. Yes.

Fumbani: But we still have a problem whereby audience… we don't have audience. Yes, we can say we are competing with the digital element technologies just everywhere. We have some social media. We have those phones. We have Netflix and all those stuff.

Maxwell: That's it.

Fumbani: But what's the main issue that theatre can go upwards, and what's the problem? What's the hiccup we theatre right now?

Maxwell: Okay. That's a very good point. Now, theatre now is suffering in terms of audience. I believe it is because of stereotypes. The people think that, okay, now, because we have so much digital platforms, so theatre people are no longer in love with theatre. But you see, theatre has always been there, and it will always be there.

Fumbani: You are right.

Maxwell: A live performance is different from any other performance—

Fumbani: For sure.

Maxwell: Because you're experiencing some raw talent at work. You see, it's different from watching a movie where a lot of editing took place, and what you are seeing was rehearsed several times, and there was a take one, take two, take three. Maybe we take twenty.

Fumbani: You could feel, It's a makeup thing.

Maxwell: Yeah. Yes. You want a particular emotion. You have to work on it, maybe three days you're working on a particular emotion to come out in order for a scene to look good. But when you come to, it comes to stage, you see raw talent. You see real talent at work. So I know that people still love live theatre, right?

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: But because of almost the decline of theatre in the early 2000, maybe the late around 2010, 2011, there about, you could see that people had lost faith in theatre, right. The dying of Legends Du Chisiza Jr. dying, Gertrude Kamkwatira dying, Charles Siveli dying, John Nyanga dying—all these people that were looked at as symbols of theatre dying or these guys. It gave a kind of feeling to the audience that we will no longer experience the kind of theatre that we experienced in the nineties.

We no longer experience the kind of theatre that we have experienced with these guys that have died, because they felt like these were the only people that could perform to those kind of standards. But what these people forgot was that these people had people under them who were learning. Now, the audience had to give these trainees the benefit of the doubt, because that's the time. Now we emerged with our own theatre companies, and oh, we moved around and we could feel like the people underrated us. They felt like, “they can't be like Du; they can't be this kind of thing.”

Fumbani: Yes.

Maxwell: So, I think it was a stereotype whereby the audience felt like, because Du Chisiza Jr. is no longer live, therefore we can't experience the same theatre like we did.

Fumbani: And also discover on your point.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: Whereby if the mainstream media. When they want to cover production, get a production, they wanted to reflect if they, is there anyone who did with Du Chisiza, Gertrude Kamkwatira, those system. But you could see the contemporary theatre now.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: It follows with the trend of technology, the trend of audience, because children who were born in 2000 can't enjoy theatre of the nineties. That style is gone.

Maxwell: That perspective.

Fumbani: Right. And I have seen that. And right now, what I'm happy is I'm seeing production and whereabouts collaboration between youngsters. And the legends, the veterans. They're collaborating. They're mixing the styles of theatre. And currently, for the first time, we have Malawi International Theatre Festival for the first time in Malawi since theatre was there.

This theatre festival is a tool that is going to help us develop theatre. We are going to interact even with international audiences as well as international artists.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Right. So, which is the very good thing. And you must be heading the festival as the president of association.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: Now, let's go back to the association, as the president of association with your team, what are you doing to sustain the theatre industry?

Maxwell: The good thing is, I came into theatre, in the theatre industry in a different era in which we did not rely on donor funding.

Fumbani: All Right.

Maxwell: We relied on ourselves, and we believed in ourselves. And we believed that even without money, if you have talent, you can still do something. You can do, and people would still have it. And so we want to instill that same kind of feeling where we don't want people to just want, okay, fine. We do have cause of proposals, or there's a call for proposal for those that want to do A, B, C. No problem with that. We can do that, but you should not base your theatre on that.

Fumbani: Okay.

Maxwell: Because what if you can… We have experienced a very dry season as artists of COVID-19, in which we were not able to do public performances. Survival for us was so hard and so tough because we rely on performing arts. But you can see that in every kind of situation, an artist will always find a way of expressing himself.

Fumbani: Yeah, for sure.

Maxwell: Regardless of whether there's a donor or whether there's no donor. So National Theatre Association, what we want is to revamp theatre in Malawi. We want theatre to come to where it has always been. Most importantly, we want to build an audience because that lost trust that we have had. We want to restore that trust in the audience. We want the audience to experience the best from the theatre practitioners, as it has always been. Now, because the same people that used to love theatre in the nineties are still there today. They might not be patronizing theatre much because they still want the theatre of the nineties. There is nostalgic. They still want to bring back the nineties into the 2000 and 2022, which cannot happen.

They just have to know that theatre evolves. It evolves. It depends on what an artist is feeling at the particular time. He wants to express himself based on his current environment. He might speak about, we might take do a production of 1915, We might do that, but we are not living in 1915. We just want to bring back people to how used to happen way back.

Fumbani: Yeah, sure.

Maxwell: But now the audience is beginning to realize that. No, I think theatre is in different stages and the different phases. We cannot expect the same theatre that used to be there. Like Shakespeare spearheaded a kind of aesthetic style of theatre, but if you go to England today, you will not experience the same theatre.

Fumbani: Theatre for sure.

Maxwell: Was in 18-something and the Shakespeare kind of stage. They're doing it still, but with different new elements fused into the old kind of style, you understand? That's what we want. We want theatre to come back. We want theatre, theatre audience to come back and experience the same glory of theatre that used to be there by giving these youngsters, by giving the theatre practitioners of today a chance. I would say the benefit of the doubt.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: Let's go and see what these guys are doing. So then they're experiencing, that theatre is coming back. They're saying theatre is coming back. It has always been there. It's them who we are just kind of disappointed because of the death of legends. And then they went out, but I believe that theatre has always been there. But the audience felt like maybe because so-and-so has died… So as National Theatre Association, we have come back. We have come with this International Theatre Festival for the first time. This is an element that has been lacking in our theatre industry because it's like, you know, we did not have anything where we could say, “Okay, every year we have this particular thing happening.

We know that we focus and we know that, okay, we are developing our theatre go industry by using these tools.” So this theatre festival is a tool that is going to help us develop theatre. We are going to interact even with international audiences as well as international artists. So this experience of cultural exchange with artists from different countries coming to Malawi, experiencing our own theatre, and we also experiencing their theatre, is also part of theatre development, which has not been happening probably for many years. Yeah.

Fumbani: Yeah. All right. Still, in the association. We know the association is affiliated with the government to Department of Arts.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: What are the plans between you and the Department of Arts to work out in the theatre? To look on the essence of theatre education? Right now, only have University of Malawi, which has a program of, in drama. Not necessarily theatre, it's just like you minor theatre—one of the programs. And you look of performing arts in primary schools, secondary schools. In secondary schools. We only know students practice drama only for a festival. They want to do an English festival, right?

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: And what are the plans? Cause roots are very important for the future. Roots are very important for the future. And on top of that, you are looking essence of education and also the part of the commercialization of the productions. What are the plans between you and the government?

Maxwell: There are big plans. Recently, we have engaged with the government in terms of creating education, theatre education for practitioners. We do have a lot of people that entered into theatre simply by way of passion, but they might have not received some kind of formal education in theoretical studies. So we have negotiated with the government, and they told us that they intend to study a program with MUST.

Fumbani: All right.

Maxwell: So that we could have a theatre, well custom-tailored course, which theatre practitioners who are already in the industry can also go and learn more about the theoretical part, the theoretical part of theatre.

Also, we intend to introduce certain more—especially the most important thing, as you've said, is also the basic, where you're sewing your seeds. The secondary schools, it shouldn't just be a question of, because there's a second competition or somebody has initiated a competition and then they get involved in theatre. But to deliberately come up with probably drama clubs in secondary schools.

So as National Theatres Association, we also have those plans to initiate those kind of clubs in secondary schools whereby by the end of the day, maybe we could end up having a competition, but knowing that this, we have people that go there and train these students on what theatre is all about. We could take people that are already practicing theatre, those very people that would be taken maybe to mature entrance in universities, to do maybe theatre studies, they could be used. Some people to go to schools now and share that knowledge.

Fumbani: Right.

Maxwell: Because they have a combination now of practical and theory. It is very easy for them now to go back to schools and also teach. So we know that the, we call it the DOA, the Department of Arts is, has working on models on how to train even musician, to training people already practicing musicians, also theatre. Do they want to do it in almost all disciplines. They have that arrangement, probably the political will, because the department is not well funded. It always gets the least. Because of that is what has actually stalled our progress in theatre. Currently, you've also heard that we are spearheading, we are moving, we are lobbying for the establishment of the arts council, Right? That is also a backbone.

Fumbani: For decades, fighting for that.

Maxwell: Developing us in any country. Because this is where now all the policies that want to be used to develop arts will be starting from. If we have an arts council, it is the arts council that will sit down and say, which areas do we need to develop and how much money should we devote to, this or that area or that area in terms of developing the industries. So we are looking up for arts and creative, cultural and creative industries. How can this be developed without the funding from government?

You see, because we cannot continue to say, Oh, everybody should man for himself. This industry can develop that. It's just like any other industry. There have to be policies. They have to be real concrete plans to deliberate plans. The thing does not develop on its own. You actually sit down and plan for that particular kind of development. So we are also pushing the government to pass a bill, which is called the National Arts and Heritage Council Bill. If that bill passes every at discipline will be receiving a subvention from government for the development of that particular sector. So we know that now we can begin to speak about development.

Fumbani: All right, okay. From education in Malawi, we don't have more spaces for theatre performances. Conducive environment for theatre performances.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And those spaces, they're the ones that generate income from the book office, right?

Maxwell: Yes. Yes.

Fumbani: And what are the plans as well for that part of commercialization? Despite that, we need to push more people to do performances with passions. But apart from passion, sustainability needs to be there for the whole theatre organization, for the whole theatre company, for the association, for the individual artist himself. Right.

Maxwell: Yes. Yes.

Fumbani: So I think we are lacking that element of commerce, of marketing our product, like theatre product. And what are the plans in the association, or I can say as an individual artist, you are. What do you visualize about this?

Maxwell: Yeah. This problem has been around for quite some time. They believe the problem of having no conducive environment for theatre at performances. We do have places, maybe hotels, maybe we also have certain other places, private owned places where people do go and do performances. But probably if you check, you realize that these places were not built for theatre. You understand?

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: Theatre has specific needs, and if those needs are not met, what you do? Simply, you just do something because you want to do it, but you don't have lights, proper lighting systems in a particular space. You probably do not have all the gadget that are needed for a theatre practitioner to do his art in a way that he wants to do it.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: You are lacking in one area. It's either, there's no lighting system is either, There's no sound system. It's either there is, the stage was designed in a different way simply for weddings and not for theatre practitioner. You have to improvise and create wings and say, this is the left wing and the right wing—all these kind of things. They become daunting for the performer. If you are going to perform in a place, you have to think of how to recreate the stage. Instead of just going there with your creative thing. You have to say, “Now how do we do a production in this kind of space?” It becomes a daunting task for the artists.

Fumbani: I mean, it even affected the production—

Maxwell: It affects the production.

Fumbani: Or you will have to divert it.

Maxwell: Very right. I remember there was a certain production, we had a certain festival, and there was a production from Zambia that came from Malawi. They were doing the production at the French Cultural Center, but it was done being done at the amphitheater outside. Now, the production had a certain sequence and where the guys were running; there was some kind of a riot and they were running. They were running. It seemed monotonous to a point where people said that production was so boring. It was monotonous. Those guys were just running and running and running. But now when we interviewed the guys that were behind the production, they said, “No, this production is very beautiful.” If you watch it inside where there are lights, because those scenes are varied by using lights. Sometimes you'll see that it's nighttime, sometimes not. Those effects could not be brought on daylight at performance.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: You see, so there are certain things that will affect a production. Maybe, when you writing that production, you had this element how you wanted a certain scene to be conveyed, but because certain elements are not there, the scene does not convey the right emotion, you understand? Now it kills your production altogether. So what we want is, we know that when you go to the government and ask them about spaces, they always say they have plans. But I've always said it takes on the political will of the government. But we know that once we have this, the arts council in place, the government has no choice but to fund that art council because they can't develop an act and not fund it. It's not possible. So it is a must that council will receive money.

Fumbani: Money, yes.

Maxwell: You understand?

Fumbani: Yes.

Maxwell: Now that money now is what we are going to be using for developing arts now as development is infrastructure. Because if we don't have infrastructure in place, where will these people, it's like having asking farmers to go and do a lot of farming without the market for them. We must create a market for that theatre. Now. The market is creating spaces that will make even an audience enjoy the experience.

Fumbani: Yes, yes.

Maxwell: You understand. Because the environment also adds a certain good element to your performance. Yeah.

Fumbani: Right. Okay. Max DC.

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: Thank you very much for today's edition.

Maxwell: You're welcome.

Fumbani: You have went through situations in Malawian theatre—

Maxwell: Yes.

Fumbani: And I'm just happy because all those areas of theatre in Malawi. You were there and you are right here today. And you are, we’re witnessing something change in theatre in Malawi. And on top of that, the conversation itself will go outside. People will see how base we can do it. The stakeholders will jump in. The government will say, Okay, I think this is the right time.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Cause we need to be activist our own industry.

Maxwell: I see.

Fumbani: Right.

Maxwell: I see.

Fumbani: But oh, thank you for this, for coming with this platform. And your voice is very powerful, and the conversation will change the theatre industry in Malawi and also add something to the world.

Maxwell: Yeah.

Fumbani: Yeah.

Maxwell: I'm very thankful for even this chance that could communicate with the people so that probably people out there could learn the kind of challenges you're facing and the kind of triumph we have had over the years. So thank you. It was a pleasure.

Fumbani: Thank you.

Thank you so much for having a chew with us. This has been another episode of Critical Stages in Malawian Contemporary Theatre. I was your host Fumban Innot Phiri Jr. If you're looking forward to connect with me, you can email me at [email protected].

This episode is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episode of this series and other HowlRound podcasts in our feed, iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and wherever you find podcasts. Be sure to search “HowlRound Theatre Commons podcasts” and subscribe to receive new episodes. If you love this podcast, post the rating and write a review on those platforms. This help other people to find us. You can also find the trust of this episode along with a lot of progressive and disruptive content howlround.com Do you have an idea for exciting podcast essay or a TV event that theatre community needs to hear? howlround.com and submit your idea to the comments.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Powerful conversation