Jessie Mill (Festival TransAmériques, Montreal): Sure, but aren’t you just reproducing a broken system in the game rather than changing it? Why not make a game to outline the changes you want to see in Canada’s performing arts community? Especially given the state of the industry at the moment.

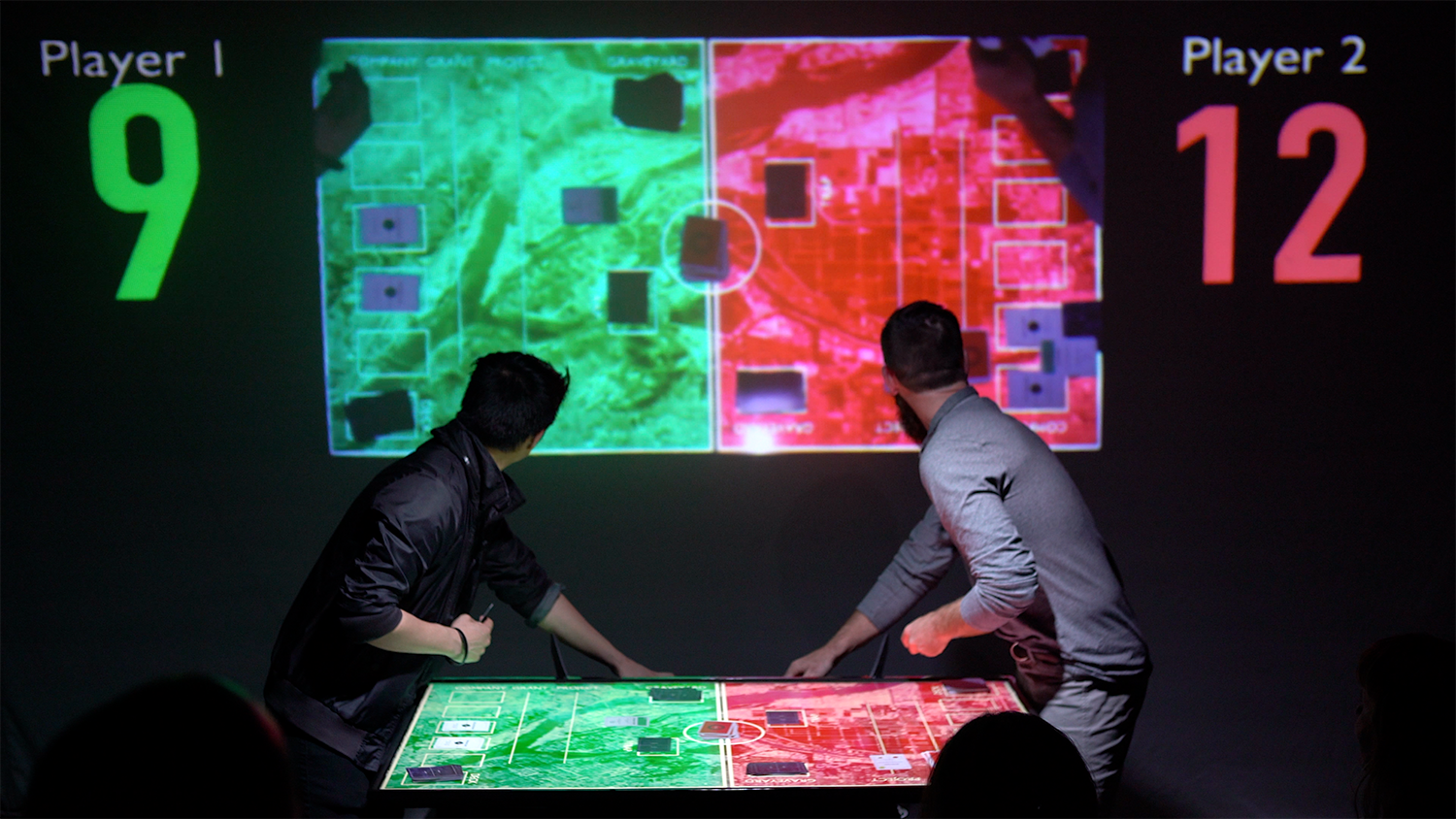

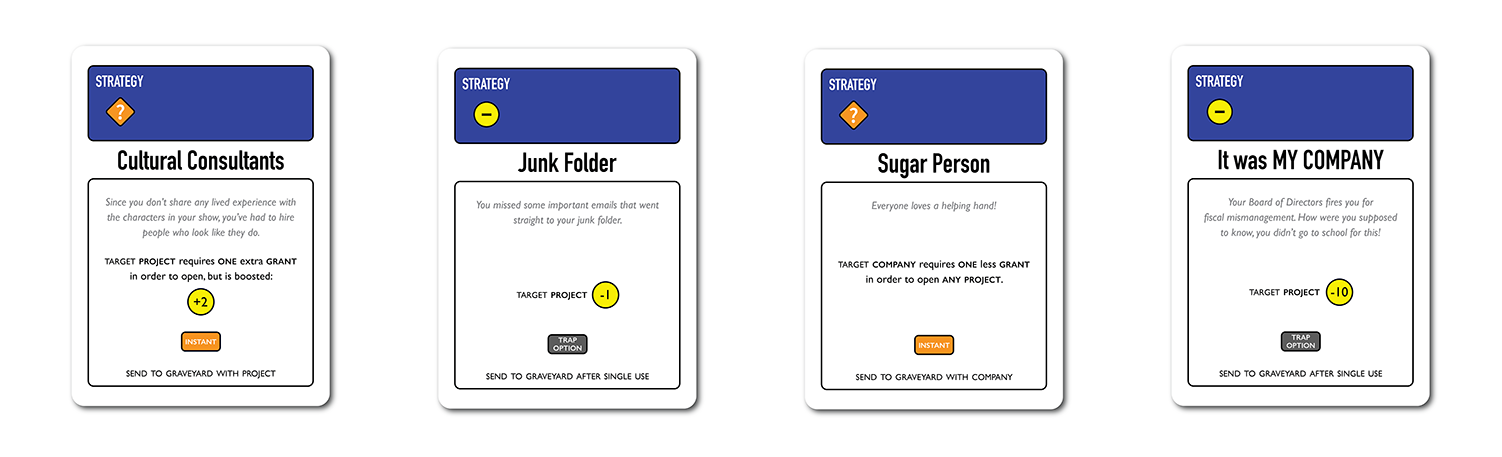

Patrick: That’s true. culturecapital is not a blueprint for systemic change. It is not an instrument. However, to go back to our core goal: it does create a context for conversation, reflection, and critique. From that space, blueprints can be concocted.

Milton: If we wanted to tell people what to say and do, we’d have written a play and not made an open-ended game where different narratives emerge depending on what cards get played. At the beginning of making culturecapital, there were some artists who recommended that we script our presentations of it. Which is also called “cheating” in any card game and completely misses the point of why we are making it.

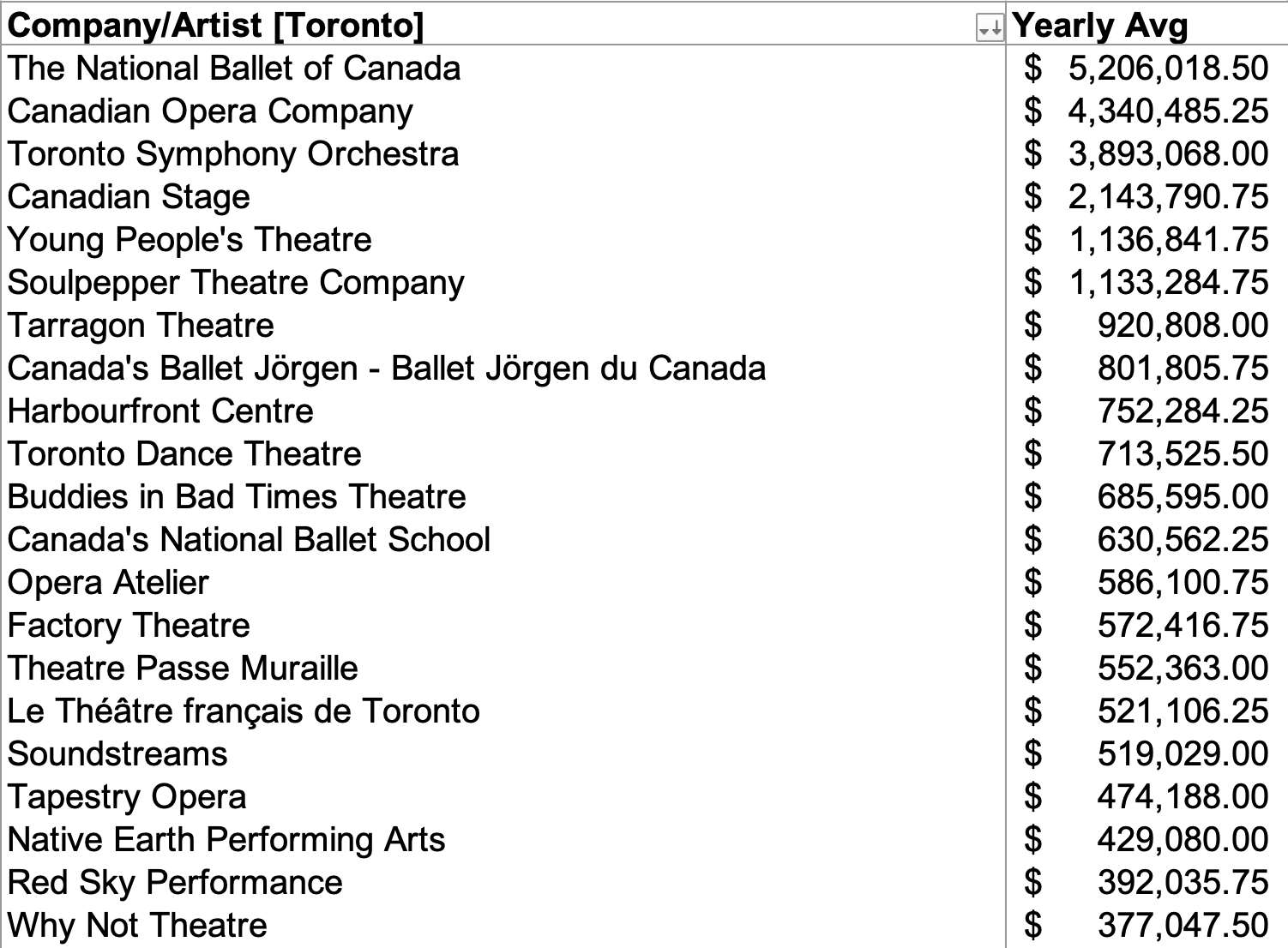

We want to see more transparency in our highest funded arts institutions. We want to see these institutions engage more rigorously and thoughtfully with art history, performance history, and their global contexts.

Alex McLean (Zuppa Theatre, Halifax): I get that. There’s a cult of worshipping playwrights and respecting scripts to the letter in Anglo theatre culture. It makes me think about how games often have house rules where the “script,” or rules, become more suited to the players.

Patrick: Right, eh? Even though the game is a standalone object, it’s not fixed. People can change the rules of culturecapital and reimagine the industry. We’d love that.

Milton: Regarding changes we’d like to see as artists outside of the context of culturecapital, we certainly have our own thoughts and desires. We want to see more transparency in our highest funded arts institutions. We want to see these institutions engage more rigorously and thoughtfully with art history, performance history, and their global contexts.

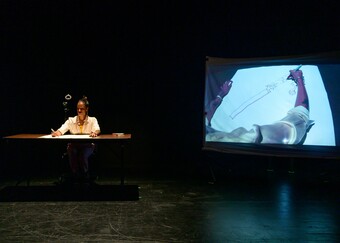

Patrick: We also want to see more performance-makers in Canada be more rigorous in learning from each other’s work. From the interviews we’ve done in numerous cities, people have noted a significant lack of awareness of their peers’ work and aesthetic values. In July 2019, we started a separate project, videocan, specifically to address this need.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here