“Our history is moʻolelo, the stories of gods, ancestors, and the lessons we learn from them. To Hawaiians, folklore is not fiction. It is our genealogy.”—Kumu Hula Kimo Keaulana

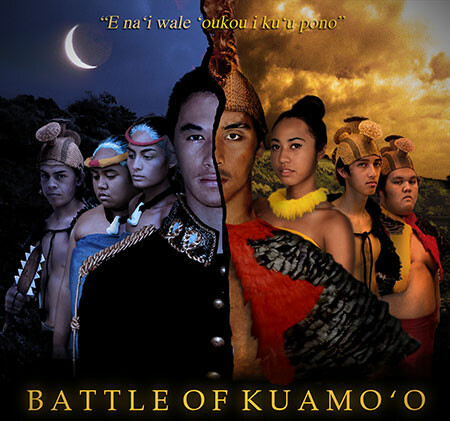

Hawaiian Theatre, known as hana keaka, is making its presence known throughout the islands of Hawaiʻi. By combining a Western theatre structure (stage, lighting, props, script, acts, etc.) and Hawaiian history (folklore, newspapers, biographies, songs, chants, genealogies, etc.), a new indigenous theatre form has been born and is now being reared by Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) artists in every part of the island chain, ranging from elementary students at Hawaiian language immersion schools to graduate students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

What’s the common factor driving these adaptations of Hawaiian stories onto stage? Education. Hana keaka not only serves as an opportunity for indigeneity to be celebrated on stage—its main purpose is to include and educate all of Hawaiʻi’s people in demonstrating the value of revitalizing Hawaiian language and culture. It is one movement of many to re-normalize and re-institutionalize Hawaiian language throughout the state of Hawaiʻi, and a tool to immerse oneself in the Hawaiian language, to hear and experience popular stories from an indigenous perspective.

Hana keaka not only serves as an opportunity for indigeneity to be celebrated on stage—its main purpose is to include and educate all of Hawaiʻi’s people in demonstrating the value of revitalizing Hawaiian language and culture.

What is hana keaka (Hawaiian theatre)?

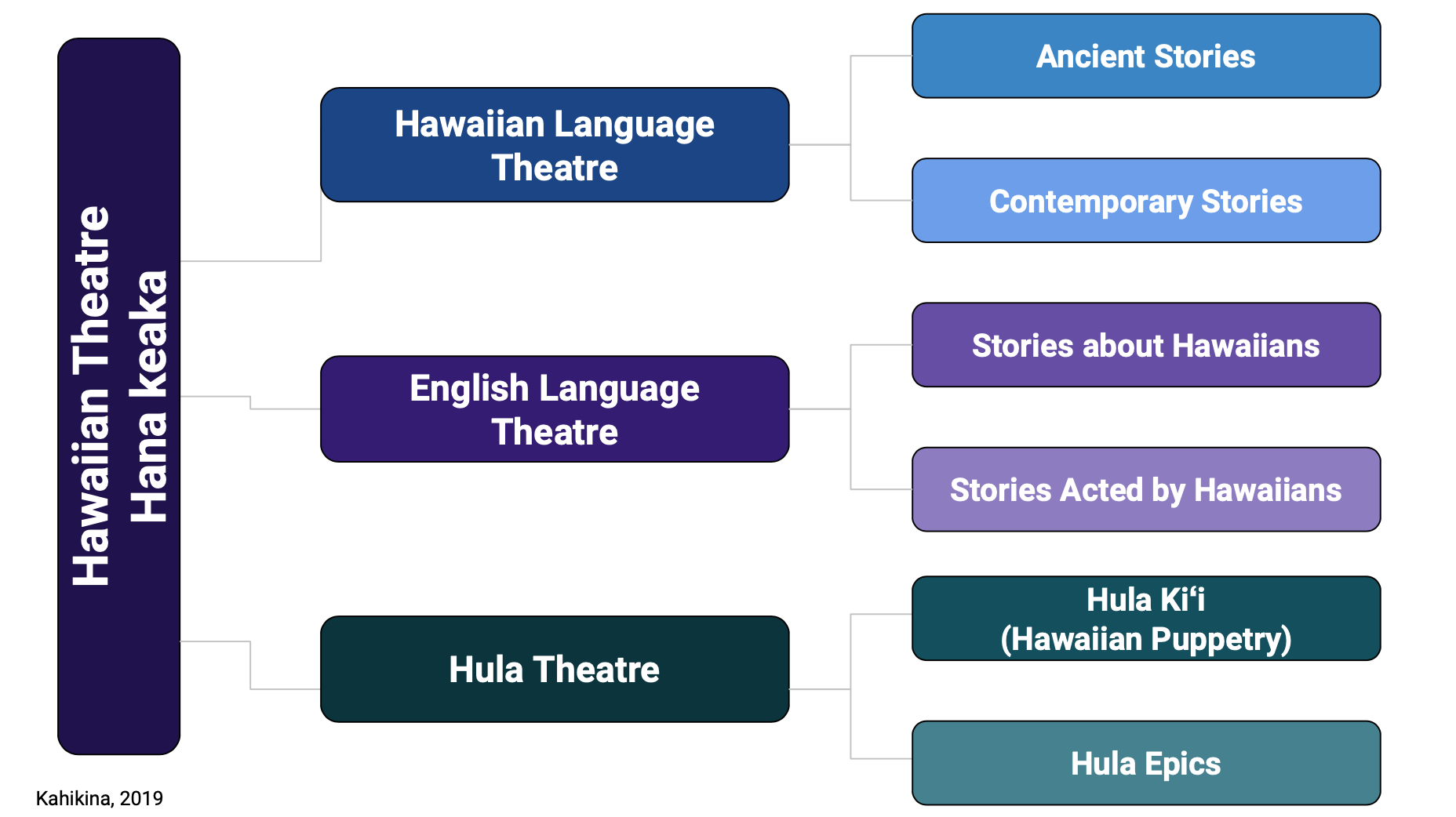

According to Hailiʻōpua Baker, founder of the Hawaiian Theatre program at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, hana keaka is defined broadly as “...dramatic works that utilize the Hawaiian language to propel the story forward.” Baker also points out that there are four integral components that differentiate hana keaka from western theatre forms that make it uniquely Hawaiian:

- Moʻolelo: bases plot with a dramatic story, epic, or historical event related to Native Hawaiians

- Moʻokūʻauhau: integrates and interweaves genealogy and ancestral knowledge

- Hana Noʻeau: demonstrates mastery of fine arts, such as hula (dance), mele (song), oli (chant)

- ʻŌlelo Hawai‘i: uses native mother tongue as dialogue or narration

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here