Touching Time

Choosing Gay Heritage in The Gay Heritage Project

In her book Performing Remains, about war, re-enactment, and performance, theatre scholar Rebecca Schneider said that what interested her about historical re-enactments was “the attempt to literally touch time”—that is, through touching time, we might somehow commune with it in all its permutations of the past, present, and future. Time being what it is (either a vexing metaphor or a dimension of the universe, depending on your commitments and in either event necessary to our own conception of our existence) we can’t actually touch it so much as feel it, and in feeling it we give a name to time that has passed: history, change over time. Along with our sense of history, we maintain a hope for the future–for what will be. And left between these two points, continually vanishing, is our present moment. Our lives are a continual spectral interplay between past, present, and future.

I mention this because the show in question, The Gay Heritage Project, at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto, is not the Gay History Project. It’s about more than just gay history (setting aside for a moment the question of whether it makes sense to talk about such a history, of which more in a moment); rather, the show is about making sense of a heritage and in doing so it raises the very interesting questions of how performances are both manifestations of heritage and repositories of heritage. This show is an archive, a question, and a living artifact all at once.

This show is an archive, a question, and a living artifact all at once.

According to the Center for Heritage and Society at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, “Heritage is the full range of our inherited traditions, monuments, objects, and culture. Most important, it is the range of contemporary activities, meanings, and behaviors we draw from them.”

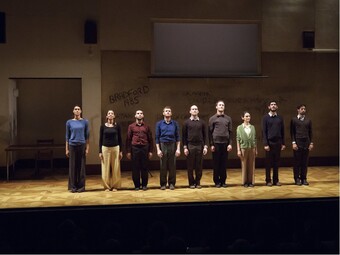

Taking a similar view as their starting point, creators/performers Damien Atkins, Paul Dunn, and Andrew Kushnir created a show exploring myriad components of gay heritage, all the while questioning whether such a thing can actually exist. Drawing from a Vocal Masque technique taught at Alberta’s Grant MacEwan College, the performers developed vignettes on the theme of “Gay Heritage,” defining this as narrowly or as broadly as they chose for each vignette, ranging from deeply personal stories of their own coming out to metatheatrical scenes about making the play itself. Some examples include a delightful Sondheim musical pastiche, a Gay Canadian Heroes segment modelled on action-hero commercials, and scenes that wrestle with the historical conception of “gayness” and homosexuality. The result is the delightful feeling of bits and pieces coming together to make a whole as eclectic as the modern gay community.

Undoubtedly the greatest strength of the piece, directed by Ashlie Corcoran, is the interweaving of the personal histories of the three creator/performers with the milestones of gay history in Canada and elsewhere, along with scenes that are actually derived from the process of making the show. It is in this way that the piece manages to be both a living artifact and an archive of gay heritage. To cite only a few of the most poignant examples, Atkins’s scene of his boyhood-self acting out Olympic figure skater Brian Orser’s silver-medal routine from the 1984 Olympic games in his living room, only to be walked in on by his father is delightful in both the innocence of it and in his father’s knowingness of this stereotypical gay behavior. Likewise, Atkins’s representation of Dunn’s Scottish mother upon finding out that Dunn is gay is touching in its warmth and understanding, and humorous in her bigger concern that Dunn has taken up smoking.

Kushnir’s scene where he goes to the Ukraine, his family’s ancestral homeland, to speak with gay men there after his mother told him there was no such thing as a gay Ukrainian man is powerful as Kushnir realizes that his mother is right: these men, whose sexual and cultural lives must be lived underground in a deeply homophobic country are not gay in the same way that Kushnir is, humorously depicted in their astonishment as he tells them about the very existence of the gay theater in which we ourselves were sitting. Atkins, Dunn, and Kushnir are acutely aware of the great mantra “the personal is political” and their presentation of their own stories helps to solidify this fact within the world of the play.

Atkins, Dunn, and Kushnir are acutely aware of the great mantra “the personal is political” and their presentation of their own stories helps to solidify this fact within the world of the play.

In addition to their personal stories, they dramatize their encounters with gay history as a component of gay heritage. None of the performers were alive when the Stonewall Riots ignited the gay rights movement in the United States, and they were very young children when the Operation Soap raids against gay bathhouses awakened a similar political consciousness in Canada in 1981. The worst of the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s is, for them, a piece of history, as Atkins memorably discusses when he places HIV on trial as empty chairs are illuminated from behind a scrim. They live in a time and place where gay people can legally marry and enjoy the same civil rights as everyone else (at least in Canada; the battle for equal civil rights remains ongoing in the United States), and yet as gay men their lives are informed by this history of “otherness” and of vocal critics and outspoken advocates. This history is honored throughout the play. In one delightful scene, Gay Identity, dressed impeccably in a dinner jacket and on his way to some gala or another, takes a shortcut down a dark alley and finds his forgotten and discarded compatriots, Gay Desire, Camp, Drag, and Joan Crawford hanging out in the shadows. The anxiety in this metaphorical encounter is hard to miss.

The scene that was, for me, the epitome of what the show accomplishes was (surprise, surprise) a spoof of The Wizard of Oz. In the scene three Friends of Dorothy are walking along the Yellow Brick Road in search of gay heritage, only to finally arrive to confront the wizard and discover that the man behind the curtain is none other than Michel Foucault, whose work permanently shifted, for better and worse, the way we conceive of and discuss sexuality and sexual identities. Although initially disappointed to find out that the Wiz himself determines sexuality to be a social construct, and therefore the search for an immutable gay heritage to be futile, he does offer them some sage advice: “maybe, heritage is what you choose.”

Heritage is what you choose. Just click your heels together and…

The creation of heritage–of what we choose to commemorate and how we allow that to inform our present and the future we want–is born out of that desire to “touch time,” to deeply feel the history and hope for the future that make us part of a community. What The Gay Heritage Project accomplishes is to capture a slice and a sense of that community through a piece of art that is both a repository of heritage and is, I believe, an expression of that heritage in itself. Simultaneously subject and object, past and future, The Gay Heritage Project shows that heritage is really about living in the “vanishing present.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here