Writing for the Moon (and other adventures in object theater)

Sometimes, and here comes a confession right out of the gate, I write puppet shows. Well, you may say, that’s charming, or so retro, or great for kids! But those aren’t the reasons I love this medium.

Puppetry suits me because it’s fundamentally collaborative, and I’m most inspired when authoring alongside others. I’m a storyteller, and the art form I love—theater—can tell a story in many ways: through dance, song, movement. Theater can be, like film, a visual art form. Sometimes objects and images can take the place of words.

What unites the puppet theater with other devised forms is that in it the writer is merely part of a dynamic collaboration. As a playwright, I’m part of a team. I am not necessarily The Source. In a recent essay on this site, Meiyin Wang pointed out that theater texts in the 21st century are increasingly authored by duos, trios, by machines, by groups.

But a corollary that is rarely discussed, perhaps because it makes playwrights squeamish, is that sometimes a writer in the theater is in service to another person, to a project, or even to an object.

Puppetry in the 21st century

Puppetry is the bastard nephew of so-called legitimate theater. It’s the black sheep of the family, a scrawny kid playing with the food on his plate at the family gathering.

Yet puppetry stubbornly persists, even flourishes, in our digital age as an intentionally Luddite approach to an emphatically live art. Seeing people breathe life into hand, rod, marionette, or shadow puppets through subtle manipulation reminds us we are watching something happen now. Projecting a video on a wall is easy. Making a “live cartoon” using shadow puppets and classroom-style overhead projectors is a delicate and difficult art. Redmoon, the company that introduced me to puppetry in many forms, recently performed a giant comic-book-style sci-fi epic called The Astronaut’s Birthday on the façade of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Thirty-six overhead projectors and thirty-six performers were elaborately choreographed with hundreds of hand-inked figures and backgrounds. This memorable live experience drew thousands of Chicagoans to the city street to see a public space transformed into a massive puppet theater for an evening. The text, an outlandish story penned by Tria Smith and performed in voiceover, was an important element of The Astronaut’s Birthday. But the core of the performance was the spectacle.

Seeing people breathe life into hand, rod, marionette, or shadow puppets through subtle manipulation reminds us we are watching something happen now.

What puppetry has taught me, as a writer, is not only that a story can be conveyed through images and objects, but that sometimes the most indelible live experiences in theater originate not from a writerly but from a visual impulse. In those cases, the playwright’s job is to serve those images, and not the other way around.

The puppet comes first

Of all forms of theater, puppetry is perhaps the most given to magic, to surrealism and sheer invention. It is an exciting thing to work with a group of adept trained performers, ensemble-style, to discover ways to tell a story through movement, spoken text, characterization. But even more delicious, in my experience, is to plan a scene featuring the Moon as a major character and know that in a moment, a small wooden planet with a face can appear from behind a table, and open his mouth, and start to sing. The world of the play changes in an instant.

In puppet theater, the writing doesn’t always come first. To really write for the Moon it is often necessary to see the puppet first. To enter, as a writer, into a dialogue with a physical thing. This is because the puppet brings its own personality to the table. It is stubborn, it wants to express things in a certain manner, it is humorous in one way but not another, it moves with grace or with thudding awkwardness.

Objects that bear the action

An example: in Boneyard Prayer, a 2008 folk opera I wrote for Redmoon, I created lyrics for three characters—a man, a woman, and their dead son. I didn’t write for more characters because it wasn’t in my power to invent them. The characters existed, because they had been designed and built by Jesse Mooney-Bullock, a remarkable artist who carves highly expressive bunraku-style puppets out of wood. The man, woman and child weighed nearly as much as real people, and were almost life size. They were made of paint, wood, leather, and glass eyes. They had to be muscled into place by teams of puppeteers (one on the legs, one on the torso, hands and head.) I wrote songs associated with these characters, and developed a storyline featuring only these characters. I didn’t have a choice. The puppets were my constraint, and everything I did had to serve them.

The project, and the puppets, were the brainchild of a third person, the director, Frank Maugeri. Because puppetry is grounded in design and the visual over the verbal, puppet theater is a director’s medium. In the room, a writer is often merely another contributor of material. The writer’s words can either serve the objects, or fail them. The writing may take the foreground in moments, but the piece rises and falls on the action of the objects.

This can be difficult. Sometimes, in rehearsal, Frank and I would disagree about the story, about the storytelling, about the lyrics, about the staging—about everything.

“The puppet can’t do what you’re suggesting,” he would point out, about things like picking up a dollar bill. “He wants to do this instead.” He’d show me, and suggest I write a different song. Then we’d talk some more.

The difficulty of working in this way is one of the reasons that puppet theater is often comprised of individual puppeteers designing, writing, building and performing their own work. This is sometimes a good idea, but all too often is not. As in most theater, the art generally turns out best when multiple minds, with various strengths, are engaged in specific tasks.

Writing for the moment

The fact is, writing in service to an object very often means writing without being grounded in the literary playwriting tradition. It means letting go of the goal of having the writing published, or produced in regional theaters, or on Broadway, or even ever again. Being a director as well, I understand this feeling. Most directors realize that their work will likely never be performed or produced again after closing night. In reality, this is also the case with most plays.

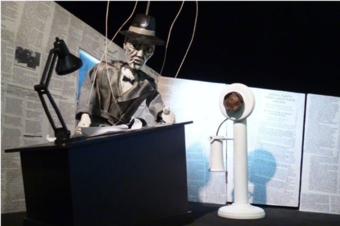

There’s something good about embracing this. One of my favorite writing projects was a twelve-minute opera about the first dog in space, titled Laika’s Coffin. I created the show with Frank (who’s now Artistic Director of Redmoon and was also the creative force behind The Astronaut’s Birthday). The script for Laika’s Coffin is basically just a collection of lyrics and some text for a faux-Russian narrator. In recent years, I’ve added some stage directions for the sake of explaining it to presenters, but they are very workmanlike: “The Moon awakes. The Moon sings.” These statements, both to a presenter, and to you reading this essay, have little impact without an accompanying image of puppet designer Kass Copeland’s remarkable Man in the Moon puppet with working mouth and majestic face— wan, mustachioed and serene.

We’ve performed Laika’s Coffin several times, including in Minneapolis and New York, and at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Not bad for a twelve-minute puppet show. But despite the show’s success, I’d never send the script in for a playwriting competition. It just doesn’t make sense without the production. Maybe I’m wrong—but I don’t think so. It’s a work of art that has a particular form, and if people are interested in it, it comes with a production, puppets, music and all.

Writing for a family

It is possible that some of the best writing for the theater results from authors being assigned tasks with tight parameters and accountability to a producer or collaborator, if not to a collection of wooden puppets. Stephen Sondheim, in his excellent book Finishing the Hat, writes about writerly constraints, self-imposed and otherwise, with gusto. In a revealing moment, he shares his feelings about collaboration:

“I have to work with someone, someone who can help me out of writing holes, someone to feed me suggestions when my invention flags, someone I can feed in return. To be part of a collaboration is to be part of a family.”

That’s the Moon and me. And the Moon’s lesson applies throughout my creative life.

I’m currently writing a musical—well, the book for a musical (my colleague Gabriel Kahane is handling music and lyrics). This (non-puppet) piece, titled February House, offers me the best of both worlds—the literary and the devised. I have the autonomy to write dialogue, imagine characters, events, narrative arcs. But I’m beholden to and constrained by the music, the form of the “musical.” It’s wonderful—there is a container, and a dialogue—a very active one—with my writing partner, Gabriel, about each element in the book, lyric, and score.

And in the musical theater, I’m encountering something else I love: specific critical feedback. A trusted producer or outside eye will sometimes say “this song doesn’t work” or “this scene isn’t good enough.” And then I will improve it, or try to defend it. It reminds me of Frank pointing out that the puppet, graceful though it is, can’t pick up a dollar bill. So cut the song, or make it work another way. It is a relief not to be coddled, told that my expression is valuable because it is my expression. I want to make something that inspires my collaborators and that lands with my audience. Call me old-fashioned. And that’s why, for me, writing puppet shows and book musicals are part of a continuum, in which the author’s place is central but rarely sacred.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I am part of a puppet theatre company in Washington, DC, and what excited me most about your article was that we have such similar understandings of the role of puppetry in 21st century theatre.

I have to disagree with you on one assumption. I am a playwright for our company, and my approach to writing for puppetry is the exact opposite. There are almost no limits to the world of puppetry. I open up my imagination and write on an epic scale without thinking about the mechanics of the show. When my company sees the script, then we begin talking about how puppets will be built and how stuff will work. In our process, the script is the jumping off point for the designers, director, and puppeteers. I challenge them by giving them tremendous images and then we are able to create extremely innovative work (within our small budget) because we have to figure out how to make a puppet break into pieces and then be put back together on stage. That is what excites me about puppetry! The human body has limitations in what it can do on stage night after night, but a puppet has no limitations.

Having said that, I can't wait to see your work and thank you for introducing the topic of writing for puppetry to howl round!

Thanks, Seth for this insightful essay. It's great to hear a writer really get what it is to write for puppet theatre. I've been working as a puppeteer for 20 years and I tend to write/design/direct most of the shows for the reasons you mentioned. The times I've worked with writers, I've had to convince playwrights who are used to envisioning a whole world as they write that puppets don't act, they do; some ideas and emotions would be much more effective if you can show through puppet staging and imagery, not through words.

I'm going to keep a copy of your essay and show it to future collaborating writer at the beginning of the process.

This is a lovely article.

I think you build a really smart connection between performance, plays, and collaborative creation by offering some concrete ways to address varied understandings of authorship.

I also think, though you don't reference it specifically, that you usefully frames 'devising' and community-engaged process on a spectrum of activity, rather than a binary, (written/not written) which i think is super helpful, especially for artists looking for alternative models through which they can make.

Indeed, writing doesn't always lead.

As a maker/writer, i know that doesn't mean that the writing is less real, demanding or potentially excellent.

Thanks for writing about my new favorite art form - and I am familiar and greatly respect the work of Redmoon so great to hear some of the things that have been happening there earlier.

I am currently working on an object manipulation puppetry piece that is utilizing common objects in the daily life of a person to interpret works from the theatrical canon (the other night we rehearsed Macbeth and Lady Macbeth arguing about "doing the deed" as butcher knives standing over a piece of meat representing Duncan). I am a director who has been increasingly interested in puppetry and it didn't make sense to me why until you said it was a "director's medium". So true! Particularly so when you are adding puppets to scripts that not originally intended for the form. No wonder I like it.

That said, I do think you should be able to submit your plays to contests and other theaters. I think the exciting thing about theater and scripts that have stage directions like "the moon sings" is the multitude of wonderful interpretations that can emerge from them. As a theater company and a director, I relish and look for scripts like this. That's the joy of what writing for theater can be - a multitude of productions can take your work to places you never could have seen coming.

I've never responded in this form before but felt compelled by this piece which is insightful about theater and, yes, performance art, which I admit to as my practice with a nervous awareness of being perceived as retro. Puppetry, of which I know little, but which you make clear here -- as I regard performance art --is theater expanded from the long held Aristotelean, modern, and contemporary definition strictures. The statement of a playwright admitting reliance on the theater process for me harkens back to Sophocles himself, who was first an actor, as was Shakespeare, and how many others, is grounding.

Enjoyed this article,something about its theme and tone was fresh, inviting, moved me forward in wanting to learn, experience more. Also added its own twist of insight for why I like the move BEING JOHN MALCOVICH so much.