Why I’m Breaking Up with Aristotle

This week on HowlRound we continue our exploration of Theatre in the Age of Climate Change, begun a year ago, in honor of Earth Week 2016. How does our work reflect on, and respond to, the challenges brought on by a warming climate? How can we participate in the global conversation about what the future should look like, and do so in a way that is both inspiring and artistically rewarding?

It’s me, of course, not him. After all, Aristotle and his posse of ancient Greeks gave us many of the elements that have become the foundation of Western civilization. They gave us human rights, democracy, and the Olympics. They gave us philosophy, significant advances in mathematics, and medicine. And they gave us dramatic structure, the golden principle behind all of Western dramatic literature.

That’s a lot to admire, I know. But I’m still breaking up with him.

The thing is, our relationship has run its course. Given the new challenges brought on by a rapidly changing world and our inability to communicate effectively around them, and given the fact that I feel he doesn’t really see me as a woman, it’s best we go our separate ways. I have no doubt he’ll continue to be influential in my life—we had many good years together and I will forever value the lessons I learned from him—but in the end he’s too controlling and I need to break free.

To be completely honest, I’ve been feeling a growing discomfort for quite some time. It wasn’t exactly boredom, and we were not fighting either, but we didn’t seem to fit anymore. Round hole, square peg type of thing. And then, not too long ago, I came across Josephine Green’s presentation “The Power of Abundance.” Boom. Suddenly it all became clear.

The idea is this: Though Aristotle and his pals gave us all the good things mentioned above, they also subtly imparted their worldview and its attending values to us. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. That worldview has allowed human civilization to thrive for over twenty-five hundred years. But in the context of a world that is now massively different from ancient Greece—more populated and exponentially more connected—that worldview has become a liability rather than an asset.

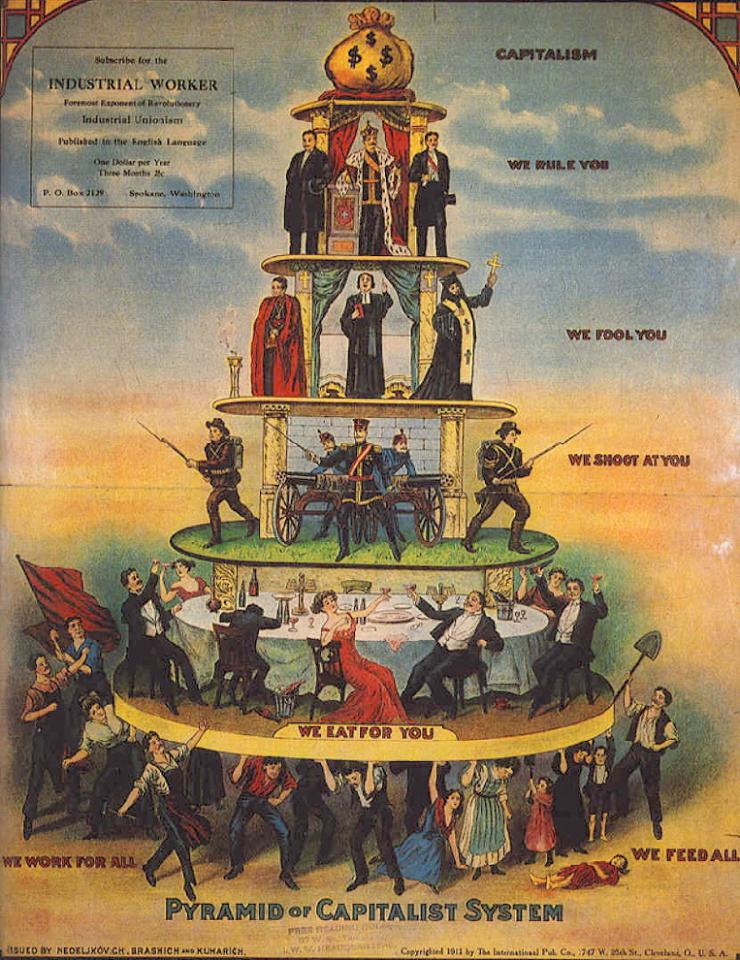

On the most basic level, ancient Greeks were ruled by a bunch of unpredictable gods whose whims directly affected every aspect of human affairs. Largely ignorant of the natural forces shaping life on Earth, people assigned power and knowledge to these supernatural beings and lived under their capricious rule. Then, as empirical knowledge developed through the study of science, some of the powers previously assigned to gods became better understood and a single Almighty God replaced the jolly bunch. The Almighty God prevailed until the industrial revolution when our increased resources and self-reliance moved us away from the divine and into the arms of mega-corporations.

Though these represent big shifts in how we conceive the world and our place in it, the underlying assumption—that power is at the top and everybody below is subservient—has remained unchanged. In fact, it is so deeply embedded in our culture that most of the time we don’t notice it.

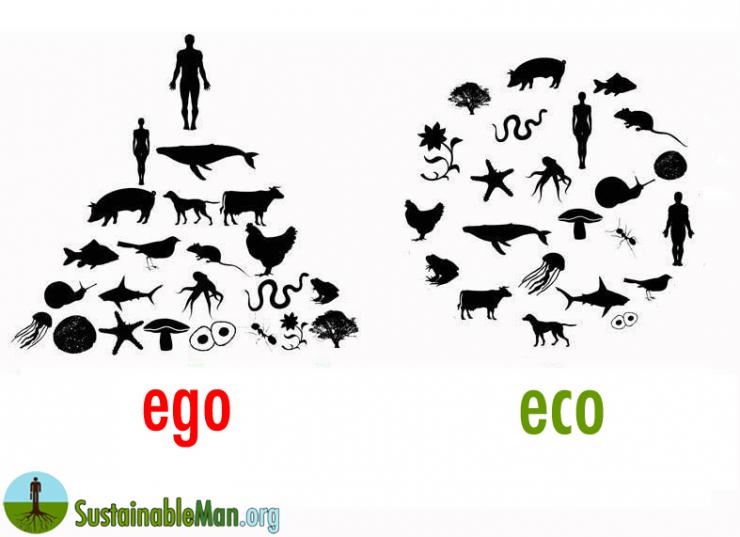

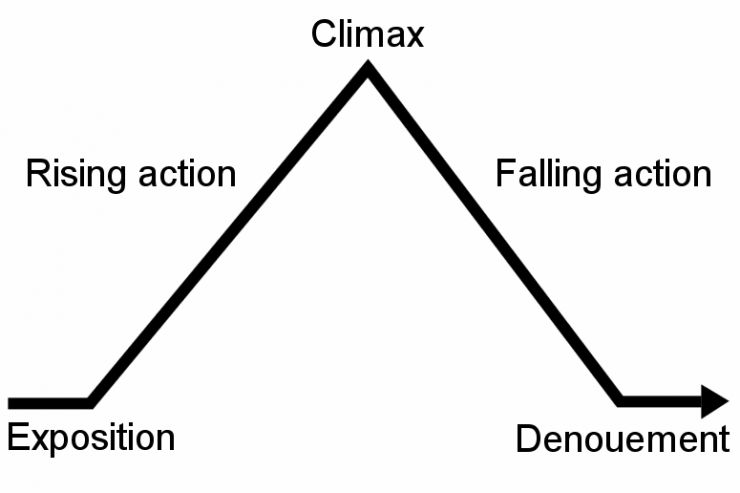

The simplest way to illustrate this concept is with a pyramid. Power and wealth live at the top, in the hands of a minority, while the majority exists at the bottom to support the top. This is how religions are organized, how monarchies thrived, and how today’s capitalist system functions. But as Green points out in her presentation, the pyramid model is not an absolute truth. It’s a worldview. Or, put another way, it’s a function of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. It should come as no surprise then that the structure we use to build our societies, and the structure we use to shape our stories, are one and the same. Aristotle’s theory of dramatic writing, later modified by German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag, is a pyramid. Rising action on one side, climax at the top, and falling action on the other side.

This form of storytelling flourished at a time where man needed to conquer in order to survive. Life was hard; nature, a hostile force to be reckoned with; and other nations, a constant threat. Subjugating nature was a matter of life or death, while subjugating the masses was a way to secure power and resources and to build a sense of security. As this worldview and the stories used to keep it alive were passed down generations, they were (and still are) used to justify a slew of abusive behaviors such as feudalism, colonialism, slavery, genocide, violence against women and children, economic injustices, the plundering of natural resources, etc. In addition, Aristotle excluded a very important point of view from his theory. The festival of Dionysus, where ancient Greek theatre began, was for men only. Aristotle’s “core data” was in fact stories written by men, for men, and about men.

How can a dramatic theory developed in these conditions represent the world we live in today and the world we are striving to create? We’re living through an unprecedented transition in human history where we’re slowly shifting from a hierarchical worldview to a heterarchical worldview. New technologies and social digital media have created a complex world and, in the process, flattened the pyramid into what Green calls a pancake, with relationships organized laterally instead of vertically. Given this new paradigm, is it ethical to embrace a dramatic form that was designed to justify inequality and violence? Can we, writers, say something new, something of value, if we don’t break free from that mold? If we don’t find a way to write ourselves out of the pyramid?

My friend Koffi Kwahulé knows this problem intimately. An African playwright born and raised in Côte d’Ivoire, Koffi spoke his tribal language at home and was taught French—a legacy of French colonization—in school. He was also taught playwriting according to the classical French tradition. But, like most of his contemporaries, he realized that the experience of colonialism can’t be expressed using the language and forms of the colonizer. Koffi had to find a way to appropriate the French language and make it sing a different song. He had to develop a dramatic form that would express his own unique experience. Over the next thirty years he developed a unique aesthetic, akin to jazz music; in the words of NYU professor Judith Miller, “Kwahulé intends his theatre—with its stylistic nods to jazz, through its riffs, refrains, and repetitions, through references to composers and musical numbers—to capture both something of the pain of contemporary existential despair and the exuberant energy of improvisation.” Borrowing from a form developed by African American slaves struggling to maintain their cultural identity, Koffi reconceives jazz music to express the pain of French colonialism and, by extension, the pain of oppression.

What we need today is a conscious use of dramatic structure in service of societal change.

The idea is not new. Many playwrights—including Beckett, Churchill, Pinter, and Kushner, just to name a few—have played with form. But they did so in isolation and it could be argued that their concern was mainly aesthetic. In contrast, what we need today is a conscious use of dramatic structure in service of societal change. The hierarchical pyramidal worldview is based on values that promote competition, control, and a sense of scarcity—there isn’t enough to go around. And since we have to fight for everything, there will always be winners and losers. The heterarchical worldview, on the other hand, promotes innovation, collaboration, and creativity. It works with the assumption of abundance—there is enough. We just need to learn to look for it and distribute it more equitably.

Moreover, writing plays where scenes have a neat cause-and-effect relationship in the internet age, where ideas emerge through associations and where biomimicry is replacing old mechanical principles, seems archaic. And with quantum physics telling us that two realities can exist at the same time and that an observed behavior is forever changed by the act of observation, shouldn’t we explore all the possible realms of existence and consciousness rather than stick to a thin sliver of observable reality? Humans are not the center of the universe anymore. Time is no longer linear. Our species could go extinct. These are profound ideas that should inform how we structure our stories.

I’ve seen some exciting plays recently that grapple with these concepts. And these plays have both nothing to do with climate change and everything to do with climate change. None of them addresses the topic directly. But embedded in their structure is an attempt to break down the many pyramids that rob us of power and agency, and to view humanity as part of a vast web of life. O, Earth by Casey Llewellyn, Smokefall by Noah Haidle, and CollaborationTown’s Family Play (1979 to Present) all possess a new sensibility that positions us within a larger and more compassionate frame. These playwrights are seizing the moment, they’re sensing what’s floating in the ether and responding to it. They’re creating the sustainable culture of tomorrow.

For us writers, there can be no formulating a new vision for humanity without a shift away from the Aristotelian pyramid of classical dramatic structure.

In her book This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein argues that we can’t fix climate change using the economic system that created the problem in the first place. In The Heart of Sustainability, Andres R. Edwards explains that we can’t create a sustainable future unless we change the culture of shortsightedness that’s ushering us to the brink of catastrophe. If we are to change our culture and the stories that create culture, it follows that we also need to change how we tell those stories. Just like for Klein, there can be no lasting solution to climate change without a shift away from the pyramid of free-market capitalism; for us writers, there can be no formulating a new vision for humanity without a shift away from the Aristotelian pyramid of classical dramatic structure.

So this is it. For better or for worse, I’m breaking up with Aristotle. I don’t harbor any bad feelings towards him; I did love him. For a long time, our relationship was fun, passionate, and intellectually stimulating. But then things changed.

Maybe I grew and he didn’t. Or maybe it was always meant to end this way, with us going down our separate paths. It’s the end of an era, that’s for sure. But it’s also the dawn of a new age. Though it’s not easy to leave the comfort of the known and knowable, I’m excited at the possibilities that lie ahead, at the chance to craft stories that are in line with my values and my vision of what the world is and can be. I’m excited to do my part and to bring all of me in that effort. I think I’ve earned the right to.

So long, Aristotle. It was swell.

Oh, and happy Earth Day.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Great article about Aristotle very informative thanks for sharing

While one hopes that society is changing and our relationship with the world around us is becoming more compassionate and aware, I'm afraid that Aristotle's pyramid is still relevant because people haven't changed in 5,000 years. We still struggle for survival, for dominance and power, we are still the same short-sighted, self-centred beings we were when we first emerged from the ooze; a less linear, cause and effect dramatic structure cannot prevail until human nature is transformed.

Maybe you and Ari could reconcile. His "theory" does not have to be connected to hierarchical dominance - he just needs to take his own ego out and realize he was not creating rules, he was describing orgasm. You both could create a dramatic life where you give good play and take a new position by including us, the audience, in a shared moment of climax.

Tita Anntares (www.anntares.com)

Btw, NYTimes Thomas Friedman's book "The World is Flat" is also relevant.

Reconcile, or be part of a circle together standing at different locations. I've read Chantal's points to be that, if we hew strictly to what we've inherited, we miss the opportunity to hear other stories in other ways. Had the privilege this year to give a playwriting workshop in a very diverse high school, and nearly half of the participants were African (not Af-American). I (Anglo Guy) did what I was paid to do, which was deliver the Full Aristotle, but as the day want on, and during a follow-up session when they brought in first drafts, I had the nagging feeling that we had probably excluded other storytelling frameworks. In a couple of cases, when students wrote about events in African settings, I found I was really dying to know how they would have brought these stories forward themselves, without prompts to engage Ari's structure. The students, bless them, appreciated the structure and the knowledge of this background — it's not evil. But I wish I could have given them more, and I want to think about how to do that.

Maybe you and Ari could reconcile. HIs "theory" does not have to be connected to hierarchical dominance - he just needs to take his own ego out and realize he was not creating rules, he was describing orgasm. You both could create a dramatic life where you give good play and take a new position by including us, the audience, in a shared moment of climax.

Tita Anntares (www.anntares.com)

PS NYTimes Friedman's book "The World is Flat" is also relevant.

Maybe you and Ari could reconcile. HIs "theory" does not have to be connected to hierarchical dominance - he just needs to take his own ego out and realize he was not creating rules, he was describing orgasm. You both could create a dramatic life where you give good play and take a new position by including us, the audience, in a shared moment of climax.

Btw, NYTimes Friedman's book "The World is Flat" is also relevant.

http://www.openculture.com/...

I broke up with Aristotle long ago, but I'm not sure theatre works for social change. This sounds an awful lot like the Socialist Realism theatre of the Eastern Bloc.

From THE FEMALE HERO IN AMERICAN AND BRITISH LITERATURE:

“Our understanding of the basic spiritual and psychological archetype of human life has been limited, however, by the assumption that the hero and central character of the myth is male. The hero is almost always assumed to be white and upper class as well. The journey of the upper-class white male—a socially, politically, and economically powerful subgroup of the human race—is identified as the generic type for the normal human condition: and other members of society—racial minorities, the poor, women—are seen as secondary characters, important only as obstacles, aids, or rewards in his journey” (4).

Great quote.

You might be interested in this: http://stilleatingoranges.t...

I'm not sure the link is coming through. It's a blog post about plot without conflict, in the Japanese tradition. Hopefully you can find it sometime.

This is great. Thank you.

But you do realize your essay has an Aristotelian structure to it. He's sneaky that Aristotle.

:-)

I was hooked from the title of this article but remained genuinely surprised throughout. The title suggested a break up letter to Aristotle that would contains qualms with his patriarchal beliefs and narrative structure but delivered so much more. I was intrigued with the links drawn between his views that put man as the highest importance and authority in a society and subsequently the most important in the stories that we tell. This article reminds me that as a portion of the storytellers in the world we have a responsibility to present views and create realities that we want to be present in our world. Aristotle's story structure has shaped our society into a force that has sustained to this point but will soon burn out. We continue to tell a story where the smallest portions in the story or the wealthiest in a society are at the top and the rising/falling actions or poor are simply used as the forces to propel the "climax." I agree that this is extremely problematic and it is up to the storytellers to change the shape of the stories we tell and the message we want reflected. I was so happy to have found this article. I have been struggling with some of these larger ideas and finding the links to other parts of society helped me breakdown the idea even further.

I'm glad the article was helpful to you.

Aristotle was a scientist, not a dramatist. He was not trying to tell theater makers how things should be, but rather what works and why. Action and reaction are still the basis of all physics (quantum included) and plays that lack causality will always be doomed to the recycling bin.

Aristotle defined causality as being the one thing that necessarily has to follow another in order to move the action forward. I'm saying that this definition is too restrictive now and that causality can be fashioned in a lot of different ways that are more expansive than what Aristotle initially envisioned. In quantum physics an action causes a number of possibilities to be revealed. There isn't a one-to-one exclusive cause and effect.

I suppose so, but we don't live on the quantum level. That stuff is fascinating (extremely so to you and I, it seems) but we live on the cellular level; in a world where phenomena, like global warming, have specific causes and specific effects. Also, causal structure has certainly been employed to examine these quantum questions. (If/Then, Sliding Doors etc) Anyway, just one fellow playwright's opinion. Your article is certainly evocative! (And lo, isn't that the point of a think piece?)

Have you read Brecht's critique of Aristotle? I think the two of you would find some common ground. :)

I get your point. And I'm happy the article is giving us the opportunity to exchange ideas. I've never read Brecht's critique of Aristotle (or if I have it was in graduate school and I don't remember). Thanks for the recommendation. I'll take a look!

I’ve been wrestling with this article for a little while and I’m still not sure how to respond. While I understand the author’s view, I’m not sure the argument is whether or not to break from traditional structure; rather, the argument seems like it should focus on what stories are being told…and that is an entirely different conversation. Most recently, I think of how effectively ‘Disgraced’ used traditional structure to provoke dialogue on Islam and how well that play was received. I don’t see traditional structure as a negative—it is simply one container of many containers to communicate a story. Further, traditional structure CAN be manipulated—it is not a means to an end. If a writer is struggling with the structure of a story, then the writer is—of course—free to find a different container. It’s a stretch to look at the traditional dramatic “pyramid” in correlation to hierarchical power. To do so diminishes what comes before and what comes after the climax…that’s too simple an approach to playwriting—too shallow an approach to storytelling. Back to my original point, it seems like the article is attempting to discuss what stories are being told and how they are being told…I’m not sure that has anything to do with Aristotle. Are there still arguments about patriarchy, capitalism, greed, heteronormativity, etc.? If so, I’m confused. None of these details inherently exist in a play with traditional structure…those details are provided by the writer…not inherently found in the structure of a play.

I respect your point of view but I do think that structures, as much as content, communicate a specific message. It is true in the world in general: Government structures, economic structures, family structures are all a reflection of a specific set of values. And then within those structures we find out how individuals enact their own personal stories. I think the same is true with playwriting.

If societal change is the goal, then what is the most effective structure for transformation? Is there one answer to that question? Ultimately, whatever story is told, it needs to be a great story. We can continue to disagree, but I think it is short sighted to dismiss traditional structure. If any writer is going to break up with Aristotle, that is certainly their choice...but new structures of storytelling will need to reach people, inspire them, provoke thought, and advocate for ideas. Traditional structure can do all of that...as can other structures of drama. I still advocate on focusing on the kinds of stories that are being told for societal change. I know you believe that the structure itself includes limitations...you didn't explicitly state that, but you did indicate that structures contain values, those values communicate specific messages, etc. I think there is a place at the table for every structure to advocate for social change. Writers need to choose for themselves what approach they believe is most successful for their work and the goals of their stories—such as social change. I don't believe writers need a new structure in order to imagine a new future for humanity—writers need to tell stories that have an impact on audiences.

I agree with you that all writers don't need to break up with Aristotle. Everyone should be able to choose what works best for him or her. However, being conscious that we are making a choice when we use the Aristotelian structure goes a long way. The traditional structure has long been the unquestioned default. Everything else was considered "experimental." I don't actually know if there is one most effective structure for transformation but I believe the challenge of trying to find out is worth it.

I'm completely jazzed by this piece. Best thing I've read on HowlRound in a while.

For my own work as a writer and performer, I've begun to find that fiction narratives themselves have also lost their usefulness. I'm writing in a kind of associational non-fiction style now, linking ideas in a syncopated, jazz-inspired way. It feels more like building a network, rather than a pyramid. And it feels right to me.

Thanks for your comment. I'd love to read some of your work. Where can I find it?

Now that we're Facebook friends, I'll send you something :)

Great!

Hi Chantal, I am breaking up with the guy too! As a matter of fact, we have been parting ways for about 3 decades. But, the funny -- or maybe 'tragic'-- thing is that, alas, my STUDENTS do not seem to want to let go of the paradigm. Just last week in a senior level Latina/o theater class (I am a part of the Latina/o Theater Commons right here on HowlRound) my predominantly Anglo theater majors and I had a discussion about the 'well made play' (they in favor/ me against). Me: "This class is about THEATER... not just 'plays'. Must everything that goes up on stage, i.e. the theatrical experience, follow Freytag's pyramid? WHY? Who says?" They: "Professor, the Aristotelian dramatic concept has been around a looong time, so there must be some good reason why it would withstand the test of time.... It is emotionally more satisfying for the audience to know there will be that structure." Me: "But aren't we TIRED of it yet? I am!" I am several decades older than they are and, apparently, much more open-minded to change. And, THAT is disturbing. Thank you for your article, I will certainly share with my classes.

Thanks, Teresa! I think part of the problem may be that people don't have enough of a reference frame as to what non-Aristotelian plays might look like. Or maybe the references are so "out there" that they can't relate to them. I don't know but it's sad that in a country that so values innovation in other fields (business, for example), there is such a resistance to innovation in the theatre.

Maybe because I come from a Latin American theater background I have seen incredible, innovative work in places such as Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Mexico City. I know Santiago, Chile has a great international theater festival called Santiago a Mil where some of my friends have seen exciting new forms. Lima, Peru and Bogota, Colombia are also huge centers of experimentation with form, and this has been going on since the 1960s. Just go to NYU's HEMI website to see some of it! It is remarkable that the US looks towards Europe and even the Far East but not to its closest neighbor to the South for a creative dialogue. Actually, except for the mega musicals that seem to have tremendous global export value, in Latin America the stuff we see here in the US is perceived as somewhat provincial and antiquated. Oh yes!

Oh I'm jealous! I saw an adaptation of Hamlet once at the Public Theatre by a group from Brazil and I was blown away. I wish I could see some of the works you talk about. I'll definitely take a look at the website.

It's sad that your students' love for one structure doesn't allow them to be open to so many others. With a longer view of history (and I'm sure you've made this argument) we see how many established, currently "safe" works of art in every field were initially unacceptable to the public. Critics who heard Beethoven's Ninth Symphony apparently thought he'd gone mad. There have been walk-outs, vocal and violent reactions and even riots in response to works by Steven Reich, Nijinsky, Stravinsky, Tristan Tzara (okay, his work is still weird, but it's fascinating) and dozens of other creators who are now commonly revered. That's just a random sampling off the top of my head; you undoubtedly have a much more interesting list at your fingertips.

Unfortunately, it's probably impossible for your students to be convinced of the validity of other forms through reason. Ultimately, theatre is what happens in front of you (or around you, but right now while you're there), and it's been through experiencing other forms of structure (and experiments with destroying structure altogether), that I've let go of my preconceptions in the past. I'm lucky enough to live in a city with a lot of small, innovative theatres. It's probably not a coincidence that many of the non-traditional projects that delight audiences in Vancouver take place in venues other than theatres. Getting out of the building is sometimes a good start to help the audience to let go of their ideas of what's SUPPOSED to happen on stage.

A composer colleague likens a taste for experimental music to developing a taste for spicy or strongly flavoured food. If you're used to a more bland meal, you may need to start with mild spices. And at first you may not be sure if you liked what you just ate, but it was interesting enough that you give it another try. With enough exposure, she's convinced people come to crave experimental music the way I regularly crave curries, pickles or strong cheeses.

Wonderful article! Thank you for writing it! I will be sharing with my beginning playwrights who use Aristotle and my advanced students who study and create New Forms -- there are unlimited forms for plays out there is the world, and hopefully we will all continue to create them!

Thanks, Emma!

Lots of food for thought about in this essay, as theatre artists and audiences in this country navigate a theatrical landscape that includes everything from the “well-made play” to experiments in anti-drama. Aren’t all theories of drama attempts to identify organizing principles that will engage an audience in some way? Perhaps the biggest danger of any theory of drama is when an artist builds a play around a theory rather than their apprehension of the world – using whatever organizing principle will best transform that artist’s vision into a meaningful experience for an audience.

Well said!

This article and the video of Josephine Green discussing "The Power of Abundance" started me thinking about theatrical communities and the lack of sharing resources and knowledge I have experienced from company to company. It is as though there is a big competition going on - for scripts, for actors, for audience - and someone is going to win and someone will lose. It made me wonder if this "managerial" structure is actually working against the theatrical community. If our own idea of how things "should be done" is a construct, why not experiment with new models that highlight the strengths of this socio-ecological era?

Totally agree with you!

I've been structuring my plays in this manner for a very long time and for similarly political reasons but was told that it was bad playwriting and that AD"s couldn't "find the event" -- these discoveries re: sustainable structures, inclusive structures, non-male structures are no new thing. Just saying.

Oh! Read Doug Rushkoff's work in postlinear narrative structures. The idea that it's STRUCTURE and not content that contains the really radical message comes, I believe, from Marx. Rushkoff posits that you can discuss challenging CONTENT in a safe structure or safe content in a challenging structure -- because audiences can't take on both at once. Most people think if they say something controversial in an Aristolean play (or conventional "3 act" movie) that they're being "edgy." What's really edgy is to make them reconceive "event" itself (it's not just when a lone man is in trouble! events themselves are relational!) and time.

Thanks, Brooke. I will look up Rushkoff. His work sounds really interesting. And yes, isn't it interesting how difficult it is for people to accept a play as being "worthy" when it departs from the traditional structure? Thanks for paving the way. I've seen one or two of yours and really enjoyed them.

Yes, there are many reasons to challenge that received structure. I'm in Alaska right now talking to Native Alaskans about climate change and they have their own very real reasons to question "received structures." It's eye-opening. I'm happy the essay will be useful for your class.

I have been noticing the success of pieces that are able to describe systems instead of psychology. Aristotle's dramatic structure seems to better suit the study of the failures of human psychology, how individuals are to blame, and how we should endeavor to do better. I appreciate plays that leave this story structure behind, and instead tells a story in mosaic or snapshot, giving us a complex look at the different facets surrounding the center of gravity of the systems that run our lives.

David, do you have a few favorites that you might want to share?

I'm with you, Chantal!

Thanks!

stimulating piece.

Thank you.

Great and challenging essay. Very well thought out - and I am going to add the books mentioned to my reading list. Plus great title - who would not want to open I Am Breaking Up with Aristotle?. However, I am not sure I agree - I think audiences have pre-conceptions about plays that are very hard to break. Maybe new audiences don't - and maybe that is who new forms of theatre are written for I watched audiences at the Goodman very challenged to stay engaged with Smokefall, and many (and not all old people) who left at intermission the day I was there. So, clearly, there would need to be a way to clue audiences in to how to engage with these plays in a different way. Or forget it and just focus on new audiences for this work. It is a dilemma - but an interesting one - and so glad to have you grapple with it with such intelligence and humor. Thanks.

Reaching audiences with new forms is definitely a challenge. It is one I struggle with all the time. I don't know if there's a magic trick -- if there is, I haven't found it. But I think the effort is worth it. Hopefully, if enough of us try, eventually we'll reach a tipping point where audiences are willing to go to these unfamiliar places. After all, if audiences in Europe are willing to be more adventurous, there's no reason why we couldn't slowly teach North American audiences to do the same. Though I have no doubt many of us will (and already do) experience a lot of frustration in the process. :-)

"In Greek mythology, maenads (/ˈmiːnædz/; Ancient Greek: μαινάδες [m]) were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones."

Yes, the drama festival was men only, but the Dionysian cult was not male dominated. Actually marked by androgyny and sexual openness. Also, to call the Aristotelian structure a pyramid is to misread it; the diagram is a 2 dimensional image, but it represents the progression of actions occurring in the fourth dimension - time.

Thank you for your observations. I respectfully disagree about the Aristotelian structure being strictly a 2-dimensional image. Since theatre is a 3 dimensional art form, and plays are enacted through actors' bodies, I think the structure necessarily takes on a 3-dimensional form on stage. The progression towards a climactic moment is a very western concept. Native storytelling, for example, promotes different values and is structured differently.

I was making the same point. It seemed to me that YOU were interpreting the structure in a 2 dimensional way since it's easy to look at the diagram and say, "oh, it's a pyramid." And then aligning it with other pyramidal structures.

And it's not 3 dimensional, it's 4 dimensional (+time.)

Ah! Got it!

Thanks Jeff Wolf Zinn. No Chantal, Jeff said theater is a four-dimension art form, not three. Aristotle proposed a unity of time-space-action, time being the fourth dimension. Now, it seems to me that in your point of view, Aristotle and Hellenic culture sprung out of nowhere by spontaneous generation. Nothing comes out of nothing. The Greeks took from the Egyptians, Egyptians from Babylonians, and keep going back until you get to the Agricultural Revolution in the Fertile Crescent, the second most important shift in the way we tell our stories in the Western World——apart from the cognitive revolution when we Sapiens began to communicate through language. So, why topple old statues to build new ones? Yes, we are not going to change the way we live until we change our economic system. Try to convince the 43 corporations that dominate world economy, whose shareholders are intermingled and amount to a few hundred, that they need to give up their privileges and power. I agree that theater should reflect our present time and foresee the future; or at least ask the right questions. But changing form, this for that is not going to help. I believe life and Theater should be this in ADDITION to that, not this INSTEAD of that.

Josephine Green explains the legacy from the Greeks in more detail in the presentation I link to in the article. To me, her argument makes sense though I agree with you that the Greek culture didn't come out of nowhere. And I do believe a change is needed. There is too much of that and not enough of this at the moment. So I'm advocating for a better balance. I know Aristotelian structure is not going to disappear. But we should be conscious of what we are implicitly saying when we use it. And there should be room for alternative structures in mainstream theatre.

Chantal I am still going to read this great piece again, then I will come back and give out my view about it.

Great!

I see the point of this article. However, without Aristotle, we would not have a foundation for the fields of the sciences, and we would not have had Darwin's theories either. Although as modern theatre makers, we resist the narrative structures of his Poetics, we should not forget that it is thanks to Aristotle that we have the scientific methods of observation and inductive reasoning -- a foundation for studying life itself. That is, how we can identify natural phenomena, or how scientists can track climate change.

We need foundations from which to redirect our ideas, and push against. Playwrights and story tellers have been pushing back again the Poetics for a long time, but there is a lot more to Aristotle than narrative structure. #iwillalwayslovearistotle

I agree with you -- Aristotle and other Greek thinkers have provided the foundation to our Western civilization. I don't mean to discount their contribution, which was invaluable. But I do think it's worth pondering how the ideas embedded in Aristotle's narrative structure might be promoting a certain social status quo that is not helpful anymore.

If you follow the link above, Power of Abundance, you will see a more complete discourse on how Aristotelian approach was a phase of development that might be now outmoded because it cannot deal with the connected complexity that we live in (it has produced?).

Also, on this Earth Day, Darwin was actually directed to his Theory of Evolution by Humboldt who he credits with giving him a unique is seeing the whole environment, cosmos, rather than the reductionist parts.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/03...

One can also credit the ideas embedded in Aristotle with the horrors of this world, which is why a new world view is necessary. The Foundations of Western civilization has not benefited all or all equally. It has also been the source of genocide and enslavement for many people across centuries.

sending it to all my students and putting it up on my own wall

Thanks!

Great essay, Chantal! I'm totally using it in my Playwriting and Contemporary Theatre classes. We've been talking about challenging Aristotlean dramatic structures for a while but you articulate this so well by connecting our playwriting craft to climate change and social issues. Thank you!

I would be curious to hear about the discussions that come out of your class. I'm sure there is a lot to be added to the article and I hope many people jump into the conversation!

Wonderful, Chantal. This was a great morning read that I know I will be pondering and using. And a big amen to you having earned the right!

Thanks, Andrea! Glad you enjoyed it.

Wonderful perspective on our predicament and path out. As they say, those who write the stories write the laws.

Great line. I had never heard it before.

I think I got it from Howlround, or maybe Anne Bogart's book, but it is credited the Scotsman, Andrew Fletcher, as:

"If a man were permitted to make all the ballads he need not care who should make the laws of a nation."

Love it!