Me Too Monologues and Four Principles of Community-Based Performance

“I’m not good at expressing myself and that affects my interactions with others.” I sat nervously in the audience, watching as the first performer spoke her line in what I hoped would begin an entertaining and powerful hour-long performance. Founded at Duke University in 2008 with the goal of allowing for open discussions on race and identity, Me Too Monologues was only in its second year at Princeton University, but had been marketed as the capstone event of the Mental Health Initiative Board’s annual Mental Health Week. In her book Local Acts: Community-Based Performance in the United States, Jan Cohen-Cruz explains her four guiding principles for community-based performance: communal context, reciprocity, hyphenation, and active culture. These four principles can be applied as a framework for understanding the student directed, produced, written, and performed Me Too Monologues because it plays a socially meaningful role in the service of Princeton University’s Mental Health Initiative Board, which relies on dialogue and listening, combines education with community-building and therapy, and allows for a number of diverse performers to share the stories of their peers at free and inclusive performances.

The Me Too Monologues adheres to the first principle of communal context because the “artists’ craft and vision” play a “meaningful role” at “the service of a specific group desire”—that of the Mental Health Initiative Board. Founded in 2013, the Undergraduate Student Government committee known as the Mental Health Initiative Board: “works to increase awareness of mental health…, reduc[e] stigma that may prevent students from seeking help, and promot[e] constructive dialogue across campus to build a more supportive community.” In addition, Cohen-Cruz explains: “community-based art derives meaning from its context; its creators are inspired to make beautiful art because of the socially meaningful role it plays.” The Me Too Monologues responds to the dire state of mental health on Princeton University’s campus, allowing for anonymous students to submit their own stories regarding mental health. On April 20, 2014, for example, an anonymous contributor to The Daily Princetonian describes in an article how they masked an ongoing battle with clinical depression and thoughts of self-harm to retain their status as a university student. In addition to this article, not only did a student commit suicide in her dorm room in January 2015, but another anonymous author’s op-ed, published in The Daily Princetonian on March 2, 2016, opens with the chilling statement: “Sometimes, I want to end it.” The Me Too Monologues is thus a project that plays a “socially meaningful role” in serving the greater vision of the Mental Health Initiative Board.

The ‘Me Too Monologues’ responds to the dire state of mental health on Princeton University’s campus, allowing for anonymous students to submit their own stories regarding mental health.

In addition to adhering to the principle of communal context, the founding mission statement, rehearsal process, and performances of the Me Too Monologues each satisfy the two necessary prerequisites for the second principle of reciprocity: dialogue and listening. In her section on reciprocity, Cohen-Cruz explains how Cornerstone Theater Company’s Artistic Director Bill Rauch “knew there were stories out in the world that never got heard.” This particular sentiment coincides precisely with the founding mission of Duke’s Me Too Monologues as “a forum for those who might otherwise be unheard on college campuses” and “a resource for those on the margins.” Cohen-Cruz also notes that reciprocity “rests on dialogue” and is “reflected in joint ownership of work created by the community from whence it came and the artist/facilitator.”

Composed entirely of anonymous student submissions, this year’s Me Too Monologues included diverse themes ranging from anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder to eating disorders, gender and sexuality, and religion. In addition to the mission statement, both director and performers edited and consistently revised the monologues to establish joint ownership of the work created by Princeton students. Then, three post-show discussions allowed audience members to discuss and explore the issues in an open and public forum. Overall, the Me Too Monologues is a project whose various elements from its founding mission all rest entirely on dialogue and listening.

By allowing dialogue and listening between the director and performers in the rehearsals, and ultimately audience members in the actual show, the Me Too Monologues is a project that adheres to Cohen-Cruz’s third principle of hyphenation. In her definition, she explains, “Community-based performance is hyphenated in consisting of both multiple disciplines—aesthetics and something else, such as education, community building, or therapy—and multiple functions, having as goals both efficacy and entertainment.” While aesthetically-pleasing for audience members through careful lighting design and stage blocking, the Me Too Monologues fulfills community-building through education.

Although this education does not take place in a formal classroom setting, the project seeks to educate audience members on the unshared experiences of their peers, while serving as a foundation for systemic cultural change in destigmatizing mental health issues. In addition to these disciplines, several authors indicated a therapeutic aspect in listening to their stories be shared publicly. For instance, one author stated the following in a personal e-mail: “I cannot describe the emotions I felt while listening to someone else tell my story...Having it presented like that was truly a gift, and left me feeling things that are indescribable.” The Me Too Monologues is both an entertaining and moving performance piece, one that draws audience members in while simultaneously allowing for individuals’ stories to be heard.

‘I cannot describe the emotions I felt while listening to someone else tell my story...Having it presented like that was truly a gift, and left me feeling things that are indescribable.’ —Anonymous

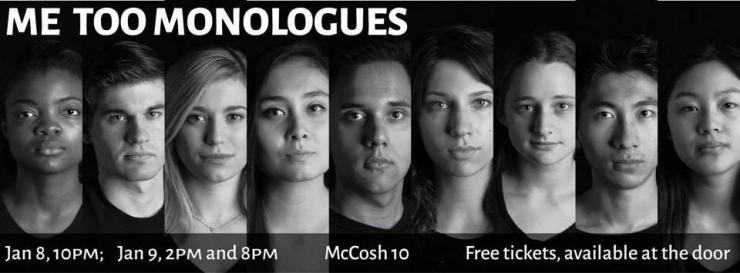

In adhering to the three principles of communal context, reciprocity, and hyphenation, Me Too Monologues is a performance piece that embodies an active culture in which artistic potential, diversity, and inclusiveness are the three main emphases. Cohen-Cruz’s principle of active culture is “reflected in another core axiom of the field—that everyone has artistic potential.” Of the production’s nine performers, four had never before appeared in a show on campus, thus requiring a comprehensive rehearsal schedule to bring the text to life. Six of the performers were women, five identified as people of color, and two identified as LGBTQIA. The diversity of these performers, an important element of active culture, reinforced the range of experiences reflected in the performed monologues. Cohen-Cruz also notes the importance of inclusiveness, describing how an artist “displays her art in the most accessible way, such as low cost of admission, accessible venue, and inviting contexts.” Not only were the 2015 and 2016 Me Too Monologues free and open to the public, the total number of performances increased from two in 2015 to three in 2016 to provide community members with more options. Eliciting the artistic potential of non-performers, the diversity of the cast, and the inclusiveness of the three performances each demonstrate how the Me Too Monologues adheres to the fourth principle of active culture.

By employing Cohen-Cruz’s four principles of community-based performance as a framework for understanding Princeton University’s Me Too Monologues, one can see that this particular production is guided by communal context, reciprocity, hyphenation, and active culture. The Me Too Monologues is an entirely student-run project from beginning to end: the anonymous authors, performers, and director are all working at the service of the Mental Health Initiative Board in response to the state of mental health on campus. The project thereby relies on dialogue and listening from its mission statement through the rehearsal process to the post-show discussions at the conclusion of each performance. In addition to combining aesthetics with the goal of community-building through education, these free and all-inclusive performances feature students from diverse backgrounds to reflect the diversity of students’ mental health experiences. It is my personal hope that as the Me Too Monologues project grows it can encourage a cultural shift in normalizing mental health issues.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Having recently completed several years of episodic research pertaining to mental illness for a play I was writing, I am appreciative of this student organized project and the positive impact it undoubtedly has made with the lives of those involved as well as the community. I also found the other articles via links very powerful and thought provoking. Thank you for sharing and well done.