Chicago theatre

has a lot going for it—in numbers. I’ve heard that there are something like five hundred companies here? Eight or nine indisputable major ones, big LORTs; the rest (proudly) on the storefront continuum, running on anywhere from two-mil-plus budgets to not much more than greasepaint and attitude. Surely one is never bored at 7:30 in the evening, six nights of the week.

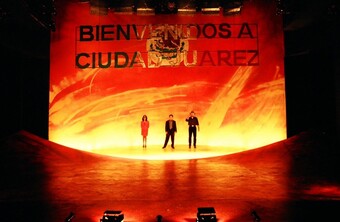

Well, so thought this glimmer-eyed postgraduate back in the salad days of 2014. Very quickly did I indeed grow bored. I moved back east, because apparently all the interesting theatre was happening in New York. It might have been, but I couldn’t afford a ticket. Back to Chicago. More of the same, but I found work and a sweet man, so I’m here. The best show I’ve seen in this town—by a fat margin—was a toured production of a fifty-year-old American chestnut as imagined by a fifty-year-old Belgian; a show which had already swept London and, mais bien sur, New York.

Let me get right to the point

I don’t pop my cork for every show I see, clearly. In a word: I’m against the New Play. New Plays take many forms and have been around for years, but they seem especially prized lately. They’re plays with budget-friendly cast sizes, simpler stories with watery stakes, forward-slashes to indicate overlapping, a pretty strict adherence to the fourth wall, “ordinary” unaffected language, and an authorial injunction to either “play it fast” or “respect the beats”—or both. Further, all of the matter onstage is matter of the theatre (i.e. no video, film, poetry, live musical interlude, non-diagetic dance, opera, or lip-sync).

How to spot a New Play from five hundred paces

The marketing copy reads something like:

[Main character] always thought she understood [thing]. But when [inciting incident occurs], she’s forced to question everything she ever knew. A [two or three blandly adulatory adjectives, usually some variation of “bold,” “penetrating,” or “funny”] new play that explores what happens when [condition a] turns into [condition b].

I am bored

This is conservative art. I’m not interested in it. It doesn’t work because the stakes are too low; it’s neither grand nor especially intimate, the only two virtues left for theatre anymore (though they are both essential to our survival, both as artists and citizens). It’s calculated to be endlessly replicable and sometimes even seem “important,” but all it really does is take up space that could be occupied by more exciting, vital, and theatrical work—as in work that understands why it is an act of live art and loves itself for that.

If we must have plays

they might sound like this:

A woman tries to feed her husband a fried drumstick. Dragons roam a flat earth. The last Black man in the whole entire world dies again. And again. Careening through memory and language, Parks explores and explodes archetypes of Black America with piercing insight and raucous comedy. A riotous theatrical event, The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World AKA the Negro Book of the Dead hums with the heartbeat of improvisational jazz.

That’s from Lileana Blain-Cruz’s 2016 production of the Suzan-Lori Parks play, directed for New York’s Signature Theatre.

I want live art that heals me, talks to me, reflects me for at least four minutes in an evening, and I want everybody else in the audience to get that too.

Here’s what’s wonderful about that copy:

- The first four sentences describe actions or conditions of the theatrical space, but don’t promise a linear narrative, the kind where human characters move through one of the two plots (“the hero takes a journey” or “a stranger comes to town”). Instead, we understand that the play will deal with action and image more than story, and that those actions will involve repetition, failure, and rebirth (“a woman tries to feed”; he “dies again. And again”).

- The middle of the copy helps us to understand that the subject is Black American archetypes, priming us to enjoy the play looking for that as the topic instead of trying to tease out a plot. It also piques our curiosity as to the elements of Parks’ fantasia—Why dragons? Why is the earth flat?

- It’s a “theatrical event.” They never call it a play.

- The blurb ends by talking about the form, not the content or the plot: the “event” “hums with the heartbeat of improvisational jazz.” While I can quibble with some of the language (hearts beat on the one and three, don’t they?), it’s nonetheless remarkable.

That’s a play, Mary. But what else could we have if we liberate ourselves from that word entirely?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Fantastic article. I love many new plays and playwrights - but I also know that theater needs to focus on the things it can do that can only happen in the moment of live performance. What are the experiences that can only be had if you (as an audience member) are there in the room, with other people? That may feel like a little sliver, but it's a little sliver of infinity. We have so much territory to work in, and yet so often put ourselves in a small box in terms of the forms of theatrical experience, walled in by more or less traditional narrative structure, by psychological recognizable characters, by safe conflicts and resolutions.

Thank you for the encouragement to bust out!

Well …. yes, there's a formula, I guess, for a play, as Rob writes. Character is in status; character has rug pulled out from them; character has to acknowledge a secret they'd rather not ever look at. But there is a formula for the kind of theatre Rob advocates for: dragons die on the stage while a violin plays and sparkles sprinkle and other things happen, physically and environmentally. That's a kind of formula. If the playwright and the community of performers risk--if they are writing or performing "their" impermissible, not the audience's--then I'm going to be in the audience and know that. That's what I want. Real risk from the playwright, from the performers, from the language, is what I want. I don't think I want preferences for one form of theatre over another.

Theatre flourished when playwrights were disposable and actors humbly lived at the bottom of the food chain. Today we are ruled by actors. "We" should dissociate with power and play from the dirt.

Disposable playwrights? Actors living humbly? If you think having 90+% of your Union working without a living wage while doing union work is not "humble," I'm afraid you and I have a different definition of that word. Yes, the dearth of excellent playwrighting/playsmithing is a problem. It always has been. Probably always will be. Especially for those with a "new" voice. And yes, some actors (read MOVIES, read TV) do make a living wage and then some, but not most - most certainly not most.

I have always been a bubble gum and baling wire theatre practitioner. If you must have more than two boards and a chair, the play/story/event/happening is lovely but certainly not necessary. I don't need a giant ape or a helicopter or any of those things to bring the essential to the space, to bring the audience to the space, and in that space bring them together to create something new, something whole, something alive.

People ruin their health and their lives trying to be working actors or playwrights. They don't ask for much. Just to be able to do what they have chosen to do with their lives and be able to have a little place to live, maybe a kid, possibly a lawn mower, or even a long-term relationship. But most of the people attempting these lives wind up paying to play or finding solace in things other than their original drug of choice, sharing the essential with others, and losing themselves completely.

Saying that actors need to be back down in the dirt is cruel. Saying that playwrights should be so plentiful that they are disposable is heartbreaking.

It isn't about dissociating from power. It is about finding the power within ourselves and using it - no matter what that means to you as an artist (go Broadway or go home? start the only live theatre space in 200 miles? refuse to allow norms to dictate vision?)

Brother, we are already in the dirt. We live here. We grow here. We thrive here. Come by sometime, and we'll show you around.

Thank you for articulating this so well, Rob! Now that TV is sophisticated, there is no reason to have a fourth wall in the theatre - why should anyone leave their large-home-screens to go to the theatre to have a wall placed before them? Theatre can do so much more in terms of ritual and ritualized space inclusive of its audience - the more we challenge the old models, the more necessary theatre will be.

Hi all! I'm not on Twitter, but the good folx at HowlRound have been keeping an eye out for what people have been saying about this little pamphlet we've published. I'd like to start a conversation with them here.

Our first caller says:

"This critic has some points on what's lacking in Chicago's 'house style,' but the notion that the type of theatre they want is impossible to find in Chicago beyone the odd big-budget transfer is so negligent. When theatres like First Floor and Haven and Red Tape and Sideshow and Free Street continue to push these boundaries with no acknowledgment, it seems much more helpful for a critic to boost their platform than complain about their perceived lack. This piece seems to describe Salonathon's weekly perfoqmfes to a T and then says that sort of thing doesn't exist in Chicago, and though it's gone it spawned so many successors (Will Davis's American theatre was the same way). And even if it's just spectacle he's looking for, some of our biggest companies (e.g. The House, Lookingglass) are known for delivering exactly that. This critic's piece on Taylor Mac changed the way I think about theatre criticism, but clearly someone needs to show him the full picture of where that exists in Chicago. It's harder to find than it should be, but that doesn't mean it's not there."

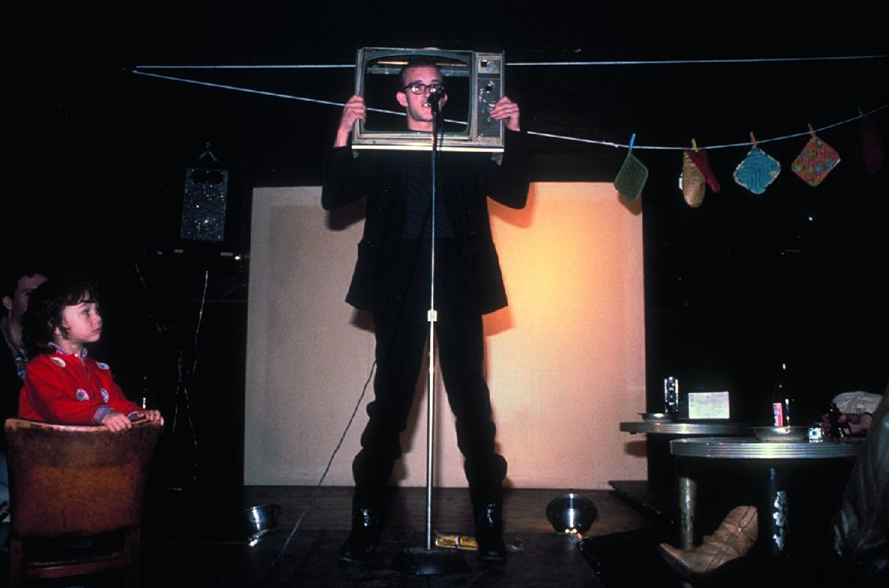

I'm so glad this has been articulated! As soon as this was published, I thought, "Oh yeah—totally forgot about Salonathon." (Which, admittedly, I was never able to make it out to—but, from everything I've heard, it's the closest thing to Club 57/Pyramid/Danceteria Chicago's had in the 21st century. RIP, tho.) What I most want to address here (and which I'd like to speak to with more nuance and less vituperation—which comes off as snobbish here, I know; sorry, folx—in a second version of this essay) is that Chicago contains multitudes, and there's a lot I haven't seen. Never seen a House show; seen two Lookingglass shows but neither were rooted in spectacle (Title & Deed and Life Sucks).

That said: the emotions from which I wrote this didn't arise from one or two boring shows. It accrued. The impetus for this essay was a bitter disappointment that I had gone from loving theatre to tolerating it, waiting for a wonderful show. And can I be honest? I've seen most shows alone. I don't know how much these down feelings would change if I had a guide who was REALLY excited to show what they loved with me—maybe you, caller.

There are companies—one example is About Face—which could be really leading the charge in their main seasons with queer work—and, like I jockey for up there, queer forms, not just gay people. I don't see that happening. And I'm just disappointed. That's the thing: there's so much happening in Chicago, so if it's happening, it's not being boosted in a way that's reaching me, a queen who's hungry for it. How do we change that?

I hope that some of my (emotional) generalizing didn't lead you to miss the rest of the piece. I'm much more interested in getting people to think about the why of fourth-wall-bound theatre than I am in grinding an ax about how Ivo van Hove only comes to town once every nine years. :)

And I'm so glad you loved that Taylor Mac, piece, caller. Let's keep talking about this!

__

And our second caller, from an unspecified city:

"We must be looking in different directions, or else one of us is determined not to see. The kind of new work this person wants is everywhere. It is heartbreaking to constantly be reading, seeing, and making this kind of hungry, desperate, joyful, ugly, lovely art to be told that it, we, don’t exist. Sorry, is our marketing not good enough? Or are we just not usually men, not usually white? Or because we’re usually poor?"

I think what you're saying suggests a line of inquiry I'd like to explore: if this work exists, it's not reaching me as easily as the 25 most visible theatres in Chicago, right? So how do we get the word out? I'm not on social media, but I am on the internet a lot. I read the local alternative weekly, Perform.ink. I'll pay $20 for anything that sounds interesting. How do we connect the people who want formally adventurous work to that work?

I love a good manifesto. This has Jones, Bogart, Parks, all wrapped up in it. Hear, hear! No boring plays!

Best article ever (this week :-)

You are giving me hope here in Paris (france) where the situation far more miserable than in Chicago! Political correctness (in state subsidised theaters), lack of money, lack of inspiration, lack of talent, (which all in all means mostly lack of guts) make this boredom feeling unbearable. You gave me the stamina to rebel against it and do something :-) Cool.