No Latinos Allowed

Dallas Mayor Re-imagines Art for Only 58 Percent of the City

The Dallas Series explores the challenges and rewards of creating theater in Big D. Join us this week as we journey deeper into the heart of Texas.

Growing up in a mostly white neighborhood in Dallas, the life lessons my father tried to teach me were very different than what my friends’ fathers taught them. What I remember most is when he would say, “You’re going to have to work harder than your friends to succeed because you’re Mexican.” When he said that, which was often, I didn’t believe him. I thought he was paranoid.

Not until I was twenty years old did I begin to sense my “otherness.” It was 1995 and I had chosen to become a professional actor but the lack of Hispanic roles in area productions was discouraging. If Teatro Dallas, the area’s only Latino theater at the time had not taken me under its wing, I probably would have given up within a few years.

Then, in the early part of the millennium, more opportunities started to open up. In 2002, the Shakespeare Festival of Dallas and Our Endeavors Theater Collective collaborated on Two Gentleman of Verona and cast me as one of the leads. I will never forget when a veteran Latino leaned towards me at the cast party and whispered, “This show was groundbreaking. I have never seen three Mexicans playing principal roles before at the Shakespeare Festival.”

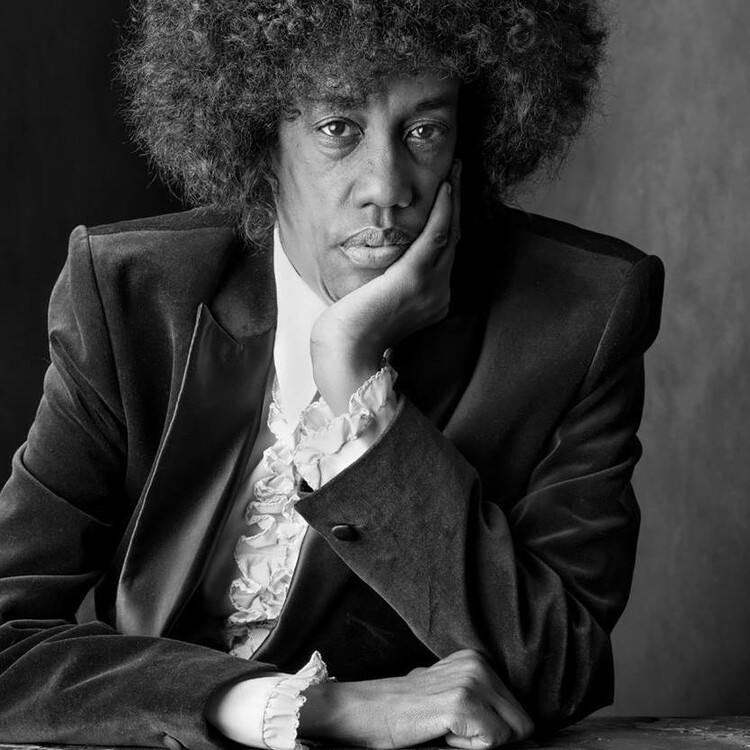

Fast forward to 2014 and I am involved in another groundbreaking project. My company, Cara Mía Theatre Co., is in the middle of a four-year collaboration to develop a new play with the Dallas Theater Center. As far as I know, North Texas’ only regional Lort theater has never before committed four years of time and resources to collaborate with a theater of color like ours.

Latino artists from my generation have benefited from unprecedented access. Thanks to the previous generation of Latinos such as Cora Cardona from Teatro Dallas who fought for greater funding for organizations of color from the city’s Office of Cultural Affairs, Cara Mía can boast today of quality city funding. Thanks to her and others who advocated for the creation of new public cultural centers, Cara Mía can also call the Latino Cultural Center our home theater. Furthermore, mainstream theaters like Shakespeare Dallas and the Dallas Theater Center have hired progressive artistic directors such as Raphael Perry and Kevin Moriarty who have opened doors to people like me. It is clear: Dallas is evolving and the city my father knew was very different from the Dallas I know.

Then, about one month ago, I received an email inviting me to attend a panel discussion entitled, “Re-Imagine Art in Dallas: A Creative Conversation with Mayor Mike Rawlings.” It is important to know that this is the only city-sponsored event during the year in which the Mayor specifically talks about the arts. Still, I was intrigued by the event’s title. In my view, Dallas is at a unique point in its cultural history. Within the arts community, we seem to share a collective vision that Dallas is becoming a world-class arts city and we often talk about how we are on the verge of a cultural renaissance.

However, when I read the list of speakers on the mayor’s panel, it was made of six women, including five artists and one critic. In terms of racial diversity, only one was African-American and another was from Iran. The rest were white speakers. Where was the Latina? Dallas is an astounding 42 percent Latino and the mayor is going to “Re-Imagine Art in Dallas” without including anyone to speak on our behalf?

After a campaign of emails and phone calls to the mayor’s office, a Latino (not a female) was added to the panel. In spite of the mayor’s backpedaling, it was clear: Latinos in general are not part of his vision for the city.

The more I thought about it, the more I wondered: Was the mayor’s initial omission an act of discrimination? If my father were alive today, I’m sure he would answer with an indignant “Yes!” My dad lived in Dallas during the Jim Crow laws, when signs outside of restaurants read, “No Mexicans and No Dogs Allowed.” He had to fight tooth and nail for upward mobility. Racism was part of his daily experience. Personally, I have never thought that I had been a victim of racism, but in this instance, I felt discriminated against. As a career advocate for Latino arts, I couldn’t help but think that the mayor was guilty of racial discrimination. Sure, he saved face by adding a Latino but if he had not been forced to backpedal, he would have blatantly disregarded 42 percent of our population.

This was very disappointing because I too feel that Dallas is on the verge of a renaissance. We have the artists and we have the wealth to make it happen but what is holding back our arts groups, especially our groups of color and our more independent companies, is that many of us don’t benefit from substantial support from the private and corporate sectors. Dallas is enormously wealthy and major institutions such as the Dallas Opera, The Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and the Dallas Theater Center enjoy tremendous financial contributions as well as board membership with connections to private wealth and corporations but groups like mine struggle to find access to financial sources.

Historically, groups of color throughout the country have struggled with this lack of access and we have seen many important theaters of color disappear due to a lack of private support. In Dallas, I believe that this problem is what keeps our collective arts community from reaching it’s true potential. As the city’s highest elected official, the mayor is the nexus between the public and private sectors and I thought he could be the person to unite the arts and the business communities.

During the initial backlash against the mayor’s office, I spoke with his assistant. I recommended to her that Mayor Rawlings create a task force to address the question of “re-imagining art in Dallas.” This task force could meet year-round and address questions of maximizing the impact of groups of color and the broad spectrum of independent artists. One of the key goals could be to connect the business and the arts communities in innovative ways. Unfortunately, the mayor’s assistant rejected my idea without even consulting him. I felt like my voice was not valued. I felt like an outsider.

It’s hard to believe that the mayor would blatantly discriminate against Latinos but his actions leave that possibility open. Considering our city’s history of discrimination, his actions are like vestiges of racism from another era. I know this: Our city still has a long way to go. Until we definitively cut our ties from Dallas’s history of exclusion, Dallas cannot become what we all envision it can be‑a world-class arts city. Even worse, until Latinos have an influential voice in our community, my father’s words will remain true: we will have to work harder than others to succeed because we are Latinos.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Hello David,

I'm interested in becoming involved in more social activism, and theatre. I'm of mixed ethnicities, African American and Hispanic. Does Cara Mia represent all colors, or is it mainly for Latinos/Latinas? Getting representation for my small, but growing, "mixed race", is an uphill battle, but considering I identify as Hispanic, I wanted your input.

I really enjoyed this article, thank you for calling out our cities shortcomings. Hope to hear back. Andrea

Cara Mia's mission is to reflect the experiences of Latinos in the United States and it is important for us to make sure that the Latino community receives cultural and artistic opportunities. However, our company is made up of people of all colors and nationalities. We are black, white, brown, Mexican, Brazilian, Peruvian, Chicano... To get involved, please go to our website for information.

With all of this 're-imagining' you would have

thought that they would have imagined to include all groups... and I'm

not saying this because they had to have a black person, a white person,

an Asian and a Latino (this was not a United Nations'

meeting); but because arts is about seeing everything from different

perspectives, and mostly because it is part of becoming a person (in

this case a city) of culture to get acquainted with other CULTURES. And I agree with Clyde.. we shall create our own Task Force and take it to City Hall meetings,

Great Article David! looking forward to working together with all of you and creating our city they way it should be!

Hi All. Great thread, thanks to David for stirring things up. Idea: How can we maximize our voice at the Dallas Faces Race Conference in November http://dallasfacesrace.com/... Who has been to this event? Cora Cardona just forwarded me the link, and I know she has been involved. I just found out about it. Also, the significant Asian population in Dallas is largely invisible in most cultural discussions. How might we be able to link up with them also?

David,

As a new member of the creative community here in Dallas, I appreciate you stepping up to point out the blind spot of this particular event. I also think the idea of a Task Force doesn't need the mayor's permission, endorsement or support. We are all citizens and we can all freely gather to discuss our own ideas around building a stronger city and pushing culture forward in ways that benefit a wider group of Dallasites.

I appreciate the thread here and look forward to the work ahead for all of us that want to see a more just and equitable city. And it starts with imagination, inspiration and leading by example. I see you and many others doing that for Dallas David. Respect.

Lauren Smart at the Dallas Observer wrote an entertaining blog piece about this as well.

http://blogs.dallasobserver...

These groups desperately need to be representative of the population at large, not just who has the money.

Dallas is a great place to begin ambitious initiatives to give voice to many different artists and arts groups because we have the human capital and we have the wealth. What is there to lose? There seem to be only tremendous gains for the city if we act.

I whole-heartedly agree. I would love to get together an annual 24 hour play festival or something similar to get local playwrights, directors, and actors all more opportunities to generate new work and work together. Lets make new projects!

Lets start putting our heads together.

Hey Kyle! In addition to your idea, which I think should be an outdoors play festival at the new Klyde Warren Park on the deck (that will show the powers that be the STRENGTH of our collective community!), we have to address the glaring shortage of available spaces in which to showcase our work. Whether it is an incubator program for emerging playwrights, staged readings or full productions, we have to have SPACE to do this CONTINUOUSLY. I have an idea for making this happen and it doesn't have to cost the City one red cent. I'm sure we'll all be talking soon because I feel some type of monumental shift occurring and that's good! :-)

David, while reading your op-ed, I have to admit that I burst out LAUGHING when I got to the part where you described the make-up of the forum panel. Why? Because you seemed as disgusted as I did when I attended last years event and it was all white men (except for the courageous white sister who crashed the stage without a formal invitation and began talking). I wrote about the event for Examiner:

http://www.examiner.com/art...

After I finished reading, it is super CLEAR that both of us understand what needs to happen here. And I love your idea of a task force formed to address this issue and report its recommendations to the mayor and city council. I'm going to call you tonight to discuss this further. Keep your chin up; we will win this battle :-)

Thanks Buster. I look forward to hearing from you. I think we have a great opportunity ahead of us if people choose to act. I think people can realize that the arts sector is a viable industry as well as a cultural service in Dallas. There are too many people with skins in the game who have made professional careers here. Artists also benefit from communities of patrons who support what we do. We don't have to be helpless. I believe we have leverage if we exercise it.

David, missed you last night. With all of the thunderstorms and rain, my pooches were pretty antsy when I got home so I had to give them my undivided attention/love. I will call you this weekend!

Thanks for your insight, David. You're right- there is still a lot of work to be done, and I hope this article is being passed along to people in power who can help...