Interview with Marcus Gardley

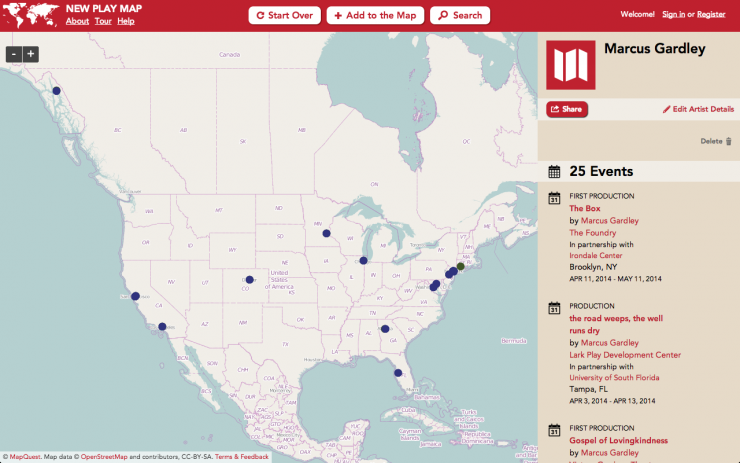

Marcus Gardley, a thirty-six-year old, award-winning playwright-poet, is making a substantial impact on the national performing arts community. Within the last year alone, theatre companies, ranging from Brooklyn to Denver, have performed Gardley’s works (including The Box at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn, in a Foundry Theatre production, Black Odyssey at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, The House That Will Not Stand by the Yale Repertory Theatre, dance of the holy ghost: a play on memory by Center Stage Baltimore, and The Gospel of Lovingkindness at the Victory Gardens Theater in Chicago).

Gardley’s plays often contain similar features. For instance, his poetic lyricism (combining poetry with music) appears in both Black Odyssey and On the Levee, enhancing the characters’ emotional expressions through musical embodiments and often creating a dichotomy between the past (using old text) and the present (employing contemporary tunes).

Gardley is also known for tackling complex subject matter. Gardley, himself, states, “I can’t tell a story if there isn’t a political point…I’m an activist.” His play The Gospel of Lovingkindness, whose world premiere was February 28, 2014, at the Victory Gardens Theater, embraces Gardley’s poetic lyricism and controversial themes. Set in Chicago, the play depicts two mothers who meet for the first time. One mother’s son is achieving his goals; the other mother’s son is struggling. What happens when the mothers’ stories collide? The play approaches topics concerning societal structures in South Side Chicago and gun violence.

HowlRound’s Chicago Commons Producer Rebecca Stevens recently interviewed Marcus Gardley, discussing his motivations, struggles, and inspirations behind “The Gospel of Lovingkindness” as well as working in Chicago.

Rebecca Stevens: How did you first decide to work on The Gospel of Lovingkindness?

Marcus Gardley: I’ve always wanted to write about the South Side of Chicago. But Chay [Yew, artistic director of Victory Gardens] actually had an idea to write about the LGBTQ ball scene that grew up out of the South Side of Chicago. I spent four months talking to people about the ball scene with people who didn’t really want to talk. Somebody finally hunted me down—he was a head of a ball house—and he said to me, “You know, it’s hard to talk about this stuff when our kids are going to the balls and they run the risk of being shot.” And it just hit me like a lightening bolt, and I thought, “Oh yeah, what about gun violence? How did I miss that? How can I weave that into this story?” We realized we have to talk about what’s current. This is something that everybody needs and wants to talk about, and this is a great platform to do that.

For about a year, I interviewed people on the South Side, and I’ll never forget my first experience. Not knowing anything and not doing enough local research about who to talk to and how to get there, I took a cab from the North Side, from Lincoln Park. I said, “I need to go to Pilsen,” but the cab driver wouldn’t take me. In fact, he took me up until I got to Pilsen. I said, “Well, this isn’t the address.” And he said, “I’m not going there.” And this was during the day. He said, “I’m not going further than this.” And then he said, “Do you know what you are getting into?” So I called 311 and long story short, the lady on the phone talked to the cab driver and then she said to me, “Sir, you are going to have this problem because the cabs don’t really go down that far.” And I said, “It’s the day time!” And she said, “It doesn’t matter.” And so he charged me half the cab fare and then I really had to walk the rest of the way. And that’s part of a series of conversations about how people are perceived who live in a different part of town.

Rebecca: As an outsider to the South Side, how did you integrate yourself into the community? What was it like to work with collaborators who had many experiences of being in Chicago to draw from?

Marcus: I always preface an interview by saying, “You own your story, I will never take your story and rewrite it. In fact, I will never put any major aspect of your story into the piece, so that you always own your story.” I’ve been doing this for ten years, and this was the first community where people said to me, “Oh no, I want you to tell my story.” That was powerful. “I want you to tell it, you can even use my name.” But while people wanted me to tell their story, but they also want me to get it right, detail by detail. I had a great cast. This cast really challenged me, down to the comma, is the way I always describe it. “This doesn’t make sense, this is not what we call Daley Plaza, we are actually not obsessed with pizza.” The cast all lives on the South Side—everybody but one actor—they all live there, and they all made a conscious choice that they were going to stay on the South Side. They wanted the people in their neighborhood to know that 1) you can be an artist and make it, and 2) that we’re not going to run, we’re not going to live in fear. That had a huge impact on making the piece. I don’t think I’ve ever been this nervous about writing about a community, because in the past I had some kind of root connection to the community. But in Chicago mostly everything was foreign to me, and I felt like I had to nail it, I had to get this right. These people were going to be honest and tell me, “that’s bullshit.” So I really worked my ass off on getting it right. And it was a very powerful experience.

Rebecca: How did you know that it was right? What kind of feedback did you get from audiences?

Marcus: We had a series of talkbacks where we had a large group of people from Englewood come, and they had never seen a play before. After the play—and these were young people—they were stunned into silence. Then they didn’t want to leave because they had so much to talk about. Their bus was honking outside for them. I felt honored that they were moved, and the comment I kept getting back from them was, “that was real.” A lady left screaming, “It was real! It was real!”

The next day, we brought some African-American women who were part of a club from the North Side. They loved the play, but they felt like the use of the n-word was gratuitous. And so they couldn’t engage; all they wanted to talk about was the n-word. Then somebody in the audience, said to them, “We are focusing on this word because if we focus on the word we know we can’t fix that. But focusing on the problem? That we can actually fix, but it feels too big, so we focus on a word.” And the two women got into a really heated debate. It was very, very tense. I’ll never forget, one woman said, “The young boy was too articulate. No young person from that neighborhood would have access to that kind of language.” And they were all African Americans, but here was the divide—it’s a class divide now. So for me, I write because I want people to have a conversation. I feel like that’s the power of theatre; it sparks a dialogue. Here two people who live on two sides of a border who are now having to look at both each other and themselves. I felt like if the play is doing that then it’s doing something in the world.

Rebecca: What did you rely on from your past experiences working with and writing about communities? What shifted in this a community where you felt more like an outsider?

Marcus: What shifted is that I can never be an authority on my subject matter. Most of the people I talked to, not only did they live in Chicago, they were born in Chicago. One of the actors described it by saying, to live in Chicago is to live with an open wound. Because there are so many deaths and people live with this as a daily occurrence. It’s different than any other place in the country. The complexity of what’s going on in Chicago means you can’t be an authority on that complexity in a year, in two years, in five years, because it has levels and layers. Some of the interviews were just spilling out of tears and release. No one ever asked them about how they dealt with their grief. I never was an authority, I was a listener. I’ve never had that experience before—I’m listening and trying to be open to the process.

Rebecca: Chicago’s North Side and South Side are distinct in just about every way. The two sides of the city are geographically distant, segregated, and have large disparities in their distribution of resources and opportunities. What’s it like to be bringing such an important part of the South Side into this epitome of North Side cultural life?

Marcus: It was my big desire for the piece to bring communities from the South Side into see the play. We wanted to engage both communities, for them to watch the piece together, but the excitement from members of the South Side was so large that they would usually just take up the whole house. After opening, it was most predominately people from the North Side and then the people from the South Side did not come because, of course, we didn’t have funding to keep busing groups in. What was amazing about those few weeks where we did bus people in was that they started to talk to each other, and they started to merge their coalitions. The most profound comment that I got from the majority of people was that no one talks about the aftereffects when someone dies. All of our stories are about what led up to the shootings. What moved them the most was that this was about after the murder and how people deal with grief. They came with their chest up, thinking, “What is this?” and they were shocked. So I was very honored by that.

The most profound comment that I got from the majority of people was that no one talks about the aftereffects when someone dies.

Rebecca: In the shows that I watched and the talkbacks I participated in, a lot of audiences from the South Side were witnessing the experience on stage and naming it as their own, saying, “Yes, this is what we see.” A lot of the older, white audience members were focused on trying to solve the problem. How do you feel that one’s personal distance from the events shifts how they experience the play? What are the differences between bearing witness to a story and feeling compelled by a story to change the circumstances in which it happened?

Marcus: I feel like for African-American people from these communities in particular—and of course we’re generalizing—witnessing is where they are, because for them it’s like, “Finally this is what we’ve been saying. It’s been given voice.” They’re living with it. Being heard and having it spoken back to you, is huge, revolutionary. For a lot of older white audiences, their response is, “What can we do?” Because, for them, that is what the play is asking them to do. That in itself is revolutionary. But the play is asking everyone to do it, it’s all a matter of where you are. And both of those things are valid and have equal weight. I love that question because to me when you start getting questions like that you can actually see how the work is doing something. Because if the black people can hear that the white people are actually interested in doing something, and the white people can hear that the black people are witnessing and that’s also a form of revolution, if you put those together, that’s a great start. That can create great change, as opposed to, “Look at how different we are.”

Rebecca: How does it feel to have Chicago playing such a large role in your life? How is it shifting you?

Marcus: I’ve always wanted to have a theatre home, very much in the model of Shakespeare where you have one place, you have a group of actors, and you write for a city. I’m a homebody. I like to be in one place and sit for awhile and take it all in. I think that for me to survive up until this point I’ve had to take gigs wherever they were. I’m looking forward to resting at a specific location for awhile and really both learning and giving back to the city. I’ve always wanted to write about Oakland, because that’s where I’m born and raised. There are no theatres in Oakland, it’s a protest town. There’s a lot of revolutionaries and progressives there and they are doing a lot of great work. But what Chicago offers me is the love I’ve always wanted to tell about my own city where I grew up. It feels the same but also it challenges me to get outside my own experience. It’s making me a better writer because I can’t rely on my old tricks. I have to engage people, I have to run the risk of not being well received. Chicago’s so diverse, everybody’s so different—there’s class, there’s race, there’s sexual identity, faith and religion—all of these things play into who you are talking to, so I couldn’t rely on any of my old tricks as a community person or an interviewer or a playwright. It’s challenging me and also forcing me to grow as a writer. All to say that I’m really excited about this opportunity. So far it’s been phenomenal.

Marcus Gardley’s works, such as The Gospel of Lovingkindness, are gaining national prominence, attracting audiences of various ages and backgrounds. By combining music, poetry, and political commentary, each play deeply affects viewers, evoking assorted emotions and reflections.

***

Additional research contributed by Molly Reinganum.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Bravo Marcus. And great piece, Rebecca. I love the thought that a residency can build courage in a writer- because when simply practicing your craft and hustling for gigs isn't overwhelmingly hard, there's a chance to go deep-- with the work; with your collaborators; with the community.

I so want to see tis play.

Bravo Mellon Foundation too. We should have resident playwrights in every theatre in the country- for reasons above; and for what our great writers with home theatres, like Marcus and Aditi Kapil, are demonstrating as possible.

Marcus, I found this piece fascinating, and I wish I had seen the piece. It's interesting that sometimes critique quiets debate and so people thingk 'Oh, I had better take that out.' But here you are saying: 'I write because I want people to have a conversation. I feel like that’s the power of theater; it sparks a dialogue. Here two people who live on two sides of a border who are now having to look at both each other and themselves. I felt like if the play is doing that then it’s doing something in the world.' bravo.