Encuentro 2014

Moving Forward, Never Forgetting the Past

The Encuentro 2014, National Latina/o Theater Festival opened at the Los Angeles Theatre Center on October 16, 2014, in a red carpet affair that gave credence to the term, “We’ve come a long way, baby!” Audiences are delighting in the productions from the Four Corners and Puerto Rico, as well as listening and learning from the participants in the Tertulia events: informal conversations that widen the scope of the discussions in the lobby. There is a palpable awe and appreciation for the diversity of the productions and the variety of the companies (nineteen total) in residence. For most of the audience members as well as the participating company members, this is probably their first exposure to such an event, especially of this type of Latina/o theatre and performance.

This is a historic and life-changing event that few people realize has its precedents in the annals of Chicana/o theatre history. A theatre festival is the natural manifestation of the collective desire to celebrate a people’s history, myths, hopes, and dreams; to share ideas and quite simply to be renewed in one’s mission as cultural workers. In the case of Latina/o theatre, there is also the desire to question the status-quo. In this piece I would like to share a little about the precedents that led to this historic, month-long event, focusing on the evolution of Chicana/o theatre festivals since 1970.

A theatre festival is the natural manifestation of the collective desire to celebrate a people’s history, myths, hopes, and dreams; to share ideas and quite simply to be renewed in one’s mission as cultural workers. In the case of Latina/o theatre, there is also the desire to question the status-quo.

In 1968 El Teatro Campesino joined Bread and Puppet Theater and the San Francisco Mime Troupe as performers and participants in the Radical Theater Festival, hosted by San Francisco State College. This festival was not a competition, but rather, a sharing of ideas by the directors and members of the three troupes—all dedicated to social justice. The following year, El Teatro Campesino traveled to Nancy, France to perform in Théâtre des Nations—an important introduction to the festival process and to the wide variety of international performing troupes. The members of the still-fledgling farm worker’s theatre presented their agit-prop actos (sketches) and protest songs in the midst of world-class theatre companies. It was politics vs. art and El Teatro Campesino members held their own—performing what I have termed “Necessary Theater” for enthusiastic audiences who appreciated their working-class status and the message of hope for all farm workers of the United States.

Back in the US, El Teatro Campesino had been encouraging Chicanas and Chicanos, mostly university students, to form their own teatros. Théâtre des Nations inspired Luis Valdez and members of El Teatro Campesino to host the First Chicano Theater Festival in Fresno, California in 1970. There were approximately fifteen troupes participating, most composed of theatrically inexperienced activists. Valdez knew that these incipient teatristas (theatre workers), more interested in politics than aesthetics, needed guidance in how to successfully promote social justice through political theatre. Thus, a festival was formed to assess the needs of the Chicano Theater Movement, which was on the rise. Quite simply, the goal was to encourage the growth of participating troupes; to ascertain what other teatristas were saying, and to figure out how the leading teatro and its members could assist in their evolution.

With the success of the first festival under their belts, the Campesino members organized the Second Chicano Theater Festival, hosted by the University of California, Santa Cruz and El Teatro Campesino in 1971. Many more teatros participated this time, and it was clear that there was a need for a national organization to facilitate better communication between groups, and also to foster annual festivals and workshops. The late Mariano Leyva, director of the Mexican student group Los Mascarones (The Maskers), suggested the name “TENAZ,” which translates as “tenacious” and is the acronym of El Teatro Nacional de Aztlán (The National Theater of Aztlán)—Aztlán being the land to the north, the mythical home of the Aztecs.

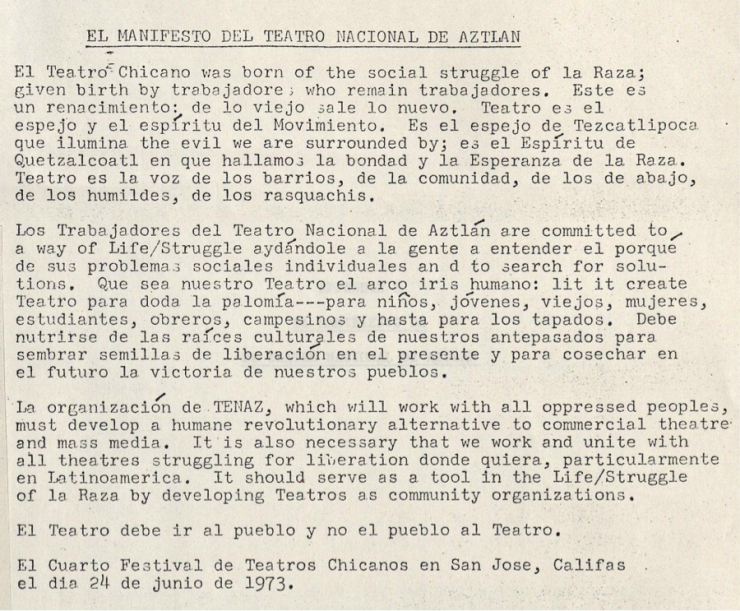

The third festival was held in Santa Ana, California and in 1973 TENAZ and El Teatro de la Gente (The Theater of the People) organized the Fourth Chicano Theater Festival in San Jose, California. As in previous festivals, there were workshops in all manner of theatre practice including mask making, dance forms, music, improvisation, and playwriting. Every morning representatives from four different groups sat on panels to discuss the previous evening’s performances. For some, the critiques were too critical; others took their notes and returned to their respective communities and campuses with a renewed vigor and determination to bring about social change. It was at this festival that leaders created the TENAZ Manifesto, which stated “The organization of TENAZ, which will work with all oppressed peoples, must develop a humane revolutionary alternative to commercial theatre and mass media.” Aesthetics were not discussed in the Manifesto; the struggle for social justice still prevailed.

There were over fifty groups represented at the fourth festival; groups and individuals came from San Diego, New York, Puerto Rico, Seattle, and many points in-between. The fourth festival became the predecessor to the most ambitious festival to that date: El Quinto Festival de los Teatros Chicanos: Primer Encuentro Latinoamericano (The Fifth Chicano Theater Festival: First Latin American Encounter,) organized by TENAZ, and hosted by C.L.E.T.A. (Centro Libre de Experimentacíon Teatral y Artistica, the Free Center of Theatrical and Artistic Experimentation) and Los Mascarones. This massive undertaking began with ceremonies and performances at the pyramids of Teotihuacán, outside México City and culminated two weeks later at the pyramids of Tajín, in Veracruz, México. The capital city served as the host to an array of performances, workshops, and panels that were held at several different venues. Many of the Chicanas/os had never been to México City, and their limited Spanish sometimes kept them from fully expressing their observations and feelings. It was a culture clash of major proportions as the working-class teatro members were exposed to, and contrasted with, major theatre companies and internationally known Latin American directors, and playwrights. Many of the Mexican, Central, South, and Latin Americans were fascinated by the Chicanas/os living en la barriga del monstruo (In the belly of the monster) in the United States, while said “monster” was running rampant in their countries—supporting repression and violence of all kinds in order to support American interests. We learned a great deal from that festival and all involved did, too; impressed by the fact that Chicanos were aware of all-encompassing North American problems.

At the festival, the participants were exposed to professionally trained theatre artists; people like Augusto Boal, Enrique Buenaventura, Santiago García and others who eventually became collective role models: Their politics were solidly in support of a people’s revolution, and their productions were eye-opening examples of what great theatre can accomplish. Political theatre, we learned, could and should be entertaining and educational. Many of us returned to our respective communities with a renewed respect for aesthetics. Some people continued to work with their teatros, others moved on to found other troupes, and by the early 1980s, more and more people entered the academies for formal training in the theatre arts.

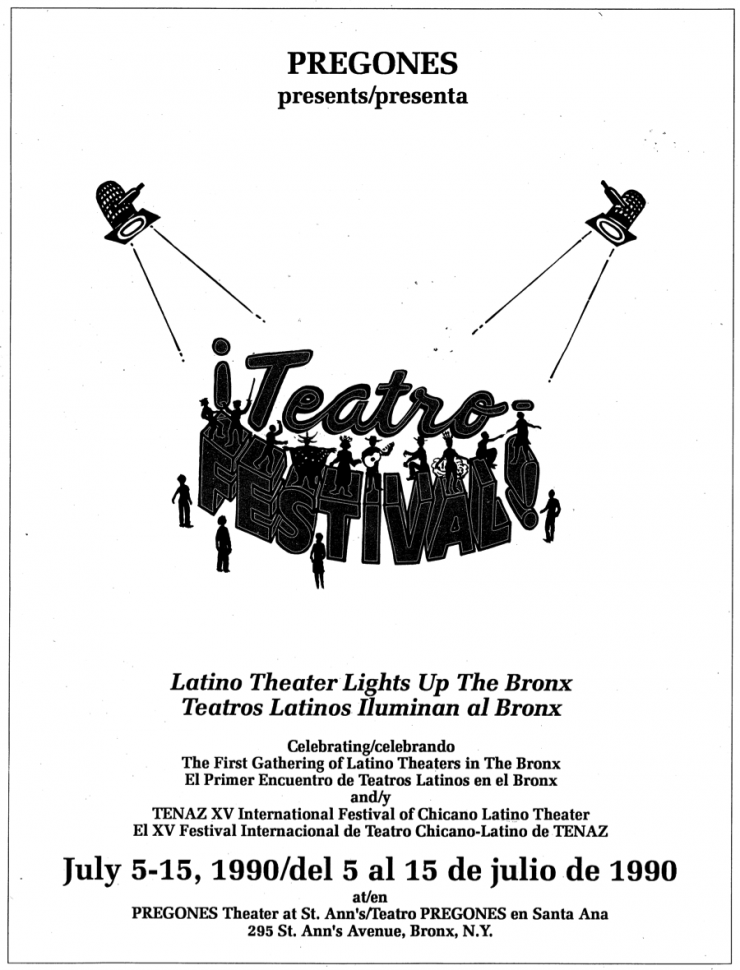

Other major Latina/o theatre festivals occurred in the following years, including the Festival Latino, sponsored by the New York Shakespeare Festival and Co-Directed by Oscar Ciccone and Cecelia Vega, in the 1980s and the International Hispanic Theater Festival, founded twenty-nine years ago by Mario Ernesto Sánchez and the Teatro Avante, of Miami, Florida, and which continues to this day. However, both festivals feature(d) Latin American and Iberian theatre companies. TENAZ festivals continued all over the country in various manifestations. In 1990 Rosalba Rolón, Artistic Director of the Pregones Theater, invited some Chicana/o troupes to their festival in the South Bronx (see the program here) and in 1993, the fifteenth and final TENAZ festival was hosted by Pregones (see the program here), but none matched the rigor of the fifth festival that became commonly known as the Mexican encounter. Because of that festival, Chicana/o theatre would never be the same.

Everybody is learning: from the artists to the scholars and especially the audiences. Latina/o theatre can no longer remain invisible, nor will it.

And now we jump forward forty years to the Encuentro 2014; where fifteen groups perform in five theatre spaces in a five-story building that used to be a bank. A bank that was built when banks were erected to give the patrons confidence that the building would not crumble as they did in 1929. And confidence is what this Encuentro is all about. When José Luis Valenzuela, Artistic Director of the Latino Theater Company at the Los Angeles Theatre Center, told me two years ago that he envisioned a month-long festival with company members committed to living in Los Angeles while performing, I didn’t know what to say. He also envisioned the participating company members as being divided or grouped with other company members—directors, actors, designers, producers—working together, devising pieces that would be showcased at the end of the month. I thought he was crazy. But the man was confident that it would happen and he, alongside the Latina/o Theatre Commons Steering Committee, HowlRound, and others, collectively raised the funds to make it happen.

The devising groups are working together; total strangers two weeks ago are now devising works that will demonstrate collective efforts—just as we did in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. The difference is that these people are not only student activists but (mostly) young adults and other veterans of the Chicano Theater Movement as well as professionally trained theatre artists. Some are first-generation North Americans; others are descendants of immigrants. They are representatives of many different countries, people of all ethnicities working together to create meaning out of the chaos of today’s world. Unlike the earliest TENAZ festivals, the artists are housed in hotels and enjoying the knowledge that they are “home” at the Los Angeles Theater Center: Esta es su casa.

Few Latina/o theatre companies in this country have the facilities, staff, and support that the Latino Theater Company members have, which they have worked over thirty years to attain. Their years of creating an ensemble of professional theatre artists as well as their commitment to their community(ies) is having a national impact through this festival. Everybody is learning: from the artists to the scholars and especially the audiences. Latina/o theatre can no longer remain invisible, nor will it. Every one of the artists and scholars involved will return to their respective companies, universities, and communities with a renewed sense of purpose. We continue to learn from one another in the tradition of the earliest festivals; the times have changed, the technology has changed, but the people remain people and the future of Latina/o theatre is in very good hands.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Mil gracias, Jorge. So important.

My High school Chicano Literature class has been studying teatro during the festival. Students wrote a play on the historic Denver, Co. walk outs 3-2-69. I directed another high school teatro for Escuela Tlatelolco Teatro Pachuco.

Bones Rodriguez C/S.

Thanks so much for this great information. Jorge. I'll share it with the Colectivo Teatral Nuevo México and with the National Hispanic Cultural Center, whose Siembra: Latino Theatre Festival is in full swing with the third production, Quiara Alegría Hudes' 26 Miles, opening this week, produced by Camino Real Productions.

Thanks for sharing such a great and concise history of Teatro festivals. Looking forward to seeing history be made in LA next weekend. Adelante!