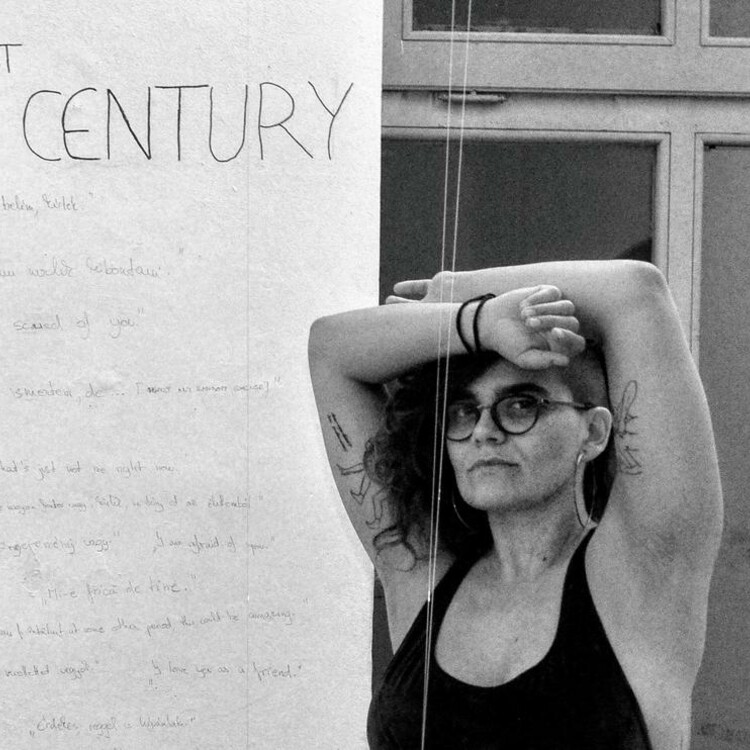

From Emerging Actor to Independent Artist / Pályakezdő színészből független alkotóvá válni

There is a picture that had been presented to the outside world from Budapest, Hungary for the past five years: a professional scene whose resources became limited due to governmental changes; carriers and works of art being ended for political reasons; artistic freedom and free speech being harmed. And there are several voices, a canon, who were presented in this context: Árpád Schilling, Kornél Mundruczó, Béla Pintér, Róbert Alföldi, and others.

The questions we would like to ask and debate in this series are: who are those who were already on the periphery before all this happened, and where are they now? How do they see this aforementioned picture, and what did it bring for them? What else is there to say or do; what tools are we giving to the next generation this way? The founders of the Dollar Daddy's both come from the University of Kaposvár, a theatre school that is in a small city in the south of Hungary. In their article they present to us their path from the countryside to the very heart of the capital.—Zenkő Bogdán, series curator

The following text was translated from Hungarian by Panna Adorjáni.

This is a new type of acting, the blend of subjectivity and character development is not “acting,” but “plain” existence on stage, I can hardly describe it. It advances lightly with an easy energy, without any dramatic outbursts. Just like an everyday conversation, what lies below the surface is always more compelling. For some, this feels significantly natural, [while] others will be more like actors, like a surface. And with some, this will also fit their characters. In these scenes that [are] on the verge of fiction and reality, reality is heavier; it is the unknown, the one that unfolds in the here and now. As if they would be saying improvised, unlearnt texts, as if they would only know the context, not these hesitant, spontaneous texts, born on the stage. This is then the new form, dollardaddy’s trademark style: being civil, quotidian, undramatic, and unarched. —Andrea Tompa’s review in Magyar Narancs

The concept of the old and the new are not as palpable in practice. Contemporary actor training prepares you for the same theatre work that actors have been doing sixty, seventy, or even one hundred years ago.

Although less and less young people go to the theatre in Hungary nowadays, many theatres have superficial solutions to this problem. For example, their youth programs are aimed for and represent those who are already involved. Because of the overwhelming number of applicants, obtaining an acting diploma is as hard to get nowadays as it was ten or twenty years ago.

Currently they are two higher education institutions offering acting diplomas: one in Budapest and one in Kaposvár. The university from the capital is a prestigious institution with a long tradition and an extensive network, while the one from the countryside is a new institution over ten years old with almost no traditions or strategies. This second institution was initially funded for the prospect of a new type of actor training, and in opposition to the Budapest institution. I graduated from the latter university in the summer of 2009.

The concept of the old and the new are not as palpable in practice. Contemporary actor training prepares you for the same theatre work that actors have been doing sixty-seventy or even one hundred years ago. Simply put, you are taught what you should do in a rigid theatrical hierarchy: how to operate and how to meet expectations to become successful. A basic problem is that many actors are not regarded as thinking people, but performers who constantly submit themselves without hesitation to the will of the director, an artist that stands high above them in this hierarchy.

There is a well-known theatre anecdote in Hungary: at the application exam, prospective students are asked to find their way to the top of the chandelier in the room. Whoever asks why they should do that will be the dramaturg; whoever starts planning and figuring out possible solutions will be the director; and whoever will just do it—well, they will be the actors. This is all very true, but the system has changed a great deal. Today, not all of us are satisfied with the label on our diplomas. The way my generation thinks is entirely different from the mind set of my “elders.” I tend to think that we are more distanced, more capable to reflect on our situation and work. We are a different type of fanatics, ones who don’t believe that their work is indispensable, and we don’t even think theatre is indispensable. There is a market for our performances, which are products we have to sell.

This change is also visible in the sense that emerging artists typically do not rely on state funding. These government funding regulations mandate that new companies are not eligible for operational grants for their first three years; thus, they are forced to work project-to-project without seeing through steps moving forward. This condition makes it harder to survive in the industry because long-term planning is impossible and you become endlessly defenceless.

The only solution is to find your own way and style. The Trafó House of Contemporary Arts was of great help for us in this respect; since 2013, dollardaddy’s has produced at least one production in their venues every season. It is here where we performed our Family Trilogy, which is based on plays by Ibsen and Strindberg, Rehearsal for the Eyes Wide Shut, and Chekhov—an adaptation of almost all of the author’s works.

In our performances we always remix classic works, such as Ibsen, Strindberg, and Flaubert. Our rehearsal processes start with an uncommon practice—four weeks of analysis and readings.

We first started producing dollardaddy’s performances in Budapest apartments while in university. One could watch these productions in a one-room apartment. A full house consisted of three actors and a maximum of six spectators. We all sat around a table, which was how the play unfolded. The first production that gained wide recognition and drew from this format was Bring Ibsen into my living room! (Hedda Gabler). For this performance, anyone could order the piece from their home, and we would take the performance to the kind viewers who invited us into their homes. It is a performance with three actors that can be put on just about anywhere. The idea was that we pretended to be the ones living in our viewers’ houses, and imagined our hosts as our visitors. For this work, we started examining the possibility of mixing reality and fiction together. The piece became quite popular and we performed it in over 200 apartments. With this piece, we also started experimenting with our company’s style, particularly the nature and quality of the acting that has become the trademark of our performances.

Dollardaddy’s main interest is the actor and their personality. We don’t believe in transformation, or the idea of the chameleon actor. In each of our rehearsal processes, we try to find the commonalities between the actor and their character. As a director, I am only interested in the solutions that an actor will offer me in a certain situation.

In our performances we always remix classic works, such as Ibsen, Strindberg, and Flaubert. Our rehearsal processes start with an uncommon practice—four weeks of analysis and readings. At this stage, our creative team works with the actors to analyze the text until it truly becomes their own. The actors contribute to the creative process by rephrasing and rewriting the text. I always arrive with a text that is already heavily rewritten and edited down, but this only serves as a starting point, a sketch for our performance.

We only leave the table when entering the performing space makes sense. For instance, actors already know the text by heart and want to start focusing on their movement and their presence. As a director, I am never interested in one line getting uttered in the space—our viewers always sit in a circle anyway. I’m more interested when an actor is honest and can fully represent their character. When a rehearsal process is successful, the actor does not make mistakes, and they do not forget their lines because they are expressing the thoughts behind it. Thanks to this, actors always have the opportunity—if they feel the need—to go off script, to leave out something, or to stay longer in a certain situation. This degree of trust can only be built through hard, but constructive work.

I am extremely interested to find out whether my generation, people in their twenties and thirties, will be able to renew theatre. Or will all their initiatives remain exotic experiments, while we all slowly melt into the already existing structure? I remain optimistic.

***

Az elmúlt öt évben kialakult egy kép a külvilágban Budapestről, Magyarországról: egy, a kormányváltás miatt egyre korlátozottabb forrásokból létező szakmai közeg; politikai okok miatt megszűnő szervezetek és félbemaradó művészeti alkotások; a szólás és alkotói szabadság folyamatos megsértése. És ebben a kontextusban megszólalt több hang, egy kánon: Schilling Árpád, Mundruczó Kornél, Pintér Béla, Alföldi Róbert stb.

Kik azok, akik mindezek előtt is a periférián voltak és hol vannak most? Hogyan látják ők a fentiekben leírt helyzetet és mit hozott számukra? Mit lehet még mondani vagy tenni? Milyen eszközöket adunk a jövő generáció kezébe ily módón? - ezek a kérdések, amelyeket fel szeretnénk tenni és megvitatni ebben a sorozatban. A Dollár Papa Gyermekei alapító tagjai a kaposvári színművészeti egyetemről jöttek, egy Magyarország déli részén fekvő kisvárosból. Írásukban leírják a vidékről a főváros szívébe vezető útjukat.—Zenkő Bogdán

„Újfajta színészet ez, a személyesség és a karakterképzés elegye, nem »eljátszás«, hanem »sima« lét, színpadi létezés, leírni is nehéz. Könnyű, kiengedett energiával halad előre, különösebb drámai pukkanások nélkül. Nagyjából amilyen egy mindennapi beszélgetés: a felszín alatti az erősebb. Van, akinek ez kiemelkedően természetesen megy, lesz, akiben több a színészet és a felszín. És lesz, akinek a szerepéhez ez jól is áll. A fikció és valóság határán egyensúlyozó jelenetekben a valóság a súlyosabb, az ismeretlen, az itt és most feltárulkozó. Olyan, mintha meg nem tanult, improvizált szöveget mondanának, csak a szituációt ismernék, nem a mondatokat, amelyek akadoznak, spontának, a helyszínen születnek. Ez volna tehát az új forma, a Dollár Papa társulat saját védjegye, a civilség, mindennapiság, drámaiatlanság, ívtelenség.”

(Tompa Andrea cikke a Magyar Narancsban)

Annak ellenére, hogy egyre kevesebb fiatal jár színházba Magyarországon, a színházak pedig csak látszatmegoldásokkal próbálják palástolni ezt a problémát: ifjúsági programjaikkal csak az eleve érdeklődőket szólítja meg és mutatja fel, színész diplomát szerezni a hatalmas túljelentkezés miatt ma is ugyanolyan nehéz, mint tíz vagy húsz évvel ezelőtt.

Magyarországon jelenleg két felsőoktatási intézményben szerezhet színész diplomát az erre vágyó. Budapesten és Kaposváron. A fővárosi egyetem nagy múltú és presztízsű, kiterjedt kapcsolati rendszerrel bíró, a vidéki egyetem új, alig több mint tíz éve működő, tradíciókkal, hagyományokkal, stratégiával kevésbé vagy egyáltalán nem rendelkező intézmény, melyet elsősorban az új színészképzés lehetősége, ebből kifolyólag a budapesti iskolával történő szembenállás hívott életre. Mi ez utóbbiban diplomáztunk 2009-ben.

Az új és a régi azonban a gyakorlatban kevéssé érzékelhető. A hazai színészképzés jórészt ugyanarra a színházi munkára készít fel, melyet a színészek hatvan, hetven vagy akár száz évvel ezelőtt (is) végeztek. Egyszerűen szólva megtanítják, hogy abban a pozícióban, amit a színész a megkövesedett színházi hierarchiában elfoglal, mit kell csinálnia, hogyan kell működnie, milyen elvárásoknak kell megfelelnie ahhoz, hogy sikeres legyen vagy lehessen. Alapvető probléma, hogy a színészre nem gondolkozó lényként tekintenek, hanem olyan végrehajtóként, aki mindig és mindenkor a hierarchiában felette álló rendező akaratának veti alá magát, és nem kérdez.

Színházi körökben elterjedt anekdota, hogy a felvételin a bizottság azt a feladatot adja a jelentkezőknek, hogy akárhogy is, de kerüljenek a teremben lógó csillár tetejére. Aki megkérdezi, hogy miért, abból lesz dramaturg, aki elkezdi tervezni, kitalálni a lehetséges megoldásokat, abból lesz a rendező, aki pedig egyből megcsinálja, na, abból lesz a színész. És mindez nagyon igaz.

A rendszer azonban nagyon megváltozott. Ma már nem mindenkinek elég, hogy megelégszik azzal, ami a diplomájában szerepel. A generációm gondolkodása merőben eltér „mestereim” gondolkodásától. Úgy látom, hogy sokkal távolságtartóbbak lettünk, képesek vagyunk egy kicsit távolabbról szemlélni a közegünket és a saját művészetünket is. Másképp vagyunk fanatikusok, már nem hisszük el, vagy legalábbis nem vagyunk biztosak abban, hogy a munkánk nélkülözhetetlen. Eleve nem látjuk úgy, hogy a színház nélkülözhetetlen lenne. Piac van, az általunk létrehozott előadások termékek, melyet el kell adnunk.

Változás állt be abban is, hogy a frissen kikerülő alkotók, akik így fogalmazzák meg magukat, az esetek többségében nem számíthatnak állami támogatásra. A szabályozás értelmében három évig nem pályázhatnak működésre, így projekt alapon kell gondolkozni, sosem lehet látni a következő lépés utánit. Ez az állapot nehezíti meg a legjobban a szakmai létezést, mert teljes mértékig tervezhetetlen és végtelenül kiszolgáltatott.

Egyedüli megoldás az egyéni út és stílus megtalálása. Mindebben a Trafó Kortárs Művészetek Háza hatalmas segítséget nyújtott, ahol 2013-tól kezdve minden évben létrehozhatunk egy produkciót. Itt játszuk Család trilógiánkat, mely Ibsen és Strindberg műveit dolgozza fel, a Tágra zárt szemek próbája és a Csehov, mely a szerző szinte összes művéből állt össze.

Mi már diplománk megszerzése előtt, párhuzamosan a tanulmányainkkal elkezdtünk lakásszínházi előadásokat létrehozni Budapesten. Ezek az előadások egyszobás lakásokban voltak megtekinthetőek. A teltház három színész és maximum hat néző volt. Egy asztalt ültünk körül, így zajlottak az események. Innen nőtte ki magát első nagyobb figyelmet kivívó előadásunk az Ibsent a nappalimba! (Hedda Gabler), mely megrendelhető, azaz mi megyünk el a nézőkhöz, akik meghívnak minket a saját otthonukba. Az előadás háromszereplős, bárhol előadható. A felvetés az, hogy mi lakunk ott és a nézők a vendégek. Ebben a munkákban kezdtük el keresni a fikció és a valóság keverésének lehetőségeit és ezzel a munkánkkal, köszönhetően annak is, hogy igen népszerű és már közel 200 lakásban adhattuk elő, kísérleteztük ki azt a ránk jellemző stílust, színészi milyenséget és minőséget, mely minden előadásunknak a sajátja lett.

Érdeklődésünk középpontjában mindig a színész és annak személyisége áll. Nem hiszünk az átváltozásban, a kaméleonként átalakuló színészben. Minden próbafolyamatunkban a színész és a szerep közös halmazát keressük. Rendezőként csak az érdekel, hogy a színész milyen megoldást hoz a felmerülő helyzetekben.

Munkáinkban mindig nagy klasszikusokat, Ibsen, Strindberg, Flaubert műveit használjuk. Próbafolyamataink a megszokottól eltérően négy hét elemzéssel és asztali próbával kezdődnek. A színészekkel itt addig rágjuk, elemezzük a szöveget, amíg azt már teljesen magukénak érzik. És már itt bekapcsolódnak az alkotói folyamatba azzal, hogy átfogalmazhatják, átírhatják a szöveget. Az olvasópróbára viszek egy erősen átírt és meghúzott szövegkönyvet, de ez inkább kiindulópont, a koncepció vázolása.

Az asztaltól csak akkor állunk fel a térbe, amikor annak már van értelme, a színészek tudják a szöveget és tudnak a mozgásra figyelni, de még inkább a jelenlétre. Rendezőként sosem izgat, hogy mi hol hangzik el – azért sem, mert a nézők mindig körben ülnek, sokkal inkább foglalkoztat azonban, hogy a színész őszinte legyen és teljes mértékig képviselni tudja az adott karaktert. Ha jól sikerül a próbafolyamat, akkor a végére a színész nem tud hibázni, nem fordulhat elő olyan, hogy elfelejti a szöveget, mert nem is a szöveget mondja, hanem a gondolatot. Éppen ezért az előadásinkban a színésznek megvan az a lehetősége, hogy eltérjen a leírtaktól, kihagyjon valamit, vagy jobban kibontson egy helyzetet, ha azt érzi, hogy erre szükség van. A bizalomnak ez a foka csak nehéz munkával elérhető, de megéri a fáradozást.

Nagyon kíváncsi vagyok, hogy a generációm, a mai huszasok, fiatal harmincasok, meg tudja-e újítani a színházat vagy minden friss kezdeményezés csak egzoitukus kísérlet marad és végül beleolvadunk a meglévő rendszerbe. Én optimista vagyok.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here