First: positionality. I am a man (though a distinctly genderqueer one), I am gay, and I am white. I am cognizant of the hypocrisy that comes with being a white gay man taking up space to talk about white gay men taking up too much space. However, I believe it to be wholly irresponsible to place the burden of dismantling oppression solely upon those it most affects, and I hope white queer communities, especially my fellow white cis gay men, will be able to better internalize it better coming from an insider.

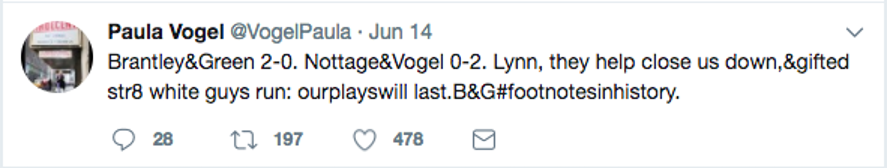

Theatrical practice has a long and storied history with queerness worldwide, that much is evident. Many on the fringes of society have found an affirming home in theatre, and many of us have come to find community and family through theatre throughout our lives. Theatre has not, however, been completely free of the pervasive hegemonies that seep into every facet of society. Hegemony refers to the (often) invisible systems of domination or control that one social group with more power exerts over other groups with less power. The ongoing pressure of settler colonialism creates a multitude of hegemonies in American culture that wiggle their fingers into everything from the most minute of zoning codes to the massive systems of inequity that allow the climate crisis to continue. If left unchecked, unhealthy systems will develop hegemonic elements, upholding patterns that privilege the same individuals repeatedly. As the conversation about effective inclusive practice in mainstream theatre in the United States becomes more complex and intersectional, the group that is most often able to utilize positions of power unchecked is white gay theatremakers and administrators.

It’s essential to acknowledge and accept how a person’s individual combination of identities can levy or revoke privilege within a system. To account for this complexity, sociologists use the term “one up, one down” identity—a group of identities within an individual that hold social capital through some traits and lose it through another. The idea is that an oppressed identity (i.e. a person’s queerness) offers safety from the power and responsibility inherent in a concurrent dominant identity (i.e. a person’s identity as white, cisgender, male, able-bodied, etc.) when both are present in the same individual. In American theatre, the idea that every marginalized identity translates into an equal share of the oppression faced by every other is irresponsible and reductive of the large-scale structural inequities that limit the voices of thousands of brilliant artists. It allows the notion that pieces of theatre by, about, for, directed by, designed by, and/or produced by cis white gay men are enough queer representation to fill a company’s season to persist and dominate. Recognizing and rejecting this assumption is a vital part of intersectional feminist and anti-racist practice.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here