These plays offer powerful—even radical—alternatives to the prevailing gender system, thrilling audiences to this day. Playfully engaging the male dramatists of their time, they imagine gender-bending protagonists who stand out for their wit, resourcefulness, and agency. The voices of these seventeenth-century playwrights add an important dimension to the JUBILEE, reminding us that women writers have long offered an alternative point of view, not only producing their own classics but helping to shape and transform the traditions in which they work. In the context of JUBILEE, their works can remind modern audiences that the past was not always conservative simply because it was past. Instead, their plays show abundant evidence of more challenging, less traditional points of view, as long as we are willing to stage them.

Among Spain’s most celebrated playwrights of the era was Ana Caro (ca.1601–ca.1645). A recently found baptismal document suggests that she was born into slavery in Granada and subsequently adopted by an officer there. This makes Caro all the more intriguing, as a female dramatist—possibly of African origin, possibly a descendant of Spain’s forcibly converted Muslims—who brings to the fore in her writing issues of social justice.

Caro made her living as a playwright in Seville and Madrid. She has her own male characters note how remarkable this is—a woman writing!—with a mix of surprise and sarcasm. Caro was widely admired by her contemporaries, both male and female, and her powerful vision of female agency continues to impress audiences today. She had a remarkable facility as a playwright, and her daring critique of gender norms shines in Valor, agravio, y mujer (The Courage to Right a Woman’s Wrongs), probably written in the 1630s. The play reworks the Don Juan myth, popularized by the wildly successful The Trickster of Seville. As most audiences know, Don Juan is an unfaithful narcissist who seduces women only to abandon them once he gets what he wants. True to form, Valor’s Don Juan abandons Leonor, our heroine, once he has slept with her. Leonor becomes “Leonardo” and follows her fickle lover to Brussels, where s/he runs circles around him and seduces the noblewoman that Don Juan courts next. Leonor/Leonardo is witty, strong, and sympathetic, while the role as written gives actors a chance to explore an extraordinary gender position.

Beyond the English-language tradition lies a rich corpus of classical work that was, and remains, remarkably hospitable to women.

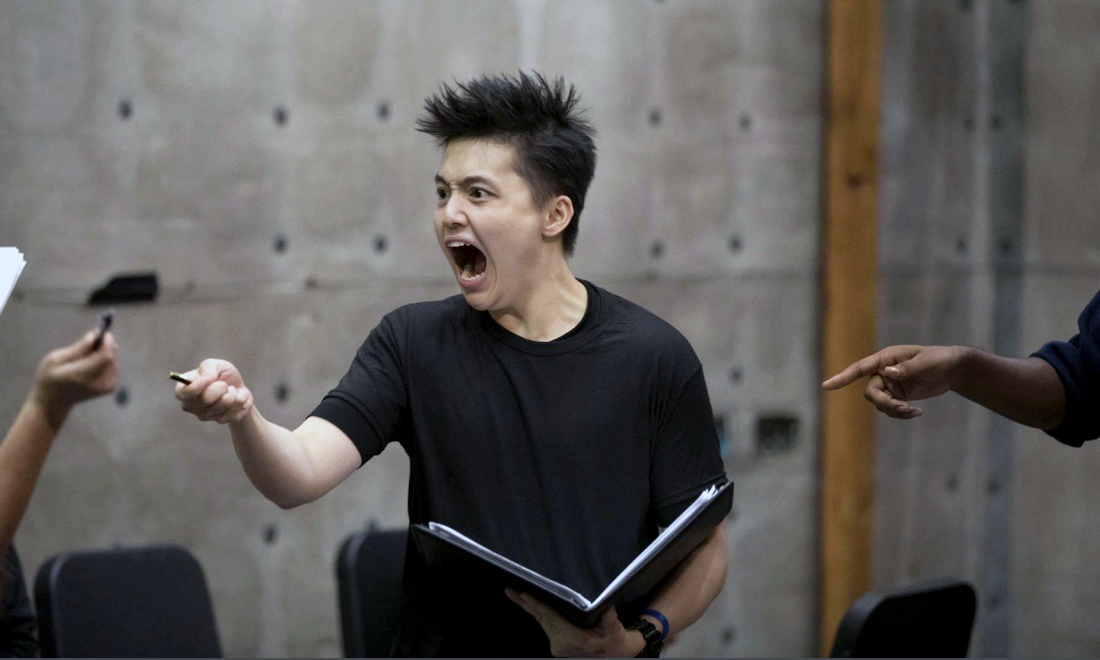

Caro’s play provides modern audiences with the kind of transformative, inclusive revision that JUBILEE programming is designed to encourage. In the last two decades, Caro’s Valor has generated significant interest on stages around the United States and Spain. In New York, Leyma López directed Valor for Repertorio Español as part of the 2017–18 season, underscoring the continuing relevance of the play to our current moment: “It’s a strong statement when a woman is the protagonist of the whole story and forces us to listen to her as a human being,” López explained in an interview in Comedia Performance. UCLA’s Diversifying the Classics project, which we are part of, has now translated Valor into English under the title The Courage to Right a Woman’s Wrongs. First presented in a staged reading at UCLA in November 2019, directed by Michael Hackett, Courage will have a full production there in winter 2021 and will be presented as a staged reading as part of Red Bull’s Revelation Readings series.

A generation after Ana Caro’s death, one of the most famous playwrights and poets of the Spanish-speaking world was Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (ca.1651–1695), who wrote in New Spain (colonial Mexico). Though best known for defending women’s rights to think, learn, and write in her wry treatise, Response to Sor Filotea, as well as for her feminist poetry, Sor Juana also wrote comedies, farces, and autos sacramentales—religious plays that marked Catholic holidays. Her work crossed the Atlantic and was celebrated in Europe as in the Americas, yet she introduces in her writing a number of distinctively American details, placing her homeland of New Spain on the literary map.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks!

Hi Kevin! It's available here along with our other translations of this amazing corpus: http://diversifyingtheclassics.humanities.ucla.edu/initiatives/translations/

Where can we find copies of these scripts?!?