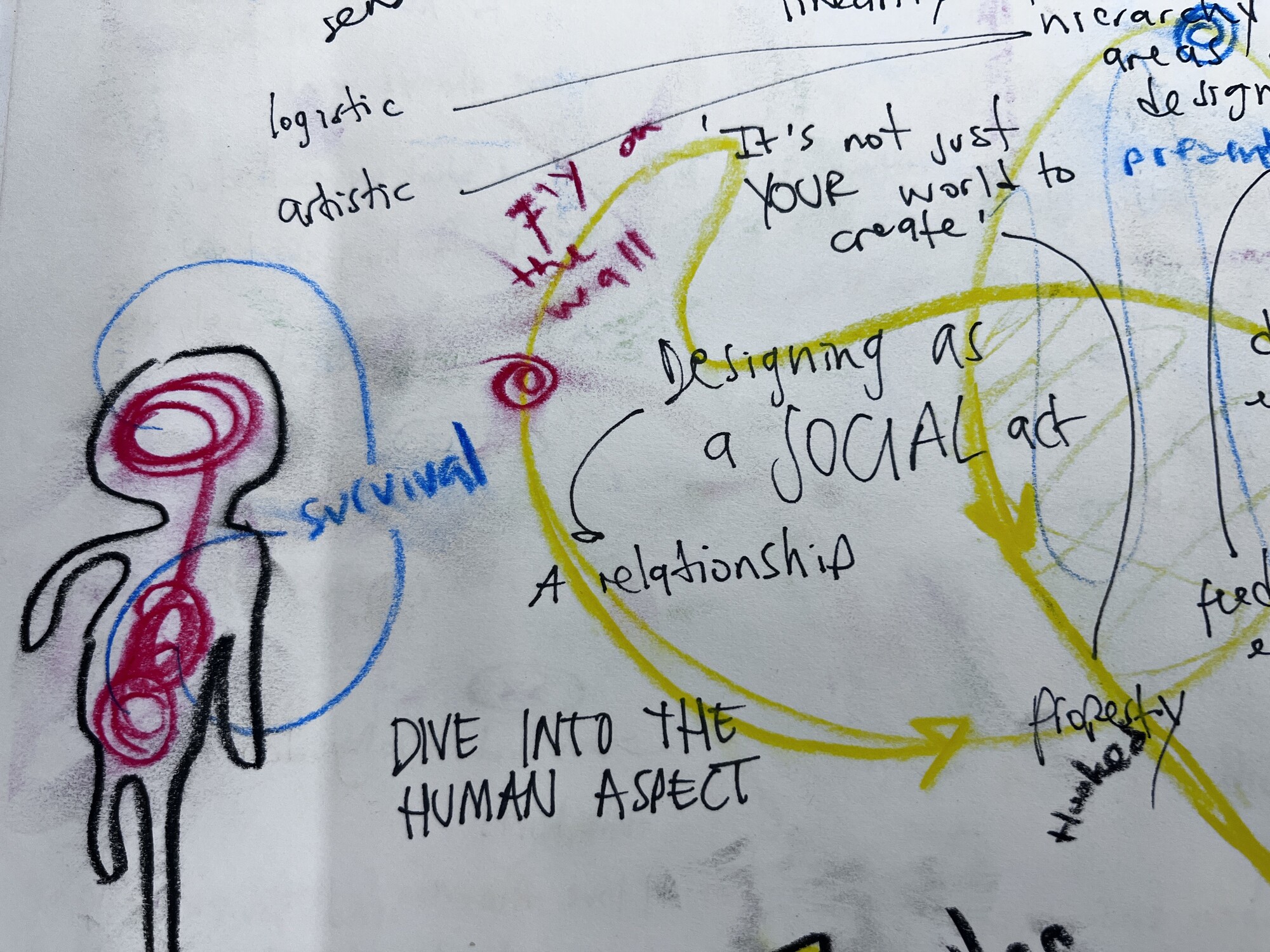

After lunch, which included a discussion with the full Colaboratorio cohort about the complexities of Latinidad, Luzet surprises us by saying he needs to tap out and leave for the afternoon. The lunch wasn’t a break for him because the topics covered in the large discussion drained him. Faced with this challenge, the words from Eme’s poem confront us. What are the boundaries? How much do I want to be in this story? In this vulnerable moment, how do we hold our fellow human?

We do it by remembering to play.

Alejandro, who has been functioning as the group facilitator, proposes socialization outside, because you never know where inspiration comes from. Luzet agrees. It’s his first time in Portland and he wants to explore. He saw a curio shop nearby called the Odditorium and had been wanting to check it out.

As we discuss this possible shift in activity, Benito shares he is fine going elsewhere, but he’s trying to figure out where we are going—not literally, but in the process. He admits he’s feeling lost. Eme responds: we often feel a pressure to move forward, but what is forward?

So as a group, we embark on the field trip—the first of many we will enjoy throughout the weekend. In fact, one such field trip will give Benito that moment of clarity he was looking for—and open our floodgates for creation.

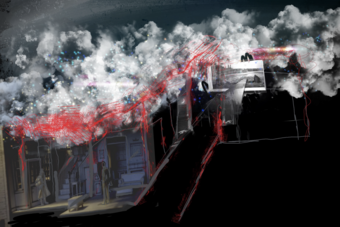

“There is something beyond that house coming in, a force of nature that our characters don’t understand, but it’s breaking away those barriers in a physical special sense and in a narrative sense. There’s an acknowledgement of the world outside, then our characters as the story progresses get to share this space. They all have to go through a journey to open themselves.”

—Alejandro Melendez, discussing the play

At the Odditorium, synchronicity gives me a wink. The store’s full name is the Skeleton Key Odditorium—an apt name for a place where we’ll access new knowledge. Away from the intense political discussions of our LTC lunch, as well as the intellectual and creative interrogations of our work room, new sights and sounds bring stimulation to the unconscious and give us a chance to learn more about one another. They also give Luzet, who loves Dia de los Muertos, an opportunity to visit the store’s Museum of Death. Interestingly, the topic of grief, which we identified as the core of the play, ends up becoming a presence on our trip.

We return to our classroom, and Pedro leads a discussion on the choices we have for a theatre stage. Fresh from the outside, with the memory of our outside flow, we are able to intuit the flow of energy in various seating configurations. Strong winds once wild in the play now take direction, and we identify one configuration in which elemental forces pull us together. We break boundaries, flipping the stage so that character Juana enters from an unusual direction. The audience will now be looking up into the “sky” of the raked staged instead of having it behind them. With this shift in perspective, we’re poised to see Alex’s bedroom in a new light as he ascends to be held in angel arms.

The reason we were able to get to this epiphany is that we were in a position to shake up our own processes.

Night turns into day three, and at Luzet’s urging, the group uses morning team time for another excursion. They head to the Portland Art Museum for the "Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio” exhibition. Now it will be my turn to tap out and sleep in, as the fatigue of my flight misadventures is catching up with me. I meet the group afterward at the farmer’s market. We tour the tents with their samplings of fruit, flowers, food, and sweets—a complete contrast to the decay of the curio shop a day before. But from death comes life, and today is the day that our creative process will evolve into hyper-vitality, thanks to our director, Benito, having an epiphany pushed by the invisible hand of the wind.

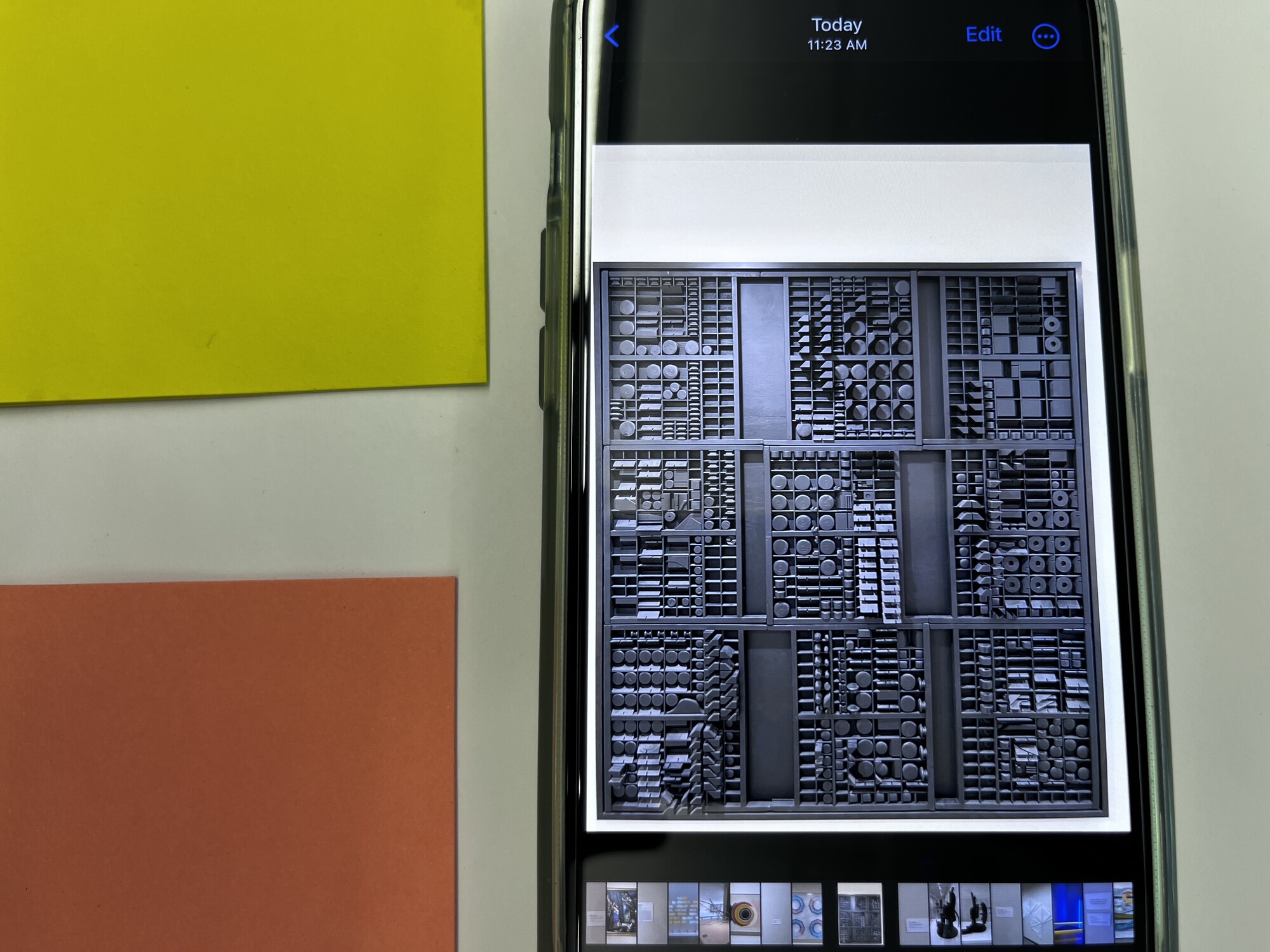

Benito tells us the story: while at the museum, he became separated from the group. He walked into another gallery, was looking at a sculpture, and overheard two people discussing the same piece. The woman explained that the artist was known for finding found objects and painting them black in order to “disguise their true nature."

When she spoke those words, Benito had a eureka moment. The characters in the play were also disguising their true nature! Each character was hiding something except for the father, which is why he stood out to us as different. The play’s transformation occurs when the characters unveil their disguises to become their true selves.

“The reason we were able to get to this epiphany is that we were in a position to shake up our own processes,” Alejandro observed. “There is a sense of serendipity and coincidence, that perfect alignment of situations that put us to where now we have a sense of clarity and direction moving forward.”

Back at our classroom workshop, the creative floodgates open. Within two hours, we develop the framework of the “That Night” scene. Luzet, having previously focused his design concepts mostly around costume colors, starts experimenting with textures—perhaps a result of our newfound understanding of character psychology. In response, Alejandro tests different lighting filters over the fabric swatches, thinking about the moonlight as well as the family’s story arc. Pedro demonstrates a complementary fabric stretched over open structures to indicate the boundaries of Alex’s bedroom.

I ask to see a picture of the sculpture that started it all. I’m curious about the artist and swipe to see the museum label. The artist is Louise Nevelson. But what really gets my attention is the title of the 1973 piece: End of Day Nightscape ll. I smile, wondering who is crafting our Pinocchio strings.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you to my teammate Pedro L. Guevara for providing audio recordings of day one.