Toronto, often deemed “the most multicultural city in the world,” is the largest city in Canada. There’s a thriving theatre scene here, with almost everything you could ask for, and the artists whose work we’re treated to are some of the best in the country. In this city series, you’ll hear from several of these theatremakers about the Toronto theatre landscape through their eyes. In this conversation, award-winning actors Maev Beaty and Bahia Watson discuss what it’s like being women in the industry today. —May Antaki, series curator

It’s Important to Have Your Community

Maev Beaty: We’re sitting here in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto.

Bahia Watson: It’s my first time here. It’s really beautiful, and there are blue skies.

Maev: There are snacks...

Bahia: With us, there are always snacks.

Maev: We met acting at Nightwood Theatre—Toronto’s feminist theatre company—in their production of Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad in 2012, which was a show with a whole bunch of women in an ensemble.

Bahia: A woman director, all the designers were women...

Maev: And then we reconnected doing The Last Wife, written by Kate Hennig, at the Stratford Festival in 2015, before remounting it in Toronto at Soulpepper in 2017.

Bahia: For which you won the Dora Award for Outstanding Female Actor! Those are like the Tony Awards of Toronto, for those who are unaware.

Maev: You, you’re a theatremaker, storyteller, film and television actress, animation voice artist, and co-creator of MASHUP, a feminist circus variety show.

Bahia: And you are a powerhouse storyteller extraordinaire, who has worked on... How many new plays?

Maev: Twenty-four world premieres, and counting.

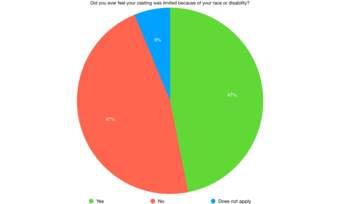

Bahia: We’re here to talk about being women in theatre in Toronto, and, I have to say, before we dive in, that I always find these kinds of themes difficult to zero in on because I can’t really talk about being a woman without talking about being a black woman. I’m black and that’s a part of it.

Maev: And I’m not a woman of color. Also, we are both cis-gendered.

Photos courtesy of Bahia and Maev

Bahia: I was talking to a director recently and he was like “since #MeToo” and I find that language really interesting. It’s like, an era, an epoch.

Maev: Have you noticed anything different about the way rehearsal rooms are run in Toronto since the #MeToo epoch?

Bahia: The union here, Equity, has had to become more vocal and deliberate about their guidelines and protocols around sexual harassment. There are definitely more pamphlets. On the first day of rehearsals, stage managers are now required, I think, to talk about acceptable and unacceptable behavior and how to report issues in a safe way and all that.

Soulpepper’s HR department makes a speech at the start of rehearsals about their commitments to making the workplace safe, and how they’re there to listen. There is definitely a new energy of accountability in the room, which is good. Sometimes I think people are just afraid of getting in trouble with feminists and the internet and so they’re trying to cover their bases, but maybe that’s being cynical. I do think many people welcome the channels of discussion the movement has busted open.

There are also some new conversations around on-stage intimacy and intimacy choreography and consent, which I personally appreciate a lot. In some rooms though, not all. I think that’s one area that could still use improvement. Also, some companies are scrambling to hire more women, while some... aren’t. It’s all over the place. Conversation moves faster than structural change. Have you felt any big changes?

Maev: I worked on six female-directed projects in the last year, in and around Toronto, each deeply fulfilling, and recently I’ve been getting curious about whether there is a difference between those processes and the ones for projects lead by men, about why ultimately it felt like I was more of a collaborator with a female leader and generally more of an interpreter and executor with a male leader. What were the differences, was it the leader’s language? Vibe?

Then I started asking myself: Maybe it’s me? Maybe the environments are similar, but because I know one is being led by women and one is being led by men, perhaps I’m behaving differently. I do have a hunch the female leaders carried themselves differently to some degree, but I think I’m also giving myself more permission to not apologize or explain and just get on with the work, to take up more space in those rooms simply because they were led by women. I feel more permission to make offers and take risks while assuming we all know that’s not my final performance. In rooms led by some men, there can be a feeling that when I do this, it’s going to be interpreted as making a mistake. As in, “Oh no, is she going to do it like that??”

Bahia: I know what you mean. It’s different when you feel like an equal, and when you don’t and thus feel like you have to articulate and assert your value, explain why you’re allowed to be there and contribute. In most of the theatre work I’ve done, unless I produce it myself, I am usually the only, or one of two—max—people of color in the room, and it definitely changes the way I express myself. The more I feel like an outsider, the quieter I am. It’s exhausting: the explaining, the trying to lift yourself up in someone’s perception.

I do have a hunch the female leaders carried themselves differently to some degree, but I think I’m also giving myself more permission to not apologize or explain and just get on with the work, to take up more space in those rooms simply because they were led by women.

Maev: We’re now in the light therapy room in the museum, and the first time I came here was because I was really dark the day before, and it was because of a theatre review.

At the time, I was acting in a show in Toronto, written by a man, a famous playwright, who had, to my understanding, an ‘othering’ relationship with women in his work. I really played with the idea of objectification and sexualization, the femme fatale and eroticism. I did it consciously, using it as a chance, as a primary creator, as an actor, to crack open the question of women in this playwright’s work with affection and curiosity, really making a series of choices around it.

Ironically, one of the reviews in a major newspaper written by a woman said a problem she had with the show was that my character was “oversexualized.” I think she might have used the word objectified. She also mentioned that I spent part of the show with my “backside to the audience.”

In theory, I think she thought she was advocating for me, but what she didn’t take into consideration was that I’m not just a pawn of the director. She took my agency entirely out of it as if I, Maev Beaty, at this point of my career, was just obediently walking around in my bathing suit, doing whatever the men were telling me to do. I ended up feeling incredibly objectified and shamed by her, which I think was certainly not her intention.

The review really made me spiral down and made it hard for me to do the show for many days in a row, which was this sort of funny backlash of good intention, a stringent feminist view of work these days.

I think a really big thing now—in Toronto and also elsewhere—is sexual empowerment but also, as you mentioned, creating safe environments and being sensitive to triggers. It’s really complicated and we just have to work through it.

Bahia: I wonder if there’s a way to constructively engage in a discussion with that reviewer. Because older material is especially hard, for modern women, modern people, really. On stage as well as in the audience. The times they were written in were more oppressive and so there is a lot of work being done trying to find how else we can shape the words, how we can bend the story to do something else for us.

Plays at best are springboards for important discussions, and I think that would be an interesting one. What does empowered expression look like? And what does empowered expression feel like, on the inside, as an actor?

Maev: Part of the culture shift we’re in right now, I hope, will include an understanding that everything you see in art is a choice ultimately agreed to by all the artists involved. This is part of dismantling patriarchy: to both insist and then assume all artists involved had a voice. This is the work right now. And I hope our culture can continue to make, as my husband Alan Dilworth says “risky work in safe spaces, not safe work in risky spaces.

Maev, Bahia, and Sara Farb in The Last Wife. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Bahia: I definitely learned about this a lot when I worked with an intimacy choreographer. Safe boundaries actually make me feel freer to take bigger emotional risks.

Maev: I believe when done well and carried through by the actors, intimacy work can empower the actor to stay in the scene instead of thinking: “Will he or won’t he go further, will I have to protect myself because we don’t know the boundaries?” It ideally helps you to think: “Ah, King of France, I wish to rule alongside you and your awesome mouth,” or whatever.

Bahia: Exactly! This is one area I think I could be vocal, especially in keeping the lines of communication open with directors and stage management in how these scenes are evolving throughout the run.

Maev: I think how we are making work is changing. It does a disservice to everybody to think the director has all the answers. Actors are primary creators, not just interpreters. So it also has not made sense to me when there’s a system set up where actors are simply waiting to receive instructions, then carry them out, and then find out how they failed in carrying them out.

Bahia: There have been times when I’ve felt like a pawn in someone else’s idea, where they’re like, “This is what you think, this is what you do.” I hated that. I need to have room to make choices, ask questions, and participate in the answering of the big questions like, “Why are we even telling this story? What is this story actually doing in the world?” Without that space to participate, it can be really depressing.

Maev: You became such an important person in my life during that Stratford year when we did The Last Wife. We created this friendship, but also a true commitment to the small circle of actresses we met with every two weeks for the entire season.

Bahia: I loved our gatherings.

Maev: The Stratford Festival is so big and has such a big job to do—the processes can be overwhelming. But it’s vital for women to continue to take risks and be brave in our work. Our group of women committed to supporting each through that no matter what.

Bahia: It was so important, especially at a time when theatre in our community was undergoing changes, because of #MeToo, and trying to break down problematic patterns of the past. It can be really intimidating, asserting yourself, and maybe you’re not the most experienced person in the room, or you’re the youngest, or the only woman, or the only person of color, and so it was useful to be able to check in with each other, to be reminded that we’re not crazy, we’re not imagining problems where they don’t really exist, or making up oppression where it’s not. It’s not easy telling a colleague that their jokes are actually offensive, or articulating aloud that they’ve made some changes to the intimacy staging that you haven’t discussed and are making you uncomfortable.

In this live art form that requires such trust, you end up worrying that if you say it wrong, someone will shut down or close up on you. Having a group of women come together to brainstorm ideas and constructive ways to address situations, to carry ourselves forward in our work, helped.

In this live art form that requires such trust, you end up worrying that if you say it wrong, someone will shut down or close up on you. Having a group of women come together to brainstorm ideas and constructive ways to address situations, to carry ourselves forward in our work, helped.

Maev: Our city and industry were already churning from Weinstein, #TimesUp, and #MeToo and then when the allegations against Albert Schultz at Soulpepper came forward, everyone—not just our small group of women—urgently gathered to support each other, even coming together in organized groups like Got Your Back.

Bahia: That drastically shifted everything. It was huge.

Maev: And at the same time it’s hard to say, “Wow, in the last year and a half we’ve really been wrestling with the patriarchy.” HA! We’ve actually been wrestling with the patriarchy all along. But it feels like there’s been a lot of energy recently put into figuring out how to move forward in our city’s art spaces.

Bahia: Something has cracked open. Powerful people who seemed invincible were being publicly held accountable for their actions, and a lot of women and feminists saw the crack in the ceiling and were like: “I gotta seize this moment, I gotta get in, I gotta make sure to not let it close.” I definitely feel that way. I want to not just lean into the change, but like shove myself right in there and seize that seat at the table. But the excitement of progressive conversation is one thing, and the reality...? Change is slow.

Maev and Bahia in The Last Wife. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Maev: I was talking with someone the other day about our work as performers and the demand it has on our prefrontal cortex. How we are literally in a part of our brain that demands such presence and rigorous attention in order to be present, to feel the audience, to feel each other, to create in the moment, to be supple and responsive. You just can’t stay in that part of your brain forever, you have to take breaks.

But this window of opportunity you’re talking about—“We can’t let it close, we have to be there”—asks us to stay in that place all the time, both in the work and in the rehearsal hall or theatre. Every day of work now I feel, I must be alert, I must be checking in and connecting with the most vulnerable people. Noticing the quiet people instead of the most powerful and loud. Being a witness, not a bystander.

Gathering with others to unload and share that stuff and ask for advice is so invigorating.

Bahia: And replenishing—an important part of self-care in progressive times, as we try to activate and sustain movements of change. That gathering, where you feel understood, where you don’t have to explain, where you can be yourself. Unload and discuss. Break things down and build each other up. Have tasty snacks! It’s so important because the work of change, the work of evolution, revolution, is exhausting and depleting. It’s important to have your community.

Maev: There is a strong desire for a Toronto theatre culture change, both in what our work is about and who is making that work. This city has the potential to globally lead the way in terms of intersectional representation on our stages—literally the entire world is represented in our citizenship—but we have been so slow to do that.

We have had this incredible slew of work over the last year and a half—which is ongoing—that have been female-led. A lot of big casts filled with women, like School Girls, The Wolves, Girls Like That, Now You See Her, Guarded Girls.

Bahia: Yeah, let’s be positive for a second! One theatre practice I’ve experienced here in Toronto that I haven’t experienced elsewhere are land acknowledgments, where the presenting company, before the show begins, will acknowledge and name the First Nations on whose land the show is being performed. I was talking to an American actor friend about it, how I can name the nations—in Toronto it’s the Mississaugas of the New Credit, the Anishnawbe, the Haudenosaunee, the Wendat, and the Huron Indigenous Peoples—and how audiences are being taught that Toronto’s original name is actually Tkaronto.

A lot of the general public doesn’t know that, and while there is certainly a lot more inclusive work to be done, I appreciate that it is, at the very least, paying respect where it is due and not repeating a history of erasure. Little steps forward...

Maev: They’re little but they’re changing the center of things. What I appreciate about what I perceive as a feminist, collaborative leadership model that’s starting to gain credence in our theatre culture is that there’s a real faith in process. By the end of next year, most of our city’s theatres will have undergone a leadership change. My hope is that these new leaders are comfortable in a state of not-knowing, of humility. None of our old interpersonal clothes fit anymore. We’re all naked.

Even with the land acknowledgements, we’re trying out a bunch of different ones. There’s been a lot of response from the Indigenous community about whether they feel it is a worthwhile practice and how it should be done. It’s important to not bring shame into the process of change because we’re going to make so many mistakes.

What we started talking about—being willing to take risks—let’s just assume that we women know what we’re trying to do, and assume that we’re making choices so that we can make mistakes and then fix them and be in dialogue about it. Because, as you said, change takes time. The old way doesn’t work anymore, but there’s no point of arrival.

I want to not just lean into the change, but like shove myself right in there and seize that seat at the table. But the excitement of progressive conversation is one thing, and the reality...? Change is slow.

Bahia: It’s step by step, trying things out. Working towards equality, have difficult conversations. Challenging each other, pushing each other, and not diminishing each other. I’m going to digress here...

Maev: Do it.

Bahia: In terms of the inclusion, diversity conversations—

Maev: I don’t think it’s really a digression, it’s right in the middle of it actually. Said the white woman interrupting.

Bahia: Recently some colleagues invited me to a rehearsal for their show and, as it turned out, they wanted to know if I thought they were being racist, or if it was appropriation. I didn’t feel they were in their production but I left feeling tokenized. I want to help my friend but at this point—and especially leaders with experience and power—do better! I mean, if you want to know about racism, read a book. If you want to know about appropriation, listen to a lecture.

There are so, so many resources available to understand the nature of discrimination and oppression, and it’s unfair to belabor a marginalized person with the task of informing you on these things. And this happens a lot. If you have power, do the work yourself, or hire a consultant and pay someone to do the work. You can literally take an anti-oppression workshop for artists in Toronto—I’ve taken it. I can’t be your token diversity and your sensitivity reader, which is what they call it in publishing.

Maev and Bahia in The Last Wife. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Maev: An incredibly successful Canadian female playwright we both know was asked by a male colleague to read something and he actually said to her, “By the way, don’t feel like you can only comment on the female characters. I want to know if the male characters...” It was sort of the same thing, not the same thing, but similar.

Bahia: Yeah, tokenizing our intelligence. It can be frustrating. But, at the same time, I don’t want to only focus on the negatives and what’s not working. I just think there is so much to be gained in healthy, meaningful, thoughtful, and genuine inclusion—not forced diversity because you’re just trying not to get in trouble or and getting someone to help you check off boxes so you don’t get called out.

Maev: I remember reading, oh gosh I think it was Anne Bogart writing about the incredible moment of opportunity that happens after a crisis. That after something big—such as Weinstein or Schultz or Ghomeshi—there is a space that is created, a space of potential and change and unknown future that could be so much better than before, and that far too often that space gets shrunk by fear, fast. My hope is that this era of unknown does not move us to tick boxes out of fear, but helps us fearlessly stay big and stay open to something we aren’t used to or recognize.

Bahia: There is abundance in inclusion. The more people you include, the more room there is. Theatre is always referred to as a dying industry, like it’s always about to fade away. I think the more inclusive it is, the more people can relate to it, the more people will feel theatre is something important they want in their lives. Then we have more people saying, “This is something I want to be funded, this is something to see, this is something I want to support.” I’ve seen it happen. In shows I’ve produced, we’ve built it and they’ve come. People always comment: “I love your audience.” It make me so proud to perform because our audience looks like this city.

Maev: And this city is so incredibly bountiful. This city has everything, everything, everything you could ever want a piece of in terms of the global access.

Bahia: There’s so much potential for this city in particular, already having a huge, strong theatre scene, and having a slice of the world. There are literally people from everywhere here. On the subway, people speak every language, you hear it all the time. To be able to have that reflected in a storytelling scene is so exciting and would be a draw for other people to come here and experience the world in one place. I think the potential for inclusion is abundant and the more people invest in it, we will see the returns.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here