Our Water is Melted Snow ostensibly looked like a pandemic-era Zoom meeting—on my laptop I witnessed Knight and other audience members arranged in a grid. But the hour-long performance felt like live experimental performance. Knight built forms of intimacy and liveness—despite mediation—by breaking online standards, like changing our Zoom names based on conversations during the performance. At one point she asked me about my living room setting and I mentioned my couch came from Craigslist; soon after my name was changed from “Jasmine Mahmoud” to “Craigslist.”

Knight fashioned non-narrative attention by bringing herself and objects close the screen: a paper that read “This is the Quarantine Report,” her face looking through a small hole, a yellow backdrop, and a Black female figurine that she slowly turned in a makeshift cone. She built spontaneity by weaving improvisatory conversations with the audience with loosely scripted remarks. And despite performing from New York City, Knight built Our Water with, as Wa Na Wari’s Elisheba Johnson describes, “a Seattle-based site specificity,” from the show’s title to Knight’s recurrent questions to the audience about the city’s culture.

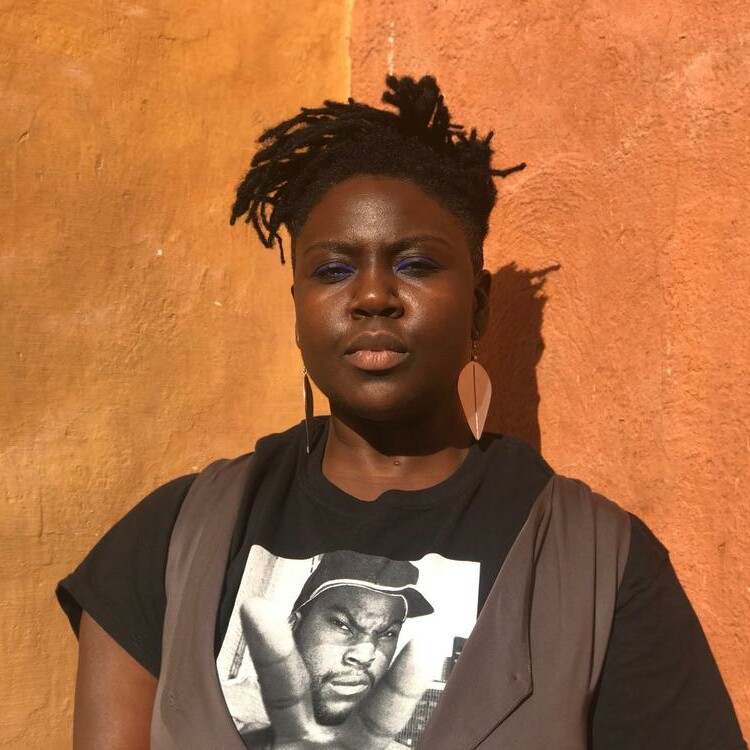

I reached out to Knight via video conferencing to discuss all this and the themes of vulnerability, Blackness, and connection. I was curious about geography and audiences, as well as her thoughts on staging and presence across screens.

Jasmine Mahmoud: How do you think about your practice in this current era? And how do you think about audience as part of it?

Autumn Knight: Due to the pandemic, I had to really rethink how I engage with audiences, what the essence of that is, and how that works with the delay of digital media or the digital/virtual apparatus. There’s so much connectivity that happens in real time—eye contact, physical contact.

This moment made me really think about how I communicate with an audience, and in some senses how I present work that is more in front of an audience and not engage with them as much as I normally would.

Performing online, I consciously think about the eye and the ear, really paying extra attention to these senses and thinking about what does and doesn’t work for the digital space.

Jasmine: How do you narrativize your practice? What issues, themes, and methods does your practice engage?

Autumn: In the general sense, my practice really thinks about the here and now. How can one tease out what is happening in this moment that might be submerged, that might be latent? Manifesting latent material is a thing I think about often—behavior and how changes in behavior can impact a room of people. Generally in my performance work, I end up talking about and experimenting with the idea of “authority.”

Jasmine: I teach at Seattle University, and before the pandemic I was used to meeting on Zoom, but then, with the pandemic, there was a quick move to teaching on Zoom. That transition was a lot. I know you make video and installation work. I’m curious about how your practice pre-COVID influenced the work I saw in May, and the work you’re thinking about now.

Autumn: Melted Snow made me think about what aspects of my work I want to continue to do, but also what needs to adapt. How can I experiment with other things I’m interested in, other visual languages, other materials? It made me think about scale and how the Zoom lens is like an eye. It made me think about what you can see through this little eye. I work with intimacy a lot. How do you create intimacy through this small portal?

I’m thinking through how to connect people who are all in their own homes. In a live performance everybody’s in the room—you can get people to sit close, you can ask people to move their chairs, you could manipulate the sight lines. Your body can be in different places but people can follow you with their eyes.

Performing online, I consciously think about the eye and the ear, really paying extra attention to these senses and thinking about what does and doesn’t work for the digital space. I love playing music before, during, and after live performances and looking for specific songs that go with the performance. When you play them through the computer speakers, it doesn’t translate. So what does translate? The voice translates.

I’m thinking about these tiny little things that I’ve got to give up. How do I maintain people’s attention, even in this space?

Jasmine: You did that really well by changing our names, or I assume that you were the person changing our names.

Autumn: Mm-hmm.

Jasmine: Watching an online performance, there are so many ways of looking at the screen, and so many other places to look other than the screen. Right now I have my computer in front of me but I can see so many other things in this room. You changed our names during the performance to echo the conversations that were happening in the show. After one audience member extemporaneously brought up the idea of Jheri Curls, you began to ask others about this hair product and style. And then you changed our Zoom names—some audiences members became named iterations of “Jheri Curl,” “Jheri Curl 2.” It made me want to look at the screen at a time when we’re are all so sick at looking at screens.

To your point about the lens, I’m thinking about those moments where you held a figurine of a Black woman close to your screen, and slowly turned the doll. It was interesting to me the extent to which the doll, which I imagine was a few inches tall, became the size of the screen. It made me think a lot about figure and scale. It’s another way that you held my attention in that moment.

Autumn: While playing with the Zoom features beforehand, I realized that as “host” I could change everyone’s names. I thought I would choose a specific moment to change them, but then the perfect moment hit to do it. I wondered, Who would notice? How quickly would I need to do it so that people would notice other people’s names were changing too? What does it mean to someone for their name to change and for them to not have power over it?

I also wanted to play with some of the visual moments in the performance. I wanted to think through how to manipulate the screen and objects.

Jasmine: It wasn’t sinister, but for a moment I saw one of the people who I assume is white was named one of the Jheri Curls and I was like, “Oh, did that white woman change her name to ‘Jheri Curl’ too? What the fuck?” But I appreciated that “What the fuck?” In some ways, we think of these constants in the Zoom space or the virtual space, and we think of our names as constant.

What were some of your initial goals around Our Water is Melted Snow? How did you conceive of navigating Zoom and how did you think about your institutional and community partners, On the Boards and Wa Na Wari?

Autumn: I was approached by Elisheba Johnson at Wa Na Wari to work with them; I had met her the year before after a performance I did at On the Boards. I didn’t really have a particular idea. I am, in many ways, open to new material and then open to shaping it from there. So it began with a conversation with Liz about Seattle. “Okay, it’s going to be on Seattle time. It’s a Seattle organization, it’s West Coast. Maybe I should focus it there somehow to put it in some geographical place. So, what about Seattle?”

She said something about the Seattle Freeze. I thought that was such an interesting concept. We started talking about Seattle, and at the end of the first conversation she said, “In Seattle, our water is melted snow.” We also talked about Black culture in Seattle. I thought an inquiry about Seattle culture would be interesting, because it’s a Seattle organization and there would be more people from Seattle in the audience, so it would more than likely resonate with more people.

I also wanted to play with some of the visual moments in the performance. I wanted to think through how to manipulate the screen and objects. When I’m at the studio, I make things and play with things—I love playing with light. I also wanted to leave it a little bit open. I wrote some text, and I did read the text. Some of my other performance work is about opening up space for anything to happen—the things that are naturally there in the room, the things that are right underneath the surface—and providing opportunity to bust that open.

I have a hypothesis around Seattle, and the Seattle Freeze, and how it relates to white supremacy and xenophobia.

Jasmine: I would love to hear how you’re thinking about it.

Autumn: Inye Wokoma, a co-founder of Wa Na Wari, told me that he’s fifth generation Black Seattle and said, “I don’t understand the Freeze.” I thought this must be something that is generally felt but possibly particular to the white population of Seattle. I was also wondering if it was a cross-cultural phenomenon.

Jasmine: I’ve experienced the Seattle Freeze as a Black woman. Being frozen out and not feeling welcome. Here in Seattle, if you nod or say hello to someone, sometimes they will not look at you. Whereas in St. Louis, where I used to live, people would come up to you and say, “How are you doing today?”

I do think it is more with white people, but my Black friends who’ve moved here say they sometimes feel like zombies, because sometimes they’ll see a Black person and they’ll smile and give them the nod, and no recognition. I know people from here of different races and many of them don’t feel the Freeze, because they have their friend group.

I often teach about live performance as ephemeral. But that whole concept is differently framed now. How are you thinking about liveness and ephemerality, especially amidst physical distancing?

Autumn: I got a sense of that. My hypothesis is that the Seattle Freeze is subconsciously about resources and this beautiful landscape. The idea that, if we appear frozen and socially distant towards newcomers or outsiders, they won’t want to be here. We can have more of this to ourselves.

I’m from the South, and there’s so much of everything. People are friendly because there’s nothing to hoard. I’ve thought about America as a nation and the ways it freezes people out. Seattle presents itself as very nice, but is apparently unwelcoming to some. That was my general analysis of what I thought the Freeze might be.

Jasmine: I love that interpretation. I also think the Seattle Freeze produces a lack of vulnerability. I have not really seen much good realist theatre in Seattle, which I tie to how people can’t be vulnerable with each other here. A joke in the area with COVID-19 is that, when they first announced the stay at home order, many people were like, “Great. We’re good.”

One brilliant thing about your performance was how you were making us vulnerable in this odd space that we found ourselves in. Zoom is not vulnerable or invulnerable. It’s just odd and flattened.

Another question: The majority of the people on the Zoom call were in the Seattle area. So, even though ostensibly someone from wherever could have bought a ticket, it was a Seattle audience. Did you get a sense of where the audience members were coming from? Were you imagining them to be mostly Seattleites?

Autumn: I was imagining them to be a third from Seattle, maybe a few people from Portland, a third from New York, and a third from somewhere else.

Jasmine: Looking back, how does this work blend with the others you’ve been performing in the last few months?

Autumn: I did a performance the week after Our Water is Melted Snow. In this new piece, The Length, with Washington Project for the Arts, I used many of the same devices. I decided I wanted to include the lens, the light, text. I really created a new way to work within the space of that camera. I thought about how to frame myself, how much people need to see me, and how much I can give within the scope of the performance. For most of my performances, I am in dialogue with the audience as I travel around and move about a space. I am the performance.

Jasmine: In your show last fall, M _ _ _ ER, all audience members sat on stage in a haphazardly arranged round of folding chairs and you engaged us in sharing personal memories and, at one point, a carton of ice cream. Your body was central, and everyone’s head would follow you. You were the figure everyone was looking at during that live and present performance. It’s interesting thinking about that “in the flesh” presence juxtaposed to the live, however mediated, place of your body and what you presented last month.

Autumn: I feel like I have an opportunity to control the text a bit more, write something, work the text, and recite it. In The Length, I didn’t use spontaneous or improvisational speech.

Jasmine: When I teach performance art, I often teach about live performance as ephemeral. But that whole concept is differently framed now. How are you thinking about liveness and ephemerality, especially amidst physical distancing?

Autumn: I still feel like there is no substitute for the moment, even if it is on Zoom. Maybe we have the video documentation, maybe we don’t. We’re still relying on being present.

In terms of ephemerality, I’m still working through how to think about that.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here