The “Next Wave” of Theatre? Reflections on Avant-Garde Adaptations

The US economy may be (mostly) stable again for the moment, but that hasn't halted its interest in one European import: avant-garde theatrical adaptations. These productions take an old, perhaps even familiar text, and present it in a way that breaks free from all tradition and conventional readings. They aren’t necessarily new, but their popularity seems to be surging.

One American establishment has latched onto these productions perhaps more than any other—the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). This past fall, BAM presented its annual Next Wave Festival and among the more prominent productions were at least three avant-garde adaptations: in September, Phaedra(s), conceived/directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski; in October, Letter to a Man directed by Robert Wilson; and in November, Kings of War directed by Ivo van Hove. These productions utilized the texts of a Greek myth (and various works inspired by it), the diary of a schizophrenic dancer, and five Shakespearean(/Marlovian?) histories respectively. Despite being highly different in content, the intentions behind the productions were strangely similar. They articulated an emerging aesthetic of theatrical art where originality is sacrificed in favor of irony, surface meaning is discarded as false, and even technological advances can’t turn our heads away from the specter of the past.

Artaud and Cruelty, Postmodernism and Defeat

But before discussing these productions, I’ve found it that it’s most helpful to draw on two ideological thought systems to make better sense of what is being seen. The first: the ideas of French theatre theorist Antonin Artaud (1896–1948). Branded a pariah during his lifetime for his bold thoughts, confrontational style, and insurrectionist politics, Artaud best articulated his unique vision for theatre in his seminal essay "No More Masterpieces.” In it, Artaud advocates for the establishment of a "Theatre of Cruelty" where violent images, hypnotic sounds, and epic, yet surreal storytelling are utilized to shake the audience to their collective core. The term "cruelty" was chosen not because Artaud believes mankind to be cruel per say, but because as humans we are powerless, and therefore our very existence is cruel—in Artaud’s own words: "Nature mocks at morality…the sky can still fall on our heads.” But before reaching these conclusions, Artaud comments on the nature of masterpieces, and how their constant presence in our artistic consciousness is a great hindrance to our cultural development. Artaud writes:

...an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives…all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered…a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and…the theatre is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice.

A theatre living in the past becomes nothing short of a museum—a place of great knowledge, perhaps, but a place of no danger, no risk, no life.

Even if they have nothing else in common, these avant-garde adaptations (or AGAs, for short) seem to be obsessed with that last statement. Most theatrical works are extremely specific to the time in which they were created, but Artaud and his devotees argue that to continue studying or producing those works in their intended way does not keep them alive, but rather exhibits their fossil. A theatre living in the past becomes nothing short of a museum—a place of great knowledge, perhaps, but a place of no danger, no risk, no life.

So why do these productions seem to be looking backward when they market themselves as moving forward? This brings me to the second thought system: Postmodernism. Postmodernism encompasses many aspects of contemporary Western thought, but one sentiment captures the essence completely: defeat. Defeat by the ultra-powerful forces of greed and inhumanity, and the ultimate defeat of mankind (and through its extension, art) to have real power over existence. Already this seems to echo Artaud's words, and yet it goes even further. All the AGAs mentioned seem to begin from an embrace of aesthetic defeat—if there was hope for something new in art, wouldn't they try it? But they inevitably find no way to advance, so they retreat into the past, trying to cling to the tiniest morsels of meaning that have survived the ages.

Postmodernism is also intensely interested in the role technology plays in our contemporary world, and how it has irrevocably altered our modes of sensation, perception, and communication—not to mention the ways we view identity, information, and power. Are we most ourselves when we’re harnessing a digital persona, or when we interact physically? Does the digital world give us greater anonymity, or are we more exposed (and exploited) than ever before?

Ivo van Hove’s Kings of War

One avant-garde adaptation in particular had a keen interest in how technology can help us make sense of our primal lust for power: Kings of War, Ivo van Hove’s ambitious reimagining of Shakespeare's Henry V, Henry VI (Parts 1–3), and Richard III. Van Hove has gained notoriety in recent years for his intense interest in reinterpreting classic works, from Antigone to Angels in America to Arthur Miller (his direction of the latter’s A View from the Bridge and The Crucible were highlights of the 2015–16 Broadway season). With Kings, Van Hove sought to strip down Shakespeare’s artful language and complex plots to delve deeper into the scheming, often savage motivations that characterized the nobility of fifteenth-century England.

The production is a truly multimedia experience as it incorporates both live and recorded video (as well as projected images), displaying them on a large screen for the entirety of the production. Simultaneously, heavily fractured versions of the texts are being played with on stage. The use of video forces the audience to confront the large playing space in new ways (a war room/royal chamber, intricately designed by Van Hove’s partner, Jan Versweyveld), while doing something quite novel. It adds to the space; the camera often followed characters when they retreated to “backstage” hallways. These fluorescent white spaces were ingeniously used for many of the plays monologues, offering a kind of reverie from the rising tensions of the war room. Furthermore, the utter blankness of these hallways allowed the characters to figuratively paint them with their desires, doubts, and despair. For instance, when the young Henry VI delivered his “shepherd” monologue, the camera followed him down one of the hallways and revealed an entire flock of living, breathing sheep—calmly wandering through the corridor as if it were a lonely prairie.

Aside from the creatively constructed conflict inherent in the text, Kings of War also mines for conflict in more abstract arenas—i.e., the conflict of theatre with film, the visible stage with the obscured hallways, the physical with the digital, and the real with the dream. Indeed, this massive sense of dichotomy is a hallmark of postmodernism, in which individual consciousness is often fractured into less distinguishable components or personae—e.g. private and public, the human being and the online profile, and the original and the copy. Life has become so rife with paradox that it becomes impossible to survive as a singular, genuine individual.

Krzysztof Warlikowski’s Phaedra(s)

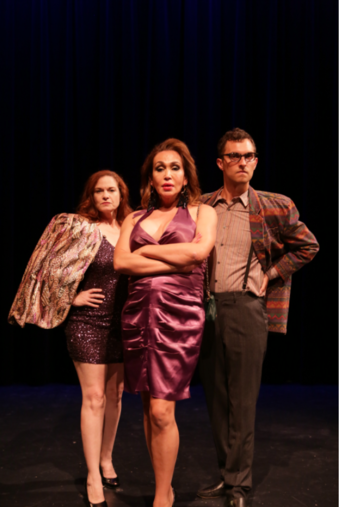

The paradox of surviving as a singular individual is further explored in Krzysztof Warlikowski’s Phaedra(s). The titular queen has been fractured not into two but into three (even the show’s very title hints at a blurry fracture). For those who may be rusty on their Greek mythology, Phaedra was the second wife of Theseus who brought ruin to herself, her family, and her country when she fell madly in love with her stepson Hippolytus. In this production, Phaedra (played with extreme dedication by Isabelle Huppert) and her disastrous fate is played out in three separate ways based on three very different sources: a madness-driven text by the Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad, a cruelty-driven play by the English playwright Sarah Kane, who committed suicide when she was twenty-eight, and a humor-driven essay by the South African writer J. M. Coetzee (Jean Racine’s monumental Phédre is curiously absent). The play bombarded the audience with fantastic images of an anthropomorphic dog in couture clothes, an exotic dancer swinging her hips with increasing speed, a character describing a murder scene while having sex, not to mention provocative film clips from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the film Frances, about Hollywood star Frances Farmer who was involuntarily committed to a mental hospital, and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema. None of these texts are used exactly as they were intended, but I was particularly interested in the use of Kane's, which is the only one of the three with a notable history on the stage.

Like Sarah Kane herself, this vision of theatre is heavily influenced by Artaud’s sensibility; stage action and text work together to amplify dread and jolt the audience’s attention. It was written to be cutting-edge theatre in 1996, but even that must have felt too long ago for Warlikowski, who reinterprets Kane's (and the ancient Greeks') penchant for orgasmic violence in a much less direct fashion. A prime example was the final scene of Kane’s Phaedra’s Love which is rife with terrible cruelty that would make Artaud smile in his grave. Characters are raped, disemboweled, murdered, and devoured by vultures all in front of a disturbed, yet rapt audience. Instead, in this production, all of the relevant characters gathered at the center of the stage, sat down and loosely mimed the action while Phaedra calmly read the stage directions from the original text.

These kinds of choices, which spit in the face of a writer's intention, lead me to the next postmodern feature of AGAs: irony. Phaedra(s) is filled with these deep notions of irony, where Warlikowski seems to find a twisted pleasure in asserting a vision in half-jest to juxtapose what the writer presented in earnest—like a child with a coloring book who, though they color inside the lines, chooses to make the ocean black, the sky brown, and a verdant field the hue of blazing inferno. To do this is to show how futile a writer's attempts to express really are—when anything can mean anything, everything must mean nothing.

The Revisionism of Robert Wilson

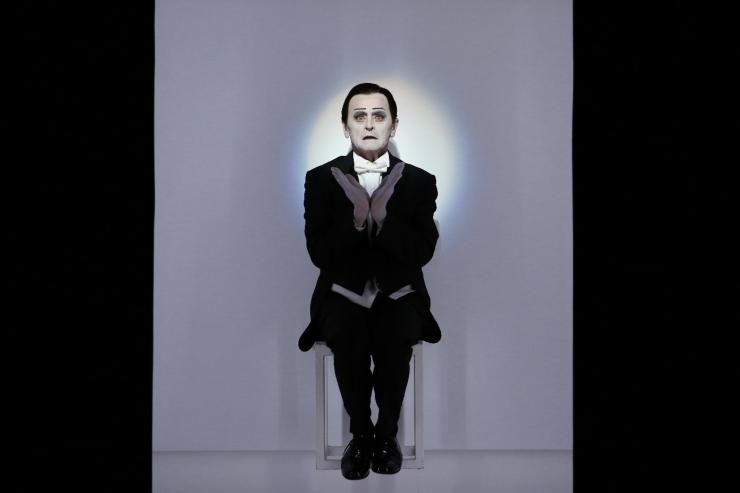

Perhaps no theatre artist has mastered this quality of revisionism better than Robert Wilson, whose works continually examine the past in grand, yet bleak terms. His latest production, Letter to a Man, tackles the later personal writings of deceased Russian dance legend Vaslav Nijinsky, portrayed by living Russian dance legend Mikhail Baryshnikov. While Nijinsky was a ballet star in the first two decades of the twentieth century, this play examines him during the 1940s when his abilities (and happiness) have long since deserted him in the wake of a difficult battle with schizophrenia.

Of all the productions mentioned thus far, this one gave its text by far the most attention. Language breaks down to such a point that the “meaning” behind words is often jettisoned in favor of establishing a certain verbal music that can’t easily be described. Through their constant repetition, phrases like "I am not Christ, I am Nijinsky," and "I understand war because I fought with my mother-in-law" become hypnotic counterpoints to images of upside down chairs, giant chickens, and phantom scarecrows. We quickly forget that these are the private thoughts of a man in complete mental disarray. Again, my mind wanders back to Artaud, and specifically his maxim on the use of sound: “Sounds…are chosen first for their vibratory quality, then for what they represent.” The implication is that “meaning” is not enough and future modes of expression must make use of that which cannot be articulated, or analyzed.

This production (and others) seem to imply that we’re all living in a catatonic state…we can only muster enough energy to glance backward. …Nijinsky finds a bleak comfort in revisiting his memories, and in the theatre, perhaps we find the same comfort by restaging memorable works of the past.

But aside from the curious, ironic attention to language, this production mostly made me think about nostalgia. The “man” referred to in the show’s title is ballet producer extraordinaire Sergei Diaghilev, under whom Nijinsky’s career flourished and his heart expanded. Large portions of the play examine their professional and romantic relationship in the 1900s and 10s, and there was even a recurring light/sound motif of sharp, transitionary moments inspired by vaudeville which further returns Nijinsky (and us) to the early years of the century. When Nijinsky is presumably in the “present” during the play (the 40s), the mood is gloomy, dark, and deeply empty.

Here is where I see a massive metaphor, which may or may not have been Wilson’s intention. Nijinsky enjoyed great acclaim, found artistic success, and experienced great love only to lose it all to the onset of his schizophrenia (among other personal problems). The rest of his life was spent in a stale marriage where reflecting on the past became one of his sole occupations. Is Nijinsky a symbolic figure, standing in for Wilson himself? For the entire theatrical form? For our twenty-first century existence? Just like Nijinsky, this production (and others) seem to imply that we’re all living in a catatonic state—whatever passions and talents we had have left us. And in our powerlessness, we can only muster enough energy to glance backward. Like those living with schizophrenia, the line between reality and illusion is blurred to an unimaginable degree. We can’t be sure of anything we perceive. Nijinsky finds a bleak comfort in revisiting his memories, and in the theatre, perhaps we find the same comfort by restaging memorable works of the past.

But it’s possible I’m overthinking it. Maybe these productions just wanted to be edgy, controversial, or had no new ideas whatsoever, so reverted back to old ones. Maybe they’re inspired by today’s “brand”-obsessed culture and saw greater financial success in presenting something with name recognition. Maybe all or none of these things. Regardless of the intentions, my own experience has found that avant-garde adaptations, in spite of their individual approaches, ultimately find greater strength in darkness than in light. But that strength is quite affecting (and at times, very beautiful) so it must contain a great degree of truth. If anything has become clear recently, it’s that the world can be a whole lot bleaker than we often imagine it to be.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Artaud’s call to break down the masterpieces to reflect the

cruelty of our existence on earth due to our lack of power is

thought-provoking. He adapts old classics in a way that picks their very

structure apart as part of the avant-garde movement. Derek, your viewing

avant-garde performances of classics as an example of post-modernism, as an

acceptance of not being able to move forward, of accepting being stuck in the

past and its static stories makes me think about how storytelling goes in circles.

In trying to create something new, we are always reliant on everything that has

been written and played before us. Our art depends on art that came before us.

This piece covered in detail how technology is used in various productions and

opened up many possibilities for me. It makes me think about how multiple forms of media could enhance a storyline in live theater.

The line “...an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives…all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered…a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and…the theatre is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice,” resonates with me because of how accurately it represents life. I have learned that if I see a play or a musical several times, it will be different every single time. And I love that. I love knowing what line will come next but not knowing how it will be delivered or if the audience will laugh at it like they did the night before.