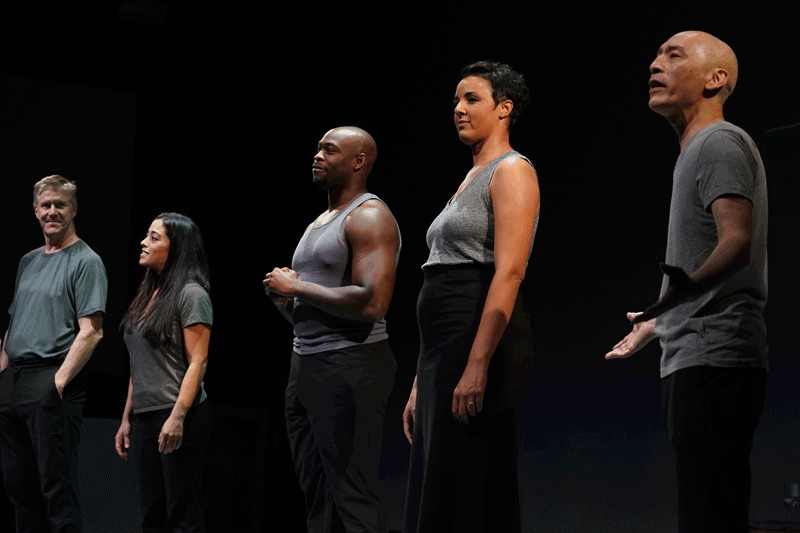

Last fall, I attended a performance of Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 at Signature Theatre in New York City. The emotionally evocative piece of documentary theatre chronicles the events immediately preceding and following the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Though the show's creator, Anna Devere Smith, originally presented the piece as a solo show, this particular production featured a multiracial cast of five.

As one might expect given the subject matter, this production insistently chipped away at audience members’ capacity to witness violence. The production captured this perhaps most gruesomely when the twin screens on either side of the stage rolled security camera footage of a beauty store owner fatally shooting Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old girl, in the back of the head. Foreseeing what was coming, I closed my eyes and covered my ears until the audience’s collective gasp signaled that it was safe to reengage my senses.

This moment of the production left me with a distinct sort of confusion. On one hand, there was a morbid prescience of rolling black-and-white VHS tape of a Black person’s violent death some twenty years before cell phones began to fulfill that purpose. And yet, when we live in a world where the images of dying Black people do numbers on the internet, what does forcing an audience to add to their mental catalog of violence achieve? When we remember that New York City audiences are disproportionately white, who stands to lose?

The whiteness of the audience was then brought into full relief as the house rang with laughter directed at the East Asian accent of one of the characters. This actor had not said anything particularly funny. What’s more, given that this was documentary theatre, one can assume that the actor was rendering a true-to life rendition of a real-life person. This precious moment of comic relief in this two-and-a-half-hour meditation on the basest instincts of human nature rested on this person's perceived otherness.

When we live in a world where the images of dying Black people do numbers on the internet, what does forcing an audience to add to their mental catalog of violence achieve?

And now, to this day, my experience of the production—the text, the performances, the design elements—is overshadowed by my experience of being in the audience. That moment was merely a harbinger of what has now become a plethora of unfortunate experiences stemming from being one of few, if not the only, Black person in the house. To throw a further wrench into things, I act; if I intend on having any career at all, it will likely be built on me performing for audiences that bear little to no resemblance to me and my family.

Since then, I have been trying to make sense of the split-screen experience of producing a racialized story for a deracialized audience. And in this regard, The Souls of Black Folk is the gift that keeps on giving. In it, W.E.B. DuBois (“The honor, I assure you, was Harvard's”) articulates the concept of double consciousness:

“The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder”.

Speaking from a sociological lens, DuBois argued that African Americans are in a constant state of split focus. Black folks understand themselves both as individual members of the African diaspora, each with a unique point of view, and extrinsically as the targets of intense hatred and derision.

To bring it to our own pop culture discourse, when somebody tweets that Chris Rock deserved to be slapped by Will Smith for disrespecting Jada, but then someone else tweets that Will slapping Chris in front of all those white people will set Black people back, that is double consciousness (and respectability politics) in action.

And if art is merely a reflection of the society it exists in, then surely Black folks in the theatre are not exempt from carrying these “two unreconciled strivings.”

But whether you are a Black actor playing a Black character or a Black actor who has made your character Black transitively, the audience perceives your Blackness on stage.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here