The Paradox of Repetition

Presented to the New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies December 17, 2010

When I was twenty I thought I might become a psychiatrist, and to that end spent an unhappy year at Harvard Medical School, where I confess I spent most of my time directing plays before dropping out. But I’ve retained my deep fascination with human behavior, and I have always felt that theatre is another way of studying how and why people behave the way they do. Today I’m speaking to you with great interest, but no expertise in psychology or analysis. What I know about repetition compulsion comes mostly from my friend, the psychotherapist Marc Kaminsky and the readings he suggested to me. My perspective is that of a theatre person.

My main mentor in theatre was Joseph Chaikin, a seminal figure in American Theatre, who in the sixties founded The Open Theater. In a brief essay of his titled, “Notes on Acting, Time and Repetition,” Joe said:

The main thing in growing old is how repetition affects us. We walk in and out of doors each month. … We make love more times. We endure more outrage. We witness more of what seems meaningless. We discover ourselves caught in a new trap in an old way.

…For some (repetition) deepens and for others it hollows out experience.

The writer, Samuel Becket called habit, “the great deadener.”

Repetition, and habitual activity, brings to mind drudgery, boredom, dullness, stasis, a rut. The worker in an assembly plant; the bore who repeatedly tells the same story; the aspect of ourselves that responds to another person in the same way we have done countless times before.

Art functions to break our habitual ways of experiencing and perceiving. The Russian literary theorist, Viktor Shklovsky, said the task of art is to make the familiar unfamiliar.

Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. …The thing rushes past us, pre-packed as it were: we know that it is there by the space it takes up, but we see only its surface. This kind of perception shrivels a thing up, first of all in the way we perceive it, but later this affects the way we handle it too… Life goes to waste as it is turned into nothingness. Automization corrodes things, clothing, furniture, one’s wife and one’s fear of war… And so that a sense of life may be restored, that things may be felt, so that stones may be made stony, there exists what we call art.

I shall return to strategies that theatre artists have used to make the “familiar, unfamiliar” but first we must acknowledge how difficult it is to break habit and convention. Kafka tells the following parable.

Leopards break into the temple and drink the sacrificial chalices dry; this occurs repeatedly, again and again; finally, it can be reckoned on beforehand and becomes part of the ceremony.

In early nineteenth century French theatre there was rarely any furniture on stage. Chairs and tables were painted on the wings and drops. Furniture was useless because the actors stood in a semi-circle around the prompt box. In the early 1850s, Montigny revolutionized blocking by putting a table and a chair directly upstage of the prompt box in order to force actors out of the semicircle into more lifelike positions. This created a frenzy among actors and audiences alike. The real intruded on the sacred space of the stage. (The leopards had entered the temple.) And, of course, by 1870 the use of furniture lost whatever shock value it had.

Art functions to break our habitual ways of experiencing and perceiving.

In 1968, the actors in the Open Theatre’s The Serpent spilled out from the stage into the audience. At the time, this seemed shocking—a violation—but, after this type of interaction was repeated in many avant-garde productions, it lost whatever power it had.

In theatre, repetition has positive meanings as well. The French call a rehearsal, “repetition.” It’s what we do to put on a play, or any performance—music, dance, opera. To rehearse is to practice. We practice scales, we practice doing pliés, we practice speaking lines of Shakespeare. You, as therapists, have a practice as well. You practice your science and your craft in sessions with your patients. For the artist and therapist alike, this practice improves with repetition, i.e., experience, but unless one fills this “practice” with awareness and insight, “practice” runs the risk of becoming mechanical.

In traditional Asian theatre, the novice learns by copying and repeating gestures, inflections of speech, dances, and songs that have been handed down from master to student for generations.

Noh and Kabuki is based on the idea of “kata.” A kata is a fixed convention of a performance which has been passed down by the teacher to the student, and which must be faithfully copied in every detail. Each role in a play has a particular kata, which prescribes every single movement, vocal intonation, costume detail, and nuance of interpretation. As a consequence, all performances are identical, and essentially unchanged from generation to generation. In this sense, the Japanese use of kata resembles the Western system of classical music, or classical ballet. From An Actor Adrift, Yoshi Oida.

How can these ancient forms, based on imitation and repetition, maintain such great vitality? For one thing the score that is handed down has become honed and polished to a point of great clarity and evocative power. What remains over the generations are those images and texts that remain vital for their audiences. The vague, the superfluous, the dross fall by the wayside. So what is left is a perfect vehicle that conveys in the most powerful way the story of the play to the audience. The performer’s job is to step into his role—to inhabit the costume, the masks, the steps, the words and the inflections of their masters so that the character and play become alive again.

As an artist I don’t like to repeat myself, but I enjoy repetition in art. Especially when it is embedded in variation. Then I get both the pleasure of recognition and the pleasure of surprise. I encounter an old friend—a word, a musical phrase, or a visual image—in a new guise.

Moreover, their performances are not mechanical. Even though the external forms are exact repetitions of what had gone before, the great artist fills these forms with their intelligence and imagination. In the Kabuki theatre, there is a gesture which indicates “looking at the moon” where the actor points into the sky with his index finger. The Japanese actor, Yoshi Oida tells of the saying of an old Kabuki actor “I can teach a young actor the movement of how to point to the moon. But from his fingertip to the moon, that’s the actor’s responsibility.” Yoshi goes on to describe two different actors performing this same gesture. “One actor, who was very talented, performed this gesture with grace and elegance. The audience thought: ‘Oh his movement is so beautiful!’ Another actor made the same gesture. The audience didn’t notice whether or not he moved elegantly; they simply saw the moon.”

In the Open Theater we also had an aesthetic of distillation. We sought to find the essential gesture, phrase, sound, body shape, or rhythm that conjured up a realm of experience. Joe Chaikin called these “emblems,” distilled events that resonate and stay in the observer's mind. In theory, the emblem is a perfect form, one that retains its vividness and communicative power after countless repetitions. Our challenge as performers was to inhabit the form, not as a frozen entity, but as a vital shape that is responsive to the ever-changing currents between the performer and audience. Once we discovered the form, we could find a multitude of subtle variations within it.

The great German playwright and director, Bertolt Brecht used repetition in a different way. It was a tool of what he called Verfremdungseffekt or Alienation-Effect. Influenced by Victor Shklovsky, Brecht used alienation to make the audience take notice, to lift an event out of the flow of the habitual, and show what was extraordinary about it. In his essay, “The Street Scene—A Basic Model for an Epic Theater” Brecht likens his theatre to the performance of witnesses to a street accident who are describing what happened. Brecht says, “The street demonstrator’s performance is essentially repetitive. The event has taken place; what you are seeing now is a repeat.” The demonstrator says “the man was stepping off the curb like this, and then the truck hit him.” He repeats the action, perhaps a bit slowed down, so we know that just as the man stepped he was looking the other way. And then repeats it again so he is sure we understand. “He alienates the little subincident, emphasizes it’s importance, makes it worthy of notice” In Brecht’s theatre, this “alienation” of the action has a social function. He’s doing it, because he is establishing blame, he doesn’t want us to miss this detail because it is crucial to his argument. He doesn’t want it to “rush past us, pre-packed.”

One can also make “the familiar unfamiliar,” “the stone stony” by putting it in a different context. If you put a pile of bricks inside an art gallery, you are inviting the audience to regard these bricks differently then they would regard the same pile if they passed it on the street. Or if you take a fire extinguisher off the wall of a corridor in the gallery and put it on a pedestal in the center of the gallery, the fire extinguisher takes on a different significance.

In the work of my company, The Talking Band, we will often take a motif—piece of text, a visual image, a musical phrase—and repeat it in a different context. This juxtaposition of the motif against something new gives the repeated motif new life and meaning.

(Demonstrate a choreography of several physical shifts: pick up a glass of water, drink, then put glass down, take deep breath, wipe brow, look to my left, take a few steps in that direction, return to the lectern, again look to the left, look front, take a deep breath, again pick up the glass of water, drink, put down. Then exactly repeat this choreography twice, each time accompanied by different music: “Dead Already” by Thomas Newman and “Star Crossed Lovers” by Duke Ellington. Ask the participants how did the music shift their perception? What “story” did they see?)

In an actual theatre work, or a musical composition, a repeated motif takes on resonance not only because it is juxtaposed against something different, but, also, because we have experienced a great deal between the last time it appeared to us and now. In Schubert’s C Major Quintet we hear the musical motif in two minutes into the first movement. We hear the motif—with different modulations, tempos, harmonics, dynamics—interspersed through the next twelve minutes of the movement, and by the end we have gone through a wide range of emotions, so when we encounter the motif towards the end we are a changed person meeting and old friend in new circumstance. There is great pleasure in this. In King Lear, Shakespeare repeats images of sight, blindness, darkness, and light numerous times until the many instances weave together into a great central metaphor of the play.

Some of you may have seen Panic! Euphoria! Blackout, a show that my company The Talking Band presented. The playwright Ellen Maddow uses a ring form for the structure of the play. It is an archaic structure used in such texts as The Iliad and the Book of Days. The ring form, describes a journey that ends where it begins. It tells a story up to a turning point, then reverses itself and returns to the beginning. Unlike in a conventional drama, which moves from a development to a climax to a denouement, the events in the second half of the play—i.e., after the turning point—are a mirror image of the first. And so one hears and sees many things repeated but with new meanings because of their position in the play.

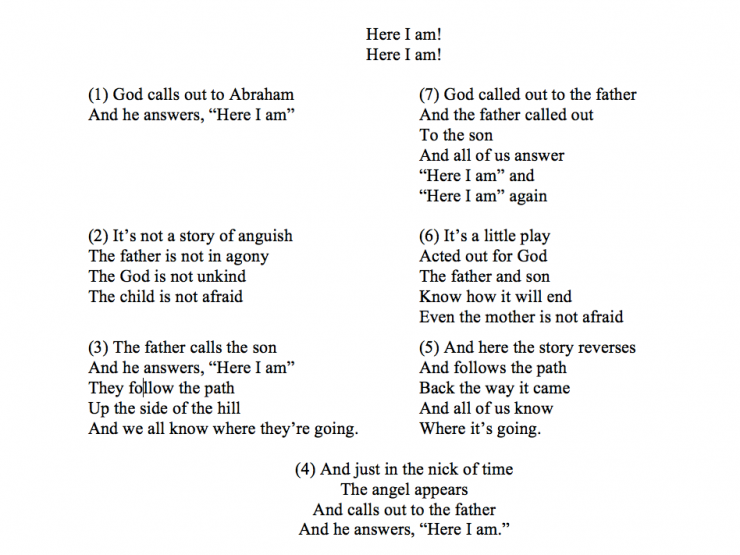

The first words spoken in the prologue of the play are “Here I am.”

The next time we hear these words is thirty minutes into the play. The three characters, Silverman, Ruth, and Rubin, who are traders and moneylenders, have gone to a river on Rosh Hashanah to empty their pockets of the year’s schmutz. And as he does every year on this occasion, Silverman recounts the story of Abraham and Isaac.

According to the scholar Mary Douglas the disturbing story of Abraham and Isaac is best understood if we realize it is in ring form. Its intended audience knew how the story would end from the start.

This is how Ellen tells the story, so you can visualize how the structure works:

In this brief telling, we hear the phrase seven times. When we hear the words they are the same but not the same. They are colored by the journey that Abraham, Isaac, and we have taken.

When we next hear the words in the play, Silverman has been betrayed. He has left, and come back, with a new persona—Bitterman. His friends welcome him and he answers, “Here I am.” He retells the story of Abraham and Isaac but from a very different perspective.

When I was a boy, I felt like the boy.

Abraham was my father.

We walked up the hill like matinee idols.

The bushes and rocks were paper-mache and paint.God was watching

With his thousand butts

In a thousand faded velvet seats

His fingers fussed with candy wrappers

His eyes were blinking, blinking in the artificial light.When I became a father, I thought I was the father

My beard stuck on with spirit gum.

Tiny Isaac, rouged and lipsticked

Held onto my hand as he sang a sweet farewell.But now I know who I am

Just now, I understand what I am

I am the sheep, found in the bushes, offered up

Burnt to a crisp, forgotten on a pile of stones.

No one tells the story of the sheep.“Here I am, and here I am again”

It’s not a good story.

All what’s left is four yellow teeth

and a pile of sticks that stink of mutton.

No one is listening, God has gone home.

As an artist I don’t like to repeat myself, but I enjoy repetition in art. Especially when it is embedded in variation. Then I get both the pleasure of recognition and the pleasure of surprise. I encounter an old friend—a word, a musical phrase, or a visual image—in a new guise. The special pleasure in hearing a Bach fugue or a Mozart theme and variations is that the formal structure is clear yet I am surprised and delighted to hear a familiar motif reappear in a place and manner that I did not anticipate.

In a therapeutic session, repetition is a symptom that needs to be recognized by the therapist and, ultimately, by the patient. What the therapists listens for is certain motifs—memories, phrases, or behavioral responses that repeat. What is being repeated is not always clear at first. Because the template may be the same but it appears in different context with different tonalities. So the therapist must have an ear for the various tonalities. If the therapist listens attentively, but without preconceptions, these motifs take on new meanings depending on their ordering and their context. And suddenly, some new understanding about the meaning of these repetitions may leap out to the therapist. Marc Kaminsky suggests that the therapist’s sensitivity to the permutations of these repeated motifs, and his or her insight into their underlying meaning, is what is meant by “free association.”

As therapists you recognize there are many aspects to repetition—it may be a symptom, a means of working through trauma, or as pathology. We also know there is pleasure and comfort in repetition. Although, as one of Marc’s patients put it, the comfort may be in coming back to one’s “ cozy little hell.”

In both therapy and theatre what distinguishes a repetition that deadens and “hollows out,” from a repetition that is potentially useful and creative, is the awareness of the participants—the patient, the therapist, the artist, the audience. Repetitive formulations become alive when imbued with a particular consciousness and purpose—to show the moon: when they allow one to perceive or express an action or a word in its uniqueness so that one understands—perhaps makes a judgment (as in Brecht’s theatre)—or feels something broader and deeper about a relationship, and event, or the world.

A patient will hopefully not only be able to recognize his or her repetitive behavior but, also, see it from a new perspective, which brings new understanding of the causes, and some relief. The audience appreciates there is something extraordinary in a particular motif, metaphor, or gesture. After a powerful performance, I as an audience member go out onto the street and experience the everyday world around me transformed. Last year I went to a production of The Tempest. The play works and reworks in text and visual images themes of injustice and revenge, but it ends in forgiveness. And I went out of the theatre feeling the real possibility of forgiveness, even in these embittered times.

Before I end, I’d like to say a few words about character. Character is a subject that absorbs both psychotherapists and theatre artists.

There are innumerable plays about characters who are stuck in repetitive patterns. To mention only a few examples, George and Martha in Edward Albee’s, Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf; Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire, and Amanda in The Glass Menagerie; most of Chekhov’s characters. There are other characters who only partly escape these patterns like Tom in The Glass Menagerie. He frees himself from his stifling family but not the painful memories of them. And then there are a few great tragedies in which characters are transformed through harrowing events. King Lear is one of the great examples of this. I personally am drawn to creating plays that offer the possibility of transformation. Especially now, when I fear that many people increasingly feel they are stuck in their situation and can’t envision alternatives.

Aristotle, in his Poetics, defined character as “habitual action.” In other words, what people do repeatedly defines them. On the other end of the spectrum, the twentieth century Russian theorist, Bakhtin, in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics says that the characters of Dostoevsky are “unfinalized.” They are in process, most usually in crisis, and one cannot predict how they will act because their behavior at one moment may be totally different from their behavior in the next. Playwrights generally view characters as finalized: they may reveal something we didn’t know about them initially (or they didn’t know about themselves), or they might change some aspects in the course of the play, but basically they are more in line with Aristotle—they are known by a pattern of behavior.

Elizabethans saw character defined by humors—people were choleric, melancholy, phlegmatic, or sanguine depending on the predominance of yellow or black bile, phlegm, or blood. Brecht, a communist, saw character defined by class, and, since people were formed by social and economic forces, they could change if the social conditions changed.

How you define character is crucial to your belief in whether people are capable of transformation, and if they are, what are the means of bringing about this transformation.

I think we contain many selves. Some come to the fore more than others. For many people most of these selves are never cultivated, explored, or given voice and therefore wither. It’s an actor’s job to explore these various selves. By playing different roles one finds a correspondence in the characters one plays and aspect of one’s own personality. When I taught beginning acting at Princeton University, many of the students were probably going to become lawyers or investment bankers, and I viewed my task not necessarily to make them actors, but to give them a chance to know these other selves.

As I said at the beginning of my talk, I have no scientific expertise, so I realize I have chosen to address you as fellow artists, which I believe in your practice you are. I now welcome your response.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here