Elaine: I have to take Brad because of his epilepsy and, I’m the person who’s been on the phone with the residency and said, “I know you have an accommodation for parents, and I‘d like to tell you about my situation.” And then I explain that my husband has epilepsy from a stroke, and we don’t anticipate a problem. Then, outside of San Francisco I had this really great residency, and one or two days before we left, Brad had a massive seizure. And I was trying to get the ambulance to find this little room we were in at the retreat in this rural area in the middle of nowhere. It all worked out. We got him to the hospital but I felt guilty about him having a seizure while we were away from home.

There are a lot of things that I don’t apply for. The virtual world has been great for me. It’s been good for being able to develop work. It was really exciting to do Halsted with Arizona Theatre Company virtually, just to have that chance to workshop the play with amazing people. Virtual theatre is really generous for people with disabilities and people who can’t go to the theatre anymore because of age or maybe they can’t get transportation. There’s a whole digital life that we can continue to develop as advocates, not just for ourselves, but for the greater community. My mother used to be a subscriber at three or four different theaters in Portland, Oregon. And now she can’t really go, she’s like eighty-nine. This pandemic has forced us to think about how we do things, how we take care of people, how we don’t take care of people.

The other day, I was reading an article that said COVID attacks the part of the brain responsible for empathy.

Carlyle: Really?

Elaine: What a tragedy.

Carlyle: How ironic.

Elaine: That might explain a lot about what’s happening in this globe. Why don’t we care anymore? I remember our wheelchair story. The Chicago hospital sent us home with a wheelchair, and we get home, and Brad grunts and points at it. I’m like, oh, he doesn’t want that in his house. And I’m like, you understand if I give that wheelchair away, they’re never going to give us another one. That’s the only one the insurance is going to give us.

Brad said something, which I heard as, “I want that out of here now!” So, I took the wheelchair out of the house and donated it to a local thrift shop. Later when he could speak more, he said that he knew if he sat down in that thing, he would never stand up again.

I had thought that working on the play together was maybe a way to bring her back into the world, bring her back into the theatre, which has succeeded to some extent.

Catherine: That’s very, very similar to what happened with John, that endless fight for laying the body, putting the body down into the chair. Also, there are different kinds of chairs and the really good one, the one that’s actually going to be really useful in his case, is not at all covered by health insurance.

So, it’s always those battles. I was interested, Carlyle, in what you said about the idea of dysfunction, that it has to be on purpose on some level. It ties into the issue of accessibility. It happens in so many ways, with the sidewalks and with bathrooms and with going to the theatre and just, like, you name it. I mean, how complicated is it to make things accessible? And yet it’s an endless dysfunction.

Carlyle: Basically, a lot of it doesn’t make any sense. But good people make exceptions, make a difference. Barb, she was starting to walk, and then she fell and broke her hip. She’s always trying to be more independent. So, what do you do? Do you inhibit that or let her be as independent as she dares? But it’s a risk. I mean, that fall took her back. We’re just coming back from that now. That’s like a couple years. But your wheelchair story reminds me of how Barb’s old wheelchair was a box, an ugly thing and an effort for her to move herself around in, and she doesn’t want an electric wheelchair. Here in Minnesota, you have to go to physical therapy to get approved for a new chair.

So, we went to a physical therapist. And I don’t know, I think there was something about our relationship that she was sort of attracted to, as well as Barb wanting to show her that she can get in and out of bed by herself and do many things on her own. So, this woman recommended this wheelchair. It’s a manual wheelchair, but it’s freaking state of the art. One of the things is it’s not ugly, it’s not an ugly box. It’s got great ergonomics and it can turn on a dime. She can stay upright and move the wheel with one hand and maneuver around. It makes such an enormous difference in her quality of life.

Elaine: We don’t judge the chair. Not at all.

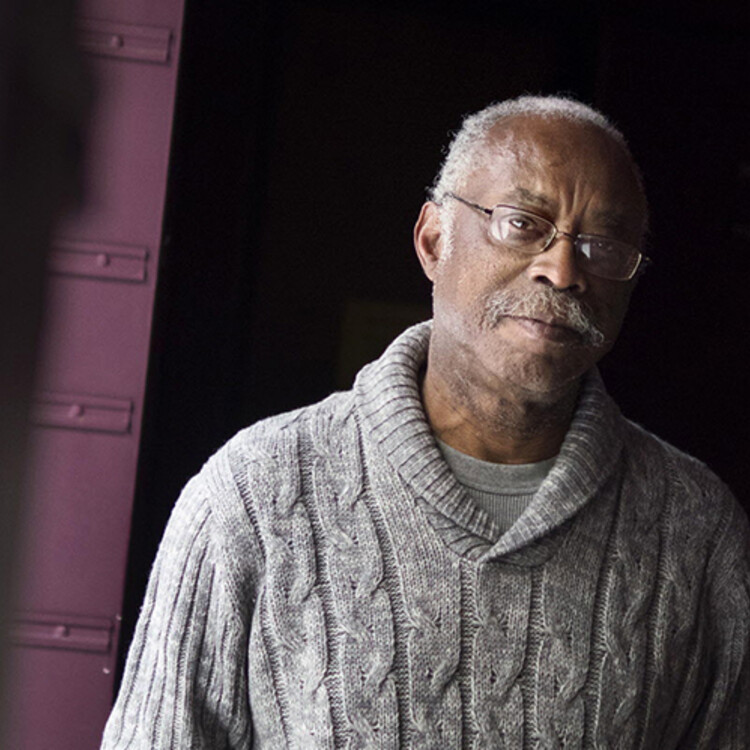

Carlyle: Where my play, A Play by Barb & Carl, was done at Illusion, the board chair is also the chair of the Minnesota Stroke Association. So, there was a lot of community outreach. Barb, a shy, homebody kind of person, suddenly became a bit of a celebrity, which she discovered that she actually liked. I had thought that working on the play together was maybe a way to bring her back into the world, bring her back into the theatre, which has succeeded to some extent. So there are things that I’m very glad to have in my life. I’m not very glad to have her disabled, but there are things that were otherwise not accessible to us. Just like what you’re saying, how we know each other, how we are together. That might not have been.

Elaine: I would say two things have really helped me in this journey. One is beginner’s mind. When I write a play, I try to approach it like I’d never written a play before. Just do whatever happens in the play that you’re writing. Let the play tell the story. And then the other thing is William Goldman’s famous quote “Nobody knows anything.”

Carlyle: “Nobody knows anything.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

What an enlightening conversation. Thank you Catherine, Elaine and Carlyle.

This is a very powerful article. As someone I love is dealing with an early Alzheimer's diagnosis, and while things seem fine, I am holding caretaking closely and pondering what I need to do.