Political Immersion in Roadkill and La Ruta

In July 2013 some friends on Facebook shared the video of actor and rapper Mos Def (who now goes by the name Yasiin Bey) undergoing a live torture reenactment of force-feeding at the prison in Guantanamo Bay. Directed by Asif Kapadi, it was made by the human-rights group Reprieve to protest conditions of such a procedure, which were described by US District Judge Gladys Kessler as “painful, humiliating, and degrading.” The video—endurance performance as a form of agitprop— is filmed at close range, and attempts to place the viewer on-site, as if one were physically present witnessing the medical assistants force the tube down Def’s throat and nostrils. Unable to go through with it to completion, Def eventually pleads with them to stop, weeping. The result is grueling and painful to watch; I myself could not get past the middle. Although I’ve long known about the US government’s force-feeding tactics at Guantanamo, Def’s reenactment, which sets up a real situation that provokes shock and disbelief, succeeded in raising my awareness and outrage at such “standard operating” procedures.

Two performances I saw this Spring: Roadkill at St. Ann’s Warehouse, conceived and directed by Cora Bissett with text by Stef Smith and Ed Cardona, Jr.’s La Ruta, directed by Tamilla Woodard at Working Theater, remind me of Def’s video for numerous reasons.

They employ experimental practices with straightforward agendas: they make art political and turn the political into art. They also seem to represent an increased interest in contemporary theatre that embraces this conflation. In doing so, they generate off-site and participatory experiences that move beyond sitting politely in the theatre, placing you in the midst of the action, as if you were really there. As opposed to Brecht's prominent Verfremdungseffekt or defamiliarization effect, which calls for emotional distance with a play's characters to raise political awareness most effectively, Roadkill and La Ruta deliberately maintained the fourth wall throughout the length of the performances, with the actors never breaking character the few times they did address the audience. On the surface, this emotional proximity would seem to be a return to the willing suspension of disbelief Brecht so abhorred as politically passive. But it is precisely by immersing us into the victims’ violent environments at close range, as if we were there, rather than witnessing the event afar from a darkened auditorium, that both these pieces achieve their political ends.

In doing so, they generate off-site and participatory experiences that move beyond sitting politely in the theatre, placing you in the midst of the action, as if you were really there.

Contrary to the more typical examples we might currently associate with immersive theatre practices predicated on audience circulation and the production of pleasure-seeking adventures such as Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More (2009) or Third Rail’s Then She Fell, these three works alter our perception of what it means to act once outside the theatre. In other words, their use of participation and immersive techniques are meant to engage us both artistically and politically, asking us to question our role and level of involvement not just inside the show, but to the social justice issues they present. And however negatively, a recent New York Times article (by Judith H. Dobrzynski) sees the current trend in the arts (“cultural institutions are offering participatory experiences available almost everywhere else”), these shows prove that within a tendency that often only seems to engage us, there are the few that successfully do.

I saw Roadkill in Brooklyn, three years after its premiere in 2010 at the Edinburgh Fringe. It is based on the true story of a girl from Nigeria whom Bissett met through her volunteer work, who at the age of thirteen was trafficked to Scotland and forced into prostitution for four years before she managed to escape. Described by The New York Times as “difficult to watch” and “impossible to ignore,” the piece was staged inside what seemed like an ordinary brownstone in Clinton Hill, but whose claustrophobic interior embodied an utter nightmare for the show’s protagonist Mary, played by the formidable Mercy Ojelade. Alongside Mary and her manipulative “auntie” Martha (Adura Onashile), we began the journey in the bus that took her straight from the airport to her new home. Wearing a white dress that in retrospect accentuated her innocence (it would later be ripped and stained with the blood that marked her loss of virginity), Mary enthusiastically talked to us about her hopes in the Big Apple, even proposing to babysit my children for ten dollars an hour. Upon arrival, in less than a matter of minutes, her passport is taken and she is viciously initiated into her new life: raped, scolded, threatened, humiliated, and forced into prostitution. All we can do is sit there, in horror, and watch as Mary, alone in her new red lit bedroom wearing a new black slip (a welcome gift from “auntie”), shakes in desperation, quietly hyperventilating.

In order to behold the devastating trauma that follows, Bissett immerses us in the midst of the action, recreating Mary’s gruesome experience for an intimate audience of twenty. We not only see Mary weeping, we smell the perfume in her room, feel trapped by her captors as they flagrantly walk past us (John Kazek plays the men in Mary’s life), and are invited to a cocaine-fuelled brothel party upstairs, where we see Mary chained half naked to a bed pretending to writhe in pleasure. At one point, when Martha is not looking, she whispers to some of us to please save her. In one particularly graphic scene, where Martha advices fourteen-year-old Mary on how to be penetrated from behind, one audience member suddenly got up, gasped, and simply fainted. (There was perhaps a 10 second time lapse before the actresses broke character, and quickly went upstairs. The stage manager immediately called 911 and the audience was dispatched outside. The woman got better and the show went on.) Indeed, the show’s immersive quality makes for chilling theatre. But perhaps what was most striking about Roadkill is how it mirrored our everyday apathy to the injustice that happens all around us. Amidst many “immersive” theatre experiences that highlight thrill seeking, this work challenged us precisely by surrounding us in a situation that is completely and utterly abhorrent.

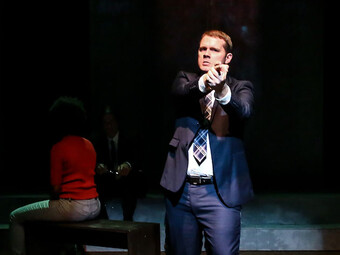

La Ruta (“the road”), which depicts the perilous journey of several undocumented immigrants smuggled through the border from Mexico to Texas, employed similar immersive techniques to Roadkill—placing fewer than thirty spectators in the midst of this dangerous passage alongside its protagonists, who get crammed, just like us, inside the trailer of an actual forty eight-foot truck. As soon as we begin (and I saw it on a hot and rainy night in the parking lot of the Snug Harbor Cultural Center in Staten Island), a man with a flashlight directed us to a tent with some wooden crates. The audience convened and before we knew it a tall woman named Raula (the head smuggler played by Sheila Tapia) was telling us to shut the fuck up (which yielded uncomfortable laughter for the elderly couple sitting next to me) and filed us one by one into the back of the truck. Once inside, seated in small cardboard boxes between the truck’s cab and the back compartment- where ‘the other’ illegal stuff was hidden- the engine starts and we learn the stories, dreams and hopes of these fellow travelers: the young and pregnant Irma (Zoë Sophia Garcia); the more experienced Mabel from Guatemala, trying to get back to her family (Annie Henk); and Francisco, the former gang member looking for a new start (Gerardo Rodriguez). The atmosphere turns ominous, and before the unrelenting Raula can drop off the “embargo,” the deal goes awry, a gunfight ensues, and the immigrants, like hundreds of border crossers per year, are left to die, most likely from the heatstroke caused by the frying Texas sun they never saw. As with Roadkill, we are part of the environment we are watching, dying with them inside the truck. This immersive staging, along with the sonic environment and video projections, was the strongest element of La Ruta, whose text I felt was too descriptive and explanatory, especially given the fact that we already had an overload of sensory material going on.

Off-site immersive theatre, as evidenced with these two works, has the potential to operate under committed ends, and not just be another gimmick to attract audiences. Moreover, what I find particularly compelling about both these productions is how they create collaborative production models that generate new audiences and forms of engagement outside the performance. La Ruta, like the truck that housed it, is a mobile performance that toured all five boroughs. When the show is over, we walk into an exhibition by Magnum photographers that documents the stories we have just witnessed. The Working Theater’s mission, which presented the piece, is to produce plays “for and about working people.” How transformative it would be to have US immigration officers step into La Ruta, so that perhaps they can experience what it’s like from the other perspective. St. Ann’s Warehouse and the British Council, who brought Roadkill to New York, organized The Roadkill Forum “to help eradicate the demand for human trafficking.” Coincidentally, both productions offered a passport to audiences as part of the program with information about what individuals can do to help.

In a recent article titled “On Immersive Theater,” Gareth White argues how this form of performance has a special capacity to create deep involvement. “We talk of ‘immersing ourselves’ in other experiences,” he writes, “—new situations, cultures, environments—when we want to commit to them wholeheartedly and without distraction.” Indeed, both of these productions aimed to highlight human suffering for straightforward political ends. They immersed us within the environment of its victims, rendering us voyeurs to such a spectacle. We are left to watch what we can now no longer ignore.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for this interesting and thoughtful examination of form, content, and their sometimes contradictory/sometimes aligned intentions and embedded ideologies...