Yaşam: As the name suggests, OpenSpace is “open” to experimental works. You produce in a unique space in Tbilisi, relatively far from the center. When you are producing, how does the space affect your production in terms of opportunities it offers or certain limits it imposes?

Davit: I grew up in the district of Tbilisi called Nadzaladevi, which means “the place where the disobedient live” based on the imperial legal term for the construction unauthorized by central authorities. I had to change two buses to get to the “city center” where the theatre school is located. It wasn’t just about the time or distance, but about the change in the communicative style with the place that I experienced during these daily journeys, my own daily psycho-geographical drifts. So, the performativity of space became material to me.

The Isani District where OpenSpace is located is one of the areas in Tbilisi that suffered most terribly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was centered around a major aviation plant located just down the road and the micromotors factory where we are now was part of its supply chain that defined the lives of hundreds of thousands of people who lived here. After the collapse of the Soviet system, these factories became irrelevant and abandoned. People still live here, but the meaning of the place has largely become obsolete. So, in our own humble way, we aspire to be a space that creates new relevant meaning here and now in the middle of these modern ruins of concrete. It’s also our statement against the imaginary cultural hierarchies of the city and the obstacles to access culture and expression that they create. Our neighbors are a punk bar, sewing production, garages, and the homes of ordinary people, not the downtown temples of bureaucracy and establishment. This is where we feel most at home to reflect on the change and dynamic of Georgian society in the media and forms that we create, which is the purpose of OpenSpace.

Yaşam: UNLOVE is a research project and the second performance of your “UN-” trilogy. What is your starting point in this trilogy?

While following the war and progressively repressive politics of our own government on our smartphones in real-time, we strove to reconnect with what being a human was.

Davit: The starting point of the “UN-” trilogy is my personal crisis that coincided with a crisis in the world at large. It just so happened that when the world entered the COVID crisis, I experienced a major transformation in my personal life as well, and that pushed me to reflect on this condition that we all experience from time to time, the ending of something big and the beginning of a new life. To an extent, the trilogy follows the curve of this shocking resemblance between intimate experiences and global events.

The first part of the trilogy, UNMEMORY, is dedicated to the workings of human memory striving to piece together a coherent picture of the past out of disjointed and fragmented notions, acting like a person coming to what remained of their destroyed home. This was done based on real-life documentary material, not in a verbatim form, but in a way in which any memory actually works—as a collage, a series of echoes, and sensory associations without clear-cut divisions between personal and “social” reminiscences.

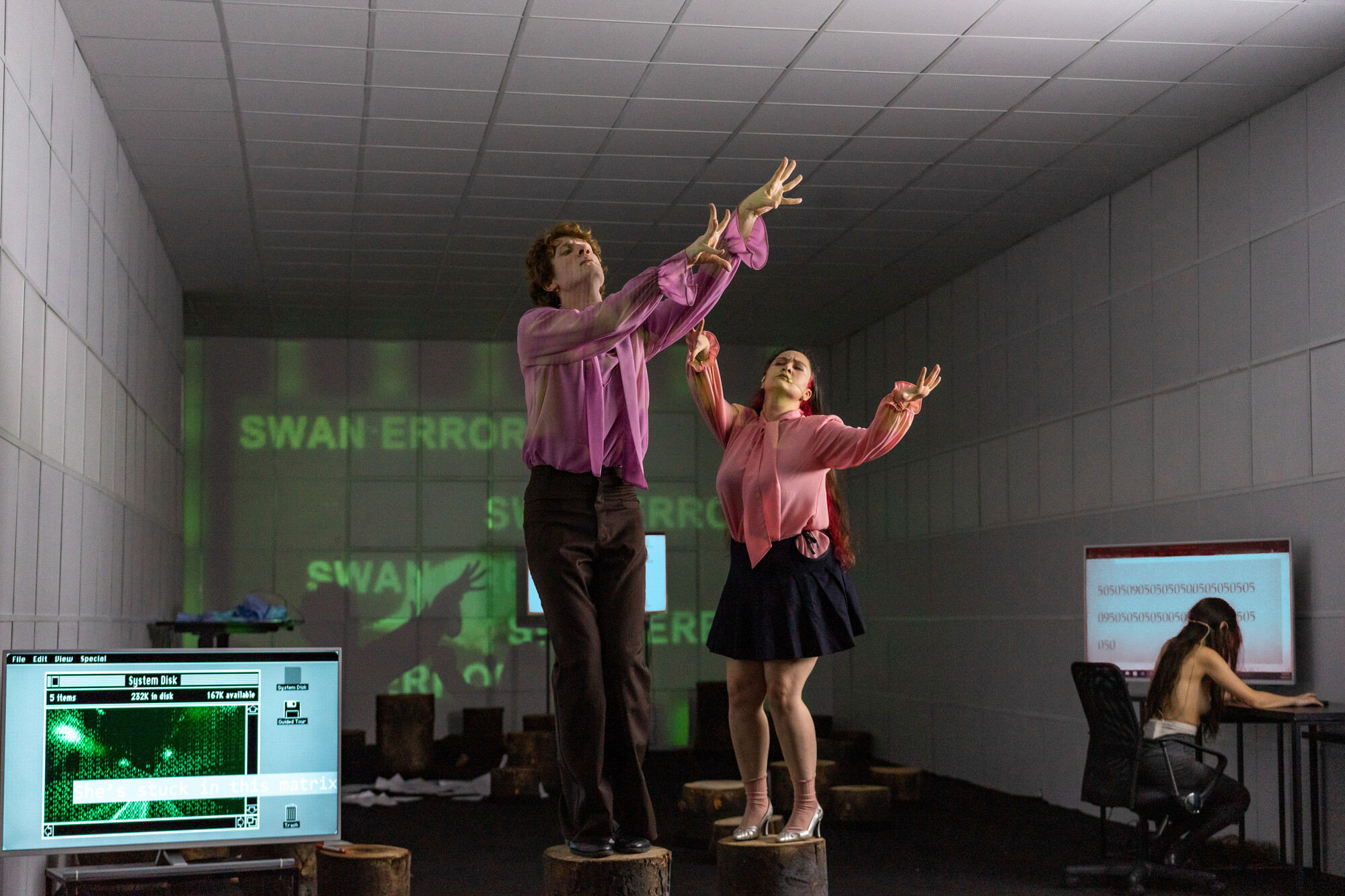

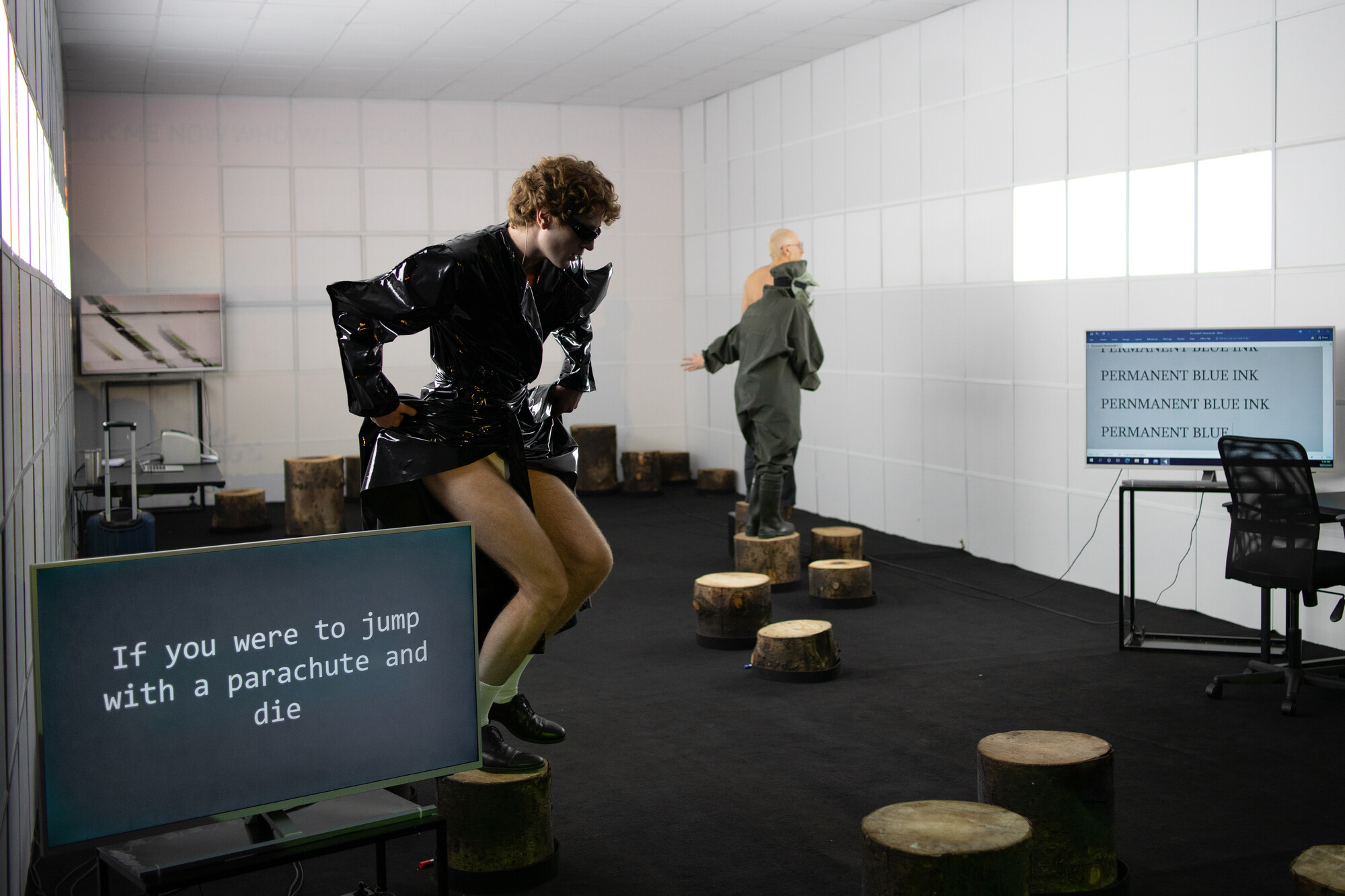

The second part of the trilogy, UNLOVE, was originally prototyped as an audio play at the time of the pandemic when all of us were trying to explore the available form of performativity and presence. However, I always meant it to be a real-life performance based on my personal documentary material surrounding the loss of love and the identity crisis that ensued. Just like in the case of UNMEMORY, its production coincided with a global crisis, which this time was the beginning of the full-scale aggression of Russia against Ukraine on 24 February 2022 that shook everyone in the team to the core. The onset of this new crisis was followed by some political moves undertaken by the Georgian government that required performative commentary. Thus, the performance naturally incorporated various political meanings, creating jarring rhymes between the unfolding humanitarian and political catastrophe on the one hand and the personal catastrophes of cut-off connections, abuse, and broken trust on the other.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here