Olga Sanchez Saltveit is the artistic director emerita for Milagro Theatre, the Pacific Northwest’s premier Latinx arts and culture organization, following her service as the company’s artistic director from 2003 until 2015. She is now also assistant professor of theatre at Middlebury College. Shayna Schlosberg is the equity leader at Oregon Public Broadcasting and moved to Portland, Oregon last summer after many years in Houston, Texas. These two leaders have spent their careers in service of the Latinx community. In this second part of their two-part conversation, they speak about the mentors who have shaped them, the trade-offs that come with a career in theatre, and their shared experiences working toward greater equity.

Understanding Theatre as Service, Part Two

Olga Sanchez Saltveit directing Tricks to Inherit by Fermín de Reygadas, translated and adapted by Olga Sanchez Saltveit, at University of Oregon. Directed by Olga Sanchez Saltveit. Scenic Design by Adam Whittredge. Costume Design by Jeanette de Jong. Lighting Design by Kat Matthews. Properties by Jerry Hooker.

Shayna Schlosberg: I'd love to hear more about your mentors.

Olga Sanchez Saltveit: José Carrillo came to mind first. I met him through our work at the Seattle Group Theatre. He was a theatremaker, a writer, an actor, a poet, and a clarinetist and flautist. He was always an inspiration. He was somebody who celebrated Latinidad and Chicanidad.

Then there was Rubén Sierra, who was with Teatro Nacionales de Aztlan (TENAZ) and started Seattle Group Theatre. His company, Teatro del Piojo, was founded in Seattle, Washington, inspired by Luis Valdez’s El Teatro Campesino. He formed his own company because he wanted to also be part of the movimiento and transform the experiences of Chicanos and Mexicanos through teatro. Seattle Group Theatre was one of the few multiethnic theatre companies in the country at the time. He wrote a play called When the Blues Chase Up a Rabbit and asked me if I would direct a reading in Seattle that he and his friends and collaborators in Seattle could see and give feedback. He was based in Portland by then. I directed two or three iterations of this reading, and we would always have a conversation afterwards. Then the play was selected by Milagro Theatre for a world premiere the following fall. In the spring, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. And he said, "I don't know what kind of shape I'm going to be in September, so I'm going to step away from that responsibility." He went to José González, executive artistic director of Milagro, and said, "Why don't you hire Olga? She's very familiar with the play, and she has directed two or three readings of it. I trust her with the work." So, I got hired.

Rubén’s play is about a young Chicano man who gets hit by a bus when he's in high school, and he is now paraplegic and needs constant care. He's in a wheelchair, and his dad’s got a terminal illness, and he knows he's dying. Now, this play was written before Rubén has his prognosis. So we're in the rehearsal process, and Rubén would come in, and he's losing weight. He's very thin. He would sit and talk with us about what it was like to know you're dying, which was the most generous act in service of the work.

The Latinx Theatre Commons inspired me to become an academic. It pointed to the need in the field to raise the visibility of Latine/x theatre through the archive.

In the play, the reason the kid was in the wheelchair was that he had presented an essay in front of his class and, because he was Chicano, the teacher doubted that he had written it. He was so frustrated that he just ran into the street and got hit by a school bus. So, it's a metaphor for the damage done in supposedly trustworthy places when our capacities are undermined based on our identities. Ultimately, what the father is asking him to do is like, "Get over it. You're in a wheelchair now. Come on, let's go. You got to be the man of the house.” It was a beautiful play.

Rubén was in the hospital near the end of his life. I went to visit him, and this was I think the last time I visited him. He drew me in closer because he was weak, and he said, "Now it's your turn. You have to carry it forward. You have to carry it on."

Shayna: Oh, wow.

Olga: I was handed this thing, whatever it was, to serve whatever this mission is moving forward. He was a mentor, not only in that he handed me this baton, but in his generosity putting the work ahead of himself, ahead of his own discomfort—and in his generosity in inviting me to come and direct his play at the one Hispanic identified theatre company in seven states. He gave me this really beautiful opportunity. Rubén sticks with me. He died too young.

A third mentor is Juliette Carrillo, who I met at the Latinx Theatre Commons Convening in Boston. She’s a super accomplished director and an inspiring artist with a tremendous heart. She has been a friend to help me navigate shifting gears into academia. The Latinx Theatre Commons inspired me to become an academic. It pointed to the need in the field to raise the visibility of Latine/x theatre through the archive. To paraphrase el maestro Jorge Huerta (another mentor!): if it’s not written about, it never existed. So much of our early work is undocumented, no pun intended. I had spent decades working in Latine theatre but found I couldn’t be a teacher in higher ed without the terminal degree, so I decided to get the PhD. But I really didn’t know what I was getting into. Juliette has talked me down off the ledge more than a few times, which has been great.

Shayna: Those are the important relationships.

You're going to do important work because you're already coming in with a desire to be in a space where you can make change.

Olga: I would love to hear about your mentors.

Shayna: I've struggled to find those. My first mentor is definitely my mom. Truly, there's no way I would've pursued the arts without her. She's someone I go to for advice. She has been a critical mentor to me, which I feel eternally lucky for.

Aside from her, it took me a long time to find mentors. There was virtually no one when I was focusing on performance that I developed that relationship with. When I moved into management, there was interest in people mentoring me. Frankly, the person that I developed a mentorship relationship with was an older white man, but there were limitations to our ability to connect on some things.

I expressed frustration about my struggles to find a mentor in the management space with a friend of mine, Pia Agrawal, who is now the executive director of Staten Island Arts. She's just a few years older than me, but she has been a great mentor to me. She connected me to a program called Women of Color in the Arts Leadership Through Mentorship that opened me up to a whole new community of women leaders and people who wanted to be mentors and who understood the challenge of finding mentors. The executive director of the program, Kaisha Johnson, became a mentor to me, and I ended up working for her. That has been a really special community as I found my way. I'm no longer in the theatre space.

Olga: What?

Shayna: Yeah, I know. It happens. Shocking. I miss working in the performing arts, and I know there is a lot of need for new management and new leadership in the performing arts. So likely I'll come back. But I've shifted full-time into racial equity work and diversity, equity, and inclusion work. That shift was influenced by my relationship with Women of Color in the Arts.

Shayna Schlosberg and Kaisha Johnson at the Women of Color in the Arts gathering in Houston organized by Shayna Schlosberg. Photo by Rebecca Herpin.

Olga: This thought crossed my mind, Shayna: where your heart is and where your mind is, where your intellect is and where your spirit is… It doesn't matter what space you enter, you're going to do useful work. You're going to do important work because you're already coming in with a desire to be in a space where you can make change.

Shayna: I feel like there's so much overlap between the racial equity work and theatre. Both are trying to connect us to each other’s humanity, to see the humanity in each other.

Olga: Life is also quite the journey. We don't know where your heart may lead you. I hope the doors open as you wish them to open in blessed ways.

Shayna: Thank you.

Olga: Is there anything that you gave up because of your dedication to the field?

Shayna: Stability and income. For me, it's always a trade-off. I'm either working with and for the people I want to work for, but I have to make financial sacrifices and personal sacrifices, or I work within a system and I get those needs met by working within a system that is not made for me.

Olga: I clearly remember when I applied for an MFA program, I was in the interview stage and they said, "So if you get your MFA, what do you want to do with this degree?" I said, "Well, I want to stay here in Seattle, and I want to be a better director in my community." They did not register that as valuable or viable. I mean, it certainly was not going to bring any glamour to this institution. I didn’t want to go anywhere but this Seattle-based university because I was committed to my community, and I saw my MFA go out the window. I knew at that moment that I was not going to get into this program. So I think I gave up my MFA. I think I may have given up children to be in the theatre, too, which has to do with just burning the candle at all ends—

Shayna: That's so real.

The absence of practitioners like us is really felt in cities like Houston and Seattle, outside of the big cultural hubs.

Olga: And just my body going like, "Nope, nope. You don't have space in your life to do this. It's not going to happen. Not in this body."

Shayna: There's a cost to everything, isn't there?

Olga: Yeah, there is. I don't regret it. Other things come up. Other things show up.

Shayna: What do you want people to remember you for?

Olga: Service. My service to the work, that I really approached it with all my heart, at Seattle Teatro Latino and all the new plays that we worked on. Then, when I became an artistic director: how was I supporting a generation coming up? And then with the Latinx Theatre Commons: how can I support this larger thing that a bunch of us are doing? Because I believe in it. Now, as an educator: how do I walk into spaces with humility but also understand that I also have a responsibility for what comes out of my mouth, who I champion, who I bring into the classroom, what values I uphold, and how I treat my students?

Shayna: I have no doubt that that is what you are already known for.

Olga: Oh, thank you. That’s so kind.

Shayna: I think that's a noble decision, your choice to stay in Seattle, to focus on the community in Seattle, even if it cost you your MFA. Until I moved out here to the Pacific Northwest for family reasons, I was super committed to Houston, Texas. That was something that a lot of people didn't understand, and it was an internal struggle for me, too, sometimes. Like, "Oh, what am I giving up here by staying in this community? The absence of practitioners like us is really felt in cities like Houston and Seattle, outside of the big cultural hubs.

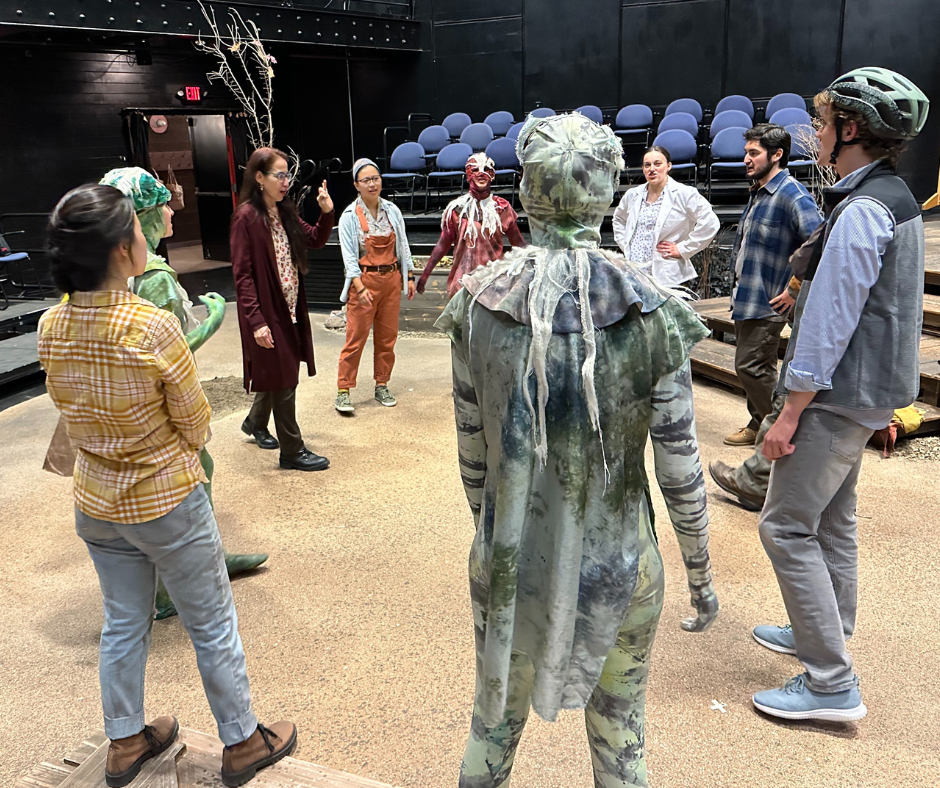

Olga Sanchez Saltveit and members of the cast and team of Somewhere by Marisela Treviño Orta at Middlebury College. Directed by Olga Sanchez Saltveit. Scenic Design by Mark Evancho. Costume Design by Summer Lee Jack. Lighting and Projections Design by Courtney Smith. Sound Design by Madison Middleton. Photo by Stephen Mease.

Olga: Well, I appreciate that. I don't know that I was being noble as much as I was being honest. I knew why I wanted to get an MFA: it was to serve better in my community. I knew an MFA would make me a stronger director. As it turns out, actually working at a Latino identified theatre company for twelve years also helps. So when I took the gig, I was like, "I'll be a better director at the end of this," and I am. I'm also a better grant writer. A door closes, a window opens. Or a window closes, a door opens.

Shayna: If you're aligned with your values, too, that's when things start moving.

Olga: How do you balance working for change while preserving your energies?

Shayna: I journal every morning, which has been a life-changing practice for me. I prioritize friendships and relationships in the same way that I prioritize my work. Thankfully this is a larger shift that's happening. People in my generation are asking that we rethink our relationship to work.

Olga: Absolutely. For the longest time I burned the candle at both ends. It took being with the artEquity Women of Color in Leadership circle and retreats to go like, "Oh no, I need to make sure that I nourish my own self, my body, my mind if I'm going to be of service, if I'm going to be effective.” I’m getting more sleep now. Getting the PhD nearly killed me. I never slept. It was terrible. I also do yoga every morning, a little bit of Tai chi. I'm trying to invest a little bit more time in that. I have to figure out what my battles are and where I can be effective. Pacing myself in the change, but keeping the courage to keep pushing, in small conversations and larger ones.

Shayna: I'm in the exact same place. Pacing yourself, picking your battles. It's hard to do, when people are hungry for change, when people are hurting. But change takes time.

Olga: It also takes community. It takes building alliances and changing hearts. In some cases, some people are ready to come and work, and some people are not. How do we align so that we're working in concert to create change rather than in opposition? It happens more effectively if it's in the heart.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here