Matthew: Building on the notion of using time-tested jokes, you’ve now done two adaptations of Molière. When approaching an adaptation, how do you update the humor of the piece?

Herbert: I come up with the theme first. Where am I putting this old dusty play and in what new context? In Manifest Destinitis, for example, it was in early California. In Bad Hombres, it was narcoland. Once I decide on the theme, that dictates the style of comedy. Manifest Destinitis is set in early California, so it should use early vaudeville makeup, floor lights, and Western melodrama. Bad Hombres/Good Wives was written in a campy TV novela style. There are narcos, nuns, and a foul-mouthed female mariachi by the name Lucha Grande. The performance is filled with banda songs, which feature roguish cowboys and tales of lovelorn narcos.

In those cases, I can’t throw a contemporary joke in because it wouldn’t be true. It’s the easiest way to get a laugh, throwing something in that’s a total non sequitur, but it pulls you out. I’ll still do it once in a while. It’s partly how I comment on the play: “Don’t take this so seriously folks.” Even I don’t take it seriously. I like to remind audiences that they are a big part of the experience.

We hear about whites appropriating Latino culture, well I appropriate white culture and make it relevant to us.

Matthew: How do you decide what to keep from the old comedy?

Herbert: What I kept from Molière are those universal, very human moments. When I read these old texts, I can see there are jokes, and they probably killed in the seventeenth-century, but they’re not funny anymore. So I take the essence of the joke and I’ll heighten it. I’ll make it nastier or bilingualize it. Something to make it new.

I have that other weapon, too. I use a lot of Spanish. Culture Clash’s comedy is bicultural and inclusive—we really do use humor that appeals to both a Latinx audience and a mainstream audience. Sometimes we include jokes that are only funny to a white audience, jokes that are geared to the subscriber. That’s why I throw in the classics, like Molière. To tantalize them. But then I switch it on them, I put it in Spanish.

It’s appropriation. We hear about whites appropriating Latino culture, well I appropriate white culture and make it relevant to us.

Matthew: What’s happening in the interplay between Spanish and English that works comically?

Herbert: It’s a rhythm thing. There’s just the rhythm—the sound of certain Spanish words are funny already. I’ve always said that you can mention the word “carne asada” and it will surely get a laugh! I’m bilingual, so it’s really natural for me to write like that. And I’ll get complaints: “There’s too much Spanish.” I know if there’s too much Spanish people won’t get it, and I don’t want people not to get it, but I think there are certain jokes that are just for bilingual people, and that’s okay. There are millions of us. And that is America’s future audience, too.

I’m not apologetic about it. It’s important to get people’s ears used to it. It takes me a while to understand Shakespeare, and then, little by little, my ear gets accustomed to it.

Matthew: In that case, a bilingual comedy is performing an important social role. It’s getting an audience used to hearing Spanish on stage.

Herbert: San Diego Rep is fifteen minutes from a Spanish-speaking country. Fifteen minutes! Why wouldn’t there be Spanish in my play?

I got two reactions to Bad Hombres: “There was too much Spanish, I was left out,” or, “Thank you for putting Spanish in the piece. I was on the edge of my seat and it made me concentrate more.”

Matthew: I’m curious how the rehearsal process helped shape Bad Hombres.

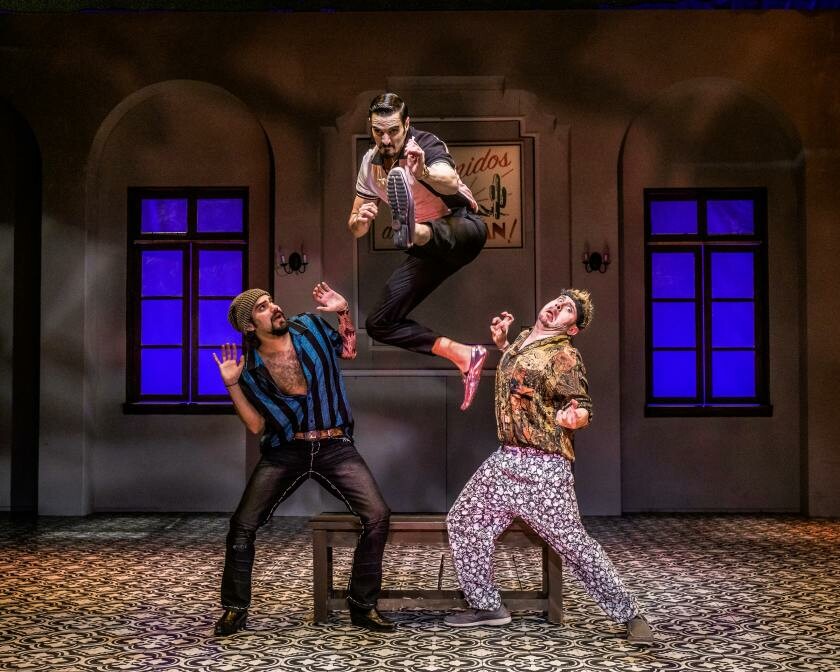

Herbert: I try to get as close as I can to comedy on the page, but I knew we would find a lot of physical comedy once we staged it. It was screaming for it. It goes back to style—that heightened style requires physical comedy. We used people’s fortes, whatever they are. For example, we found out that Jose Balistrieri—Mario in Bad Hombres—is super athletic, and we used that throughout the whole play. Dancing, fighting, jumping through windows. It was so easy for him, and people loved it.

Whatever people can do, I’ll use. You can sing? I’ll give you a song. John Padilla—Don Ernesto in Bad Hombres—sings well, so I gave him another song, which ends the first act. I didn’t see that coming until I heard him sing during a reading.

Comedy is a real collaborative process. I don’t think my text is sacred, that it can’t be changed. If someone has a better idea, we’ll do it. Culture Clash has always been that way when working with directors. We’ll suggest something, but if their ideas are better, we’ll go with it, always. Don’t be stubborn.

I don’t think my text is sacred, that it can’t be changed. If someone has a better idea, we’ll do it.

Matthew: What about in performance? What do you learn in previews that helps you hone the jokes?

Herbert: Previews are all about finding the rhythm, the musicality of the play. You know there is a laugh there, but it’s not happening. So you go back and say, “Okay, what are we doing that’s not provoking that laugh, or what are we not doing that’s not provoking that laugh?”

As performances go on, I’ll checkmark a page and go back to the original script, and sure enough there’s a word in there blocking the joke, or someone didn’t do a double take or a pause. It’s all these little things. And then after two or three previews, you start hearing the rhythm. Every show should sound the same. Text, laughter. Text, Laughter. Like a symphony. Some nights are bigger and more boisterous, of course. In my plays, it depends on how many Latinos I have in the audience.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

It thrills me to know that this kind of comedic theatre is being created! This is exactly what I long for. I can't even find the script anywhere online though...what does a girl on the other side of the country have to do to access this exciting new work?