The Legacy of Luis Valdez and El Teatro Campesino

The First Fifty Years / El Legado de Luis Valdez y El Teatro Campesino: Los Primeros Cincuenta Años

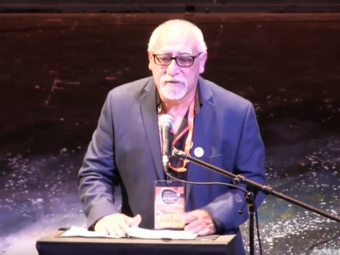

The following remarks are taken from a speech Jorge Huerta gave at San Jose State University on September 24, 2015 to honor Luis Valdez and the fiftieth anniversary of the Teatro Campesino.

The Birth of El Teatro Campesino

When I think about a theatrical legacy I usually imagine that the person or theatre group that has left a legacy is no longer with us. Indeed, my Webster’s defines legacy as “anything handed down from the past, as from an ancestor.” But what if that “ancestor” still exists and is sitting in the room? Thankfully, Luis Valdez, his better half, Lupe, and the Teatro are very much alive, but they are now “classics” because they have withstood the test of time. Everything they have produced is still as relevant, entertaining, educational, and necessary as it was fifty years ago. They say that art is essential in a civilized society and the art that has been created by Luis and the Teatro ensemble proves that statement. This is about the role of the artist in a society in crisis.

The Teatro and its founder have gone through several incarnations since 1965. In its first fifteen years the troupe evolved from a farm worker’s theatre to a community-based/student group, to an international touring company producing and publishing films, recordings and anthologies, and finally, to a professional producing organization. I believe that all of the theatrical activity of Chicanas and Chicanos—indeed, Latinas and Latinos—from community and student teatros to professional theatre companies and individual theatre artists and filmmakers, owe their existence, directly or indirectly to Luis Valdez and the Teatro Campesino.

I begin this discussion with the earliest examples of the Teatro Campesino’s aesthetic and political legacies because these continue to hold sway with many community-based and student teatros working today. But Chicana and Chicano theatre artists have come a long way since the early days of the Chicano Theatre Movement. This “professionalization” of Chicano theatre can be attributed to individual efforts, certainly, but one cannot ignore the impact of Zoot Suit in this evolutionary process.

Demographics and economics notwithstanding, Zoot Suit opened the doors to the “mainstream.” And although that play has been attributed to Luis Valdez, it demonstrates the work of the collective as well. That magnificent play with music combines elements of the acto, corrido, carpa, and mito with Brechtian and Living Newspaper techniques to dramatize a Chicano family in crisis. The members of the Teatro Campesino of that period can take pride in knowing that their collective exercises inspired and invigorated the playwright/director to create the most important play written and/or directed by a Chicano to date, a formidable legacy.

One can never really return to the past because conditions change. The young people who make up today’s Teatro Campesino are perhaps the original troupe’s most vital living legacy. Kinan Valdez has taken over the role of Artistic Director and is continuing the legacy as a brilliant director, actor, playwright, and facilitator/motivator (like his dad), along with the younger generation of Campesino members. These descendants of the original founders were literally born into the Teatro Campesino. Their training was hands-on from the time they could walk, benefitting from the years of workshops, performances, and tours that their parents would take them on, diaper bags in hand.

I am treating the Teatro Campesino as a collective entity because the Teatro and its founder are sometimes interchangeable. Perhaps the Teatro Campesino could have emerged under the direction and tutelage of another person but that would have been a completely different group. However collective the work of the Teatro may have been in the group’s first fifteen years, I know that Valdez guided the group with his own world view, an aesthetic, spiritual, and political vision that drove his creative spirit. Learning is a two-way process and neither the director nor the Teatro members could have continued their artistic development without a dedicated and constantly evolving ensemble.

The Acto and the Rasquachismo Aesthetic

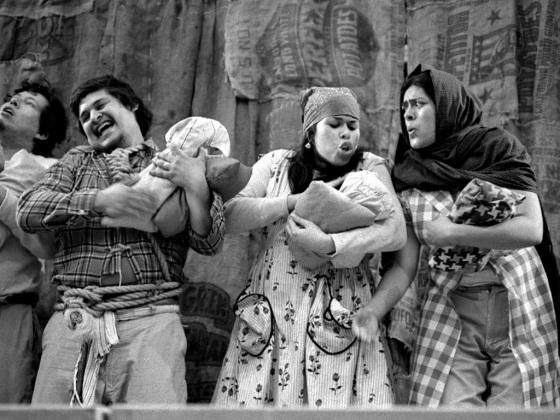

The theatrical form that dominated the Teatro’s presentations from 1965 to 1970 was the acto, so named by Valdez for expediency’s sake. An acto is a short, usually comical sketch, often created through improvisation, that is designed to be performed anywhere. The actos were ideally suited for the Teatro’s initial efforts to get farm workers to join the Union Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta were founding. In the typical acto, the heroes and villains are clearly defined and a solution is either hinted at or plainly stated: “Join the Union,” “Boycott grapes,” etc. The acto form is one of the most important aesthetic and political legacies from the early Teatro Campesino, and although the aesthetic legacy is sometimes difficult to separate from the political, in the realm of aesthetics the Teatro Campesino developed what has sometimes been called the “Rasquachi aesthetic.” As Diana Taylor states in her landmark study, The Archive and the Repertoire, rasquachismo represents “the aesthetics of the underdog.”

The actos were ideally suited for the Teatro’s initial efforts to get farm workers to join the Union Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta were founding.

“Rasquachismo” is a truly Chicano term, a condition of the working class understood by the people who have had to negotiate the uncertainties of life “en el norte” (north of Mexico). As an aesthetic, the earliest Teatro Campesino actos were truly rasquachi. Because the group had no money, they had to be prepared to perform anywhere, usually outdoors, and design elements came together by chance. The actos were simple but not simplistic, inventive by necessity. Therefore signs around the necks of the actors mark the characters clearly and masks further delineate the villain (pig face mask) from the heroes (no masks). Costumes are found and the exaggerated props are put together in somebody’s kitchen. The Rasquachi aesthetic cannot be “designed,” it just happens.

During the first fifteen years of the Teatro Campesino’s trajectory the group developed other performance genres, all reflecting the rasquachi aesthetic in one way or another. Those forms were the mito (myth), the corrido, and the carpa. The mito was more of a personal statement for Valdez in his efforts to rescue the Chicanos’ indigenous heritage. The Teatro’s invocations of indigenous thought and culture can be seen in many of the plays written by Chicanas and Chicanos which employ either actual indigenous characters, or symbols on stage such as flutes and drums, recalling the ancient Mesoamerican cultures that preceded the Spaniards. Another genre that can be termed unique to the Teatro Campesino is the corrido, first explored as a performance technique in 1971.

The Teatro Campesino’s initial socio-political legacy can be clearly seen in the various themes their actos, songs, and other performance techniques exposed in presentations across the country and even abroad, bringing the plight of the Mechicano to a wide variety of audiences. The Teatro became a voice for the voiceless, giving Chicano audiences in particular, a sense of belonging in a society that had ignored and suppressed them for generations. Sadly, every one of the issues the Teatro exposed is still relevant. Those issues, in the order of their appearance in the collectively created actos, are: farm labor, cultural denial, internal colonization, lack of equitable educational opportunities, inner conflicts in the Chicano Movement, police brutality, an unjust judicial system, and the disproportionate number of Chicanos who were fighting and dying in Vietnam. Although strides have been made in some of these areas, every one of these issues, and more, still plague Mechicanos.

The Teatro became a voice for the voiceless, giving Chicano audiences in particular, a sense of belonging in a society that had ignored and suppressed them for generations.

Since the Teatro located to San Juan Bautista, California, in 1971, their centro became a mecca for theatre artists, scholars, and students from around the globe who went to observe the work, or to participate in the ongoing workshops. Some people stayed and became members of the ensemble, others returned to their own teatros, renewed, invigorated, and perhaps inspired to continue in theatre or to take another professional path. From all accounts, no one left a residency in San Juan Bautista unchanged.

Along with the members of today’s Teatro Campesino, perhaps the troupe’s most obvious legacy is found in the other Chicano theatre troupes and individual theatre artists that this company inspired. One of the earliest teatros that owed its genesis and its creative expressions to the Teatro Campesino was the Teatro Urbano, founded right in this city (San Jose, California) in 1968 by Luis Valdez’s younger brother, Daniel. This urban counterpart to the farm worker’s theatre became the second (documented) Chicano theatre troupe. It seems that everywhere the Teatro performed they inspired others to create their own teatros, widening the field. In 1970 the Teatro began to organize and host Chicano theatre festivals in an effort to assess the field and to enhance the development of these mainly student groups just beginning to explore their roles as cultural workers.

By 1973 the number of teatros had swelled to at least sixty-four active groups. Within ten years of its creation the Teatro Campesino had almost single-handedly fostered a national theatre movement. And although few of those teatros are still operating, the Teatro had a very real reach into the hearts and minds of the groups, their individual members, and the widening circle of audiences.

The publication of the Teatro Campesino’s first actos in 1971 gave new teatros excellent and effective actos to produce, adapt, and emulate. The anthology was the first of its kind; until that book appeared, no other collection of actos (or plays) had been published. Teatros throughout the country began to (re)produce those quintessential actos, changing locations, names, or other signifiers to best suit their audiences. Farm worker actos were transposed to urban workers’ strikes; Los vendidos was adapted to suit a particular community’s stereotypes. The educational issues exposed in No saco nada de la escuela (I Don’t Get Anything Out of School) led to many variations on the theme. The messages were clear: the Chicana/o had grievances and they had better be addressed. Many people, especially students who witnessed those and other actos became active participants in demonstrations, boycotts, sit-ins, and other activities dedicated to improving the conditions of their people.

The Influence of El Teatro Campesino

Only a handful of teatros from the early 1970s are still operating; other companies have been founded in their wake. Although we can trace the influences of the Teatro and Valdez from coast-to-coast, I want to highlight two theatre groups that can trace their beginnings to the direct influences of the Teatro Campesino: Teatro Vision, in San Jose, and the Latino Theater Company in Los Angeles.

Teatro Vision evolved from Teatro Urbano (1968) to Teatro de la Gente (1970), (founded by Manuel Martinez and Adrian Vargas), to Teatro Vision, founded by Elisa Marina Alvarado, in 1986. Elisa had been a prominent member of Teatro de la Gente and an active participant in the national coalition of Teatros, El Teatro Nacional de Aztlán (The National Theater of Aztlán) that the Teatro Campesino and others launched in 1971. Elisa founded Teatro Vision along with other Chicanas, eager to make the women’s voices heard and continues to lead the Teatro, running the company much as the early teatros did, as a collective.

José Luis Valenzuela, like Elisa Alvarado, had also been a member of Teatro de la Gente. As readers of Café Onda know, Valenzuela is the founding Artistic Director of the Latino Theater Company, and the head of the Los Angeles Theatre Center (LATC). In an old bank in downtown Los Angeles, the LATC boasts five performance spaces—the largest and most comprehensive teatro in the country. In 1986 Valenzuela and his wife, actress and playwright Evelina Fernandez, moved to Los Angeles, where they formed a company of professional actors eager to perform plays that spoke to their community, which became the Latino Theater Company. All of the members had an impressive resume of acting experience in Hollywood as well as in Chicano theatres. Like many other Latina/o actors working in Hollywood, some had been in Zoot Suit either in Los Angeles or New York (or both), as well as in the film of that play. They each brought knowledge of professional theatre and film to the company and were crucial to its success, acting in almost all of the plays the company produced.

In the fall of 2014 the Los Angeles Theater Center and the Latino Theater Company, under the leadership and vision of Valenzuela and in concert with the Latina/o Theatre Commons (LTC) organized and hosted a major event, the Encuentro 2014, a month-long festival of Latina/o theatre companies from across the country and Puerto Rico. I dare to say that everybody in that Encuentro was there because of the tenacity of the pioneers, hosting festivals and workshops in order to grow aesthetically as well as politically. This was the first festival of its kind, the result of years of fund-raising and collaborating with the Latina/o Theatre Commons Steering Committee. From flatbed trucks and tin can lighting to this incredible facility; from mimeographed fliers to web sites y todo, we’ve come a long way, baby!

Many of the artists and scholars involved in the Encuentro 2014 returned to their respective companies, universities, and communities with a renewed sense of purpose. We continue to learn from one another in the tradition of the earliest festivals. The times have changed, the technology has changed, but the people remain people and this Encuentro and the recent LTC Carnaval of New Latina/o Work in Chicago, are living proof that the future of Latina/o theatre is in very good hands.

The Issues Remain Urgent

The Teatro Campesino lives today not only as a world-renowned theatre company, but also in the thousands of people whose lives were changed by one of their performances or a performance of one of their actos or Valdez’s plays produced by another teatro, a university, or mainstream theatre company. And do not discount the millions who have been moved and inspired by the films. The Teatro lives in the continuing work of so many people who passed through the troupe’s cultural centers. It lives in the people who participated in workshops conducted by the teatro members either at home or on tour. The teatro continues to inspire, giving the Chicana and Chicano a sense of place and a pride in who they are. Remember that I titled this essay “The Legacy of Luis Valdez and El Teatro Campesino: The First Fifty Years.” Here’s to the next fifty years as the legacy continues.

Las siguientes observaciones fueron tomadas del discurso de Jorge Huerta en San Jose State University del 24 de septiembre de 2015 en honor a Luis Valdez y al cincuentenario del Teatro Campesino.

El Nacimiento del Teatro Campesino:

Cuando pienso en un legado teatral usualmente me imagino que esa persona, o grupo de teatro, ya no está con nosotros. En realidad, mi diccionario Webster define legado como “algo que viene del pasado, como si de un ancestro” (nota del editor: en español se define como “lo que se deja o transmite a cualquier sucesor). Pero qué tal si ese “ancestro” aún existe y está sentado aquí. Por suerte, Luis Valdez, su media naranja Lupe, y el Teatro, están muy vivos, pero ahora ellos ya son “clásicos” porque han resistido la prueba del tiempo. Todo lo que han producido aún sigue relevante, entretenido, educativo, y necesario al igual como lo fue hace cincuenta años. Dicen que el arte es esencial en una sociedad civilizada, y el arte que ha sido creado por Luis y los miembros del Teatro revalida ese dicho. Lo siguiente trata con el papel que desempeña el artista en una sociedad en crisis.

El Teatro y su fundador han pasado por varias encarnaciones desde 1965. En sus primeros quince años, el grupo evolucionó de ser un teatro de campesinos a un grupo estudiantil y comunitario, a luego una compañía en gira internacional produciendo y distribuyendo películas, grabaciones y antologías, y a finalmente, una organización profesional de producción. Yo creo que toda la actividad teatral de Chicanas y Chicanos—en verdad, latinas y latinos—desde teatros comunitarios y estudiantiles a compañías de teatro profesionales, teatristas independientes y cineastas, le deben su existencia, directamente o indirectamente a Luís Valdez y al Teatro Campesino.

Comienzo este discurso con los primeros ejemplos de la estética y legados políticos del Teatro Campesino porque continúan influenciando muchos teatros estudiantiles y comunitarios que trabajan hoy en día. Los teatristas Chicanas y Chicanos han llegado muy lejos desde esos primeros días del Chicano Theatre Movement. Esta “profesionalización” del teatro Chicano se puede atribuir a los esfuerzos de individuos, ciertamente, pero uno no puede ignorar el impacto de Zoot Suit en este proceso evolucionario.

A pesar de las realidades demográficas y económicas, Zoot Suit le abrió las puertas a la “corriente prevaleciente.” Y aunque esa obra haya sido atribuida a Luis Valdez, también demuestra el resultado del trabajo colectivo. Esa magnífica obra con música combina los elementos del acto, corrido, carpa y mito con las técnicas Brechtianas y del Living Newspaper para dramatizar una familia chicana en crisis. Los miembros del Teatro Campesino de aquella época pueden tomar orgullo en saber que sus ejercicios colectivos inspiraron y envigorizaron al dramaturgo/director a crear la obra más importante escrita y/o dirigida por un chicano hasta la fecha; un legado formidable.

Uno nunca puede verdaderamente regresar al pasado porque las condiciones cambian. Los jóvenes que componen el Teatro Campesino de hoy en día son, tal vez, el legado vital y en vida de la compañía original. Kinan Valdez ha tomado el puesto de Director Artístico y continúa el legado como brillante director, actor, dramaturgo, y facilitador/motivador (como su padre), junto a la generación más joven de miembros del Teatro Campesino. Estos descendientes de los fundadores originales literalmente nacieron en el Teatro Campesino. Su entrenamiento fue en la práctica y empezaron desde que podían caminar, beneficiándose de años de talleres, presentaciones, y giras a las que los llevaron sus padres, pañaleras en manos.

Estoy considerando al Teatro Campesino como una entidad colectiva porque el Teatro y su fundador son, a veces, intercambiables. Tal vez el Teatro Campesino pudiera haber surgido bajo la dirección y tutela de otra persona pero hubiera sido un grupo totalmente diferente. No importa que tan colectivo haya sido el trabajo del Teatro en los primeros quince años, yo sé que Valdez guió a este grupo con su propia perspectiva del mundo, con una visión estética, espiritual, y política que guiaba su espíritu creativo. El aprendizaje es un proceso de doble-vía y ni el director ni los miembros de Teatro hubieran podido continuar su desarrollo artístico sin un grupo dedicado y en constante evolución.

La Estética del Acto y el Rascuachismo

La forma teatral que dominó las presentaciones del Teatro de 1965 a 1970 fue el acto, nombrado así por Valdez por razones de conveniencia. Un acto es una obra corta, usualmente cómica, a menudo creada a través de la improvisación, que es diseñada para presentarse en cualquier lugar. Los actos eran perfectamente adecuados para cumplir la misión inicial del Teatro en atraer a campesinos a unirse al sindicato que César Chávez y Dolores Huerta estaban creando. En un acto típico, los héroes y los villanos están claramente definidos y la solución es insinuada o anunciada de manera sencilla: “Únanse al Sindicato,” “Boicoteen las uvas,” etc. El acto como forma teatral es uno de los legados de estética y política más importante del joven Teatro Campesino y, aunque el legado de estética y política es a veces difícil de separar, el Teatro Campesino, en cuestión de estéticas, a desarrollado lo que a veces se le llama “estética Rascuachi”. Como dijo Diana Taylor en su reconocido estudio, The Archive and The Repertoire, el rascuachismo representa “la estética del desvalido.”

“Rascuachismo” es un término realmente Chicano, una condición de la clase trabajadora entendida por la gente que ha tenido que negociar con las incertidumbres de la vida “en el norte”, o al norte de México. En su estética, los primeros actos del Teatro Campesino eran verdaderamente rascuachi. Como el grupo no tenía dinero, tenían que estar preparados para presentarse en cualquier lugar, usualmente al aire libre, y los elementos de diseño se reunían casi por suerte. Los actos eran simples pero no simplistas, inventivos por necesidad. Por lo tanto, carteles colgados de los cuellos de los actores indican a los personajes y máscaras apartan al villano (máscara de cerdo) de los héroes (sin máscara). Los vestuarios son prestados y la utilería exagerada construida en alguna cocina de algún conocido. La estética rascuachi no se puede “diseñar,” simplemente ocurre.

Durante los primeros quince años de su trayectoria, el Teatro Campesino desarrolló otros géneros teatrales, todos reflejando la estética rascuachi de una manera u otra. Estas formas eran el mito, el corrido, y la carpa. El mito fue, más bien, una afirmación personal de Valdez en su esfuerzo por reclamar las raíces indígenas de los Chicanos. Las invocaciones de ideas y cultura indígenas del Teatro se pueden ver en muchas de las obras escritas por Chicanas y Chicanos que incluyen personajes auténticamente indígenas o elementos escénicos como flautas y tambores, resucitando de esta forma a la cultura Mesoamericana que precedió a los Españoles. Otro género que se puede atribuir como único del Teatro Campesino es el corrido, inicialmente explorado como una técnica de presentación en 1971.

El legado socio-político inicial del Teatro Campesino se puede ver claramente en la variada motivación de sus actos, canciones, y otras técnicas de teatro presentadas en funciones por todo el país y en el exterior, presentando a una gran variedad de audiencias la difícil existencia del “Mechicano”. El Teatro se convirtió en la voz de los que no la tenían, y en particular le dio a su público Chicano el sentido de pertenecer a una sociedad que los había ignorado y suprimido por generaciones. Tristemente, cada uno de los temas que el Teatro dio a relucir siguen relevantes. Esos temas, en el orden como surgieron en los actos creados colectivamente son: el trabajo de campo, el rechazo cultural, la colonización interiorizada, la desigualdad en oportunidades educativas, conflictos internos en el Movimiento Chicano, brutalidad policial, un sistema judicial injusto, y un número desproporcionado de Chicanos que pelearon y murieron en Vietnam. Aunque se han logrado avances en algunas de estas áreas, cada uno de estos problemas, y otros más, continúan plagando a los Mechicanos.

Cuando el Teatro se situó en San Juan Bautista, California en el 1971, se convirtió en una meca para artistas, académicos, y estudiantes de todas partes del mundo que iban a observar el trabajo o a participar en los talleres. Algunas personas se quedaban y se convertían en miembros del grupo, otros regresaban a sus propios teatros, renovados y tal vez inspirados a continuar haciendo teatro o cambiarse de profesión. De cualquier forma, nadie terminaba su residencia en San Juan Bautista sin algún cambio.

Incluyendo a los actuales miembros del Teatro Campesino, quizás el legado más obvio del grupo se encuentra en las otras compañías de teatro Chicanas y en los artistas independientes que esta compañía ha inspirado. Uno de los primeros teatros que le debe su génesis y su expresión creativa al Teatro Campesino fue el Teatro Urbano, fundado aquí en esta misma ciudad (San José, California) en 1968 por Daniel, el hermano menor de Luis Valdez. Este equivalente urbano al teatro de campesinos fue el segundo grupo (documentado) de teatro Chicano. Parece ser que en todos los lugares donde se presentó el Teatro, inspiró a otros a crear sus propios teatros, ampliando el panorama. En 1970 el Teatro comenzó a organizar y hospedar festivales de teatro Chicano con la intención de evaluar el campo teatral y ayudar en la formación y desarrollo de estos grupos, principalmente estudiantiles, que apenas comenzaban a explorar su función como trabajadores culturales.

En 1973 el número total de teatros creció a, por lo menos, sesenta y cuatro grupos activos. A los diez años de su creación, el Teatro Campesino había fomentado, casi sin ayuda, un movimiento nacional de teatro. Y aunque muy pocos de esos teatros siguen funcionando, el Teatro tuvo un verdadero alcance en las mentes y corazones de los grupos, sus miembros, y el creciente círculo de audiencias.

La publicación en 1971 de los primeros actos del Teatro Campesino dio a nuevos teatros unas excelentes y efectivas obras para producir, adaptar, y emular. La antología fue la primera de su tipo; hasta que ese libro apareció, ninguna otra colección de actos (u obras) había sido publicada. Los teatros por todo el país comenzaron a (re)producir estos actos por excelencia, cambiando lugares, nombres, o cualquier otros elementos para adaptarse mejor a sus públicos. Los actos de campesinos fueron trasladados a las huelgas de los trabajadores urbanos; Los vendidos fue adaptado para servir los estereotipos de una comunidad en particular. Las cuestiones educativas expuestas en No saco nada de la escuela engendraron muchas variaciones sobre el tema. Los mensajes eran claros: Los Chicana/os tenían quejas y más valía que fueran abordadas. Mucha gente, especialmente los estudiantes que presenciaron estos y otros actos se convirtieron en participantes activos en las demostraciones, los boicoteos, sentadas, y otras actividades dedicadas a mejorar de las circunstancias de su gente.

La Influencia del Teatro Campesino

Son pocos los teatros fundados a principios de los 70s que aún siguen funcionando; otras compañías han surgido de sus huellas. Aunque podemos encontrar las influencias del Teatro y de Valdez de costa a costa, quiero resaltar a dos grupos teatrales que sí pueden rastrear sus principios a las influencias directas del Teatro Campesino: Teatro Vision, en San José, y el Latino Theater Company en Los Angeles.

Teatro Visión evolucionó del Teatro Urbano (1968) al Teatro de la Gente (1970), (fundado por Manuel Martínez y Adrián Vargas) al Teatro Visión, fundado por Elisa Marina Alvarado en 1986. Elisa fue miembro prominente del Teatro de la Gente y una participante activa en la coalición nacional de Teatros: El Teatro Nacional de Aztlán que el Teatro Campesino y otros lanzaron en 1971. Elisa fundó Teatro Visión junto a otras Chicanas entusiasmadas por hacer escuchar las voces femeninas y aún continúa dirigiendo su teatro, guiando a la compañía como lo hacían muchos de los primeros teatros, como un colectivo.

José Luis Valenzuela, igual como Elisa Alvarado, también fue miembro del Teatro de La Gente. Como los que leen Café Onda sabrán, Valenzuela es el Director Artístico y fundador del Latino Theater Company, y director de Los Angeles Theater Center (LATC). Situado en un viejo banco en el centro de Los Ángeles, el LATC alardea cinco espacios teatrales--el teatro más grande y exhaustivo del país. En 1986, Valenzuela y su esposa, la actriz y dramaturga Evelina Fernández, se mudaron a Los Angeles, donde formaron una compañía de actores profesionales entusiasmados por presentar obras que hablaban de su comunidad. Esta se convirtió en el Latino Theater Company. Todos los miembros tenían un currículo impresionante lleno de experiencia como actores tanto en Hollywood como en teatros Chicanos y, al igual que muchos otros actores latina/os en Hollywood, unos habían actuado en Zoot Suit en Los Angeles o en Nueva York (o en ambos), así como también en la película de esa obra. Cada uno trajo conocimiento de cine y teatro profesional a la compañía y fueron cruciales en su éxito, actuando por ende en casi todas las obras que la compañía produjo.

En otoño del 2014, Los Angeles Theater Center y el Latino Theater Company, bajo el liderazgo y visión de Valenzuela y trabajando en concierto con el Latina/o Theater Commons (LTC) organizaron y hospedaron un evento significativo, el Encuentro 2014, un festival de compañías Latinas de teatro de todas partes del país y Puerto Rico. Me atrevo a decir que todos los participantes en el Encuentro estaban ahí gracias a la tenacidad de los pioneros, que produjeron festivales y daban talleres para crecer estética- y política-mente. Este fue el primer festival de su tipo, un resultado de años de recaudación de fondos y colaboraciones con el Comité Directivo del Latina/o Theater Commons. De camionetas pick up y luces de latas a este increíble complejo teatral; de folletos mimeografiados a páginas de web y todo, hemos llegado muy lejos!

Muchos de los artistas y académicos que participaron en Encuentro 2014 regresaron a sus respectivas compañías, universidades, y comunidades con un nuevo sentido de propósito. Nosotros continuamos aprendiendo el uno del otro en la tradición de los primeros festivales. Los tiempos han cambiado, la tecnología ha cambiado, pero la gente permanece gente y este Encuentro y el reciente LTC Carnaval of New Latina/o Work en Chicago, son pruebas vivientes de que el futuro del teatro latino está en buenas manos.

Los Problemas Siguen Siendo Urgentes

El Teatro Campesino vive hoy no solo como una compañía de teatro reconocida mundialmente sino también en las vidas de miles de personas cuyas vidas fueron cambiadas por una de sus presentaciones o una presentación de uno de sus actos o por las obras de Valdez producidas por otros teatros, universidades, o compañías de teatro prevalecientes. Y no descuenten los millones que han sido conmovidos e inspirados por las películas. El Teatro vive en el trabajo continuo de tantas personas que han pasado por el centro cultural del grupo. Vive en la gente que participa en los talleres conducidos por miembros del Teatro ya sea en su ciudad o en gira. El Teatro continúa inspirando, dándole a la Chicana y al Chicano un sentido de pertenencia y orgullo en su identidad. Recuerden que titulé este ensayo “El Legado de Luis Valdez y el Teatro Campesino: Los Primeros Cincuenta Años.” Brindemos por los próximos cincuenta y el legado continuara!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Jorge, this is a wonderful tribute to not only Luis Valdez and his family but to everybody involved con El Teatro Campesino. Luis Valdez and his group of artistas and performers show the reality of how Farm Workers are treated in this country it is quite shameful.

Thank you, profe, for the fantastic essay--what a great way to celebrate the legacy of El Teatro Campesino.

This write up is just timely for my new Chicano Theatre Class I will be teaching during the spring semester... so thank you, Tío, Jorge!

Gracias for sharing this important part of our history as Theater artists.

Thank you! We've updated the caption.

Fantastic article. Thank you very much!

Thank you for writing this and sharing your work with all of us! This should be required reading for all.

Jorge,

From a historical-scholarly perspective this is a beautiful and important essay. It's also a magnificent tribute to Luis, Lupe, Kinan and the rest of the teatristas that have made Teatro Campesino's legacy unparalleled in the American Theatre. Thank you!!