Writing Our Own Rules, to the End

After over a decade and twenty-five new play productions, the playwright-run Workhaus Collective calls it a conclusion.

In the thaw of my first winter in Minnesota in 2005, a dozen transplanted playwrights came to share bourbon and popcorn over in my small apartment. Brought to the Twin Cities from around the country, we had all found ourselves in a terrific community of playwrights, thanks to The Playwrights’ Center and the Jerome Foundation. We had a writing community, but we were all flying elsewhere for our world premieres. A lot of us felt isolated in this pattern, without a solid artistic home. There was not a new play producing community in this community rich with playwrights. Dominic Orlando and I had both produced our own work in New York City, and we thought: why not do that here, only pool together this time? We invited our colleagues to discuss new models of making our work happen: with so many great playwrights in such close proximity, how many of us would be interested in producing each others plays? Make this place a real artistic home, for however long we’re here? DIY. Playwrights behind the wheel. Steer this thing ourselves.

Out of this meeting, a group of eight or so playwrights became Workhaus Collective, a playwrights’ run theatre collective that is now in our tenth full season, producing our 25th play, the beautifully ambitious Lasso of Truth by Carson Kreitzer. Over the years, Workhaus Collective members have been Alan Berks, Jeannine Coulombe, Carson Kreitzer, Christina Ham, Cory Hinkle, Dominic Orlando, Deborah Stein, Victoria Stewart, Joe Waechter, Stanton Wood, and myself. We’ve never had a single producing director, a single artistic director, and we’ve never had a stated aesthetic except to support the playwrights’ vision for a given play. We have, for ten years, been a loose band of Twin Cities-based playwrights working collectively, messily, diligently, to produce each other’s most risk-taking work. We have produced an average of three member plays a year, for ten years.

In our last two years as a Collective, we expanded to be one of the companies in residence at the Southern Theater, as part of ArtShare program. We continued our long-standing relationship as company in residence at The Playwrights’ Center, and (after all this time) became our own 501c3. We have operated without debt, and we have tried to contain any drama to the stage: our Collective has decided each season in collective agreement, organically based on our own availability, personal artistic goals, and collectively accepted “sweat equity.” Things in many ways have been going great. And our members are doing great in our careers: five of our members are now finding success on the West Coast, as teachers and television writers. Local members are having a wildly successful year, with four productions in the Twin Cities this season of Christina Ham’s plays, three of Alan Berks plays, and continued success of Jeannine Coulombe’s TYA plays at Stages Theatre Company. Looking at our individual and group track record, Workhaus Collective has done us collective good.

Since we began our journey in 2006 there are far more examples of playwright-driven theatre companies across the nation, such as the Welders in Washington, DC, Orbiter 3 in Philadelphia, and Boston Public Works, to name a few, with each company seeming to learn from each other, and form their own rules. Some companies are forming with a built-in termination date: an agreement to run for a few years together, then pass the baton. Workhaus Collective never had much of a formal definition. In many ways, we agreed each season to still exist, based on our own needs, our passion for what we could contribute to theatre as a whole, and our capacity. As I wrote in HowlRound two years ago, we have always made our decisions organically, together.

Workhaus Collective may just be the only theatre company in the US to be run exclusively by playwrights. Not only are the playwrights of the collective the artistic directors of the company, we have also been the administrators at every level, from production to fundraising, from marketing to ticket sales. We balanced our own careers with the needs of the Collective company, with no one leader. Amazingly, this loose model has worked for a decade.

Workhaus has meant that my work was able to be realized on my terms.—Christina Ham, Workhaus Collective member

Ten years in, we faced a major turnover of members. It was not that the membership wanted to see Workhaus Collective say goodbye—it was that much of the membership needed to say goodbye to Workhaus Collective. In many ways, the Collective is a victim of our own success. As we were looking at a major turnover in Collective members, we considered the options. It’s hard to let a good thing go: wouldn’t it be great to try to pass it on? But we didn’t feel right imposing our culture on people, insisting that they do things our way. We came together to support each other’s work, and the Workhaus Collective has always operated, as Carson Kreitzer puts it, “on the principle of Radical Generosity.” Radical Generosity means we sacrifice our time for what a member playwright chooses to do, without question. As Carson says, “we don’t choose plays; we choose playwrights, and those playwrights support each other, and each others’ visions. When it is your turn, the Collective says, ‘What play do you most want to see produced?’ And then we do it.” This system requires very high levels of passion, commitment, and trust. “We feel that these are bonds and alliances new groups will be better off forging for themselves,” says Kreitzer, acknowledging what our Collective knows to be true—that the collective worked by writing our rules together, finding our passion together. It was never about simply seeking a home for our work: all of us could get productions elsewhere. It has been about taking risks: “Workhaus allowed me to risk in a world where failure is not seen as an acceptable career option, yet for the growth of an artist it is imperative,” says Jeannine Coulombe. It was about connection: “As a playwright, you often want to hide in the back row listening to your play,” says Victoria Stewart, “But producing 800 Words: The Transmigration of Philip K. Dick, I had to truly own my play and walk into a bookstore and say, "Hey, I wrote a play about Philip K. Dick, I think you'd like it." Because I had to make these one to one relationships, I think I had a significantly more engaged audience, one that was just as invested in the play as I was.” It was about taking power: as Christina Ham puts it, “Workhaus has meant that my work was able to be realized on my terms.”

“Workhaus demonstrates the viability and the power of playwright-centric productions, and how valuable it is for playwrights to control a budget, and control the artistic choices, and the financial artistic trade-offs that any kind of production process entails,” says Stanton Wood.

It has been a place for all of us to realize the kind of collaborations we desire, from traditional-but-better writer-director relationships, to writer-actor collaborations, to hybrid forms of writing and devising.

We have all used the Collective to accomplish different goals, unified around the ideas of playwrights’ connecting to the audience directly, taking risks, and being in charge of them. In my last three productions with the Collective, I have used Workhaus as a means to exercise my most genre-divergent ideas and test my riskiest plays with vigorous workshop productions. Deborah Stein has done a similar thing, test-driving her now internationally produced Chimera in workshops with Workhaus. It’s been a safe place for us to directly share with our audience. It’s also a place, for writers like Victoria Stewart and Carson Kreitzer to realize the vision of their plays that had not been realized elsewhere, proving that polished productions with exciting design do not require big budgets. It’s been a place for writers like Alan Berks and Dominic Orlando to realize their works under their own direction. It has been a place for all of us to realize the kind of collaborations we desire, from traditional-but-better writer-director relationships, to writer-actor collaborations, to hybrid forms of writing and devising. We have made this possible through the commitment we have made to be to each other what we desire from each other. This model is made possible by having a strong group, rather than a strong individual. And our groups’ needs and lives had changed.

And so, as it began organically, it is ending organically. As we gathered over bourbon and popcorn in each others’ houses, we determined that to keep the integrity of what Workhaus has always been for, it was time for it to conclude.

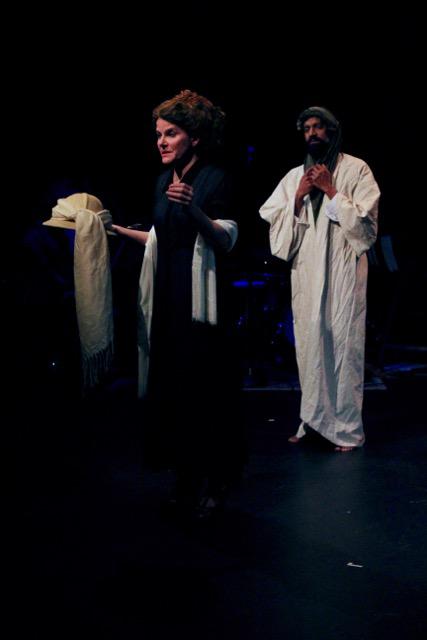

We are so pleased to close with the sure-to-be-beautiful production Lasso of Truth by Carson Kreitzer—Carson, who was at the very first group brainstorm towards the Collective at my apartment back in 2005. We are so pleased that as we close our Collective together, we are working with many of the artists who have supported us since the beginning, working in three different ways: on a world premiere at the Southern Theater (Alan Berks’s Feast of Wolves), on a first draft of a production built to tour (Trista Baldwin’s Eye of the Lamb), and on a play that’s already proved successful on stage (Kreitzer’s Lasso of Truth), now realized for the first time through the playwright’s own vision of the production. It’s an especially strong season to end with, making it bittersweet to let go.

However, we will not fully let go until we document our work; we will be publishing an anthology of our decade of new plays together, and we will be reflecting as we have begun to do with this essay here. Workhaus Collective has been an unusual model that’s been unusually successful. Our final project together will be to document our process and to share with a larger audience what we have created.

It’s been a good ride, together, one that has helped all of us grow as writers and theatre artists. It’s a ride that we hope to embolden others to take. If playwrights continue to directly connect to their audiences, to take the risks that help them grow, and to take the power of production into their own hands, this theatre world of ours will grow stronger, healthier and more exhilarating for all.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this article! It is helpful and inspiring as my playwrights collective sets new goals this year!

the just the idea of a playwrights collective sounds oxymoronic,radical,revolutionary; ten years of sharing a common dream in a cooperative, respectful spirit, without regimentation or loss of individuality is to be admired and congratulated and emulated. Thank You, Trista Baldwin.