A Lover's Guide to American Playwrights

María Irene Fornés

Every morning and many times a day, as we walk downstairs from the bedroom and office that were cobbled together out of the attic of our Seattle house, my wife and I are greeted by a picture of María Irene Fornés, sitting beneath a marble angel in the Saint-Gaudens' Baptistery of the Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square in New York's Greenwich Village. The angel faces to the left, eyes downcast or closed, holding a sign. But the angel's arm, bare from the shoulder, where her wing appears out of pleated, flowing robes, seems to be cradling Fornés herself. The angel's chin fairly rests on the crown of the playwright's head. Fornés faces the opposite way, also looking down, mouth slightly open (hint of a smile), also apparently at peace.

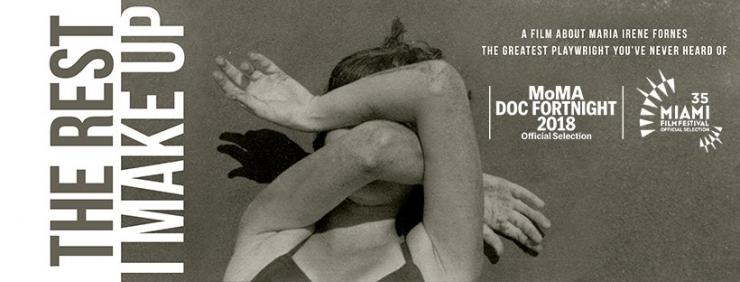

The cross-hatched lines on the subject's face echo the fine, etched folds in the angel's robes. Irene wears a button-down shirt with a rattan circle-weave pattern the color of old rose and a crinkled scarf, a dark sapphire blue. Words float above her shoulder in the direction of the angel's lidded gaze: "ME IN/GO YE/NATION/NAME" from an inscription that begins, "ALL POWER IS GIVEN UNTO ME IN HEAVEN AND IN EARTH—GO YE THEREFORE AND TEACH ALL NATIONS BAPTIZING THEM IN THE NAME OF..." and so on. This doubly angelic portrait, which we got for donating to the final edit of Michelle Memran's profoundly moving documentary about Fornés, The Rest I Make Up, hangs above the final steps between our loft room and the daily world. It blesses our comings and goings.

All to say: María Irene Fornés is our Art Angel.

María Irene Fornés: the most important playwright your friends and family never heard of and the most influential playwriting teacher in fifty years.

I've often wondered how artists, overlooked in their lifetimes, grow in recognition and influence later, how they, posthumously, become canonized. Irene Fornés, still with us at almost eighty-eight years old and in the late stages of Alzheimer's, may be undergoing just this metamorphosis, from ignored to eternal. She remains unknown by most audiences and, despite nine Obie Awards, including one for lifetime achievement, uncelebrated by the culture at large.

At the same time, she has been written about extensively by devoted critics, scholars, and artists, most consistently through the intellectual/editorial graces of Marc Robinson, Caridad Svich, Maria M. Delgado, Bonnie Maranca, Scott T. Cummings, and, most recently, Anne García-Romero. There has been a resurgence of her work in production, including at the Festival Irene in Los Angeles in 2016; part of Hero Theatre's work, led by Elisa Bocanegra, all the festival proceeds went to Irene's care. Fornés has been embraced by a couple generations of playwrights, notably students from her legendary Hispanic Playwrights-in-Residence Lab at INTAR off-Broadway and the Padua Hills Playwrights' Workshop. My wife, Karen Hartman, was one of Irene's students at Yale, and I rediscover, year after year, play after play, how deeply the teacher's example has burrowed into the student's vision. Major writers—Tony Kushner, Paula Vogel, Mac Wellman, and her contemporary Sam Shepard among them—cite her as a principal influence and inspiration. María Irene Fornés: the most important playwright your friends and family never heard of and the most influential playwriting teacher in fifty years.

Now the The Fornés Institute has launched from within the Latinx Theatre Commons (LTC) to preserve and archive her legacy as a teacher, mentor, and artist. The LTC has joined forces with Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts to host the 2018 LTC María Irene Fornés Institute Symposium this weekend, followed by an academic Colloquium at New York University. And then there's Memran's documentary, fifteen years in the making, a stirring portrait of an artist as a young then old woman. The Rest I Make Up also offers an unparalleled glimpse into the progress and impact of dementia. In one wrenching episode, Memran travels to a newly opened Havana with Fornés, who basks in a life-changing reunion with her beloved Cuban family; only days later, back in New York, the playwright seems to have forgotten the trip. As much as anything, the film is a love story between an almost accidental filmmaker and her subject. Fornés, who approaches her characters as a passionate suitor approaches the beloved, is now, as if by some supernatural transference, the object of fascination, transfixing her author/documentarian without end. How fitting for an artist who, though invisible to much of the world of arts and letters, is beloved by the populace of a village called the American theatre. This love has manifested in a fierce, protective guardianship of Fornés by Memran, dramaturg/activist Morgan Jenness, playwright Migdalia Cruz, and Dr. Gwendolyn Alker, as well as a daily host of theatre artists—mostly women—who make their way to the care facility where Irene lives, to talk with her, sing and play music for her, pore with her over old photos, hold her hand, brush her hair.

George Bernard Shaw wrote intricate, detailed stage directions so that, in the early days of play publishing, his plays—as books—could be read. María Irene Fornés writes precise, specific set descriptions, so that we might see her plays. Take the opening of Mud (1983):

The set is a wooden room which sits on an earth promontory. The promontory is five feet high and covers the same periphery as the room. The wood has the color and texture of bone that has dried in the sun. It is ashen and cold. The earth in the promontory is red and soft and so is the earth around it. There is no greenery. Behind the promontory there is a vast blue sky. On the back wall of the room there is an oversized fireplace which is the same color and texture as the walls and floor. [...] Inside the fireplace there are two cardboard boxes. One is full and tied with a string, and the other is empty. On the mantelpiece there are, from right to left: a brown paper bag with a pamphlet in it, a plate with broken bread, a pitcher with milk, a textbook, a notebook and pencil, a dish with string beans, a folded newspaper and a box with pills. Between the fireplace and the door to the left there are an ax and a rifle....

We see color and texture—earth red, sky blue, the cold ash of sundried bone. We notice scale: from the "vast" and "oversized" to things as small as a bean or the string tied around a cardboard box. The bleached bone-scape reminds us of O'Keefe; the mantelpiece, maybe, of Vermeer. The ax and rifle foretell a violent end. And there, among all the things we spy through the Fornés' painterly, sculptor's eye, are things we cannot see—a pamphlet, pills—that which resides invisibly within the seen.

This landscape is infused, much the way words of poems are infused—with emotion, energy, with meaning, apparent and strange and contradictory. It is both imagistic and palpably real at the same time, the way Fornés's plays are imagistic and real—distilled, infused things, occupied by all-too-real people in situations that merge ecstasy and hurt. Can you hear this mixture in the stilted, grief-inflected joy of the fifteen-year-old Marion from Abingdon Square, about to marry a man thirty-five years her elder? She speaks to her fiancé's son, a child the same age she is:

Soon I will, officially, be your mother, and I say this in earnest, I hope I can make myself worthy of both you and your father. He brought solace to me when I knew nothing but grief. I experienced joy only when he was with me. His kindness brought me back to life. I am grateful to him and I love him. I would have died had he not come to save me. I love him more than my own life and I owe it to him. And I love you because you are his son, and you have a sweetness the same as his. I hope I can make myself worthy of the love you have both bestowed upon me and I hope to be worthy of the honor of being asked to be one of this household which is blessed—with a noble and pure spirit. I'm honored to be invited to share this with you and I hope that I succeed in being as noble of spirit as those who invite me to share it with them. I know I sound very formal, and that my words seem studied. But there is no other way I can express what I feel. In this house light comes through the windows as if it delights in entering. I feel the same. I delight in entering here and when I'm not here I feel sad.

The early 1900s Greenwich Village setting recalls Edith Wharton and Henry James, as well as The Heiress, the famous stage and screen adaptation of James's Washington Square. The characters, too, might have stepped out of one of their novels. But there the resemblance stops.

There is a quality to Fornés's plays that is hard to find in prose dramatic works that come before them: a double-ness, in which the drama is both a picture of the real and an art object at the same time. It's an experience we have in visual art all the time, when we are called at once by the paint and the subject, the surface of the work and the thing depicted. It is harder to find in twentieth-century plays before the sixties, when writers like Edward Albee, Adrienne Kennedy, and, maybe especially, Fornés, begin to take on style with the intensity that their predecessors took on story or subject.

For Fornés, a play, like a poem, doesn't start with an idea, a subject; it begins with an invitation of spirit, a request for imagined others to speak.

When did American theatre writers begin to think of themselves as artists? When did they become artists? Didn't the term "writer" used to be enough, as it described this thing done by mostly men at mostly typewriters as a way of dramatizing the news and issues of their times and the contradictory humanity of the people around them? At some point "writer" must have seemed insufficient, as though it didn't fully apply.

María Irene Fornés is, I believe, the mother of this shift—from the largely literary and somewhat journalistic idea of the dramatist to the example of writer-as-artist: She of formal intensity and free-range imagination, driven less by the logic of ego than by the emotional affinities of the subconscious. In this sense, Fornés has been for fifty years our preeminent playwright-artist.

As an artist of imaginative/subconscious affinity, she teaches her audience, as she famously teaches her playwriting students, to move toward what moves us. In class she does this by beginning with yoga and movement, by triggering writers with pictures and prompts, guiding them to put voice to what they see, to invite this or that character to speak, to welcome a new soul into the room, the scene. This passage from her Letters from Cuba (2000) sounds like a Fornés manifesto. Joseph speaks:

I've been writing poetry. And I've been saying words in my head to see if word spirits would come, like move in, like to join other words that were there. If they would do that then, to see if they would come in to form a poem. I think that's how poems get written. I think that's how difficult things get done. We can't really do them. We can't do difficult things. We can do easy things. But the difficult ones come to us by themselves. It's just that to learn to listen to them is difficult. We just have to learn to listen and to let them come in easy as if the words would come out by themselves because they want to make a poem. As if words had desires, and they want to join other words to express something...of beauty or longing or despair.

We listen to the desires in our words, and let them "come out by themselves," come together by themselves to make the difficult thing that would express something, that would be a poem. For Fornés, a play, like a poem, doesn't start with an idea, a subject; it begins with an invitation of spirit, a request for imagined others to speak.

Irene has become our art angel, too, by standing outside of the marketplace of the American theatre. She has never aimed to please, never been or, far as I can tell, tried to be other than who she is. Like a secular Saint Joan, she has listened—always and only—to her inner voices. As actress Deirdre O'Connell puts it in Conducting a Life: Reflections on the Theatre of Maria Irene Fornés, edited by Delgado and Svich, "...She only and absolutely does what she wants to do and only and absolutely makes the art she wants to see. She is completely true." In that same volume, another actress, Madeleine Potter, Abingdon Square's original Marion, describes how, at a moment of paralysis in tech rehearsals, Irene spoke directly to her imagination and "soul." "I will never forget it because she taught me two great things for my work and for my life: that the only road for the artist is to forge further into the imagination, and that imagination is the only refuge from fear."

Aristotle insisted that, "What a thing can be, it must be..." I read this as a mandate from the old Greek taxonomist and anatomist: the highest form of artistry is that which gives form to essence, makes the most of its own intrinsic gifts. Fornés's lessons speak to the souls of artists because she lives by this code. Her plays are utterly themselves. They satisfy in final articulation their potential for being—what they can be. They become what they must be. Genius, I believe, manifests in those who occupy and fulfill themselves most completely. By conducting her life toward the fullest imaginable flowering of her own unique Irene-ness, Fornés has lived a life of incomparable genius.

I have to admit, confess really, that my first encounters with Irene were a bust. I was her nominal dramaturg on the production of Chekhov's Uncle Vanya she directed for CSC Rep in New York in 1987, starring Austin Pendleton, Alma Cuervo, and Michael O'Keefe. I say nominal because, though I'd held that position at the theatre for more than a year and though I'd been promoted to associate artistic director on the basis of something or other, I really had no idea what a dramaturg was supposed to do, especially when, as almost always happened, the director had no use for me or interest in finding one.

And Irene had neither use nor interest. The thought of kicking conceptual ideas around with her or showing up with an armload of research or, god forbid, discussing textual revisions—well, let's just say there was nothing in her manner or behavior that inspired me to give it a try. I didn't even understand what she was doing. Was she even a director, I wondered in my young director-man's arrogance? They were doing Chekhov, for fuck's sake, and she didn't talk about subtext or Russia or even what the characters were to each other, what made them tick, what they wanted. Mostly she moved the actor's hands and heads, sculpting them in space, creating a physical score that had none of the improvisatory naturalness I associated with the interpretation of Chekhov.

Irene, I had to learn, was making a work of art. She was funneling Chekhov's precise, personal vision through her own equally precise subjectivity. This has been true of every one of the many productions of hers I've seen through the years. They could only have been made by her. Of how many productions can you say that: only this playwright or this director could have made so personal and idiosyncratic a work of art? But Irene's Chekhov didn't feel like American naturalism, didn't psychologize like Lee Strasberg's Method acting or underscore its ethics like an Arthur Miller play. It didn't explain itself.

American theatrical culture has not yet learned to embrace that which does not explain itself. As Bonnie Maranca writes in The Theater of Maria Irene Fornes, edited by Marc Robinson,

What Fornés has done in her approach to realism over the years[...]is to lift the burden of psychology, declamation, moralism, and sentimentality from the concept of character. She has freed characters from explaining themselves in a way that attempts to suggest interpretations of their actions, and put them in scenes that create a single emotive moment, as precise in what it does not articulate as in what does get said.

I was young and stupid. I didn't know how to see something that didn't remind me of something I already knew. I would learn—and every time I read or see a play by Fornés, I have to learn it again—that art is a strange business, that familiarity is the enemy, that the most important artists give us new eyes to see. Sometimes we need angels to remind us, to cradle us, to rest their chins on the crowns of our heads and bless our inadequacies. In time, maybe, we learn to stay still and listen.

Angels do sit on peoples' laps

when they need to advise you,

They sit quietly,

so don't start getting up

and doing something you think is important and is not.

—María Irene Fornés, Letters from Cuba

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Describing how Fornés wrote her plays, Garland Wright once told me that she held her pen up to the paper and the plays wrote themselves. The first passage quoted here from "Letters from Cuba" brings Garland's observation to mind.

Thank you so much for this Todd, you bring her back to us all this way! I remember her making us (students) move and feeding us lines we had to incorporate some way, and she was always asking the strangest questions - almost like a fortune teller - no nails on any heads - sideways, sideways, the way you approach a wild animal or a bird, so it doesn't run away. When I've gone to visit her, there are all these women in the day-room so jealous of her visitors, and I've tried to explain to them how important she is to all of us, but it's not possible. They have families who don't visit. She has disciples. . .

"In this house light comes through the windows as if it delights in entering." Thanks, Irene. Thanks, Todd.

This is a beautiful clear-eyed and personal look/feeling at Irene's work. We all stand on her shoulders. Thanks for writing this, Todd.

Thank you for this. Really tremendous.

This is a great piece. I would like to share a humble homage to María Irene from 2005 when she received the Miami International Theater Festival Lifetime Achievement Award: http://ctda.library.miami.e...

Wonderful essay, Todd. You capture something, not only about Irene, but about all artists and art. Thanks for sharing this.

This should be required reading for any and all!

Todd's tribute to Irene is beautiful, astounding, and (a term deemed positive that I often suspect) fitting. Irene is clearly sitting on Todd's lap as Todd thinks and writes about her. Oh so wisely (not obedient, not bewitched, but one human being receiving gifts from a timeless other) Todd does not get up. Reading his evocation of Irene's magnificence and impact, we experience Irene's spirit infuse Todd's and through Todd in this luminous instance infuse us all.