Crossing Over

Arts, Military, and Passing to the Other Side

This week, HowlRound is partnering with New England Foundation for the Arts in advance of our convening—Art in the Service of Understanding: Bridging Artists, Military, Veterans, and Civilian Communities March 10—12. This convening was inspired by artists who created five new performance works with their collaborators in the military, healthcare and presenter communities, funded by NEFA’s National Dance and Theater Projects. This series asks: How can artists most effectively build relationships of trust as they engage in this work? What do military service members and veterans need to know to encourage them to work with artists? What do artists need to know about trauma in working with military and veterans’ communities?

NEFA has a long and rich relationship with artist Liz Lerman, who will bring an excerpt of Healing Wars to the convening with two of her collaborators. New Englanders vividly and passionately remember her work at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire Navy Yard.—Jane Preston, NEFA.

When my father was close to the end of his life, he told us that he wanted to be buried in his uniform. He meant his tenth Mountain Division uniform, the one he wore while fighting in Northern Italy in the final months of World War II. The same uniform he was wearing while on board a ship taking him from the European theatre to the fighting in the Pacific; they heard that a massive bomb had been dropped on cities in Japan, the war was over, and they could go home. The same uniform that was always stuffed in the closet, the attic, or the basement of houses we lived in as I grew up.

The family was shocked about this chosen attire for the grave: the only time we could get him to talk about the war was if we sat with him while he watched the TV show Combat!, or caught on to what he was really talking about with his occasional chiding of us about what sissies we were when it came to dirt, food, and privacy. He was better known for his labor organizing, his civil rights leadership, and his democratic party politics than he was for being a military man.

I have some new perspectives on my father’s desire to greet death as a soldier, to live in the beyond with that identity. It’s not that he wants to fight until the end of time; I think he wants to love until the end of time.

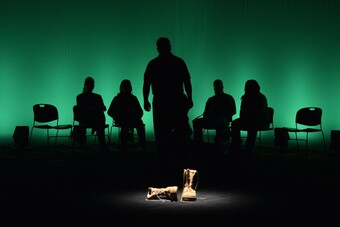

After spending the past five years developing, performing, and touring Healing Wars, a dance-theatre piece in which characters travel between the Civil War and our current conflicts, I have some new perspectives on my father’s desire to greet death as a soldier, to live in the beyond with that identity. It’s not that he wants to fight until the end of time; I think he wants to love until the end of time. And not romantic love, but a deep abiding love for comrades in time of risk, for buddies in times of boredom, and for shared purpose when so much of life is diffuse.

My father volunteered to serve his country in World War II, but he refused to carry a gun. So they trained him to be a medic instead. I don’t know very much of what happened to him overseas—I wasn’t there. But this I do know now: despite a life well-lived with civil justice at its core, deep inside he still missed the risk, the purpose, and the love that are such an essential part of the military service. I only fully came to understand this by speaking with many veterans as we made Healing Wars. By including Paul Hurley, an Iraq-era veteran, in the cast and hearing his story over and over each time we performed, I was finally able to glimpse the totality of the military experience—the intense drama of moral certitude and the potential damage done when that goes awry. Which it will, because it is war.

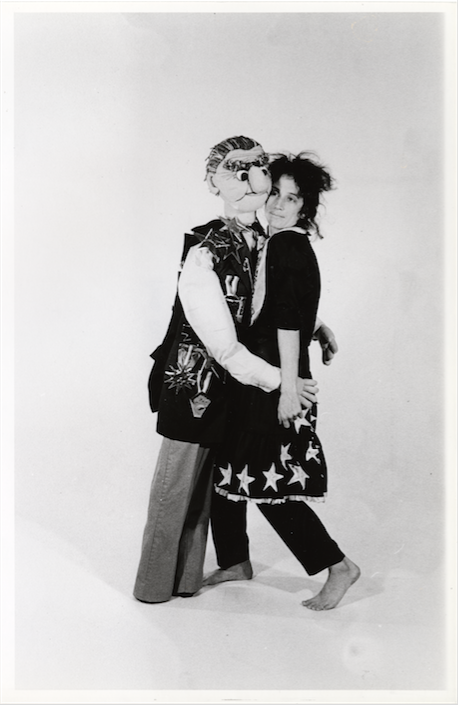

Other Military Matters, 1983. Photo courtesy of Liz Lerman.

War by the Numbers and Closing a Bridge

Besides being part of the protests against the Vietnam War in the ’70s, my own relationship to the military began more intensely in 1983 with my piece Nine Short Dances about the Defense Budget and other Military Matters. This “docudance” (the name I gave a series of works about politics and contemporary events constructed over several decades) was made out of my extreme desire to understand things I couldn’t fathom any other way. In this case I was struggling to understand the numbers, the astronomical amount of money we spent on the war machine that keeps America safe. I learned a lot by researching and interviewing; I then chose several different approaches to the problem of conveying such large data. Although shocked and thoroughly annoyed by the revolving doors between the Pentagon and other parts of the federal government, I was a pretty cheerful guide for audiences who were mostly as clueless as I was. Had we really built tanks with 18-foot blind spots in front of them? (Yes) And were there nuclear warheads aimed at almost every part of the globe? (Yes) Were we in a deep arms race? (Yes) And could any of us actually understand what one billion dollars bought? (Probably not; although we sang a song to help—filled with analogies that might convey scale, including the final line of each chorus: one-third of a trident submarine).

Because of this history, I was surprised to receive a call in 1993 from Jane Hirshberg in New Hampshire, who was the head of the education program at the Music Hall in Portsmouth at the time. The Hall was interested in doing a project with neighboring Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, spurred in part by the Yard’s appearance on the federal list of military installations to be closed. Jane wondered whether we would like to do a residency aiming to collect, save, and reclaim the nearly 200 years and ten generations of stories that would likely get lost if the Yard shut down.

Despite my personal reservations, I went for a visit. And my life thereafter was altered. Many things caused me to explore the problems put before us: how does a contemporary dance company work in a shipyard? What forms could the stories take? How could we be accepted when we had three generations of gay men in the company and the Yard was known for its homophobia? But one particular meeting, along with many small incidents in that week, made us all want to get to work.

Gathered in a midsized room, set up with chairs in rows, I was asked to talk about my interest and then to listen to what everyone had to say. I am not now sure why I went first. But I surprised myself in that I began to talk about my mother. She was one of the first women in a PhD program in Mathematics at UC Berkeley when World War II started. She was recruited to work on a secret project for Howard Hughes. I knew nothing of this until, when we were living in Milwaukee, she glanced at the newspaper one day and realized that her “ship” was coming in. This is a bizarre twist, but in honor of the Saint Lawrence Seaway opening to the port of Milwaukee, the city decided to have a mock invasion—and my mother’s boat was to be part of it. My family went down to the Lake Michigan beach and watched. Because her project had been secret, my mother had only worked on parts of it and didn’t really know what the whole thing—whatever it was—looked like. So in great anticipation we watched as a large boat pulled up near the shore, opened its lower hatch, and let the water rush in. And then, miraculously, many tiny boats floated out, small enough to reach the beach because they were so nimble.

I was telling this story to a bunch of military personnel, civilian engineers who designed submarines, and interested community people who loved, or hated the Yard, but were happy to be allowed onto the mostly secret installation. I really can’t explain it, but some connection was made. What followed was an amazing evening of stories including this one: some of the engineers in the room had designed the Thresher, a nuclear submarine that in 1963 was lost in a test-run; all 129 people on board were lost. This accident, which predates the space shuttle Challenger explosion by twenty-three years and the Kursk submarine disaster by thirty-seven years, lived in the memory of everyone working at the Yard. Also in the room were family members of people who had died on the Thresher. For some of them in the room, it was the first time they were all together in one place. In that encounter I could feel and see the imaginative possibilities of what art might do for this closed community, and what we might be able to bring forward to those on the outside.

The eighteenth months we spent at the Yard put us in connection to so many different working people, their families, their churches and schools, their hierarchies and their dreams. We, artists and community alike, all kept coming back because we were all discovering, learning, growing, seeing, telling, and listening to so many stories.

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard is (dis)connected to the city of Portsmouth by a bridge. On the final day of our 18-month residency, we had an honor guard of Navy men walk from two different sides of the city and Yard, meeting on the bridge. We tied together two ribbons to indicate a new feeling of hope between some of the opposing forces in the city. Oddly enough, the mayor who did the ribbon-tying had also done the ribbon-cutting fifty years earlier as a small child. One of the people who came up to me afterwards said: “Okay, Liz, you have been talking forever to us about the power of art. Now I get it. No one else in five decades has been able to close this bridge.”

How We Come Home from War

The Yard was a training ground for me for many ideas and ways to work. But it was also a set of clues about working amidst the military and civilians. And that was clearly an important part of Healing Wars. At the beginning of my research for that piece I was interested in three things:

1. What happened to women in the Civil War and in war today?

2. What happens to healers, doctors, and nurses who are in the midst of so much death and loss?

3. What happens to our soldiers when they get home?

Entering the project from the perspective of the 150th anniversary of our Civil War, and connecting it to our current conditions, I fully anticipated finding big differences. Yet I found more overlap than I expected, especially in the third question which became the driving force and the canopy for the other two. After all, whoever did come home came home as women, as healers, and as soldiers—all of them faced living with their actions and their dreams.

In the development and production of Healing Wars, as with the process of recovering the stories from the Portsmouth Naval Yard, what was most profound was the bubble-breaking overlap and connection between participants and community.

As we toured with Healing Wars, I also heard very personal stories from audience members. A man whose father had fought in the Korean War told me that the piece helped him understand why his father woke up screaming in the middle of the night for most of his childhood. A woman, who had been in Auschwitz as a young girl, thanked me for the beauty of Healing Wars and said “I have survived because I didn’t ask ‘why?’, only ‘what’s next?’” One man wondered before coming to see the piece, if he would see anyone healed because if not, he wasn’t coming; he was living with a brother who had come back from Iraq a triple amputee. Today in the era of Trump, much has been written about how we in the arts have been in a bubble. Perhaps, but in the development and production of Healing Wars, as with the process of recovering the stories from the Portsmouth Naval Yard, what was most profound was the bubble-breaking overlap and connection between participants and community.

Crossing Over

We recently performed excerpts of Healing Wars in Florida for a conference on arts and the military. In order to make the excerpts make sense, I inserted myself as a kind of artist-guide and narrator. I opened with this question: “If you weren’t there, how do you know what happened?” The rest of the thirty-five minutes was taken up with the various ways we tried to find out what did happen. The voices of veterans, Civil War reenactors, journalists, diarists, and letter writers made appearances. Every word comes from a primary source, except for the words of one character: she is a spirit, and her job is to help the dead on the battlefield cross over. When we meet her in the performance, she is tired; she doesn’t want to do the work anymore. Much of Healing Wars ends up being about her dilemma, and, by extension, ours.

Although my father didn’t die on the battlefield, I do enjoy thinking about him meeting this Spirit, just as he passed through. Perhaps, he lifted her own spirits a bit, as he was a wildly ecstatic kind of guy, even in death. And he might have carried her for a moment, his medic self so aware of her burdens. And then she would have set him on his path. He would have walked away in his uniform, the buttons pulling on his now much larger frame, and his purpose clear.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

While I found this piece touching ("a deep abiding love for comrades in time of risk, for buddies in times

of boredom, and for shared purpose when so much of life is diffuse.and thoughtful") and thoughtful ("shocked and thoroughly annoyed by the revolving doors between the Pentagon and other parts of the federal government"), I was taken back by the statement: "...the astronomical amount of money we spent on the war machine that keeps America safe."

For only a small fraction of the money spent each year on the war machine is to keep us safe; the rest is to enable The Empire to take sides in any conflict anywhere in the world, regardless of whether one side is truly better than the other, in order to enrich the companies and executives of the military-industrial complex.

Hi Neil. thanks for reading. Yes, i left that line in purposely and without irony as it conveys my own vexing questions regarding my personal politics in relation to any work i am making. i used to see it as primarily an issue in community practices but i am more and more aware of the dilemma in all art-making. When i began the project in the shipyard, i had some dear and close art friends who told me i shouldn't go as it would be supporting the military and we absolutely should not do that (in part for some of what you state). It raises all kinds of questions for me about any of the systems we work within.

In the case of the Docudances, i set up the structure so that my point of view was part of the reason for doing the dances. In the later work(s) my intent shifted, particularly when the structure involved so many other voices.

You raise an excellent point and makes me wonder what is going on when i write about the work. I was hoping it would come up in the comments. thanks for asking

Liz

When you were making Docudances, you could trust that people with various viewpoints would still watch, listen and participate. This allowed you to be increasingly inclusive in both your artmaking and your community work, and to continue the intertwining nature of that work. The artists who admonished you for "supporting the military" (although it was the people who worked for the military you were supporting--an important distinction...or?) in the shipyard still continued to come see the work and engage in its discussions. Would they today? Would any of us still engage with an opposing view, or even allow room for multiple views? Would we come see the work or would we boycott it? Never have your tools been more critical Liz!!!

Liz, always searching, not always for answers, but for possibilites, connections, resoltions...this is beautiful writing, resulting from probing the depths of what it takes to be human. The dances are gorgeous and touching, even in snapshots. Thank you , Liz, for letting others on to your pathways.

thanks Mary.

Thank you Liz for sharing this, as well as the dedicated work in creating such powerful pieces with high integrity and offering them to the various communities for enhancing greater understanding and facilitating healing.

thank you for taking the time to read this

What a wonderful post and powerful set of stories, insights and possibilities. Such good work Liz does. Grateful to hear it from her perspective, grateful for her work and vision. Marty Pottenger

thanks Marty. we are fortunate to have a the opportunity to keep an eye on each other's work over the years. grateful for that, despite the geographical distance