Todd London: Let’s talk about Down in Mississippi. In the play, three college students—a black man, a white woman and a white man—travel to the dangerous world of Mississippi in 1964 to register Negro voters. Along the way, they discover that before they can change the world, they have to change themselves. It’s really meaningful to reengage with that historical moment, especially now. I want to start by asking pre-genesis questions about it.

In the first speech, Jimmy, a Black Freedom Summer volunteer from the north, talks about two events that catalyzed his thinking about coming south and working in Freedom Summer with SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—one being Emmett Till’s murder, and the other being a young girl integrating New Orleans schools, which I take to be Ruby Bridges. He doesn’t name her, I think.

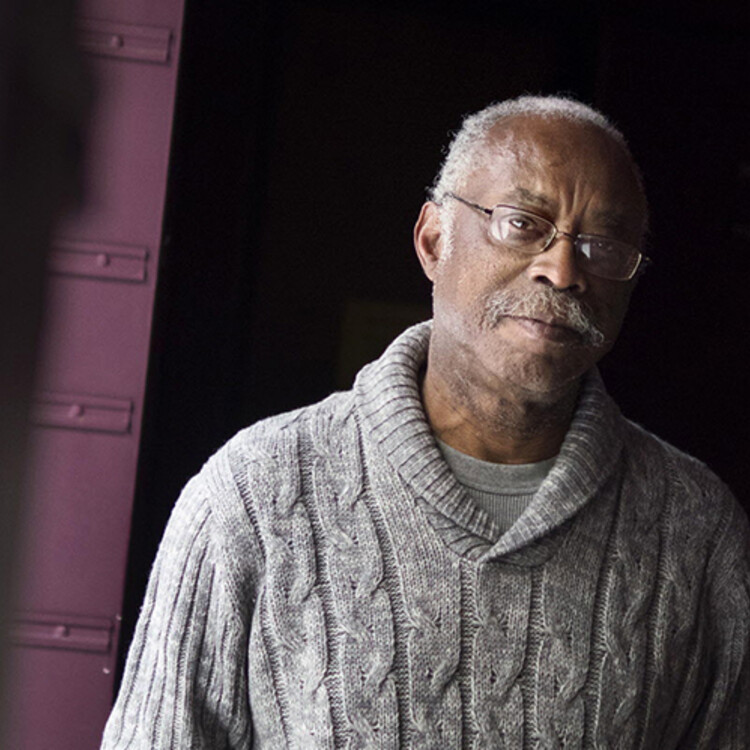

It made me wonder, where was Carlyle in ‘64? Is there some of you in that thinking? Or is that a historical moment? What was going on for you in 1964?

Carlyle Brown: Yeah, that was certainly a moment that I lived in. Down in Mississippi is a celebration of a movement that gave birth to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. I’m thinking in January 1964, I had a track scholarship to Kentucky State College. The reason that I was there, that’s a whole other story. But I had a track scholarship there.

In 1964, there were always conversations in the home of my grandfather, who was a Garveyite. He even had a ticket on the Black Star Line. He was my step-grandfather, and his son was a Black Muslim. I thought that all Black people had that conversation in their homes: what are we going to do? How do we live in this situation?

Todd: So there wasn’t a moment of awakening to the south? You were in New York?

Carlyle: Yeah, I lived in New York. That was a constant, but I would say that 1964 was critically different. The thing that I was near to, going to Kentucky State College, was Selma. It was a Black college, and people were recruiting buses, and activists were everywhere getting people to go to Selma.

I was on a track scholarship, and I was going to get on one of those buses. My coach, Coach Taylor, got on the bus and said, “We didn’t pay you here to do that.” I look back on that as thinking I didn’t really have enough really consciousness at that time to say, “Well, fuck you.” But that was certainly to come.

I wasn’t really there-there enough to be involved in that Mississippi Freedom Summer. But that was in everybody’s consciousness as well. ‘64 was really critical in so many ways in terms of the Civil Rights Movement.

Todd: You were the age of the characters in the play, because they’re all in college at that moment.

Carlyle: Yes.

Todd: Was that the first time you were going to live in the South, to go to Kentucky State?

Carlyle: Yeah. Well, my family was from South Carolina, and when I arrived in New York City, I was five years old. Somewhere around when I was maybe ten years old, they went back to the South. That’s again, a whole other story about the conflicting connections of people in the South who leave to go north and what that does to their relationships to what they consider home.

I existed in that generation, which is large. That particular migration, where people are really conflicted about the choice they made. About where they lived. It sucked, but that was their home. Now, they were in exile.

It’s domestic. Some people don’t look at it that way, but I feel that’s the conversations my family, that’s the way they spoke. As I look back, that’s not really something I was aware of at the time. But as I look back, I think that these were people in exiles having conversations about how do they exist in this new territory, which is not explicitly racist, but ambiguously racist? How do they adjust?

Todd: Right. I know you’ve written in other contexts about the difference between Southern racism and Northern racism, about that incredible second act of Pure Confidence, where suddenly we’re in Saratoga Springs. But we’re not going to talk about that. We’re going to talk about Down in Mississippi.

Okay, fast forward to 2008, when you’re working on the play. What kicks off the writing of this play?

Carlyle: It was a commission for the theatre department of Miami University of Ohio and their Center for American and World Cultures. Miami University of Ohio is in Oxford, Ohio, and encompassed now in Miami University of Ohio is a women’s college called Western College.

It was at Western College that the volunteers for the Freedom Summer project would train to go down to Mississippi to start registering voters. That’s where they did nonviolent training, and that’s where the dramatic episode—of course the three Civil Rights workers that were murdered, Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman—were there then at the beginning of that summer.

All their trainees had been there. All the volunteers that were there, all the white volunteers were there, and they were learning about voter registration, doing things they could do. There were freedom schools, and of course there was the Free Southern Theater. There were lots of things.

The way the movement was then, the way that people organized the movement was, everybody is not going to be a revolutionary or Che Guevara. But there was a structure that you could do whatever you could do. All you have to do was show up. If you said, “I don’t want to do that nonviolent thing,” then they would find something for you to do.

But as I look back, I think that these were people in exiles having conversations about how do they exist in this new territory, which is not explicitly racist, but ambiguously racist? How do they adjust?

Todd: You could organize. You could go and sign people up to vote. You could join the Free Southern Theater and go through the countryside—

Carlyle: Yeah, it was a way to organize people around their ambitions. There were really no distinctions of what contribution had value. The workshop was about sorting out those kinds of things and getting ready to go down to Mississippi.

While that training was going on in Meridian, Mississippi, a church was firebombed about people that were involved in registering. Forgive me if I don’t remember the exact context of why, but these three brothers, Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney, they went down to investigate. I don’t know what they thought they were going to do, but they went down to check it out.

Todd: Chaney was African-American and Goodman and Schwerner were white.

Carlyle: Right, they were white yeah. Suddenly no one heard from them, and they were anxiety. I reemphasize, they were getting ready to go down there.

It needs to be prefaced, with the idea of having all these white volunteers: it was run by SNCC to get the country to pay attention to the plight of Black people in the south. Particularly around voting, and particularly around Mississippi, if they recruited these white volunteers to go down and do that and face these dangers, then the nation would pay attention.

The guys didn’t disappear. The burnt car was found and then eventually the bodies. This came when it was really maybe a few days, no more than a week, before they had planned to get on the buses and go down to Neshoba County. This whole thing to get the country to pay attention… that became a horrible reality.

Then at the time, the workers went like, “Oh shit. We can get killed. This is real.” The whole thing then was to ask people, do they still want to go?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here