While Star Finch and Ellen Sebastian Chang officially made each other’s acquaintance in 2016, it wasn’t until 2020’s shelter-in-place that their friendship deepened via monthly phone calls where they spent hours trying to make sense of the state of the world. Now on the cusp of their first collaboration this summer, when Ellen will direct Star’s new play Josephine’s Feast at the Magic Theatre in San Francisco, these two creatives sat down for a conversation about the local Bay Area theatre scene’s recent, but long overdue, racial reckoning.

A Living Intergenerational Conversation

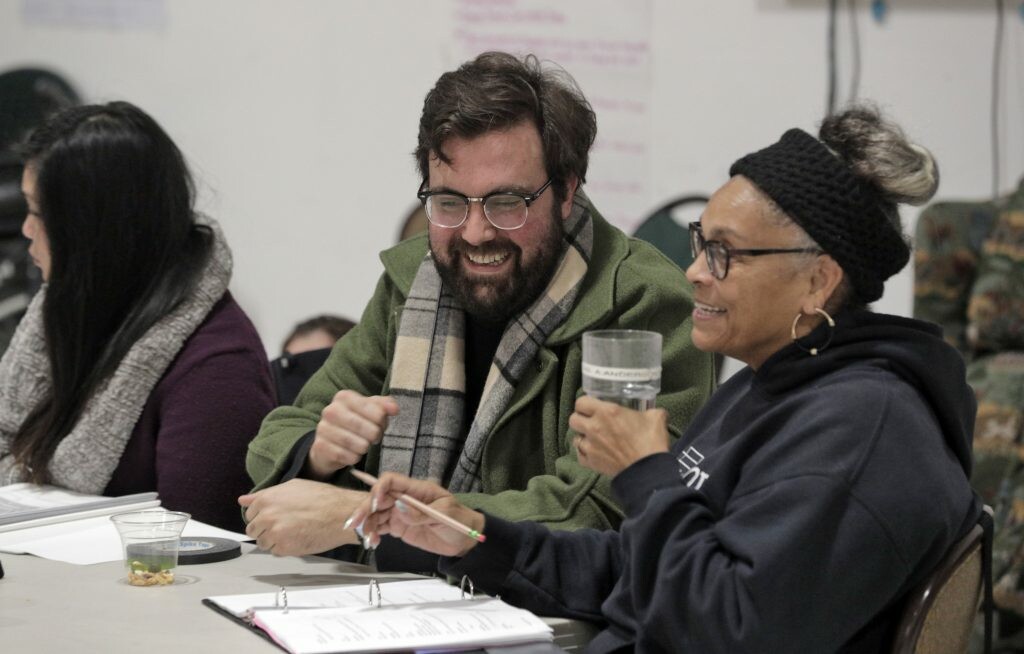

Bennett Fisher and Ellen Sebastian Chang in rehearsals for Candlestick by Bennett Fisher for Campo Santo. Directed by Ellen Sebastian Chang. Scenic design by Tanya Orellana. Costume design by Nikki Anderson-Joy. Lighting design by Maximilian Urruzmendi. Photo by Carlos Avila Gonzalez.

Star Finch: I really wanted to talk to you about theatre in the Bay Area for a number of reasons, but one is just the sort of depth and scope of your career, and the different roles that you’ve played within the Bay Area theatre scene.

Ellen Sebastian Chang: I’m hoping that you and I can have a dialogue about history, memory, and what we’ve been told, because I think these things are really important as well right now, how we continue to have a very living, intergenerational conversation.

Star: I know we talked about wanting to discuss the big shift in 2020 with the Living Document, which shook up the local theatre scene through anonymous testimonies of encounters with white supremacy within various organizations. But even prior to that, were there any shifts or differences that you experienced between, say, the nineties and the early aughts or the 2010s? Were there any shifts in theatre that way for you?

Ellen: Let me just go back to the nineties, because I think something happened at ACT [American Conservatory Theater] in the late nineties. I couldn’t quite remember, but I looked it up. ACT in 1997—in spring of 1997—got charged with racism, within the acting school. One of the things that was talked about was there was no full-time Black faculty. One of the students was quoted in a San Francisco Chronicle article as saying, “There are so many questions that haven’t been answered in our profession”—talking about theatre as a whole—“as to how does one deal with issues of cultural identity and distinction.” Then as we remember, most recently, Stephen Buescher—he sues, and settles. That was in February of 2019, before the pandemic.

Star: 1997 to 2019—wow, twenty-two years later and the same complaints. You mentioned the lawsuit against ACT in 2019, but even before that, in 2017, there was a lot of back and forth within the community around the Marin Theatre Company’s production of Thomas and Sally. I recall pushback around both the premise of the play itself and the response of the theatre towards protesters—the police being called on women who were out there holding space and lighting sage. And so, in getting ready for this conversation, I was really trying to recall the atmosphere leading up to the Living Document in 2020.

There was a lot of frustration and pushing back. But there was also the feeling that nothing was taken seriously enough to produce real material change. So that atmosphere made the Living Document, like you said, almost volcanic in its impact of just everyone vomiting up all of their trauma, all of their frustration, all of their experiences with white supremacy that they’ve had to swallow over the years here in the Bay Area.

White privilege systemically continues to control the resources.

Ellen: That’s right. I think vomiting is a good image, actually. Because now, we’re all standing in vomit. How do you bring unity, union, change, when we’re all standing in vomit? It is the vomit of the aftermath of ongoing COVID, designed racism, gun violence, the ever-increasing cost of living, and divisive ignorance of a nation still clutching historical amnesia and curated innocence. What is theatre in the midst of all of this?

Theatre, all of the arts, are a part of a historical arc, which includes access to funding and resources—real estate, healthcare, education, transportation, etc.—in the United States. I think that having some historical lens, no matter when we’re born in time, while it’s not everybody’s responsibility, it’s certainly someone’s responsibility. I’ve chosen this to be one of my responsibilities.

That Living Document, it was an incredible purging. Is the document already a past recollection? My concerns in these thirty-six months is what was potentially facilitated. Did it give “whiteness” time to shape-shift again? “We See You, White American Theater”; the rush to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) workshops; the shifting of small theatres to change artistic leadership—all of these institutional concepts, the language and strategies provided by the historical thought labor of Black, melanated, Indigenous folks… Did this provide the ideas for the performative language, with some optical illusions thrown in, to continue the status quo? What has changed on a holistic, systemic level? It all feels like another charitable act. Charity, which, as the years have gone on, I feel is “spiritual” money laundering, along with philanthropy.

White privilege systemically continues to control the resources. Yes, the Living Document was personally powerful. People needed to get that out of their bodies and to feel their experiences were not singular. In the purging and making it public through the anonymous internet, it also became susceptible to hijacking. I read on the latest Google Doc, the closed document, or it’s hidden, because white-presenting folks came in and hacked, and tried to change—

Star: —delete it. It’s always the same playbook of deleting the language, the historical record, the testimonials of the oppressed.

Ellen: What are the results in the aftermath? The Living Document continues as a redesigned and managed website with chapter sites in SoCal and a couple other cities. Okay. Where are we now? A name change. Land acknowledgement. More workshops and more white papers to report on the issues, data, statistics. Or a college degree in DEI. Those are manageable shifts. And ones that are part of a learned pattern of a white mindset rooted in authoritative gatekeeping while continuing to profit from the creativity of the marginalized.

I read a New York Times article about Broadway where a playwright said something like, “The gatekeepers are opening the gate. I didn’t imagine it,” and about how this particular play of this Black playwright was being brought to Broadway so quickly. He was like, “Oh, it’s like the gatekeepers are opening the gate.” Let’s listen to our own language. Why aren’t we questioning the gate? Not that the gate is opening, but questioning who owns, operates, and controls the gate. It is one of the challenges of this creative industry because we need that recognition and the potential financial rewards that come with these institutions.

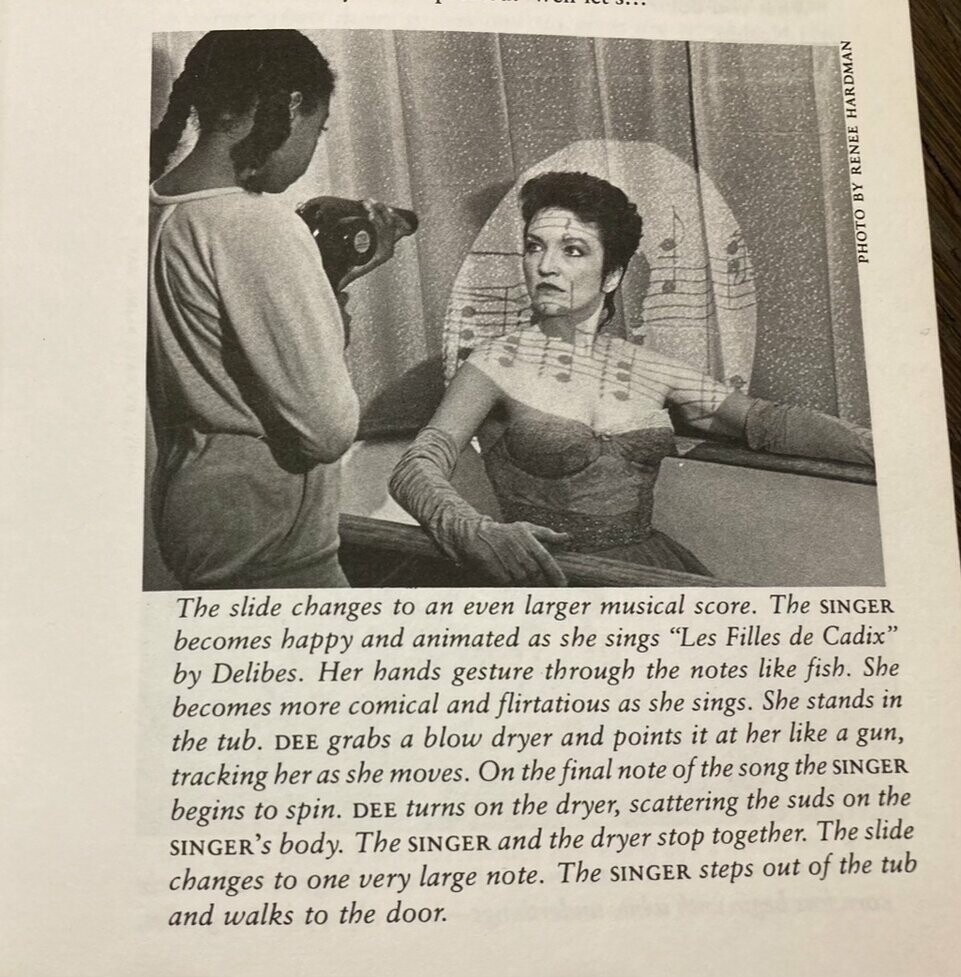

In 1982, Ellen Sebastian Chang’s directorial and writing debut called Your Place Is No Longer With Us (published in West Coast Plays) was created in a Victorian mansion and told the story of the coming of age of a ten-year-old biracial girl. A meal of black-eyed peas, mustard greens, and corn bread was cooked throughout the performance and served to the audience at the end of the play. This work was the beginning of Ellen’s interest in children, as well exploring dialogues in regard to race, in particular mixed-race identity and strong female-identified images. This is an image from the walk-in bathroom of a private home on Divisedero near Haight Street in San Francisco. The production was designed in collaboration with lightning designer Jack Carpenter and visual effects were done by Peter Maravelis. The actors are ten-year old Zorana Edun and Janeen Wyatt. Photo by Rene Hardman.

Star: A lot of artistic directors have stepped away. Both those who held the position for multiple decades and those who were only a few years in. That’s suddenly not the hot job anymore.

Ellen: That’s right. There’s a recent article just published this year on Shondaland.com heralding the Black women artistic directors reshaping theatre. The first paragraph mentions immediately the “massive obstacles like ‘white flight’ of donors, and in one case, a death threat.” Part of what the article speaks to is these very capable and creative Black women striving for equitable change, but there’s people who don’t want to subscribe—yes, a play on words—to this change.

The past three years allowed me to understand ordinary racism/sexism/classism. The Bay Area, really much of the West Coast, is steeped in it. It’s not the overt Klan-type. It’s not something epic. It’s run-of-the-mill.

My thinking is still sitting on these nesting thoughts: the “shutdown” allowed me to become curious again. I began listening and learning more from the historical and current experience of disability activism. First from the direct actions of visibility and access, followed by reflecting on the words “impaired” and “disabled.”

Blackness, queerness, Indigeneity, and poverty are historical impairments in this capitalist livelihood-over-life path. And embracing disability as a lens to view how these oppressive systems control people, disabling entire cultures, groups, and individuals’ social-emotional intelligence. How does white supremacy disable life? How does it defuse it? Well, ordinary oppressions create value judgements of worth based upon impairments—physical, mental, spiritual—and disabling does it by abandonment, shifting the rules of engagement, planting seeds of doubt about your personal abilities, forcing you to be legible for whiteness/ableism/mainstream as normative, upheld with the tried-and-complacent verbiage of “these things take time and be patient,” boot-strapping, grind, hustle, 24/7 productivity, absurd forms of competition and scarcity. Therefore reciprocity, reparations, and repair are all too complicated to consider in a system that perpetuates erroneous fears that uphold blame, “not my” responsibility, and revenge myths.

Star: Mm-hmm.

Ellen: And in a liberally educated culture the disabling is crafted creatively within an agreed-upon language that forges and rewards a standardized mythology. Theatre has roots based in mythology, therefore the mythology around women, around melanated people, poor people, old people, impaired people, this modern mythology is much more dangerous because it’s designed to be very seductive and crafted, and to massage the illusions.

Visiting artist Ellen Sebastian Chang in conversation with Africanfuturist Nnedi Okorafor at Stanford University, 2023. Photo credit: John Liau.

Star: I recently saw land acknowledgements on a prison’s website. My brain instantly stopped loading after reading it, unable to form a next thought. Anyway, I’m really struck by the language you used earlier around “disabling” in relation to white supremacy.

Ellen: It’s something I’m just starting to explore.

Star: I think you really hit it on the head with the disabling around community. Like San Francisco, you talk about the myth of San Francisco, the Bay Area. I can only speak on San Francisco, being a little kid here in the eighties and watching the AIDS epidemic unfold, the activists, and in the theatrical forms of protesting in the streets.

I think about Ntozake Shange workshopping For Colored Girls in the Haight-Ashbury, jamming and creating with her community of poets/dancers/musicians in San Francisco—Jessica Hagedorn, Ed Mock. She wrote about how the energy of the scene nurtured her work, alongside the emergence of various women’s studies/ethnic studies courses at the local colleges that artists were learning from and responding to. So many creative and political movements in San Francisco history would literally not exist without that freedom of finances and housing. San Francisco as a city of refuge that welcomed people running away from whatever they were running from, and you could arrive and survive here.

It’s clearly intentional the ways in which the tech boom was used to dismantle this city financially through real estate in just a decade. And of course city leadership was complicit. I would say Airbnb and out-of-state real estate speculators really stole the last gasp of breathing room left. They made it next to impossible for that next generation of working-class youth to step out into affordable housing and survive well enough to do the things that their soul is actually here to express creatively or politically. Now everyone’s number-one fear is ending up homeless.

Ellen: I moved to California in 1970 I was fourteen. I was an unsupervised teenager running pretty wild on the streets of Berkeley and the Cal Campus. My best friend and I got an apartment together at age seventeen. Rent was affordable. We had a two-bedroom apartment on McKinley Street, right behind Berkeley High School. It was $175 for two people. We worked part-time, socialized, and still had the spaciousness to attend community college, which is all I could afford.

When I started at Laney College in Oakland, I was a nineteen-year-old young Black woman, helping to move new lighting equipment to the current standing theatre. I wanted to be a lighting designer. I don’t recall how much I paid for my two years at Laney. I can’t remember. It was that negligible.

Star: Right.

Why aren’t we questioning the gate? Not that the gate is opening, but questioning who owns, operates, and controls the gate.

Ellen: When something is really exorbitant, costly, you don’t forget that stuff. That’s why people talk about it: “I’m trying to pay off my student debt for when I went to drama school or law school.”

I got hired by the CETA program—Comprehensive Employment and Training Act—a paid job at Berkeley Stage Company as a lighting and crew person. And with low rent and food stamps this was truly the beginning for me of scraping together a creative, interesting life.

I’m going to shift forward to where I felt or noticed a shift in the arts, which began during the Reagan administration’s National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) cuts and which continued with Bush Sr. and Senator Jesse Helms. The attacks all centered on individuals—the NEA Four: Holly Hughes, Karen Finley, John Fleck, and Tim Miller. Karen Finley being a radical, white feminist. Holly Hughes, lesbian. Tim and John, queer men.

It’s AIDS that also helped fuel the need for censorship, and spending taxpayer money on art that was considered obscene, immoral, lacking family values... The individual was problematic. The individual queerness, the individual naked white woman’s body. Karen Finley’s performances, which got lied about, mythologizes something where she’s so sexualized and pornographic.

At that point, the NEA started to internally work around ideas of professionalizing theatre—“professional” in my perspective becomes code for changing an artist’s relationship with organizations and how their work is funded and presented. Artists become institutionalized and the working process becomes more “managed” in the guise of workshops, readings, audience feedback, more workshops, and some of the work never goes beyond the workshop.

And we forget how we became this right here… Artists are willingly institutionalized. Artists need organizations to apply for grants. Now there’s no more individual grants. The direct support to artists or small artist-run companies become less and less, and then now they’re working with predominately who? “White” mindset institutions, because the smaller, less-resourced venues of the past became memories or have been slowly disabled: Ed Bullins Theatre, Oakland Ensemble, and some that I actually can no longer recall off the top… Lorraine Hansberry Theatre doesn’t have real estate. Its founders had such a strong vision but the theatre was not supported financially in the same manner as ACT.

Bayview Opera House and SOMArts are holding strong and currently appear vibrant. San Francisco Arts Commission, which owns these facilities as well as four others. Berkeley Black Repertory is a property whose future is a mystery to me.

Photo from “Episode 11: Black Womxn Dreaming ‘divine the darkness’” in House/Full of Blackwomen, a multisite, multimedia, ritual dance theatre project addressing the displacement, well-being, and sex trafficking of Black women and girls in Oakland. Created in 2015 by amara tabor-smith in collaboration with director Ellen Sebastian Chang and a collective of Black women artists, abolitionists, and community members. Set in various public sites throughout Oakland over a seven-year period (2015–2023), this community-engaged project is performed as a series of episodes that are driven by the core question: “How can we, as Black women and girls, find space to breathe and be well within a stable home?” Ashara Ekundayo Gallery and a secret location in Oakland, California, 2019. Photo by Robbie Sweeny.

Star: It’s all so intentionally exhausting, from top to bottom.

Ellen: It’s exhausting. It’s exhausting! You just take the whole spirit of play out of every human being, and that’s why artists, we’re so siloed. Who are our audiences going to be in the future? Because if everybody’s a creative and everybody’s an influencer through TikTok, then who’s listening? Then we’re just fighting for an audience. What we’re fighting for now is attention. Who’s coming to my show? How are they affording my show? Is it just artists viewing artists? Is my work no longer valid if it is not expressing urgency for my community? Who is my community? Am I social worker/artist?

With all these questions spinning too, I really am no longer interested in arguing with whiteness. I’m not. It’s like whiteness is going to do its thing, and whiteness is not here for the melanated. Anyway, all right, Star. Here we be.

Star: Here we be indeed.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here