The N-Word on Stage

Jordan Cooper was reading the autobiography of Lucille Ball in Bedford Junior High in his hometown thirty miles outside of Dallas, Texas, when a passing classmate knocked it out of his hands and said, “What you reading,” and then added what we are going to call the n-word.

“I pushed him against the wall,” Cooper recalls. They were both brought to the principal’s office.

Less than a decade later, Cooper, now 22, is an actor and playwright living in New York, who recently starred in a play he wrote, Ain’t No Mo’, that repeats the n-word some thirty times.

This is not any kind of contradiction to Cooper. “It’s important to reclaim the word,” he says, “because it’s still being used, and still being used to hurt people.”

How far can a work go in order to be historically accurate, or (if a contemporary piece) authentic? How alienating are stage characters allowed to be? How much must playwrights and directors and producers keep audience sensitivities in mind (does it depend on the particular audience?) or is their only mandate to present the truth? Whose truth? Does it matter who the “truth teller” is?

“The n-word may be the most divisive word in the English language,” wrote the editors of the Washington Post, in an interactive project on the n-word that the newspaper put together in 2014, the year the National Football League banned the use of the word on the field.

In part it’s a generational divide: “That’s how many black Americans of my generation talk,” Cooper says, although adding: “I don’t say it in my normal speech.” In part it’s a cultural/racial divide. “If you don’t come from a culture that uses that word benignly you shouldn’t use it without understanding its weight,” Cooper says.

For all its divisiveness, the use of the n-word on stage is fairly common nowadays. Much of its use is without controversy. The Broadway production of August Wilson’s Jitney includes the word playfully employed by the African-American characters with one another; last year’s production of Turn Me Loose, a play starring Joe Morton as the comedian Dick Gregory, used it more than fifty times.

New York playgoers have not quarreled with the word even when used as a racial slur. One startling example is the 2008 all-black Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hat Tin Roof, when James Earl Jones as Big Daddy uttered the word as written. “Why would you censor something that was actually said and done at the time?” says Alia Jones-Harvey, who produced that play (as well as subsequent all-black productions of A Streetcar Named Desire and The Trip to Bountiful). Indeed, Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout went as far as to slam the omission of the word from the current Broadway revival of The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, a comedy about cynical Chicago newspaper reporters of the 1920s, as undermining the play’s “tungsten-hard tone.” Teachout explained: “In the original play, the characters use the n-word repeatedly, and they do so for the best of reasons, which is that its casual use dramatizes their no less casual racism.” The director of the revival, while keeping an epithet for Italians in the script, erased the slur against African-Americans, “which is an all-too-clear indication of his squirming discomfort with the thousand-proof ferocity of Hecht and MacArthur."

But the wrangling over a production of Ragtime in a New Jersey high school demonstrates that the use of the word on stage remains, as Cooper and others put it, “complicated”—and confusing, and dizzying in the array of questions it provokes, among them: How far can a work go in order to be historically accurate, or (if a contemporary piece) authentic? How alienating are stage characters allowed to be? How much must playwrights and directors and producers keep audience sensitivities in mind (does it depend on the particular audience?) or is their only mandate to present the truth? Whose truth? Does it matter who the “truth teller” is?

I will not move

From where I'm standing

Till what's mine is restored to me

I'm not some fool

I'm not their n…!

A character named Coalhouse Walker Jr. sings this in a song entitled “Justice” from the musical Ragtime, after a racist fire chief named Will Conklin has destroyed Coalhouse’s brand-new Model T Ford out of hatred and spite. Coalhouse’s search for justice sets off a series of tragic events. The Tony-winning musical, based on the 1975 novel by E.L. Doctorow, focuses three on families—one of white Protestants, one of African Americans, and one of immigrant Jews—at the turn of the 20th century. The fire chief is the one who utters the racial epithet most frequently.

The Cherry Hill High School East in Camden County, New Jersey had scheduled Ragtime for their springtime musical when the mother of a black student who is a stagehand for the production lodged a complaint. The head of the local chapter of the NAACP, Lloyd Henderson, then wrote to the superintendent of Cherry Hill schools, Joseph Meloche, who announced on January 20th, that the slur would be removed from the script. “We apologize for any negative impact that the potential inclusion of the racist language had on members of our community.”

The theatre community at large reacted, arguing that the ugly language was intended to drive home the ugliness of the era. "When you sanitize history, you forget it, and then it happens again," commented Lynn Ahrens, the musical’s lyricist, during a panel discussion on Ragtime at BroadwayCon.

“I understand why they would be upset, given the tenor of the times and what’s been in the news,” Brian Stokes Mitchell, who portrayed Coalhouse Walker Jr. in the original, 1998 Broadway production, told Howard Sherman of the Arts Integrity Initiative. “But that is what the show is about…It is the ugliness in Ragtime that gives the cathartic power to its tragically beautiful ending.”

Besides, theatre advocates said, the school does not have the legal right to change the script without permission of its authors.

The latter argument seemed to have been persuasive (Meloche said the show’s distributor, Music Theatre International, told him it had to be performed as written or not at all), when a week later the superintendent reversed his decision. Surely helping as well were the Change.org petition of some 2,000 signatures urging restoration, the 74 percent in a local newspaper poll who favored inclusion of the n-word, the protests by the students themselves, and the extensive outside attention. The superintendent said there would be an effort at educating students about prejudice. “We will make it abundantly clear that we loathe the n-word, that we despise this most vile of words in our language…We believe we can educate using difficult subject matter presented in a safe, sensitive way.”

“It's definitely a learning process," responded the NAACP’s Lloyd Henderson. "But we've been learning this lesson for years.”

Poet, playwright, and lyricist Langston Hughes, a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, wrote about the n-word in 1940:

Used rightly or wrongly, ironically or seriously, of necessity for the sake of realism, or impishly for the sake of comedy, it doesn't matter. Negroes do not like it in any book or play whatsoever, be the book or play ever so sympathetic in its treatment of the basic problems of the race. Even though the book or play is written by a Negro, they still do not like it.

The word “sums up for us who are colored all the bitter years of insult and struggle in America,” Hughes concluded.

“I don’t disagree,” says Kevin Free. “But it’s so complicated.”

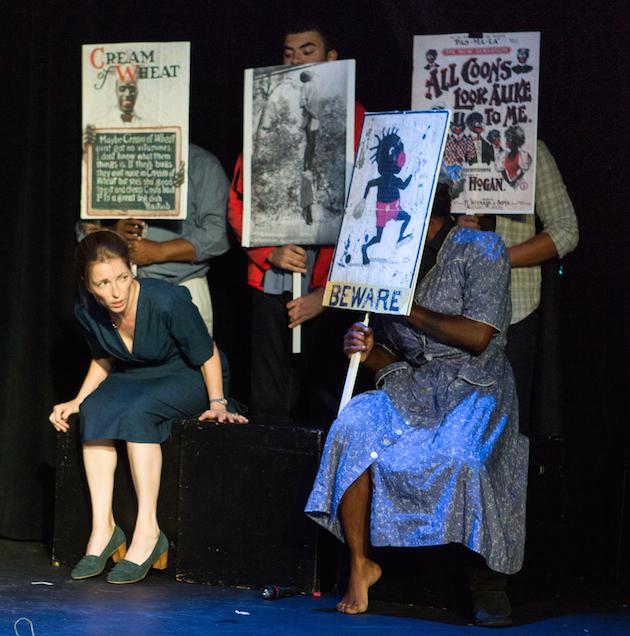

Free is an actor and playwright who tackled the complications head on with his play, The Night of the Living N Word.

The idea for the play dates back to 2007, when Free watched a YouTube video of the NAACP at its convention in Detroit holding a funeral for the n-word. He responded initially with a two-minute play for the New York Neo-Futurists that was a spoof of a trailer to a horror movie.

Free expanded The Night of the Living N Word to a full-length play that was presented at the 2016 New York International Fringe Festival. It is a campy, chaotic comedy that takes place in an old plantation off the coast of Georgia, where Barbra, the daughter who rejected the Confederate values of her family and married a black man, is returning home to celebrate the birthday of her biracial teenage son. Barbra has banned the n-word from the household, and from her hearing, and resorts to some over-the-top punishments for anybody who defies her, including (especially?) her (black) family and her (black) servants.

The script includes the n-word dozens of times. There was calculation here: The audience becomes “desensitized to the word, and sees it in the context of a comedy,” Free explains. “And then, at the end, another black man is shot.”

Among the serious points Free hoped to make with his play is that Americans “focus on the word, but the attitude we have towards black people—and black men in particular—does not die. The word is not as important as what’s behind the word.”

Free also explores the differing views of black and white America towards the n-word. This difference plays out in various ways. Recently, when a panel of playwrights at Cherry Lane Theatre was asked whether there's anything they don't write about, Lucy Thurber (The Insurgents) replied that she overheard two men talking, and "every other word was the n-word. It was like an opera. It was gorgeous. But I would never write that....Respecting other people's narrative is important."

“I appreciate her saying that,” Free responds, when told of her comments. But he adds: “I do believe that we have to find a way for people who are of white culture to be allowed to write about other cultures. I don’t want white people to say ‘I can’t write black characters.’”

Yet the mixed audience for his play at the Fringe made some African-American audience members uneasy with the copious use of the racial slur. “One woman said to me ‘I watched the play, and the white people were laughing when your cast was using this word. I was feeling angry that you were using this word to entertain white people. But then at the end of the play, I thought more about it. You made me think about what the word is and what it means.’”

As it turns out, Free wound up uneasy as well. “After doing the play, I told myself I’m not going to say this word for a while, because it took a toll on my soul—not just the word, but the ideas around it. While we were rehearsing, a black man who was protecting an autistic kid was shot by a police officer in Miami.”

Free is also the producing artistic director of The Fire This Time Festival, a New York festival of new plays by and about African-Americans, which just completed its eighth year. The festival presented Jordan Cooper’s Aint No Mo’. The play takes place on Election Day, 2008 and set in a funeral parlor. A preacher (portrayed by Cooper himself) is delivering the eulogy for Right To Complain.

“I had conversation with a lot of white people that racial problems will be over now that Obama was elected,” Cooper says. “I was making fun of that—in the play, we’re crying because we can’t complain any more.” He started writing the play after the White House Correspondents Dinner last May, when Larry Wilmore gave a speech that concluded “Yo, Barry. You did it, my n….”

“Part of me reacted by saying—why would he say that to him in that space?” Cooper says. “And then I started to think, well why not?” Cooper began to see that Wilmore was saying, “’This president is mine.’ There was a sense of ownership; I finally have something in this country that’s mine.”

“There is such power in taking back something that was negative,” Cooper says about the n-word. “Dick Gregory made the word the title of his memoir. He told his mama that if she ever hears that word again, they’re just promoting his book. On the flip side, Maya Angelou said that even if you dilute poison with sugar, you’ll still die.”

Playwright Kelley Nicole Girod, the founder of The Fire This Time festival, believes that “context is everything. Whatever you’re presenting on stage you have to take responsibility for.”

If an artist uses the word, Free says, “You have to be prepared to defend yourself, and have a discussion about people’s assumptions about you as a person.”

Cooper agrees: “I can tell when somebody is using that word because they can. It’s an entitlement thing. There’s no sense of what it means to other people.”

Free seconds that, citing film director Quentin Tarantino: “What makes him think he has the license to use the word so much in his movies? Why does he feel that he relates so much? I don’t think he’s hip. He gets on my nerves.”

At a time when many fear a heightening of racial targeting and a lessening of government protection, Free says he sees why some parents in New Jersey might have objected to the language in Ragtime. “A lot of parents feel the need to separate their children from the pain of racism for as long as they can. I understand that. “But there’s a point to us hearing the words on stage. You can take the language out, but it doesn’t lessen the impact of the racism.”

If the n-word is buried for good, Cooper says, “They’ll just come up with other words—like ‘thug.’”

“The word is not embedded in the culture,” Free says, “but the culture is embedded in the word.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I want to link to my review of Big River (which I saw after this story was posted) because the musical uses the n-word -- as, of course, does the novel on which it's based, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. https://newyorktheater.me/2...

A most illuminating and wide-ranging article, and I'm most grateful. I'd been wondering about the question in connection with a course I'm teaching about musical theater, and in particular in connection with _Show Boat_. The original libretto begins, "N-s all work on de Mississippi." The 1936 James Whale film changes that to "Darkies all work on the Mississippi." the 1951 MGM film changes that to "we all work on the Mississippi" (which feels wrong to me, oddly similar to "all lives matter" as a slogan). Other theater productions no doubt make other choices. I don't have a clear sense of what's needed here, other than, as noted, not liking the 1951 MGM revision.

I've read that it was Paul Robeson who insisted that the 1936 lyrics of Ol Man River change it to "darkies." In his concerts, he left out that section entirely, and changed the rest of Hammerstein's lyrics too.

For example, he changed:

Ah gits weary / An' sick of tryin'; / Ah'm tired of livin' / An skeered of dyin',

to

But I keeps laffin'/ Instead of cryin' / I must keep fightin'; / Until I'm dyin'

I am a playwright and a film maker. I'm currently working on a piece entitled "The Black Bullet Dichotomy" and there were opportunities in there to use the word. I went a different route. And at the same time I saw "Fences" and I thought that August Wilson handled the word masterfully. For me it's do you know what you're saying? And if you do is there a malicious intent? In the piece I'm writing now there is no need for the word in the next piece there might be. Again it lies with the intent.

Thanks for this article, it is a good articulation of an important issue.

It occurred to me while reading that we really struggle with whether to represent the n-word on stage, but we don't even flinch at representing gruesome murders and rapes on stage. I am not sure why that is, but in once sense it can be seen as a testament to the awesome power of language.

On the other hand, it might be that theater as an art form is more confused about language being _represented_ rather than _present_ on stage than it is about violence or abuse being represented but not present, which makes sense, because in order to pretend to stab someone on stage you do something physically different than if you were actually going to stab someone, while it appears as if pretending to be a character saying a word seems to be a very similar action to actually saying it - that is, the gross physical motion that the actor goes through to produce the sound is the same as that gone through by a person in the street producing the same sound. But everything on stage is representing something else. (There's a quote about "even a chair on stage is pretending to be a different chair"). And even spectacle gets blurry sometimes. The actions an actor goes through when they are pretending that their character shoots someone is essentially the same as a person on the street would go through to actually shoot someone. The gun even looks the same to the audience, but in fact, it is a different object, despite _looking_ like the same object. I wonder if the same is true for the n-word? Is the n-word on stage, in theory, "not loaded" the way a prop gun isn't loaded (one hopes) with real rounds? And if so, why is the illusion so much more powerful - that is, why are we disturbed when someone says the n-word, but we never call 911 when someone is "shot" on stage?

"It occurred to me while reading that we really struggle with whether to

represent the n-word on stage, but we don't even flinch at representing

gruesome murders and rapes on stage."

Very well put.

You've opened up a fascinating topic. One way to further the conversation is to ask: How does live theater differ in this regard from movies? Does the violence in a movie mean more and the language less?

In a theater, you're breathing the same air as the performer/character. And, also, the theater is (almost always) more representative than realistic? Does this require the audience to fill in with their own imaginations -- and being in your own head makes it feel more personal?

Yeah, the similarities and differences between film and theater are an interesting topic for sure. I am only sort of a film theorist, I mostly focus on theater, but it is hard not to draw the analogies - they seem so obvious.

The violence on stage is usually not as mimetically realistic as it is in film, I agree. Though on stage it is more real, in a way. In the sense that what is happening is really happening right there in front of the audience, at the same time as the audience is watching it. That is part of the appeal of theater. (Interestingly, a lot of theater folks think of film as obviously more real, while a lot of film people think of theater as obviously more real). But, it is also equally unreal since just like film, the story being told is not real - it is a story about an alternate world. Even under realism, the world of the play is one in which these things happened in this way. Even in a play about real historical events, it is an alternate world in which at the very least, people looked different than they did in the world in which we all live, and sound different, and even if direct quotes are different, they are probably said in a different way. And from that alternate world, we draw _analogies_ to our world. To get back to the n-word discussion (though since violence is my focus both as a practitioner and as an academic, I easily get drawn there. And also, the n-word's use _is_ a form of violence) it is the analogies to racism in the real world that are "too close to home" even in the alternate world of the play.

By coincidence -- or maybe it's just in the zeitgeist -- here's a NY Times article on how three playwrights handle the gun violence in their new plays about gun violence.

Courtney Baron says: "Violence is more about entertainment than it is about the reality of what happens to people. It’s like sex onstage. It doesn’t work. I studied with Romulus Linney at Columbia, and he was always like: “Don’t put a gun onstage. It’s going to be horrible.”

https://www.nytimes.com/201...