Glenn Davis: What has it been like taking the helm in the middle of everything that’s happening? I imagine if you saw yourself leading an institution that it would not be under these circumstances.

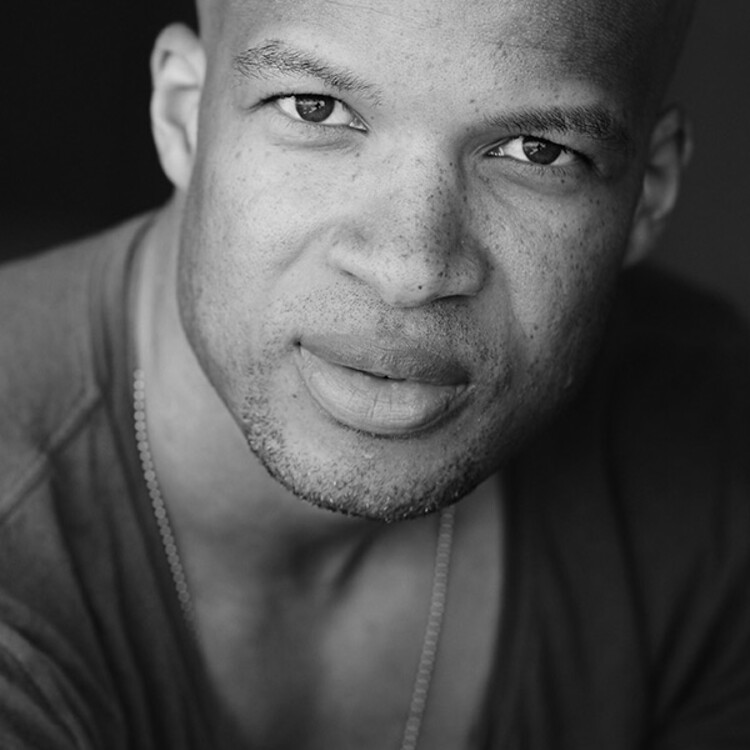

Ken-Matt Martin: It’s interesting. In many ways I felt like my entire career led to this moment, right? When I think back—shout out to [Robert] Hupp who’s now at the artistic director at Syracuse Stage, who was the artistic director with the Arkansas Rep. When I was like fourteen, he took me under his wing and let me just follow him around and ask him questions. That really planted the seed for me of wanting to be an artistic director one day.

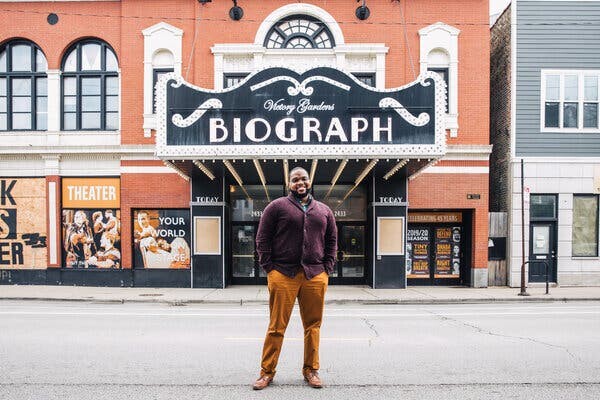

I’m for four and a half months on the job right now, and honestly it kind of sucks. Not the job itself, but that I had to take on this job in the middle of a global pandemic. I’m coming off a very public, tumultuous leadership transition in my institution, which creates problems. In addition to that, there is this rising labor movement within our industry that I am a passionate supporter of. Now here I am, taking over a theatre that is facing what I like to call white flight of donors and board members. There are a lot of people who’ve decided that since me and some of the other leadership happen to be Black that they no longer want to support this place. We’re watching a dwindling market of donors who are taking their money elsewhere because there are new leaders who look like you and I.

So these first couple of months have just been really, really hard. I am hopeful for the future, but that’s how it’s been for me so far. What is it like for you at this point?

Glenn: So last week was my first week, and what you said is absolutely true. There’s so much to navigate in this moment before you even get to the fact that I’m Black, right? There’s a world that is changing very quickly. I’m not casting aspersions, but there is a reckoning and a conversation being had about people who’ve historically garnered and had proximity to power.

Then there’s the dealing with, like you said, essentially white flight. I’ve been warned several times by folks. Our counterparts who are not of color don’t get that same questioning. So that’s something too essentially for us to navigate as well.

Ken-Matt: I tweeted about this recently. [Stephanie] Ybarra, a colleague at Baltimore Center Stage, had retweeted someone who had written about being at a party with a group of their mother’s friends in Baltimore. They had unsubscribed from Baltimore Center Stage because there were too many Black shows. Steph retweeted it and said, “If I had a dollar for every time I got feedback like this.” And then I tweeted about my story about what was said to me by a donor.

All of us have had to say goodbye to racist folk who, in many cases, are the types of folks who voted for Barack and consider themselves liberal, right?

Glenn: That’s the insidious lack of nuance in the conversation around race. But everything is not racist. Every time someone does something that seemingly is pejorative around race doesn’t mean it’s racist. I tell this story often. Years ago, a friend and I were talking about actors. He was like, “Who’s your favorite actor?” I said, “Denzel.” And he said, “Oh, cool.” And I asked him, “Who’s your favorite actor?” He said, “Daniel Day Lewis.” I was like, “Oh, dope. What did you think of Denzel?” And then he said, “Definitely the best Black actor.”

Ken-Matt: Someone said this to your face?

Glenn: Yes. This is years and years ago. But I remember when he said that I was like, “Dude, if you’d have said to me what do I think of Daniel Day Lewis and I would have said definitely the best white actor, what would your response have been?” And he went, “Oh, shit.” So what I did was show him how he added a racial component to a conversation that had nothing to do with race. That’s what they do to us when we’re coming to lead the institution and they say, “Hey, don’t do all Black plays next season.” I’m like, “I’m leading the institution. You put race in the conversation—”

Ken-Matt: I hear you. What I’m hearing are the moments where we want to call people in, as I’ve experienced it with my dear friend Carmen Morgan at artEquity. The way that I’ve seen her utilize this practice, it’s something that’s rooted in love.

Yet I don’t want to let anybody off. There’s still some racist stuff going on. A call in is not going to fix that because racism is connected to power. To be clear, you and I are in positions of privilege and power in these roles, yet I think many folks in the industry don’t always take the time to look at the entire power structure. So I agree with you that there may be opportunities to call some people in with love, yet there are many of us—especially Black folks—who are tired of feeling like we have to be the ones correcting folks. It’s also within our purview to not have to do that when we don’t want to.

We’re watching a dwindling market of donors who are taking their money elsewhere because there are new leaders who look like you and I.

In my case, that donor had made a commitment to give a gift and had only given half of their gift. I was trying to connect with them as a new leader to see if they were still going to give the rest of their gift before the end of the fiscal year. That person warned me not to do too many Black things before the donor decided. That’s racist. Let’s call it what it is. They’re wielding some power in the form of their financial capital. So I don’t want to let those folks off the hook either. There’s no call in moment there.

Glenn: Thank you for making that distinction. In my case, that was a moment to say, “Hey, I don’t think you heard yourself. I don’t think you quite heard what you just did.”

Ken-Matt: And he corrected himself, which is key. That’s the difference.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for sharing this great conversation. As a longtime fan and occasional collaborator at both theaters, i look forward to watching and supporting your work!