Since its founding by Jean Vilar in 1947, France’s Avignon Festival has always been linked to political engagement. This year, the main focus was on gender, though some of the plays highlighted other issues around the world, like the refugee crisis. It so happens that attention was also given to staging “the document”—where real-life events, people, or documentary material, such as interviews, articles, reports, and correspondences, are used as the basis for storytelling.

Yet the plays presented cannot all be confined to the genre of documentary theatre, or even to its related forms like verbatim theatre, investigative theatre, theatre of witness, and other such titles. Documentary theatre has evolved over the years, and today the genre goes beyond pure documentation: it’s about questioning the meaning and significance of truth and information. How can truth be revealed in an era when the immense flow of information disfigures reality—augmenting it or diminishing it—making accessing a single truth almost an impossible task?

Four productions that played with staging documents were included at the Avignon Festival: Il pourra toujours dire que c’est pour l’amour du prophète (He Can Always Say It Was for the Love of the Prophet) by Gurshad Shaheman, La Méduse (Méduse) by Les Bâtards Dorés collective, Pale Blue Dot by Étienne Gaudillère, and La reprise – Histoire(s) du théâtre (I) (The Repetition: History/ies of Theatre (I)) directed by Milo Rau.

When it comes to categorizing these shows, though, not all of their directors were comfortable with the documentary label. Rau doesn’t see theatre as a “medium for transferring information,” and although most of his plays are based on sociopolitical events and tragedies like the genocide in Rwanda (Hate Radio) and the Jihadi movement (The Civil Wars), he is more interested in the cathartic process of his work rather than focusing on the documentary aspect. Gaudillère, on his end, seemed reluctant about qualifying Pale Blue Dot as “documentary theatre.” He is more interested in using real-life material and sources like newspaper excerpts, TV interviews, and classified reports to make theatre, while at the same time avoiding didacticism, which is typically a crucial component in the genre.

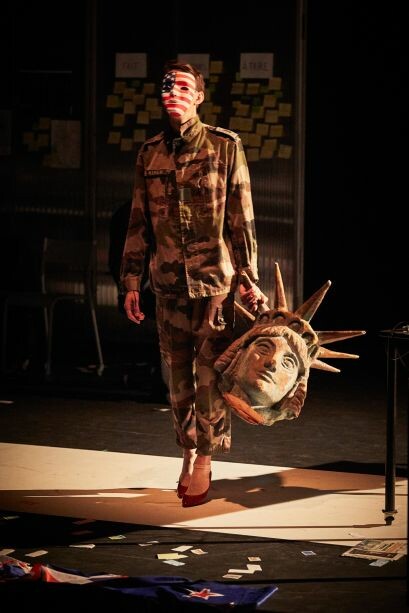

Presenting the “real” as “true” became, in the four plays mentioned, an act of “document performativity” where some realities were communicated to the audience through multiple standpoints and truths. Each of the play’s directors worked with their source document (or “the document”) using different aesthetics and tools—which ranged from transforming the space into darkness where an oratorio of monologues proliferated (Il pourra toujours dire) to using the form of the tribunal as an essential plot device (La Méduse) to combining naturalism with live video projection (La reprise) to inundating the stage with a spectacular flow of information (Pale Blue Dot).

Shaheman’s play, Il pourra toujours dire, focused on the hardships of people who have been exiled, notably artists and those who belong to the LGBT community. After gathering testimonials from the refugee and migrant encampment Calais Jungle in France, the director used the material to write monologues, which were then recited on stage by performers. These artists played the role of “depositaries of the texts,” according to Shaheman, who describes his work as an “oratorio of voices” coming out of the darkness or sparkling through dimly lit spots on the stage.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Check out Waterwell.com's "The Courtroom"