Summer Robinson: The work you do merges art and social justice, and I’ve heard you reference something called the “Hidden Voices process.” Can you explain how that works?

Lynden Harris: The Hidden Voices process looks at three things by asking some very basic, very generative, open-ended questions: What are the outcomes we want to see? What are the outputs we’re going to create to accomplish those outcomes? And what’s the outreach required?

Every project has a steering circle of stakeholders, which includes those most impacted by the issue. For example, with Serving Life, the steering circle of stakeholders included six men of varying ages from diverse ethnic and geographical backgrounds, all of whom were living on death row.

For outcomes, we ask: “What changes would you want to see on a large scale, national or global?” Next we ask: “What changes would you like to see in your home communities?” And last: “What changes would you like to see in yourself by virtue of participating in this project?”

We look at all of those changes—we write them on a big board—and say, “Okay, that’s where we’re headed. So, what are the outputs? What do we need to create in order to accomplish those outcomes?”

The final questions, after looking at outcomes and outputs, are: “What’s the outreach? Who else needs to share? Who needs to be a part of this creative process? And who needs to listen?”

By the time we finish, we have a real map of the project. And it can grow and evolve, but we’ve got that map. We know where we’re headed, we know what we’re creating to get there, we know who we’re reaching to make those things possible.

By the time we finish, we have a real map of the project. And it can grow and evolve, but we’ve got that map.

Summer: How did you use the process to work with the men on death row?

Lynden: In 2013, a resident on death row read an article in the newspaper about our 2011 project None of the Above: Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline. He brought the article to the head psychologist at the prison who then emailed me about developing a project for the men. I told him we were too busy at the time, but if he could wait six months, we would come in and develop a program with the men.

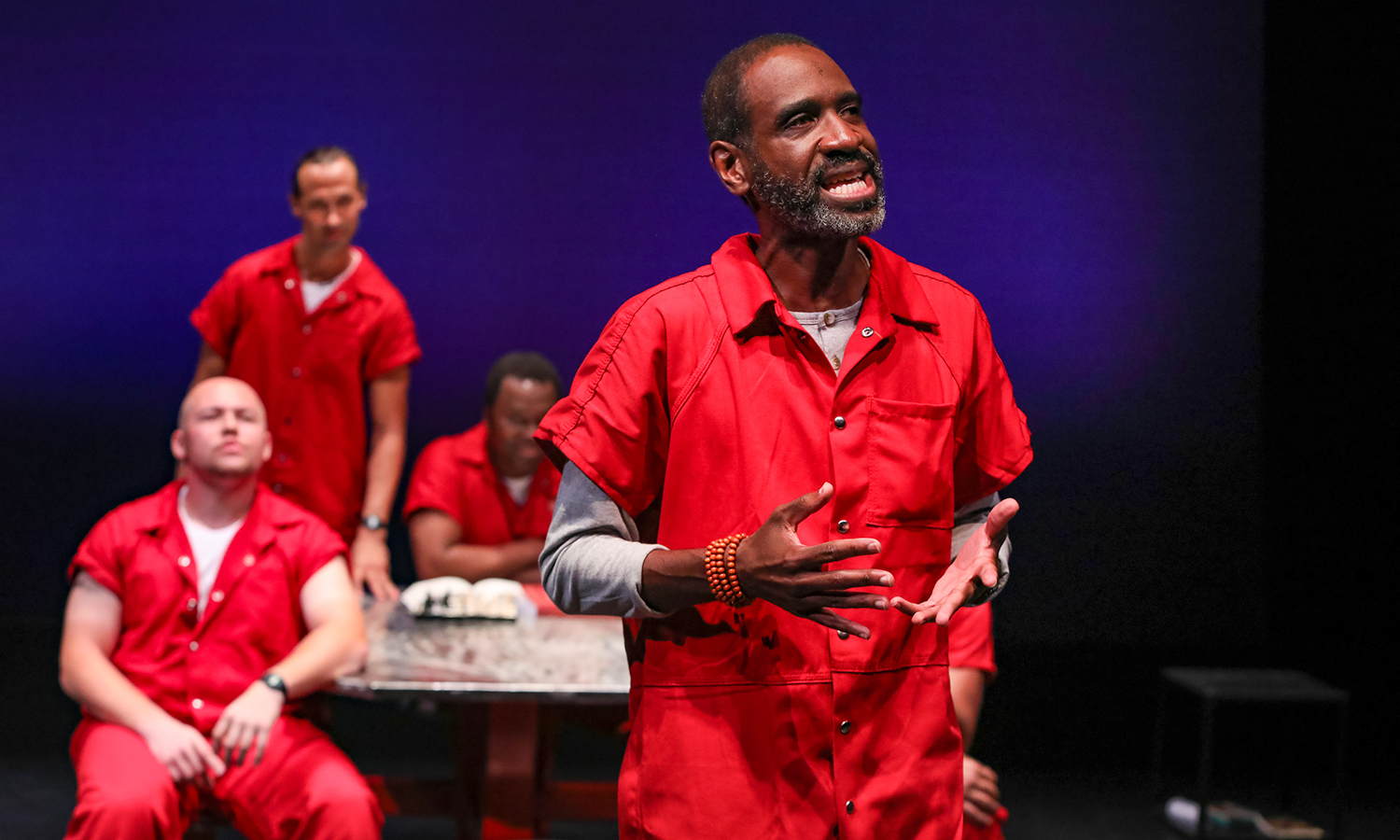

We used our same Hidden Voices process with a cohort of six men to develop Serving Life. After about a year of playing games, sharing stories, and writing, we co-created a play together that they performed for other residents of death row, corrections officers, mental health staff, and some administrators.

Summer: What was it like to have the men tell their stories?

Lynden: Extraordinary. Some men said that was the high point of their lives.

With Hidden Voices, we have a real vision of what’s possible, the kind of vision that many people don’t necessarily have for themselves. When we enter a project, we understand the potential. Often the participants go, “Yeah right, like that’s gonna happen.” But it can.

Kathy Williams, our associate director, who also directed the piece, tells this funny story about how we finished creating the script with the men, and only one person in the group had ever seen a play before. At the first rehearsal, the men were baffled by how the script was going to take shape with actual movement. Kathy started with some basic staging, but by the third time she came in, the guys were like, “We got this.” They started showing her how they planned on staging it. Turned out they had been getting together and rehearsing in their pods.

Ninety-nine out of a hundred times, listeners have never thought about who exactly we incarcerate but then there’s one person who says, “That’s my life.”

Counting dress rehearsals, the men were probably able to perform the show four times. They were so nervous! You could see sweat pouring down their faces. They were performing in the communal area, and you could see the prison cells behind and around the men. The fixed metal tables and seats became their set. It was surreal, very meta. At the end, many of the residents were weeping. And I honestly think every person there was on their feet applauding. It was remarkable.

The process led to the creation of a cycle of monologues based on the men’s stories, called Right Here, Right Now. We have several versions of different lengths that can be either performed by a few actors or read as a community reading in classrooms, churches, conferences, wherever. The stories are completely anonymous. Partly for the safety of the men and privacy of family members, but also because it’s easier to empathize and take it all in that way. If you know you’re hearing the story of a sixty-year-old African American man in New York City, you might say, “Oh, that’s not me.” But if you don’t have that context and you just hear this person telling the story of their childhood, it can go really deep.

Summer: What is something someone has said about the stories that will stick with you forever?

Lynden: I remember one woman who wept after participating in a reading that took place as part of a college course in a Justice Studies Department. She said, “I drive by a prison every day, and not once have I ever stopped to wonder who was inside.” It’s very intentional that we don’t think about those people.

Also, though, no matter where we go, somebody’s response is, “Thank you, my brother is in jail,” or, “That’s my cousin’s story.” Once somebody even said, “I have a family member on death row.” Those comments are always heartbreaking. Ninety-nine out of a hundred times, listeners have never thought about who exactly we incarcerate but then there’s one person who says, “That’s my life.”

Summer: It’s very telling and important that audience members are admitting that their lack of knowledge and concern has prevented them from considering the lives and experiences of people who are incarcerated. Often people will learn about an issue or hear a story but are still unwilling to understand their bias and actively work towards eliminating it.

I have to ask: How did you get started in this work? When did you realize you had this passion?

Lynden: I grew up in the South in the sixties and seventies, and storytelling was a really deep part of what people did. Theatre was one way to share the stories.

I’m a restorative justice circle keeper, which is the person responsible for creating and holding a talking circle. A talking circle is based on the ancient and sacred tradition of people coming together to celebrate, to build community, to address harm, and to restore harmony. We sit in a circle to underscore that all voices are of equal value and equally necessary for a community to be whole. It is an opportunity to connect from our hearts and across difference. The course I teach at Duke University, Stories for Social Change, uses talking circles.

Everyone in the class discusses their first experiences with a talking circle, and for a lot of us that was either sitting around a campfire or around a kitchen table sharing stories.

One of the outcomes the men wanted was to break the stereotype that people on death row are monsters. They also wanted to reach community members “with a voice and a vote.”

I remember the exact moment I became aware of story. I was eight or nine years old and at my grandmother’s house. We had just finished a big family dinner, and all the women sat down around the table for a few minutes before starting to clean up the meal they had spent hours preparing. The men, I believe, were all taking naps. I was about to go outside to play with my cousins, when suddenly I heard what these women were saying. Not just the drone of adult voices—I heard the words and the words were stories. So, I stayed.

Later, in the late nineties and early two thousands, there was a big conversation amongst theatres across the country about outreach and increasing diversity in our audiences. I was an artistic director at the time, and outreach pretty much meant: in February, trying to entice Black people to see the Black play you were going to do, and then, in March, getting women to come in to see the women’s play you were producing. Not that a desire to diversify audiences wasn’t a good impulse, but I kept wondering if we could flip that notion on its head and ask people in their own communities not what stories they wanted to see, but what stories they wanted to tell.

I began to go out and talk to people in the community. That’s how Hidden Voices started, as part of a larger theatre context. The idea took off, and we found ourselves scrambling to respond to all the requests coming our way.

Summer: Your most recent play, Count: Stories from America’s Death Row, tells the stories of six men living on death row, and takes place within a day. You created this piece for public audiences, right?

Lynden: Exactly. One of the outcomes the men wanted was to break the stereotype that people on death row are monsters. They also wanted to reach community members “with a voice and a vote.” We started working on a play based on stories from around the country—the characters are fictional, but all the stories are true. They touch on personal inheritances of violence, racism, mental illness, and surprising love. The hope is that audiences contemplate who is disposable, who counts, and what justice means.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The work that's being created is very inspiring and I wish more people would be as generous, compassionate, and caring as both Lynden and Summer. More people need to read this play and spread the awareness of this work.

Hi Paige. Thank you for your comment and kind words. We hope that you will be in touch. https://www.hiddenvoices.org/…

Lynden and Summer -- thank you for this beautiful conversation about important work and process. Very moving -- I'm just starting a new project with Prison Performing Arts in St. Louis and working in a similar process as yours, and wonder if I can contact you directly? Thanks so much, and thank you for your work.

Hi James. Thank you so much for your comment and the work that you are doing with Prison Performing Arts. We would love to further connect with you. Please contact us through our website and we will get back to you soon. https://www.hiddenvoices.org/…