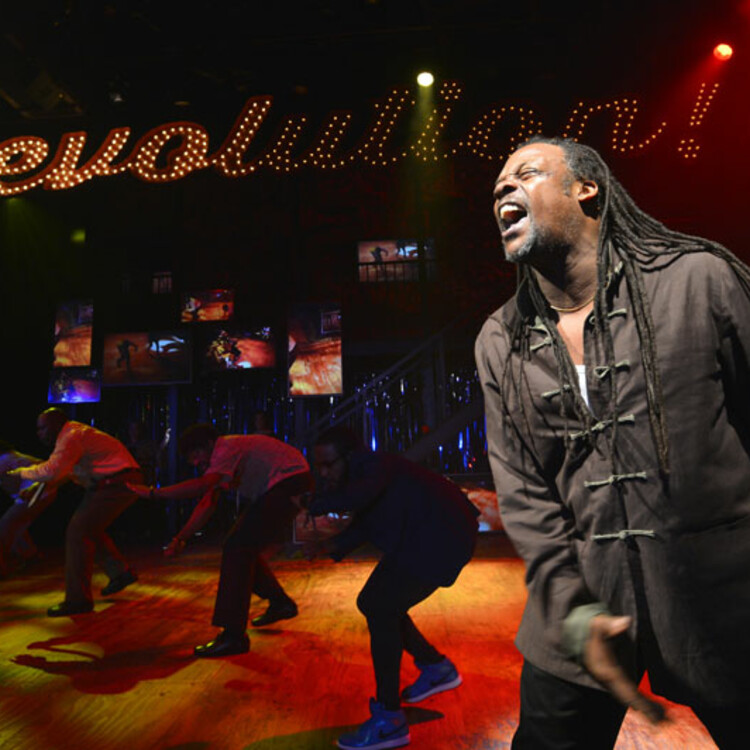

Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s Resident Ensemble Theatre: UNIVERSES

Jeffrey Mosser: Dear artists, welcome to another episode of the From the Ground Up podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. I’m your host, editor, and producer, Jeffrey Mosser, recording from the ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands, now known as Milwaukee, Wisconsin. These episodes are shared digitally to the internet. Let’s take a moment to consider the legacy of colonization embedded in the technology, structure, and ways of thinking that we use every day.

We are using equipment and high-speed internet not available in many Indigenous communities. Even the technologies that are central to much of the work we make leaves a significant carbon footprint, contributing to climate change that disproportionately affects Indigenous people worldwide. I invite you to join me in acknowledging all this, as well as our shared responsibility to make good of this time and for each of us to consider our roles and reconciliation, decolonization, and allyship.

Artists, y’all, I’m so excited for you to listen in on this one. It has a bit of history here for me. So, if you’ll please indulge me, I have to say that seeing the play Ameriville by UNIVERSES at Actors Theatre of Louisville at the Humana Festival of New American Plays was one of those life-changing moments for me. The show was current. It was political. It was collaborative. It was exciting. It was spectacle. It was genuine. It was one of the first ensemble-based theatre pieces that was sold as such in a large regional theatre that I had ever encountered.

It got me asking the questions that have led me to your ears today and as it turns out, I was in the same audience watching UNIVERSES as was Alison Carey, one of my guests today. Though, of course, we didn’t know each other yet, Alison was there on behalf of Oregon Shakespeare Festival and thus, at the start of a very special relationship. It also led to how UNIVERSES became the Resident Ensemble at OSF, where they created work only as they can.

I knew about this partnership long before I knew that the Center Theatre Group was creating the Roadmap to Innovation producing model. So for me, this producing process became my North Star in terms of producing opportunities for ensembles. Today’s interview is with three folks, Alison Carey, the former director of American Revolutions: The United States History Cycle at OSF, as well as Mildred Ruiz-Sapp and Steven Sapp of UNIVERSES.

And I have to say, it was pretty amazing to feel the exchange of energy between them. It was especially meaningful, as about a month prior to this recording, Alison had resigned from her position after fourteen years and had decided to leave Ashland, Oregon altogether. So, this conversation is as much informational as it is a reflection of the heartfelt relationship that went beyond a creative partnership. We use their work on UNIVERSES’ production of Party People as a case study for much of this conversation.

A few things to say before we get into it. First, you may hear a few internet connectivity issues and lagging throughout. I’ll do my best to address it in the audio transcription page on howlround.com and Steven mentions Roberta Uno, who is a director and the director of the arts in A Changing America at CalArts, as well as a Senior Program Officer at The Ford Foundation. This interview took place on September 27th, 2021, and all three of my interviewees Zoomed in from the ancestral lands of the Shasta and Takelma peoples, now known as Ashland, Oregon.

Mildred Ruiz-Sapp: The first time we met Alison Carey was during Ameriville, just—

Alison Carey: It was, and I stalked them in the lobby and offered them a commission.

Steven Sapp: Yes, she did.

Mildred: In Humana.

Steven: That is exactly how the story goes.

Alison: Best thing I ever did. Well, having kids was okay.

Jeffrey: That answers all my questions. Thanks, y'all. No. So can you describe who you make work for?

Steven: I’ll say this, and you can jump in. Obviously, when we started, we were performing for our community, people in the neighborhood and things of that nature. That's when we started. That’s what we were. Even when we were going, venturing, downtown in the Nuyorican Poets Café, the poetry, spoken word, hip-hop, jazz world, we were still pretty much performing in front of the choir. You know what I mean? People who got it, wanted to come get it, and receive it.

We were right there. And then, as our career progressed, we started ending up in places where they didn't know you. They didn’t stick from where we were from, but was what we were doing universal enough to reach folks from here, there, or whatever. And I think that was a big testament to the work, because we were able to get out of the neighborhood, get out of the open-mic scene that we were actually very well-known for. We could’ve stayed there and been, as we would say, ghetto celebs to the end, but we got these interesting offers with some interesting theatre practitioners.

And we studied it anyway, so it was just a natural progression. So, we create work for people who are like us and want to hear us and things of that nature, but also our voice has gotten bigger and the landscape of who we’re speaking to is bigger. But still in all, I still want some young Black kid from somewhere, or Puerto Rican girl or whatever, to come to a theatre where she wouldn’t expect to hear or see herself or people who she knows this big on the stage, which is the same stage she saw Shakespeare in two months previous. You know what I mean? If that happens, that's the most beautiful thing.

Mildred: I think that, tied to that, I would say we create work about all the people that we encounter, about ourselves, about our own families and friends and circles, but about other people that we encounter. We bring those people. They become part of our circle as we go around. It just all sticks to us, and we keep traveling through whatever this is. And it’s like, “Now, that person is part of me, and that person is part of me. And I’ve been impacted and influenced in one way or another by all of these different people who some are like-minded. Some are not.”

Even people who don’t agree with us are stuck to us and you bring them with you too, and you want to also lift their voice up in some kind of way. I think even, especially if we don’t agree with a person or a character, we try to bring that person’s humanity to the forefront and to just really tell stories that so many different people can find themselves in. That’s the way that we create work. It’s obviously us and for us to walk on stage, or create this kind of work, is a political act in and of itself.

So, our politics will always be entwined in whatever it is that we do, but we also try to bring other people’s politic in it as well because if not, that wouldn’t be a very interesting conversation. It would be a one-sided conversation, so we try to bring it all in.

Jeffrey: That’s fantastic. So, Alison, you talked about this a little bit earlier. So then, where along the way did you offer that commission that you spoke of to UNIVERSES?

Alison: I had known about UNIVERSES, of course, because everybody knows about UNIVERSES, but I had never seen their work. Because I had been in LA with Cornerstone Theater Company while, most of the time, you were in New York. So, Claudia Alick was like, “UNIVERSE is the bomb.” I was lucky enough to be able to go to Humana and see Ameriville, and it was that struck-by-lightning artistic experience. I walked outside and I called Bill Rauch, who was then artistic director of OSF. And he and I had started Cornerstone Theater Company together.

And I said, “I have to offer UNIVERSES a commission,” and he was like, “Okay.” So, I went back in, and it happened. And I do think in terms of just looking, my perception of who their work is for, I think everything you said is really smart and what I would say. And I think it has something to do with my time with Cornerstone, this notion of ensemble-ness. Your work also really speaks really strongly to people who want to be with other people, who want to make sense of the world with other people, because when you’re on stage, it’s not...

I mean, yes, you’re all these singular talents, but you’re also such a powerful collective devotion to humanness. And that just pours off the stage and fills audience members with that spirit of human connection. And I think that’s why it works so well everywhere. Even people who sometimes, I think, pretend they don’t, people really like to feel human connection and to see it and act it in front of them in such a powerful and pure and excellent way.

Jeffrey: I know. Everyone’s crying. This is great.

Alison: That’s the truth. Truth is powerful.

Jeffrey: Following that commission, what were the steps or what were the next moments before UNIVERSES was a resident ensemble at OSF?

Mildred: Well, that’s a long story.

Alison: I know.

Mildred: Well, I just got to say, so Alison appearing at the Humana Festival was one of the biggest doors opening in our life, right? So even though we had been already on a journey, on a trajectory and we were on a road, Alison brought us onto a completely different road. We’re actually still in Ashland, Oregon. We’re calling you from here, you know? So, it has actually changed the course of our life in so many ways, right? So just that moment where Steve talks about, “She was in the lobby and she held my hand,” and it was like that moment where you’re like, “Something is gonna...”

Something completely changed and you didn’t know it at the moment, but it did, so we came here. We were commissioned in 2009. We came here in 2012 to make Party People. When we left the Bronx, we were like, “Let’s pack up our stuff in this apartment that we’ve been in for so many years, and when we come back, we’ll just get a new place,” right? So, we packed up all of our stuff and we put it into storage. So, the goal was to come back home to do Party People, be free of rent and all of that, just pay a storage unit and just come to OSF, and then go home and figure the rest of life out.

And what happened here is that Alison Carey took such incredible care of us in so many ways, in more ways than one, from even getting a car. First, I’m borrowing her car, her and Ben’s car. So, our relationship was just beyond what the project was. She talks about we care for people and humanity and the spaces that people are in, but Alison is a caregiver. And she was like, “What’s happening? Where’s your son? How can I help? How can I support? You need a car,” da, da, da, da, so really making life work for us for a year the way that it had never worked for us before.

And then, having Quest here, even taking us around to two schools for our son, right? So, took us to see some options and said, “Are you sure you want this one? How about this one?” da, da, da. And ended up, our son went to school here. And then, by the end of the run, he’s looking out into a field and there’s lots of—

Steven: His second day of school.

Mildred:—lots of cows out there. You know what I’m saying? This is the second day of school or something for him, and he’s just like, “Can we stay?” And his playground in the Bronx, it was basically… I think there were maybe… I don’t know if there were—

Steven: It was the—

Mildred: one or two basketballs

Steven:— It was the teachers’—

Mildred: hoops.

Steven:—It was the teachers’ parking lot.

Mildred: The teachers’ parking lot. So, if there were cars that they had to maneuver around. They couldn’t play, because all the teachers had their cars in there and it was a concrete lot. That was their playground. And he was looking at a field for the cows and a track. He was like, “This is like the movies, Mom.” A Black and Puerto Rican kid from the Bronx now arriving at this movie set, and there are actors everywhere. And a world is going on.

So of course, we were like, “Let’s try to stay,” and we did. We found ourselves a little place to rent, which now we purchased. And then, after that, we were like, “I guess we’re here.” So, the next step was, “What do we do now?” And of course, Bill Rauch and Alison Carey and the whole family at OSF, they were like, “Well, what do you want to do? You want to be the ensemble?” We went, and we talked with Roberta Uno from The Ford Foundation. And we got some funding to help support us being the ensemble in residency at OSF and that journey began. That was the second step of the journey, and what would that mean, how we could create work, just be part of the whole ecosystem here.

Steven: I would say it like this for those people that are Star Wars fans. It’s like I was Luke Skywalker, and Alison was our Ben Kenobi and said, “Do you want to come to Tatooine?” It was like, “Tatooine?” And we took the offer, and we went to—

Mildred: That hero’s journey, you know?

Steven: Yeah. I mean, seriously, if you think about the hero’s journey, it’s always the offer. I always try to pay attention to those offers and it was a real genuine offer. It wasn’t about money, even someone bringing us on to be, and I’ll say it, the colored experience on a particular month or whatever it was. This was a legitimate conversation and I felt it. And I’ll say it. I’m not going to say what the number was, but even when she was like, “Well, this is the commission.” It was like...

Usually, I’ll look at it and be like, “Okay,” and now the negotiation begins. I looked at it. I was like, “And we have nothing else to really talk about. This is great.” It was cool. It was like, “Wow, she came for real. Great, let’s get to work.” And just that alone, and it may seem small, but those little things meant a lot and they registered in a deep way with us. So, when we were like, “Okay, we’re really going to share our lives with people,” I mean, we all do theatre.

So, you come in for rehearsal, then you go home, but it’s like, no, her kids and our kids know each other. We watching our kids grow up and see each other grow in this field together, but it took something like that, which may have seemed real innocent at that moment. But it was a legitimate connection, which was really nice.

Mildred: We’re New Yorkers, born and raised. Native New Yorkers, right? And the crazy thing is that it wasn’t so hard to see artists and artistic directors and be part of a theatre in New York other than Pregones. Pregones’ doors were always open. So aside from Pregones, the regional theatre scene and all of that was really hard for us to get into in New York. And New York Theatre Workshop obviously gave us our first shot and stuff like that, but it’s that one production shot, right?

And then, you have to wait, if ever they’ll do another work of yours. I mean, New York Theatre Workshop did two of our works, but it was such a big span of time that there was no way for us to really get our feet in there, but we started to notice that so many people were coming to OSF. We were seeing more people at OSF from throughout the field that we wouldn’t have seen if we had just stayed in the Bronx, and it was crazy. I don’t even know how that was happening, including Claudia Alick was bringing a lot of our poetry and performance scene up here.

So, we had our poetry and performance scene moving and flowing through here, plus you had OSF that was bringing the artistic directors that we never had even a reach to. Now, because it’s such a small village, this little town of ours here, you’re in town. You might as well have dinner with me, you know? And opposed to I’m in New York. There’s no way I’m going to have that much airtime from Oskar Eustis. It’s like, “Hey, Oskar, you and Evelyn, you want to have...?” you know. Or whoever, “Let’s have drink at Martino’s after a show,” or whatever.

It’s such a small container of a space, but everyone was coming. Now, all of a sudden, it was our world too and that became a new way of us being able to stay connected to the field as a whole. We actually could sit here and just welcome you and also have business conversations as we went. I think it was one of the greatest things that happened to us; plus, it is gorgeous here. It is gorgeous.

Jeffrey: I know. I’ve had the deer follow me home.

Mildred: Yeah.

Alison: Yeah, you got to watch out for them. The program we commissioned UNIVERSES through American Revolutions had the necessity requirement of talking about American history and trying to bring in as many different perspectives on what American history is. And so, one of the things when I saw Ameriville, I was like, “But they already did their show. Well, they’ll just have to do another one,” that spoke the meaning of the United States and the history of the United States so deeply.

And I think, in some ways, I can’t imagine that cycle without UNIVERSES, because they hold the universes of the United States within their hold. And I also think the generosity that they showed in being willing to come to Oregon—it’s a pain in the ass to get here and it’s not always the friendliest place for anybody. It’s certainly not always the friendliest place for people of color. It’s never the friendliest place for people of color. And I don’t mean to put my words and observations on your experience, Mildred and Steven, but without that generosity and spirit, being willing to come and share and create the work here, and to allow our audiences to see it, I don’t know see how a program like American Revolutions could work.

Because if it’s just the artists that have made their decades-long home in the regional theatre, then what kind of portrait of the United States would that create? It would be continuing the same false portrait and the same closed-door, closed-eye view of this country that we all live in together. Thank you and I was so glad you came because I love you so much. And I’m also so appreciative of your willingness to go on this ride out in the middle of fucking nowhere in Oregon.

Steven: So—

Mildred: Yeah, American Revolutions is a brilliant project, right? So first of all, we had been talking about America and everything we do, but this particular project and the people that it was bringing together, right? So first of all, it’s an honor for us to even be in the midst of all these other incredible playwrights, right? So, let’s start with Culture Clash. Culture Clash. I had heard about Culture Clash when I was in college. I tried to bring them out once upon a time.

And of course, I didn’t have the money to do it, but Culture Clash are icons to us. And they’re like legends, living legends, and now they’re friends. It was so amazing to just be like, “You’re invited to be part of this program, and we have Lynn Nottage. And we have Culture Clash and Robert Schenkkan and us.” And it was like—

Steven: And—

Mildred: Alright, you know?

Steven: It was a little surreal sometimes, walking into some of the room like, “Oh, there’s Lisa Kron. And, oh, Paula Vogel just said hi—”

Mildred: Oh my goodness.

Steven:—to us. It’s like, “Okay,” you know?

Mildred: What kind of world, right? What kind of amazing world Alison and Bill created for all these people to come together.

Steven: But again, like I said earlier, it’s about how people invite you to “the party,” and how they treat you when you’re in the party. So, because Alison invited us into those particular rooms with those particular folk at this particular time, and I was like, “Well, yeah, yeah, yeah, we deserve to be here.” You know? And then, they look at you and they’re like, “Oh my God, I saw your work.” And I’m like, “I saw your...” You know what I mean? And so, it really changed the perception about us in a lot of cases.

Mildred: Even to us.

Steven: How people talked to us and related to us, how we looked at ourselves like, “Well, all right, we’re here. We know we can do it.” And I’m happy that we were able to be our true authentic selves creating the art. What came out was what we felt, and it was supported. In a way, it was like, “Okay, people actually really hear us.” And then, we’ll see what lands in Oregon, which we were, in one sense, not afraid of, because we performed in so many different places. We had been to…

Mildred: Alaska.

Steven: We’ve been in Homer, Alaska, in a barn. We have performed in some places, so OSF was just another sort of like, “This is great. It’ll be amazing to see how this registers.” But to see the activists who came up, the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, who actually were able to come to Ashland to see the piece and for them to see their story told this big at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival meant a lot in ways that will never be documented or remembered. But we know for a fact, it touched them deeply, deeply, deeply.

Mildred: I mean, the great thing is Alison made the invitation, and then didn’t restrict us to any rules, you know? It—

Steven: Yeah.

Mildred: It was like, “So what do you want to write about? We’re going to give you a commission because of this piece you wrote on Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans,” right? That inspired me to say, “Oh yeah, definitely.” “And then, now that you have the commission, what do you want to write about?” So then, now it’s still up to us. It’s still in our ball court, and it’s like, “Okay, this is what we’re going to do. We’re going to write about the Black Panthers and the Young Lords in Ashland, Oregon.” You know what I’m saying? To have the permission and to have the resources to just do whatever you want, to dream the way that you have always been dreaming.

Jeffrey: No censorship, no restriction on content. Just, “What do you want to do? Go for it.”

Mildred: Yeah.

Steven: Yeah, it really was that and I will tell you this though. And that being said, you also have to surround yourself with the proper... The proper team has to be around us. Liesl Tommy was our director and was there in the trenches with us, crying in rehearsal rooms as we wrote things. There’s moments where literally the four of us in a room at four o’clock in the morning in the Black Swan Lab, and we have a ten o’clock rehearsal. And we’re—

Mildred: I think Carl was over there eavesdropping.

Steven: —and Carl is, and we’re writing the ending boo-hoo crying because of the things we were actually bringing up in the room, crying, and then having rehearsal at ten o’clock. Having that type of space to really create was really important. It was really important for us to feel like, “Okay, this is...” which allowed the best work to come out. And there’s amazing designers that are in the room. There are amazing crew here who are around working. So, all of this stuff, the amazing actors who we met and became friends with, not just actors in a play or colleagues. Friends and family with a lot of these folks.

So, all of that lends itself to what great collaborations can be. I think how people can receive what American Revolutions meant to OSF, beyond just what it meant to us, what it meant to OSF and what it meant to the theatre field in general, just looking at how Alison ran the program itself could be something that everyone should look at and track in terms of how you treat artists, and how artists’ work is produced and presented to the world.

Mildred: I still don’t think that the field realizes the importance of this project, in all honesty. A lot of times, the work that we create, people, they tie it to an institution, right? So now, especially nowadays when we’re talking about predominantly white institutions and what comes out of it, what doesn’t, whatever, whatever’s happening. And even we’ve been talking to Alison, “This thing needs to get published.” The amount of incredible work that has been created by these legendary people in this legendary time has to be solidified.

It has to live forever, and a lot of people will be like, “Oh, it’s a project.” And it’s like, “Y’all don’t even know. You don’t.” So, I’m just saying this now. One day, when somebody realizes, “Okay, we told you so,” and everybody’s just so about, “Oh, well, that’s OSF. Oh, well, that’s Berkeley Rep. Oh, well, that’s this or that’s that.” It belongs to that place. But what was created in this particular project, which is bigger than OSF in my opinion because it can even live beyond it. And it is something that I’ve never seen in this way, the way that each of those playwrights brought the stories of this country into some kinds of perspective.

I mean, Sweat is a prime example, right? It’s still running. People are still wanting to hear it. They haven’t even seen the entire canon that has been built under this umbrella, right? So, you have one or two that you’ve seen. You’ve seen LBJ. I don’t know what else, but you got to get it together, America, because this has been created. And actually, it is a floor plan, and I think other people can build on it because I just think it’s some of the most important work that we’ve been a part of. That we’ve been a part of this community that’s been creating this kind of work.

Alison: Really kind of you to say that and I just have to reinforce, OSF was a box, an empty theatre, right? And it only becomes meaningful when artists like you fill up that space.

Mildred: Alison, don’t make me—

Alison: It’s not the program.

Mildred: —cry.

Alison: It’s y’all.

Steven: Jeffrey, ask another question, ask another question.

Jeffrey: I know, I know. I’m sorry. I’m letting these moments roll, you know? I want to go back to the idea of The Ford Foundation. So you all, UNIVERSES, went to Ford Foundation and said, “Hey, here’s an idea,” and then OSF said, “That’s a good idea,” and then how that—

Mildred: We’ve always been producers.

Steven: Mildred said, “We’ve always been producers.” There was a couple things that we know, just in terms of as freelance artists, that you have to generate your own funds. It helps when you go to a theatre if you have something. As Tony Taccone would say, you got some skin in the game. So, we were already looking around for money to help support the project. We got —

Alison: Yeah, National Theater Project, NEFA?

Steven: Yes.

Mildred: Yes.

Steven: —National Theater Project grant, which gave us a nice bit of money, a nice budget to go around and interview Black Panthers and Young Lords, yeah. So, we had that money, and then we have a longstanding relationship with Roberta Uno, dating back to when she was at New WORLD Theater in Massachusetts. So, when she was at The Ford Foundation, and we’re talking about the things—

Mildred: 1990s.

Steven: —we’re doing. And she was like, “Well, how can I help with the project?” I think at that point, some of the funds were to get them to Ashland and Roberta was willing to put up money for that. Again, it’s a great collaboration with between the commissioning money, between us finding that money, and then OSF resources itself was able to pull all of it together.

Mildred: That’s important about this particular grant, bringing Black Panthers and Young Lords from across the country, right? So aside from the institution doing its own audience development work, we had a responsibility to our community and to our audiences to bring them in and to have them see themselves, so that’s really why we did that huge push to really welcome them into this space as well. And having lectures at SOU or just building community here as well was really important. And then, beyond that, we got a second Ford grant, which was the one that got us into the residency.

Alison: If I’m remembering correctly, I think Ford had actually resisted supporting OSF for a long time for all the reasons one might imagine, being such a profoundly white theatre, not solely but predominantly and very much the audiences are. I’m not sure it’s still true, but certainly then were actually older and whiter than most regional theatre audiences, which is really saying something. And so, it was a great gift that UNIVERSES gave to OSF to get us in conversation with The Ford Foundation and a couple of shout-outs now: Erin Washington, who made so many arrangements with the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, blessings upon her. Julie Dubiner, then associate director of American Revolutions, The Collins Foundation, and then The Mellon Foundation. And I think of Joe Haj at Playmakers who brought y’all out to do the workshop.

Steven: Oh yeah, that’s right.

Alison: There were some great key individuals, but there were also just all these institutions who stepped up and said, “How can I help?” like Playmakers repping North Carolina. It’s like, “Well, we have a space," and we’re like, "Cool, we’ll pay to get them there, and then you take care of them.” Again, I think that’s part of what UNIVERSES inspires in people like, “I want to be part of the party, and I want to help because I see how much your art helps the world. So how can I help you?”

Mildred: Oh, because we’ve always been on the road, we love to go to people’s houses, people’s theatres. For us to get on a plane, it’s like getting in a cab, “I’m coming,” you know? And because that’s what we’ve always done. So even though we’re here, or we’re in New York or wherever we are, we’ve never really been living anywhere in particular. We always say we live in United Airlines almost just to travel, but to have these relationships with all these different individuals, I don’t think we’ve ever been afraid of that.

And I think they’ve always been welcoming of us coming in, and they’ll give us a house. This particular thing, there were a lot of hands in the brewing of what became Party People. We had this ginormous task. We had this great responsibility to OSF, but we’ve given ourselves this ginormous responsibility to hold these stores together. And then, now you have all these people who are like, “All right.” Rolling up their sleeves and saying, “So how do we get it done? Let’s make it happen.”

Alison: I was just actually looking at the grant report for The Ford Foundation. The scale of what UNIVERSES did, some with our help but also the salons you had around the country, I mean, it just involved so many people. The Ford money brought in twenty-five, thirty Young Lords and Black Panthers. Part of the impact of the work is how UNIVERSES draws people to UNIVERSES, but also people come to UNIVERSES because UNIVERSES is this great ensemble. But again, it carries the spirit of ensemble out into everything it does. Black Panthers and Young Lords came, because also there were other Black Panthers and Young Lords coming. Everything they do makes the world larger.

Jeffrey: It’s amazing how you became a magnet. Do you think that funders are interested or excited in seeing ensemble-based work on regional theatre stages or on presenting houses stages?

Steven: Yes, they are excited. You have to connect the dots for them to go like, “Okay, yeah.” I’m not going to say we were the first to do it. Let’s say in a given year, we can do a regional theatre, a 50-seat house somewhere, a 150-seat house somewhere, an 800-seat house somewhere, a community, this is all in the span of a year and they’re all funded from different perspectives.

Mildred: A community center, a prison.

Steven: We would then make these connections. So, the work we would do, let’s say, in a small community center may have been the opening ten minutes of Ameriville, could’ve been graded over there. So then, you’ve connected Ameriville to the Humana Festival, to this community center that no one’s ever heard of, but there’s a link to it. So, we used our early days of open mics, and small performance spaces and things like that, to really fine-tune who we are as artists and as a company and raising funds.

So, when we arrived at OSF, we didn’t just kick back and be like, “OSF has this much money and within a week, we’re going to spend this much money on what it is we need.” And it was like, “Well, in order to meet these folks, we need to get out some money over here.” The funders got really excited when you make the connection for them to see it like, “Oh, this is how that works, great.” This is what they want theatres to be. They don’t want to give all the money for it. Be creative and find something, but if you got to have one hundred dollars and you can bring thirty five, forty dollars to the party, that helps greatly with how stuff is spent. So, to answer your question, yes.

Mildred: Sometimes, I don’t think that they see ensembles the way that they should, especially now in the era of devised work. So, we’re a different kind. We actually call ourselves an ensemble. It’s a different world than the devised world, in my opinion. We create work. It’s a different way to generate the work, but hopefully the ensemble... We’ve been part of the Network of Ensemble Theaters for ages, right? I think, if you look at the Network of Ensemble Theaters and you see how it’s still marginalized, that will give you an idea of how even the funders field and the field as a whole has still not embraced work, if the Network of Ensemble Theater is still in the margins and not leading even the conversations of devised work.

I was in that work of ensemble theatres, not leading the conversation about devised work. It’s when somebody else takes the work and your aesthetic and the way that you create things, and they want to make something else, but you’re still over there doing the thing. They robbed you a little bit of it so that then they create something else. So, when I see the Network of Ensemble Theaters become a huge like, “This is the core, the people who we’re having conversation with about ensemble work,” then I’ll tell you that people have really paid attention and not just fed off of it, and then gone off to do their own thing.

Alison: Well, first of all, who knows what’s going to happen as the pandemic continues to unfold and what happened to the field. And obviously, nobody has an answer, and it certainly scares me a lot that it would be easy not to support ensembles because their work costs more, right? And I think I suffered from this, just for starting out the American Revolutions program, is theatres have it in their head that they’re paying for a piece of art. And then, the mechanics of it, well, it doesn’t matter whether one person writes it or five people write it, right? What matters is that singular piece of art.

Now, of course, ensemble-based art is a different kind of art. They’re not interchangeable, but I think that might be a value and investment that goes away. One cannot think that people are completely irrational about making larger financial commitments at this point, right? And they should, because I still think that ensembles are so much the source of the good blood that’s going through theatrical veins, but it’s a scary time. And I would say the fascinating thing about having both Culture Clash share, and then UNIVERSES, and then the 1491s is you’re actually getting a little sub-company within your company.

And that is outside the obvious that presenting and producing are two very different things but producing a thing that has a producer within it is like, “Whoa!” next-level meta, “Whoa, shit, what am I doing?” And I think a lot of institutions find that really hard, because institutions have their way of doing things. And then, suddenly, there’s someone else there telling them what to do and telling them what to do, because they know how to do it, right?

And I appreciate you. Hats off to OSF in terms of how we supported you, but there were also times when you got stuck in the chainsaw of institutional theatre, and I think OSF has gotten better at caring for ensembles. The then-production model, which will not hold anymore in the new reality of wildfire smoke and global pandemic, there has to be a really intentional willingness and capacity to actually change up your processes, and not just change up your processes in a planned way. But there’s two different groups iterating at the same time, the ensemble and the institution, because everyone is always changing their practices.

And you all have to somehow get on the same train. Once you’re just like, “Fuck it, we’re doing a show,” then it becomes much easier, but there is institutions, especially as large as an institution as OSF was and still is, there’s so much behind you. There’s so many traditions and rules and unspoken rules and all of this stuff. So, it can be a very, very confusing place to know where to put your hand on what lever to get what done to make what change.

It’s also utterly awesome. What a gift to have another producing organization inside you, giving you new energy. I’m sorry. This is sounding a lot like the movie Alien, which is getting really weird, but it’s not. What a gift to institutional theatre to have another model of how to do things right there, giving you this gift of insight within your organization, and so much of it is about institutions and so many now are just hanging on by a thread anyway. But that makes me hope that people will be ever more open to ensembles, because I do think that there are lots of individuals and institutions in the field who are looking for new models, right?

Ensembles with their many challenges, there is that humanity at the core of it. And some sense of equity and sharing and respect that is a great model, not only for institutional theatre but for society. I hope our field has the wisdom to recognize and embrace the models that ensemble theatres offer to us every day.

Jeffrey: You mentioned chainsaws and I wonder if there’s an example of a chainsaw that UNIVERSES might’ve gotten caught up in.

Alison: Well, I—

Mildred: Give it to Alison. You pick one.

Jeffrey: One.

Alison: It’s that thing when you give birth, and it hurts like hell. And you instantly forget it so if you decide to have another child, you’re willing to do it, because why else would you possibly agree to go through that much pain? So, I do think I may have forgotten. A very simple example, and this is very OSF-specific, right? We’re in rotating rep. The props people aren’t always available to you, because Tuesday, they’re doing Party People props. And Wednesday, they’re doing All the Way props. And Thursday, they’re doing this other thing, right?

And so, a lot of the certain departments couldn’t be responsive. And no fault to the props. Love you, props. Just using you as an example of a department within the theatre. It wasn’t unwillingness. It was incapacity. It’s like, “Well, I have to do this thing for this other show.” I think that one of the challenges of working at OSF traditionally and I think the model’s going to be quite different moving forward, although I don’t know how, because I’m no longer affiliated with OSF, didn’t have the same devotion to the show that you were putting on, right? You had to always share and share the actors and share stage managers and share spaces with other shows.

Mildred: It’s funny, because we were a pretty big show in terms of size and in terms of props and in terms of every requirement. But we were also in the smaller space, the smallest space. And we were a little bit segregated from the other… The other two venues, the Bowmer and the Lizzie, Elizabethan, actors and everyone meet underneath. So, there’s a whole ecosystem happening in the underground, in the bowels of between those theatres. And the Thomas was completely removed, so we had to also learn, make our way over there and try to make sure that we were equitably taken care of, if I can be—

Alison: Totally.

Mildred: —trying to be correct about it. It’s like, “Well, yes, that’s happening over there in that show.” And matter of fact, we were playing against the Robert Schenkkan’s LBJ play, right? And that was in the Bowmar, so there were two American Revolutions plays happening in conversation, which was incredible. And one of the greatest moments, I just want to say, is when we actually did a crossover with our show into the LBJ space. So, we brought the Black Panther revolution into Lyndon Johnson’s office, you know?

And I remember we had our picket signs, and we were protesting. And I remember some of us stood up on LBJ’s beautiful desk, and just did an excerpt of Party People and stormed out right in the middle of their tech and, “Check this out. The revolution’s happening across the street while LBJ’s over here talking.” So, it was awesome to have this kind of pushback, and I think that the buzzsaw or the chainsaw that was happening there wasn’t the two plays.

It was maybe that OSF didn’t see the opportunity to capitalize on that conversation that was happening. It could’ve been so much bigger, because you had LBJ in the bigger house. And you had the crazy protestors and the revolutionaries in the smaller house. I think, if it would’ve been up to us, it would’ve been like they had to be the outside. The world had to know that these were happening. And I know, Alison, we pushed for it. We talked about this conversation, but I think that it could’ve been taken even further and that would’ve prepared us, better prepared us, for both LBJ going out and for Party People to go out, because then both of those pieces moved out into the world. LBJ, I think, made a beeline to Broadway and Party People went to Oakland, to Berkeley and to the Bay Area. I just feel there was an opportunity missed in how we could’ve really just had those two go.

Alison: I totally agree. I mean, OSF at the time, the marketing was very much the whole season, right? But these—

Mildred: Mm-hmm.

Alison: What was happening between these two shows. I mean, there’s always connections between shows, but the marketing department did not have the capacity for, at the time, the intention to pull out two shows and focus on them, as all shows deserve special attention, right?

Mildred: Of course, of course.

Alison: Part of OSF, you’re showing the experience. We did this amazing thing and Party People wasn’t the first time, but we still hadn’t gotten used to it, is we had three whole previews instead of two. And that’s some crazy-ass shit to have a show only have two previews, but it was a new play, so we got three. And this was a revolutionary behavior for OSF. Obviously, many other theatres had figured out that previews are good and many other artists. Our schedule of production had never depended on that to only support a new ensemble-based work with three previews before everything set. It’s fucked.

Jeffrey: Yeah, I want to go back for a hot second to, I think, Mildred, you said, about how ensembles are marginalized, creative groups. And I wonder, is it simply a matter of finances that ensembles are marginalized?

Steven: Yes. I mean, a lot of times, yeah, and I’ll say that only because, yes, obviously it’s a bigger budget. Now, on the flip side of that too, it’s also for mainstream, let’s say, regional theatre to bring you in the season, that you see ensembles sitting in someone’s seasons. You don’t see an individual playwright. And every now, maybe SITI Company, but SITI Company stayed more performance based. There’d be a few of us who are floating around, but a few of us who actually did land in someone’s seasons. It is a bigger thing.

Now, OSF, for example, had a resident company. So, we were able to make Party People bigger, because obviously we had the resources to make it bigger. But a lot of times, it does come down to, one, is it finances, what you’re paying for and then, B, trusting that this ensemble is going to bring in the type of work that would translate in a regional theatre setting. A lot of times, what ensemble companies would bring is something that’d be more performance based or slightly considered off to the side. So, I think, yes. It’s not always the case, but I think having sat through many budget meetings around it or talked with folks, it generally comes down to finance.

Alison: I think that’s certainly true. I also think there’s a little bit of ego involved among some gatekeepers of predominately white organizations especially who, of course, have so many more resources, but there is a certain sense of royalty that artistic directors can develop that ensembles, just by their mere existence, defy. Say the approach to world premieres in the nineties and 2000s. It was so much about old white guys slapping their dicks on the table and saying, “This is mine,” which is completely contrary to all of the ethos of anything good.

And you have artistic directors who can develop really intense relationships with individual playwrights and also direct plays. Whereas ensembles challenge the energy of the singular leader in a really, really healthy way, but I think a lot of people just don’t want to be bothered because I’ve got my kingdom, and I’ve got my acolytes. And I know I’m being really reductive, and I don’t mean to be cruel or lying. But I do think there are elements of that, that you see. And then, the other theatre isn’t doing it, so you’re not do... I mean, the whole—

Mildred: Well, there is a lot of truth to that, just speaking from our own experience. For instance, Steve and I pretty much would go to all these meetings, or sometimes we would want to bring another member of UNIVERSES or two. And this is not just OSF. This is theatres throughout the country, right? They’d be like, “Well, I don’t know. Can we talk to one of you?” They just couldn’t handle more than one person in the room, talking about the business of UNIVERSES and where we would have conversations in the room with each other, and we knew what we were going to do.

We know what everybody’s getting paid. There’s no secret, whereas you go into these institutions, and you’re not even allowed to talk about, with other actors or with other playwrights, what you’re making. There’s this taboo and this secrecy and this level of hierarchy that you have to push up again, you know? They’ll talk to Steve, because they can only speak with one person at a time, but we had to learn this way of speaking as one voice. Yes, we’re married, and that happens automatically. Thank goodness, that helps, but when we’re in a room with an artistic director, we pay attention to the way that their eyes are fluttering or their body language. Or they’re about to throw up. I don’t know.

They can’t handle too much information coming at them from two different places, so I’ll stay back. There’s this ebb and flow, and then Steve will go. And we orchestrate the way that we have conversations with these leaders because they can only hear things, some of them, from one person.

Steven: Something we developed really nicely with Bill Rauch; it was very organic. And I’m not sure if Bill does this with everyone, but with us, it was every time we would go into his office, the first ten, fifteen minutes of our conversation was about family. It had nothing to do with art, very intensely for ten, fifteen minutes.

Mildred: And that would bring down—

Steven: And it would just be like, “Okay, we did that.” And then, we would handle our business and it kept things sane, I think, almost and just feeling like human beings. Bill was comfortable having a group conversation. Not many people are, and so it is about introducing it to some institutions in drips and drabs where, let’s say, I may go first. I always try to make sure, eventually, the artistic director’s going to meet everybody at one time and is going to have to deal with whoever is on the road.

They’re going to have to deal with the entire company and the different personalities, that we do move as one while we’re on the road, which is how theatres can and should move and should operate. So, is it financial? Yes. Is it a model that they’re used to having function in a specific way and ensembles were not part of that equation? We were not in the bigger sense of the word. So, for us, in a very weird way, we carved our own niche and fine-tuned ourselves in terms of our voice and our aesthetic and things of that nature.

So, when we got offered to go to Tatooine, we were able to step into it fully and be completely comfortable with who we were as a company and everything else like that to be able to accept an offer like that and also flourish with that offer.

Mildred: There’s one thing I want to say that I learned from the acting company here at OSF and this is separate from being a playwright, but one day, I was on stage with these incredible artists, right? And it wasn’t one of our plays. It was an Elizabethan and Shakespeare play, and we’re all around each other. We’re having some crazy conversation, and somebody said, “I went to Yale.” And somebody else went to Harvard and somebody else went here. We went to Bard, so we were all throwing our colleges around like a hot potato, because that’s what you do, right?

You have to justify why you spent so much money, and you’re still in debt. One person in the acting company stepped up and said, “Well, I didn’t go to college. I only graduated high school.” And it put all of it into perspective and this particular person was a person that I was emulating, and I was foaming at the mouth trying to learn everything that that person was doing. And it’s like slap in the face and we were like, “What?” And it’s this idea that we’re better than someone else, because we’ve had an access or an opportunity to something.

I’m bringing that up to say, in American theatre, people walk around with these chips on their shoulders and, “Well, we’re artmakers and we know how to do this, and we produced this many shows. And we’ve done this, and we have this much money.” And like Alison said, there are so many dicks on the table. You know what I’m saying? You’re like, “Okay.” But the fact of the matter is that, a lot of the times, the artist, the simple artist or the person who’s coming up with a creative idea has the power in the room.

And that person also knows how to produce, and that person also has been in this situation. They may have more experience than you in a particular area of theatre or performance or poetry. So, the idea that American theatre continues to just elevate itself and say, “Well, this is how it’s done, and this is how. And then, I have these line producers and this, that, and the other.” And then, an ensemble of people come in and/or an individual playwright, who has not been part of these big institutions. And it’s like, “And that’s all well and good, and I still want my play to be like this. And the reason why you have a job is because of my play, right, because I wrote this thing.”

Alison: Hear, hear, yeah.

Mildred: Okay? So, I just want to put that back into perspective and, I don’t know. Somebody might get mad at me for saying it, but the fact of the matter is that theatre has forgotten why it is here, why it does what it does, and how we can do what it does, right? So, you are here to make theatre. The people who create the theatre are the artists, so I think that little pyramid has to be tipped on its head. There is definitely a dysfunction in the way that we perceive each other, even in a room, even an artistic director.

I might feel that they’re more in power than they even feel that they are. So, I think that people need to start deconstructing a lot of the way that they move through all of this and involve the artist more. I think that American theatre has stopped involving the actual artmakers in a lot of what it’s doing, even in the leadership of some of these institutions, just to go into all of it. We’re the artists that are making the work and how are they being empowered. And that means that we would have to step aside sometimes too as producers and let the artists, even within UNIVERSES, like, "What do you want to say? What is your voice?"

So, Steven and Mildred got to calm down for a second, "UNIVERSES, what do we want to create? What are you dreaming of? What do you want to write about? What do you want to talk about? How do we want to move through life?" It’s something that we’ve learned to do with our ensemble, and hopefully other people can do it with their theatres.

Alison: Hear, hear. There’s so much that the field takes for granted. You go into the average regional theatre rehearsal room. It’s a fucking dictatorship, man. There is not a democratic or equitable principle anywhere in the practice, and it’s insane. You don’t want a society like that. Why are you doing a workroom like that? And again, that’s, I think, a way an ensemble challenges that fascistic tradition.

Jeffrey: Organizations that have new-play development on their docket already seem to be ready to grab onto ensembles in some way, or at least bring them in or think about them or talk about them, right? There’s risk in having ensembles. There’s a risk in having that sort of artist in your room, and there’s a risk to having someone who might challenge this system of making. And then it’s also like, "Do they speak to your community?" So, I find that really fascinating and that’s why I started the talk saying, "Who do you make work for?" because I’m so curious that, from what I’ve seen, I love UNIVERSES, because you lay it on there and we all go, "Oh yeah, if only I had these perspectives in my lives every day." But I think it’s understanding that, "Oh, we need to have these perspectives."

And that’s a risk for the ye olde regional theatre to pull up and say, "Yeah, I want to invite that risk into my theatre." But yes, also to what we were all saying, that I agree that there is also a financial component to that. Because if my community doesn’t jam with this, then my bottom line, my box office gets upset. My marketing department gets upset, and then my board of directors gets upset at the artistic director for making such a rash decision, right? I don’t know. I guess what I’m saying is, thanks to everyone, all those organizations that take the risk.

Steven: It’s risky. I think what we’re also talking about, too, is just the change in the lens of power in institutions and who "gatekeepers" and what does that mean, and who are you involving in a power position in these organizations and how you deal with community. Some theatres can be in an area where they don’t have to deal with the community at all, because they don’t want answers coming from subscribers. So, the community around them, they really don’t have to deal with them at all.

And maybe it’d be a special show that pops up and it’d be a special flyer, and they’ll go to the barber shops and the hairdressers, or wherever they need to go. Or synagogues if it’s something. It’s very specific, but for the most part, it sits the way it sits. And because of the pandemic, because of the civil unrest in the country itself, if you don’t deal with your community, your community’s going to deal with you. I used to say this at different places, and I do mean it. And it’s a little bit scarier now.

If there’s civil unrest going on somewhere in the country, let’s say at a city, and they’re going down and destroying buildings that are government buildings or whatever. And they tore down the police precinct, and then they arrive to your theatre. Do they burn it down or do they pass it by? And if they burn it, that says a lot. If you has something that means something to that community, they will pass it by. They will protect it.

Mildred: They’ll protect it.

Steven: If it’s not, they will burn it down. And obviously, you saying hypothetically, but if you have to think hypothetically, if this community rolls up—

Mildred: Or they will stop somebody from doing something.

Steven: —and they’re coming down and they get to your theatre, what do they do to it? And how they interact with it should be what everyone’s thinking in terms of, again, we are a new society. We’re different, the rules. A lot of things have been blown open. How are these same institutions going to deal with the new playing field they’re dealing with now? You can’t run it the same way. You can’t have the same people running it that way. You need different, just as smart, people to come into a little room with your traditional theatre people who do X, Y, and Z so the theatre will feel comfortable. And they don’t feel like they have to change everything.

Mildred: And they want to all feel a part.

Steven: But you need a new, fresh approach in rooms, in how institutions interact with community. Our whole career has been, everywhere we go, we try to interact with the community. And we almost force the institution to have to be bothered with the community that we know. It’s a special event or something like that. If they bring a group of kids for a show, we make sure we stay and talk to those kids and take pictures with those kids and interact with those kids in ways that the theatre would be like...

If they asked us, artists, to do it, the artists would say no. But we do it on our own, just because we know, for those kids that come, this is their experience, but does the theatre do it after we leave? No. You know what I mean? How do you keep that practice going? So, I think it’s that. It is leadership. It is about challenging structure, and sometimes, most of the time, these theatre institutions in their structure are only going to listen to people who know how to talk that language, to get that far up in power.

If you can’t speak that language, then you will not get that far in that hierarchy. So, it’s about learning all this stuff, all these conversations, and all these different ways in different communities and places that you function as an artist. We’ve been with designers. We’ve been with community. We’ve been with artistic directors. We’ve been with so many different type of people that know how to talk in all those rooms. This is what you have to bring to an organization now in the year 2021 that’s going to interact with the theatre community, the community, and the emergence of social media. How do you deal with that? Your theatre is not the hot place to go on a Friday night anymore, you know? There are other things to do, so what are you going to—

Alison: Unless UNIVERSES move there.

Steven: —do to keep that energy going?

Alison: Jeffrey, you were talking about risk. Certainly, there is emotional risk sometimes for some institutions in having an institution there. Number one, in terms of, well, if the community doesn’t groove with the ensemble, the financial hit. I think those financial risks are largely overblown in the minds of producers. And I say that partially because I’m 150 years old and watching what American theatre did to itself for decades. There was this rule, absolute rule, that people wouldn’t go to new work, every theatre.

And many theatres still say it and it’s nonsense. And what the regional theatre did to itself was, over decades, just keep making itself smaller and smaller and smaller. And yes, there are some people who appreciate familiarity of a story they know. But at some point, it just becomes a big, fat bore, and people don’t come to the theatre anymore. It’s like, "Thank you, Arthur Miller, but I know, yes, attention must be paid," right? I got that.

And so, it was astonishing to watch people only say... And thank Mellon for really investing in theatre supporting new work, but the capacity to create new work was already there, right? It’s just theatres didn’t believe that it would actually work, which was nonsense, right? And so, they do the same show over again. And then, even then when they’re like, "Well, maybe we should try a new play," it’d be like, "but it can only have two cast members," right?

Well, and unsurprisingly, some two-handers can be great, but that does not necessarily embrace the full dynamic possibility of human beings together on the stage, right? It doesn’t give the audience the variety that they want. And again, so you make yourself smaller and smaller and smaller because of your lack of imagination about what is possible from a producorial and artistic perspective. And I think we’re digging ourselves out of these holes, but to everything Steven just said, as a field, we have to accelerate our embrace of the energy aesthetics and the ethics of things like ensemble-based and community-based work. Or it’s just going to die.

And frankly, it deserves it, right? What’s the fucking point? The world is fucking burning down. You don’t think we can try something new for a while and really invest, and go big or go home? And what’s the worst thing that happens? Your theatre folds, right? Wouldn’t you rather die trying? You know what I mean? And I know the boards, that’s not their job, but it should be to be like, "Oh well, you suck. Time to close." But anyway, that’s a whole different conversation. I think frequently we look at the wrong metrics to assess risk. That was my forty-five-minute way of making that very simple observation.

Mildred: It’s funny, because to bring an ensemble of four or five people, you look at that as like, "Oh man, there’s just so many bodies and it’s going to cost so much money. And I have to get housing, and I got to get travel for those people," five people in an ensemble. Now, compare that to the thing that they end up actually doing. They’ll devise a work instead, right? So now, they’ll pay this artistic director to sit and collaborate. And you have a dramaturg, and you have all these people, who you still have to fly in, and you also have to house.

And now, that director’s fee is phenomenally larger than what the ensemble’s entire fee might have been. So yeah, at the end of the day, even though they feel like they saved money because they didn’t have as many bodies in the room, they actually spent more money. Because now you had a person who probably has never even devised or created ensemble-like work in this space. And it’s taking a lot longer for the work to be developed and their fee is a lot larger, and we’ve actually seen this, you know?

This is truth where our fee is smaller, but our body is bigger, so it is more threatening as a... I can’t even wrap my head around that, but I’ll pay somebody else a larger fee. And it’ll just be one person or two people, but you still ended up paying more money. It’s one of those situations where people really have to evaluate, not only the money you’re spending or the size of the groups but also the value in what kind of work is being created, who is creating that work, the artistry.

Everybody loves to brag about the craft, the craft of theatre. We all have a craft. We’ve all studied. We’ve all developed. We’ve all built, right? And the fact of the matter is that a young person today can come out of around the corner and trump us all with all of our craft, because they have the great idea. And they have the great story, and they’re amazing. And that is simple as that. I went to high school, and you all went here. And I’m still better.

We need to just be careful in trying to see things like this, you know? It’s like, "Oh, it’s so big, and it’s so intangible and so impossible. It’s so difficult," and just be like, "How do we make it get done?" And that was one of the things that Alison did when we came in through American Revolutions. I think that why we gravitated to Alison the way that we did. It was like, "Okay, so let’s get it done," you know? And it wasn’t anybody feeding us or forming us or molding us or pushing us.

We chose our own designers, our own director. We chose everything ourselves. It’s not like OSF even pushed a director on us. We went and saw Lisa when she directed Ruined here, and we left that place crying. We were like, "Oh my God, who directed Ruined?" And we knew Lisa from way back in the days when she was a fellow at New York Theatre Workshop, right? And here she is directing Ruined and we’re sobbing. And we were like, "She has to do Party People."

And Alison’s like, "Okay, great. Let’s do it. What do you want? What do you do?" So that’s the reason why we have stayed around Alison so long is like, "Let’s play," because you know why? Here’s the truth. The truth is that Alison is from Cornerstone, and Cornerstone carries that same ensemble energy, that creative energy, that community. So, because we’re like-minded and I think that that’s what theatre need more of, people that have been on the ground.

You may see us now. You may be like, “Oh yeah, they’re institutional folks,” but the fact of the matter is that Alison... Look at Alison before OSF. Look at Mildred and Steve before OSF. Those are our roots. That’s our DNA. That’s how we move through life. That’s how we move through the world. And whether it’s at OSF or somewhere else, it doesn’t matter. I could go back home. We could be anywhere on the planet. We’ve been across the pond. We’ve been everywhere and it’s always been the same.

We’re bringing that same DNA from the community and the people that we came from, and we move forward with it regardless of where we are. So, it’s not like this is going to end and that’s how we all move through life. And that’s why we stayed, because we knew that there were people running it that would just be like, "Oh yeah? So, let’s do it. Let’s go. What do you have? Let’s try it," and to be free to fail, to be free like, "Well, maybe it won’t work, but why not? Let’s try it," you know? So that’s fun. That’s how we like to exist.

Jeffrey: All this being said, if institutional views may be changing or if they need to change in order for ensembles to be made a part or invited in as a part of that risk or as a part of that connection to their community, where do you think that ensemble work is going right now?

Steven: I think I’ve seen more ensembles come together now, much more people thinking along those lines, so that’s exciting. And I’m not saying it’s just because of us, but I mean there’s a few ensembles that have broken through regional theatres and perform a lot as ensembles in ways that did not exist ten years ago.

Mildred: Yeah, Culture Clash, SITI Theatre.

Steven: Culture Clash, SITI, you know? There’s been a few companies that have broken through, whatever that means, to that level. So, in that regard, yes. And I think, because of that, theatres are getting a little bit more curious in terms of, “Well, how does this work?” Once you get to a certain point in terms of your work and people want to work with you, then they have to have a conversation with you on how to actually do it. So, I think there’s been more of those conversations going on like, “So how does this work?”

If you look at Campo Santo, which is in the Bay, and Sean San Jose who now runs Magic Theatre is a beautiful example of someone who comes out of our world of ensemble-building and community and activism. And now he’s running the Magic Theatre. So, it’s going to be really curious to see how does that reverberate in the field, and he’s an artist. Is there any other regional theatres that are willing to take a chance or looking at any artist to run their institutions, not just come and be around, not just come do a show, not even necessarily just be the ensemble in residence, but really come and have some semblance of power to really run an institution? And obviously, you have to pick those who know how to do it—

Mildred: Or shape the program or

Steven:—really to be there. And I mean, everyone else, you’ll see a singer who has a record label and could run that or run this business or that business. So why can’t theatre artists who understand theatre in the same way and a different way run an institution? And I think that would also impact the ensemble world as well if ensembles are really at the table in terms of having a voice and having some power.

Alison: The fact that this huge generational turnover is happening in so many institutional theatres, combined with the pandemic, I mean the possibility of a new future exists. And we’ll just see if collectively we can meet the moment because I also think there’s so many moments in the process of creating theatre that are just deeply fucking lonely in traditional institutional theatres, people with singular titles. In theory, theatres are so collaborative. The process of making art is so collaborative and theatre is.

It’s also extraordinarily hierarchical and in that hierarchy lies so much of the source of the loneliness, and the pandemic took this loneliness. Not only did we lose so many people and are still losing so many people, but it just ripped the skin off of any process that made you lonely and no more, right? I’m not going to engage in those things that make me feel lonely and less human, and theatre is so incredibly human at its finest. And if we can, following the model of ensemble theatres and beautiful artists like UNIVERSES, if we can remember what it’s like to have the skin ripped off you, and be cared for by our art form, and to care for our society and its people through this art form, then we will be making the world better on all these different levels at the same time. My hope is that ensembles continue to thrive and that all theatres more eagerly both embrace and support the work but embrace and support the ethos of deeply equitable collaboration.

Jeffrey: Anything else that I didn’t give y’all a chance to say in this past hour and a half?

Steven: It’s still beautiful, and I mean this sincerely, to be on a Zoom call like this with Alison and yourself in terms of the stretch of the work. How we move around the world as human beings on a planet and who we connect with and just happy to be able to be lucky and honored to share space with, to create work with, is priceless. And you don’t get that everywhere. And I’m glad that we were able to pay attention. I’m glad that we were able to connect with folks who were ready to connect and ready to really blow open, because even what OSF was doing at the time, many theatres weren’t even doing that or producing the same work.

It’s funny and I don’t mean this as a slight to anybody, but I was talking to Richard Montoya very early in the process and he said to me, “Now, you know before Bill and Alison, OSF would’ve never produced Culture Clash or UNIVERSES.” And I was like, “Yeah, I can dig that.” Now, did I know Libby? No.

Mildred: There was a shift.

Steven: There was a definite shift in the perception of what the possibilities were, and how a company like Culture Clash and ourselves felt like... Well, we didn’t really feel like we would’ve fit that mold. But this mold that is here now with Bill and Alison and Chris Acebo, we feel that here and that OSF family. We feel that. So to be having this conversation many years later, our kids are all out in the world.

Mildred: There’s another shift.

Steven: You know?

Mildred: This is another shift, yeah.

Steven: But to still be connected that way as people on a planet, as colleagues, as friends, as family, that’s a beautiful thing. When I talk to students and things like that, at the end of the class, I’m like, “Do you see what you created in this time?” And I tell them, “You are now part of an artistic family. Whether you know it or not, you have now joined the club, the party. You’re part of it now. How much you stay connected with it or how much you want to interact with it is up to you. But when you make that commitment to it, you’re now part of it.” So, when you find like-minded individuals in heart, body, and soul, it’s a beautiful thing. So, I try to recognize that because it doesn’t happen all the time.

Alison: That’s very kind. You’re very kind and I love you both very much, and I want to—

Mildred: Yeah, we’re telling the truth.

Alison: I do want to talk about one thing, which is the hands across time of the movements of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. Party People always calls to the moment that we’re in, because it is about movements, about collective action. And there’s nothing that can be accomplished in society without collective action. I have this whole theory, which I won’t talk about now, but one of the challenges of traditional theatre is you have this singular individual on a journey, right?

And it’s so unusual and one of the astounding things about Party People, it is a portrait of movement, and it’s a portrait of sometimes troubling and flawed and all the things, collective effort toward making the world better. And we need more of that, right? Because when we see movement on stage, then it gives us a map to make them for ourselves. So, you get this double-meaning of not only the collective of UNIVERSES portraying the collective action of political movements is wonderful and life-changing if we can learn from it. And so, I hope the show just is produced and produced and produced and produced, because there will always be that call for collective action, and we all need maps on how to do it.

Steven: Yes.

Mildred: I think that, as we all also continue to move along and become two hundred years old, I—

Alison: Still older than you, Mildred.

Mildred:—I think that it’s important and this is what we focused on in Party People is trying to bring out the humanity, just show that these were just regular people, you know? The thing is that we put everything, everybody, on a pedestal, and this was just somebody’s little kid. I would say whenever I see somebody, especially a houseless person on the street, I’m like, “That’s somebody’s baby. Somebody held that baby once.” You know what I’m saying?

If you stop looking at the circumstance or you put yourself away from the discomfort, or you try to put yourself higher than the other and you just look at it as, at one point, we were all just in diapers and held and hopefully loved, then that gives us a different perspective, you know? All of us, we’ve all moved through life trying to make our way. The Panthers, they were all somebody’s baby. You look at the Panther. You’re like, “Oh my God, it’s a Black Panther. It’s a Young Lord.”

Look at the presidents nowadays, right? So everybody who is the president, one time, you were just a baby in diapers, just like me. And I think that that’s how we try to tell that story of Party People, and sometimes you make mistakes and sometimes you fell. And then you got up, and then you learned something new. And then you built a little Lego set. And then, now all of a sudden, you’re holding a picket sign, but life has taken you through this journey.

And I think that that’s the beauty of Party People and Party People, even though we created it, it created itself because of everybody who was a part of it and all the stories we were trying to tell and how we were layering them in and out of each other. I mean, I think that that’s the way that we love creating. That’s the thing that keeps us alive when we can look back, whatever is on stage. If I was watching it on stage and I didn’t write it, I could feel that I need to learn something from it, you know?

If you create something that you, yourself, can learn from, then I think you will continue to do it, which is probably why we’ve stayed in this, this long. And sometimes, we’ve had money and sometimes we haven’t. Just like every other artist in America, sometimes you have a gig and sometimes you don’t. And you still got to pay that rent, but the idea is that I can’t stop doing this, because I have a lot of learning to do still. And I can only learn through making art, if that makes any sense.

Culture Clash, I look at them all the time. You look at Herbert, his paintings. You’re like, “They’re learning,” continuous learning and moving and reshaping and remolding, and especially ensembles are always learning with each other. You learn from each other. We get into arguments. It’s part of the joy that we get from doing this, regardless of the pandemic, and we might bring new tools with us that we were able to learn in the Great Pause.

How do we move forward with it and through it? So yeah, American theatre, thank you for welcoming us and inviting us, and now let’s figure out what this means moving forward. Because if I can’t be the same person I was before this pandemic, there is no way I’m going to allow you to be the same person you were before the pandemic.

Jeffrey: Michael Rohd said you’d be a fun interview and—

Mildred: Michael!

Jeffrey: He was right, and I thank you all so, so, so very much for your time.

Mildred: Yay.

Steven: Thank you.

Alison: Thank you.

Mildred: Thank you.

Steven: Thank you.

Jeffrey: Much appreciated.

Mildred: Bye.

Alison: See you Wednesday. But I’m going to call you before then, so we can make a plan.

Mildred: Okay.

Steven: Okay.

Mildred: Love you, Alison.

Alison: Love you too.

Mildred: Bye.

Alison: Bye.

Mildred: Bye.

Jeffrey: That story about Mildred and Steven’s kiddos asking, “Can we stay?” That’s it. That’s my heart. That’s the social part of this podcast’s mission, right? How can we be socially sustainable in this world where nothing is consistent about theatre? And the commission being an amount that was meaningful for them, that’s what it’s all about. We’re humans, y’all. Let’s treat each other as such. Mildred’s idea about how this work needs to get shared, particularly that of the American Revolutions project at OSF is exactly how I feel about ensemble theatre work and how it needs to be shared.

The work we do in the theatre should belong to everyone, not just one region. We need to share the cultures, the expressions, the ideas. And sometimes, it’ll hit an audience in the right spot, but even if it doesn’t, it will still make an impression. As Alison said, producing a thing that has a producer in it is next-level thinking. It’s allowing an authority to take over a process. As she says, there has to be a really intentional willingness and capacity to actually change up your processes.

There are two groups iterating and at the same time, and that’s really tricky to navigate and I love how Alison stated that the financial risk for producers is overblown. Thinking back on it, producing an ensemble theatre at a regional theatre that has capacity is not unlike producing a new play development process. The audience is going to take a risk in coming to see it and the theatre has trust in the ensemble to make that. Your audiences want to take that risk and make that jump with you, and your adventurous groups who are ready to see it will be ready for it, which I really love.