With sharp attention to ongoing and embedded systemic and structural Indigenous erasure, racism and colonial and anti-Black representation within institutions, we must transform and change institutional systems and governance.

—Decolonial Action Coalition

In the United States, we have repeatedly seen that when new Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) faces are present in leadership, the ingrained structure of institutions present unique obstacles that impede their success. This is true not only in the arts, but across many industries. It is crucial to seek out new types of leadership that are not anchored in the patriarchal, hierarchical, and colonial structures that have brought us to where we are now. We have the opportunity to embrace the regenerative and kinship-based approaches to leadership that have existed for tens of thousands of years, begun when Indigenous peoples first stewarded these lands and were joined by Africans who cared for the environment, the community, and each other. Maya Angelou stated,

"I have tremendous respect for the past. If you do not know where you came from, you cannot predict where you will go. I revere the past, but I am an individual of the present. I’m here, and I do my best to be completely centered in this location before moving on to the next."

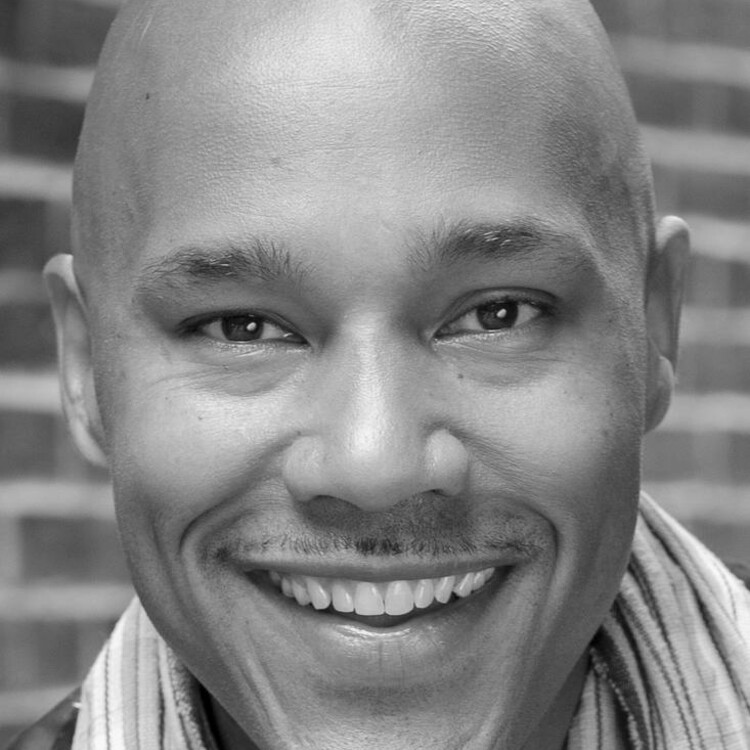

As co-leaders of ArtsEmerson, we (David Howse and Ronee Penoi) are committed to living and leading in a present deeply informed by where we come from, and we do so with intentions for where we are going.

Black and Indigenous communities experience disproportionate violence and are frequently the most marginalized of BIPOC communities. However, the very structure of settler colonialism that we live in, which creates this dynamic, also pits these communities against one another. There is anti-Blackness in Native communities, and historically there were Native people who owned slaves. There are also stories of Native communities giving their lives defending Black freedmen and Black leaders who supported Native erasure as a way to strategically gain footing in society. We could go on. However, powerful change happens when communities come together in solidarity. This solidarity happened during the Civil Rights Movement and, more recently, during the protests at Standing Rock and after the murder of George Floyd. We believe that moving towards kinship, solidarity, and intersectionality is the next step towards systemic change in our country. However, there is crucial listening, reckoning, and acknowledgement—if not healing—that is necessary in order to come together across differences and create a shared vision for a future that benefits all.

The majority of our arts organizations in the United States are rooted in a leadership model that replicates and perpetuates this storied and oppressive past—a past in which a privileged few dominated those with less power and influence, and in which Eurocentric logics and approaches were prioritized over Black and Indigenous methods of knowing. This structure has been successful for some people but not all.

Our shared leadership model aspires to be a decolonized leadership model, one that reimagines, reshapes, and restories the role that organizational leaders can play in leading their institutions.

In 2015, ArtsEmerson committed to a model of shared leadership in which multiple leaders simultaneously manage and direct the organization. This value is now profoundly ingrained in the culture, and the entire team understands that shared leadership is a mindset, not a structure. What is the meaning of that? This mindset is the belief, attitude, and philosophy that leadership is not the primary responsibility of a single individual, but rather an approach that can be distributed and practiced by multiple individuals at various organizational levels. This is not dissimilar from many forms of Indigenous tribal leadership (of which there are many), in which an individual may be tasked with leadership on a particular matter, but all have a role in the leadership of the tribe. Our shared leadership model aspires to be a decolonized leadership model, one that reimagines, reshapes, and restories the role that organizational leaders can play in leading their institutions. In our work, we seek to embody a leadership model that prioritizes inclusivity, is respectful of cultural differences, enables individuals to fully lead from their position of influence, and breaks free from the constraints of our colonial past.

We (David and Ronee) have been engaged in this shared leadership model since Ronee’s 2021 arrival in Boston, Massachusetts. During the recruitment process, we engaged in a substantive discussion regarding our shared belief in the concept of shared leadership. We agreed to support one another, clear the way for one another, and promote one another’s activity. We committed to putting our finest thoughts and actions at the disposal of whomever makes the final decision on a given issue or project. Both Ronee and David have multiple and complex identities, but we choose to emphasize the identity that best characterizes who we are as human beings: David is a Black man, and Ronee is a Laguna Pueblo, Cherokee, and white woman. Along with these two distinctions, we share so much and have so much in common. We are frequently reflecting on how our identities and our shared leadership inform accountability. We need to support each other in being accountable to the communities we hail from, to the city of Boston, to the larger arts field ecology that is in a key moment of crisis, and to ourselves and our shared (and not shared) values. This requires deep listening, agreeing to disagree, radical support, and transparency. In a world that emphasizes the solo leader and “genius,” and that wants to attribute credit (or blame) to one key person, the trust and buy-in that is required for shared leadership is palpable. It is a daily exercise, a commitment, and like any living thing, requires care.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here