Making Space: Consent, Collaboration, and Queer Access Intimacy

With Guests J.C. Pankratz and Emmett Podgorski

Nicolas Shannon Savard: Hello, and welcome to Gender Euphoria: The Podcast, a series produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. I’m your host, Nicolas Shannon Savard. My pronouns are they, them, and theirs. In this episode, we are returning to Seahorse by J.C. Pankratz. In April, I directed the first full production of the play. It premiered at Maelstrom Collaborative Arts in Cleveland, Ohio with the support of Synecdoche Works, the Baker Nord Center for the Humanities, and the Humanities in Leadership Learning Series at Case Western Reserve University.

Through that last program, I am just finishing up a yearlong postdoctoral fellowship, which has allowed me the time and space for a lot of the research that’s gone into this season of the podcast, and they were open to me directing this production as part of a larger practice-as-research project. In other words, achievement unlocked! I convinced a university to pay me to go make trans and queer theatre friends and to pay those trans-queer theatre friend artists for their work. I’ll put a link in the transcript to the show’s webpage with further exploration of that research project. There’s a program, a recording of the talk, production photos, blog posts—all exploring how feminist performance practice, queer theory, disability aesthetics, and principles of community engaged art making informed our approach to the design and the collaborative process.

As for the production itself, here’s how I described it to the audience. One of the many things that drew me to this story was the way that the central character, Reuben, even as he is experiencing some of the most vulnerable, isolating moments of his life, invites us into his world. As a trans artist and one who knows all too well how rare it is that we see trans characters rich in our lives on stage, I wanted to find a way to heighten and draw out that sense of intimacy and connection. How might we create opportunities for the audience to access Reuben’s inner world in all of its messiness and contradictions?

One method we’ve explored in this production is surrounding Reuben with an ensemble who performs live audio description, which we’ve adapted from the original stage directions. We hope this verbal description of visual information will serve its more typically intended function as an accessibility tool. At the same time, we’ve broken the rules a bit—queered it, if you will. Our audio describers tend to stretch beyond that role, telling us what can be seen on stage and much more that can’t, which only seems appropriate in a story that blurs the boundaries of sex and gender, space and time, what is real and what isn’t.

They will mostly be hanging out at the edges of the stage describing the action and the visual landscape of the story for you, but they’ll also talk to Reuben and to each other. They’ll hand off props, make the set changes, and are often responsible for the new elements introduced into the scene. They are characters in and of themselves. They are all in Reuben’s head, and they are very real.

What this episode is going to be is a series of reflective conversations on the production process as opposed to the show itself. I’ll chat with J.C. Pankratz and Emmett Podgorski, who played Reuben, about using intimacy direction and consent-based practices from a queer-trans perspective to create a more accessible rehearsal room and in support of the collaborative process. It weaves together several of the themes that you’ve heard so far this season, as many of the conversations I’ve had with guests on the podcast have informed how I approached the production from auditions to opening night and beyond. I am excited to get to share a bit more of our process with you and hopefully give some concrete examples of how some of the tools and ideas we’ve talked about in previous episodes played out in practice. And so, here we go.

Rebecca Kling: Gender euphoria is...

Dillon Yruegas: Bliss.

Siri Gurudev: Freedom to experience masculinity, femininity and everything in between—

Azure D. Osborne-Lee: Getting to show up as your own self.

Siri: Without any other thought but my own pleasure.

Rebecca: Gender euphoria is opening the door to your body and being home.

Dillon: Unabashed bliss.

Joshua Bastian Cole: You can feel it. You can feel the relief—

Azure: Feel safe.

Joshua: And the sense of validation—

Azure: Celebrated.

Joshua: And actualization

Azure: Or sometimes it means—

Rebecca: Being confident in who you are.

Azure: But also to see yourself reflected back.

Rebecca: Or maybe not, but being excited to find out.

Reuben is trans. He is a trans man. He is proud of it. He knows it, and it’s not part of Reuben’s universe to explain who he is or defend himself or anything. He just is who he is.

Nicholas: I am here with Emmett Podgorski recording, for the first time ever, an in-person interview for this podcast! All of them have happened over Zoom. This is exciting that I get to be in the same room with a guest. Before we dive into talking about queer-trans intimacy work in Seahorse, would you like to introduce yourself? How do you identify as an artist?

Emmett Podgorski: So as Nicolas already said, my name is Emmett Podgorski, pronouns are he/him. I would identify myself as a transgender man and a queer theatre practitioner. I mainly do acting, but I just really love creating any part of theatre I can.

Nicholas: What you are hearing in the background is George the cat.

Emmett: He has the zoomies.

Nicholas: I’m going to leave it in. So, you were the very first person involved with this production of Seahorse besides me and J.C., so I want to ask you a little bit about what drew you to this role, to Reuben’s story. We’ll start there.

Emmett: Okay. So I first read the script, and it was just a very beautiful piece. It was very down to earth. It was very grounded, but also very poetic and very weird and surreal at some parts. You just got such a nice insight into what Reuben is going through and the struggles that he’s dealing with throughout the piece. And as someone who is trans and who is neurodivergent, I just related to him so much. Even though I’ve never experienced the sort of thing he went through specifically, I could relate to him a lot, and I just really love that.

Nicholas: So before this show, you’d played, if I’m remembering correctly, only one explicitly trans character.

Emmett: Yes. The play before I was in was called Log Cabin by Jordan Harrison, and I played the character Henry, who was a transgender man, and he also doubles the role as Hartley, which is a baby.

Nicholas: All right. Samuel French synopsis: “when a tight-knit circle of married gays and lesbians comfy in the new mainstream see themselves through the eyes of their rakish transgender pal, it’s clear that the march toward progress is anything but unified. With stinging satire and acute compassion, Jordan Harrison’s pointed comedy charts the breakdown of empathy that happens when we think our rights are secure, revealing conservative hearts where you’d least expect.”

Emmett: But then, Ezra is having trouble accepting Henry being a man. So the play is mostly about these cis people learning to accept this trans person.

Nicholas: So for this show, coming off of that one that’s, like you said, about cis people learning to accept this trans man, what did it mean to you to be taking on this? Essentially, it was written as a solo show, an hour long, entirely centered around just Reuben and his experience.

Emmett: It was definitely intimidating. The first time I read the script I’m like, “Oh my gosh. I love this, but am I capable of this?” So it was terrifying but I’m like, “When am I going to get a chance like this again? I need to do this. This story needs to be told. This story... I want to be the one to share this story.” And just the fact like, like I said before, the role I played before was very much a trans person written for cis people. The playwright is cis. Everyone else in the cast, I believe, is cis, so I was the only trans person in the cast. So yeah, getting to go from that to a space where everyone is queer, pretty much everyone is trans or nonbinary—under the trans umbrella—everyone is neurodivergent, it was two completely different experiences. It’s also a completely different experience performing these two roles.

Like I know... With Henry, there was maybe one or two moments where it’s like Henry getting to be unapologetically trans, versus Reuben. But that entire role, a lot of it was about educating the audience about being trans as Henry or what the queer community faced pre-Trump, during Trump, after Trump, and how we’re all still growing and stuff. It was so much about educating the audience about these things versus Reuben was telling his story.

Nicholas: I think there’s plenty to learn from Reuben’s story but it’s not—

Emmett: It’s not about that.

Nicholas: About educating.

Emmett: It’s not about that. That’s not the priority with Reuben, I feel.

Nicholas: I think you have to work a little bit harder to get your education from Reuben. He’s not going to explain himself.

Emmett: He’s not. He’s not. He doesn’t need to.

Nicholas: Reuben’s story is just going to keep going to all sorts of places. It’s your job to keep up.

Emmett: Yes. And even if you can’t keep up, does it matter? If that’s possible—

Nicholas: If you can’t keep up, listen to the poetry. Listen to the poetry.

Emmett: Yes. Like Reuben is trans. He is a trans man. He is proud of it. He knows it, and it’s not part of Reuben’s universe to explain who he is or defend himself or anything. He just is who he is.

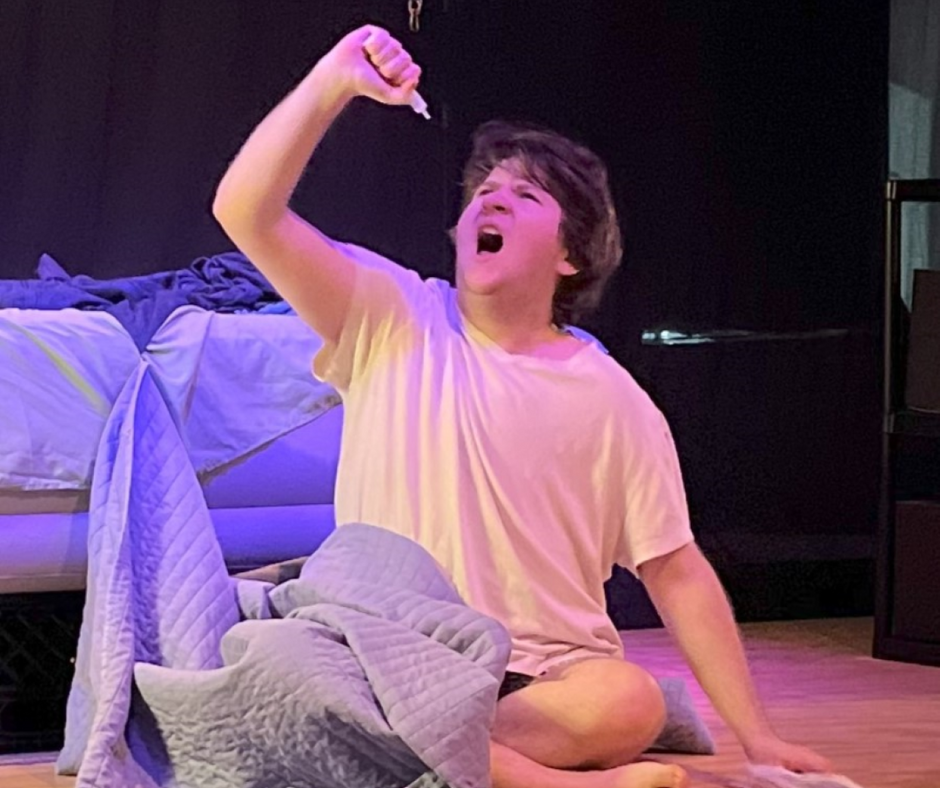

Emmett Podgorski in Seahorse by J.C. Pankratz at Maelstrom Collaborative Arts. Directed by Nicolas Shannon Savard. Scenic design by Cassie Harner. Costume design by Nicolas Shannon Savard. Lighting design by Kassie Rice. Photo by Malcolm Miller.

Nicholas: And jumping over to J.C. for their thoughts on the production.

All right. So, back again with J.C. Pankratz. Over a year later, we have now produced Seahorse in Cleveland as part of the Cleveland Humanities Festival and flew you out here to come and see it, which was exciting. Of the cast that I’ve gotten to follow up with for coffee, and the students, many of them have said getting to connect with you about the play was one of the most meaningful parts of the production experience. So, they have lots of love and respect for you.

J.C. Pankratz: I really had to hold off on making just the most choked sob noise into the microphone.

Nicholas: They were very excited to ask you all of the questions about all of the things and then have you answer some of them and then refuse to answer others.

J.C.: That’s part of the magic.

Nicholas: Yeah! Yeah.

J.C.: Totally.

Nicholas: So when I came to you with this idea of turning the stage directions into audio description, I remember your initial response was… I cannot remember the name of the Beckett play with just the mouth in the darkness talking-

J.C.: Oh my god. Not I? Yes, yes.

Nicholas: And that was not what we did.

J.C.: Right.

Nicholas: What were your impressions, having seen what we actually did with it?

J.C.: Yes. So it was very different from Samuel Beckett’s Not I. First, I think I just learned a great deal more about audio descriptions for the theatre and what that is like. I guess the process of making them was not something that I knew a lot about. And so, being able to see you and your collaborators imagine the audio descriptions from the inception of creating this version of the show, I think, was really interesting and really, I think, centered accessibility in a way that I learned through working with you that often this process does not really take into account. It was really just lovely to see something where this is really important to this vision of a play from this director, and we’re going to grow this aspect of the play like any other concept that would be involved in creating the play around lights or motifs or things like that. The way it took shape as almost a new imagining of a chorus, I thought, was so interesting and provided another way that intentionally we can weave description in and create another version of theatrical experience of this play—

Nicholas: Got to give one of our actors, Minor Stokes, the credit for the formation of it as more of a chorus.

That was their reading that they came to their audition meeting thing with, and I hadn’t quite thought of it that way yet and then cast them and Sam and Justin and was like, “Oh, okay. I can play with this now. Here we go. This is more exciting than what I had been doing, which was one of you talking at a time.”

J.C.: Right. So that’s so magic. I didn’t know that. That’s so—

Nicholas: Yeah!

J.C.: Really speaks, I think, to... I mean, you were just saying sometimes a director hears something in a room like that and is like, “Well, that’s not what I thought of first. I don’t want to do that,” but being open to new re-imaginings of a new re-imagining, I think, is really such a gift and I think this particular group of people too. I mean, I think what I was reminded of when I came to see the show and I got to meet all of these lovely people, how much it reminded me of being a younger person in the Midwest and the reason I liked to go make theatre because I found that there were people there who were interested in creating things, wanted to make each other feel safe and collaborative.

And when I think of the performers and all of our other collaborators who were a part of this project, that’s just a part of it, for me, that really sings. Where it’s like this is such a group of people who really just wanted to make this story happen. There’s a group of people who felt kinship in this story because of their identities, who they are as queer and trans people; and it was like in making stories about queer and trans people, we also bring queer and trans people together. And hopefully, we give them a check also, which is really nice in our lives, but I think—

Nicholas: Major goal of mine: to make sure all of the professional artists working on this got paid like professionals.

J.C.: Yes. Right. Incredibly important, incredibly important—

Nicholas: I put my humanities program people through their pacesat the , figuring out what the process was for making my research funds work that way.

J.C.: Exactly. Right.

Nicholas: When I was like, “So, you’re not getting a book—”

J.C.: We are getting an experience.

Nicholas: “We’re going to get...” What was the title of my thing? It’s like “Queer-Trans Intimacy and Disability Aesthetics in J.C. Pankratz’s Seahorse: A Talk, a Performance, a Gathering.”

J.C.: That’s right. I love that.

Yeah. I just think it was such a... The play itself is a lot about what do you do when you are in a place where you are removed from community, even though Reuben certainly has community. It’s interesting because in my imagination I’m like… because Reuben is directly addressing us the whole time, by the end of the play, we have become that. We’re part of his community now. We have been part of this process. He has invited us in a moment of great hope and of great grief to sit with us and do this. And I really loved being able to see a physical manifestation of that also on stage.

Nicholas: That sense of community and the group of collaborators that I gathered, I think part of that comes back to how I started the audition process in the first place because I didn’t do normal auditions for this where you come and give me a monologue or a cold read or something like that. I believe it was Azure Osborne-Lee. In their episode we talked a bit about curating the rehearsal space and very intentionally bringing particular people together in the room, and it is really thinking about that in this rehearsal process, even from... I set up auditions as more of a conversation. I just set up meetings with people. What I went in asking was, “What draws you to this story specifically? What do you find exciting about it as an artist?” and we’d talk a little bit about how you work as a collaborator and I tell them a bit about me and how I work as a director just to get a sense of like, “Do we actually want to work together? Is this going to work?”

I skipped over this during the interview. There was a third question that particularly shifted the typical audition dynamic which was, “If I’m not able to cast you in an onstage role, are there other ways that I can keep you involved? Are there other parts of the project that interest you or other skills that you might want to lend to the story?”

It came from this place of wanting to challenge the usual sense of competition and scarcity and instead, create an invitation into a collaborative relationship, sending an overall message that there’s plenty of space. If you want to be part of telling this story, then I want you to join us. And that reframing ended up working out particularly well. It’s how we ended up with Cassie Harner, drag name Dusty Bucket, working as our lead designer; and it’s how I ended up pairing James, one of our students working on tech, with Justin, one of our actors who was also a designer, so that he could learn sound design and be mentored by him.

And I did an open rehearsal style audition. I gave folks a devising exercise with the fall from the sky to the bottom of the sea, and I just left Emmett and Justin for fifteen minutes with a bag of props and, “Just stage this. You can use anything in the room. Go for it. Just set up these spaces to be like, ‘Let’s test out what it’s like to work together and see if we want to do that.’”

J.C.: I think, especially for a play like this where people are not speaking in the most plain, straightforward language, that there is the instinct to really go to that original model and being like, “You have to test people.”

Nicholas: I need you to bring me a two-minute Shakespeare monologue to prove to me that you can do it.

J.C.: This is a way to show, I think, that we don’t always have to do things the same way, that there’s a lot of value in understanding that there are more ways to get people into the rehearsal space just like a question, and it’s like to me when I’m listening to you, it’s like, “Oh, the most important thing a person should be able to do in this rehearsal space is to be able to collaborate and share ideas,” and that’s the number one thing they should be able to do. That’s what we’re going to explore in the space, and we’ll go from there, and I think that makes sense. It is. I think it’s a really interesting way to try doing something, and I think it yielded results that, I think, really agreed with your style and what you were trying to do and then what you were all trying to do because that ended up being the main goal.

Nicholas: I will say the traditional model of auditions would’ve been much faster. It was hard work and a lot of coordinating to meet all of the people, and time intensive, and really required me to draw on connections to the local arts community… which I only lived in Cleveland for three or four months when I was starting that process was... I am impressed I got people in the room at all, honestly.

J.C.: I mean, it’s a trust building thing too. Not only getting people in the room but being like, “This is how we’re going to do the process,” I think is a little bit more of reaching out an open hand. Not to say that it’s either the old model or this but certainly a gesture of a lot of faith as opposed to, “Well, how else are we going to get these two hundred people in to sing for Ado Annie?” There are different goals. There are really different goals, and I think that changing that process was really helpful even though I... And I think it’s important to acknowledge that there’s also a reason why it’s called a “cattle call” in other contexts.

Nicholas: Right.

J.C.: And we were very much not doing that. We were trying to not do that at all. What’s the linguistic opposite of “cattle call”? It’s like a “cat sunning”? Everyone is just like… it takes time. People are trying to be relaxed so—

Nicholas: The image I have in my mind is just like a sunny pasture.

We’ll come back to J.C. In a bit. For now, I want to turn the conversation back to Emmett to chat about how the design of that audition process rooted in developing relationships among collaborators carried over into the rehearsal room. We talk about access intimacy, and I’d like to drop you into a moment where we managed to capture that practice in action mid-interview.

Emmett: If you want anything to fidget with, let me know. I have... There’s like a whole drawer of it… That is the most neurodivergent thing to happen today so far, I think, to just pull out a bin under my couch of just art supplies.

Nicholas: I forgot my fidget toy, and Emmett has immediately met my access needs for staying focused during this interview. Amazing.

Emmett: Yes.

That’s part of the joy of Seahorse is us all just being like, “Oh yes, we’re all weird. Let’s just do what we need to do to make it work.”

Nicholas: Going back to thinking about this show as one that was very explicitly centering queer and neurodivergent experiences, as I was planning the rehearsal process, I was really guided by the principle of access intimacy which is a term coined by Mia Mingus, who is a badass disability justice writer-activist.But this idea of access intimacy seemed really important, particularly for our group of entirely queer and neurodivergent folks.

So, I’m wondering, a little bit, could we talk about how access intimacy showed up in the rehearsal process and what did that look like? What did that feel like? How did that shape experience of the show and the production process?

Emmett: So, I don’t know how much this particular thing I’m about to say will count as access intimacy, but it’s going to lead into the rest of the actual stuff, so just whatever.

Nicholas: Cool.

Emmett: I know one thing that really made the space comfortable for me is the fact that I had met you beforehand and we had been in contact beforehand, so I had you as a familiar face. But then, one of the other actors in the show, Sam Cocco, was actually in Log Cabin with me. So I had this other person who had been in another show with me, where I played a trans person, who I knew and had a relationship with. So having Sam in the room too was just a very helpful thing to have right off the get go.

Nicholas: That came up in our conversation during our audition interview that I had with Sam was, because I asked her, I was like, “How did you find this show?” She found it through you and was excited to possibly have a chance to work with you again and talked about that experience, and I was like, “Okay. This checks out. These two know each other. They’ve worked together well before. I am not creating a situation where Emmett is going to have to teach some random cis lady what it means to be trans.”

Emmett: Yes. But yeah, that was a big thing that really helped and just the knowledge I was going into this process with a cast that all knew that at least I was queer and I knew at least some people in it were going to be queer. That was such a safe thing to have versus other spaces I go into as a trans person. Like I’m not going into them as a trans person, I’m going into them as Emmett who happens to be trans but doesn’t necessarily want that to be a thing that he makes space for in other spaces.

But yeah, going into a space where I know I can take the space, I can as a trans person, or I have that freedom to do that was also very nice, and just knowing a trans director would know more of what I have been through than a cis director would have. So I knew I had that safety going in even before the first rehearsal started, so that was very nice. That was very nice. And at the first rehearsal, right off the bat, we were talking about what we needed to have success in the production.

Nicholas: Before our first rehearsal, the first read through, we did our little introductions. It was like, “Name and pronouns. What brings you here to this room today?” and I think we shared a moment of either queer joy or “artistic wonder,” and then before reading we were like, “Any access needs? What’s going to be helpful?” I pulled out the tiny clock from my office because there wasn’t one in the room and was like “I have no internal sense of time, this is what I need now. Also, pocket full of fidget toys. My access needs are now met. Yours are welcome.” And then, everyone just was pulling out all of their things from their pockets.

Emmett: Yes. It was beautiful and “button” was also such a good tool to have. That’s still something I’m using in my life

Nicholas: Button is the word the Theatrical Intimacy Education uses for their self-care cue. I used the same one with our cast.

Emmett: Do you want to explain it or should I?

Nicholas: I’d like to hear your explanation.

Emmett: Okay.

Nicholas: How do you use it?

Emmett: So with “button,” in the process, how we learned it is just basically if there’s a moment where things feel like too much, where it’s emotionally intense or you feel physically unsafe or you just need to breathe for a second, you can say “button” and everything stops, everyone breathes, you’re asked what you need, and then it’s provided for you. Or if you can’t verbally say “button,” you can tap twice or clap twice or something twice, which I really like because I like having nonverbal ways to get my needs vocalized or to get my needs heard. And then, what we ended up doing is… One of the cons of the cast of neurodivergent people–

Nicholas: And a very short rehearsal process–

Emmett: Yes–is that we talk a lot and we want to talk about everything and we all have a lot to say.

Nicholas: And every idea sparks ten new ones.

Emmett: Yes. So we would get off track and that would lead to stress because no one really knew how to be like, “Okay. Let’s be back on track,” and that was an access need of getting us back on track.

Nicholas: I think we might have known how to do it. Recognizing when it needs to happen is the challenge.

Emmett: Yes. Also, sometimes it could be intimidating to be like, “Okay. Stop talking. I want to work again.”

Nicholas: Right. Especially when the director is the one getting us off topic.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: Will own that for myself.

Emmett: Yes. But yeah, so we would use “button” in the rehearsal. Like if we started rambling too much, we’d be just like, “Button” and stop for a moment and breathe, get back into the head space we needed to. So that was really helpful.

Nicholas: Or we’d just hear in the background, just our stage manager, Kassie, just soft two knocks on the table. We’d all stop and breathe and be like, “Okay. Refocusing.”

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: We just all knew what it meant.

Emmett: It was like, there was a couple times where I would notice people would be talking and I noticed one or two people seemed stressed out because of the lack of focus, and I’d want to get back on task but I wouldn’t know how to bring that up. So once we started using “button” to do that, that was so nice to have because no one’s feelings were hurt. Everyone felt heard; everyone was able to vocalize what they needed.

My cat’s doing just parkour on his cat tower right now, and it’s fascinating to watch.

Nicholas: What are you doing?

Emmett: See, if George was a human, I would “button” right now and have him chill out. So I can’t do that—

Nicholas: Cats may or may not respect your boundaries. Cats rarely respect your boundaries.

Emmett: I’m going to take a picture of this for you to put in the show notes.

Making a surprise guest appearance, Emmett’s cat, George, dangles and stretches between the platforms of his cat tree. Photo by Emmett Podgorski.

Emmett: Okay. Anyways—

Nicholas: All right. Here we go. The idea is making a space where everyone is just set up to—

Emmett: Succeed, yes.

Nicholas: Thrive and be able to engage in the way that we need. Accommodation tends to be a very individualistic approach, but I think that’s the idea with access intimacy, is that there’s not any sense of shame or burden to having access needs. I think it’s really a cultural shift from a lot of the theatrical spaces that I’ve encountered. It’s just we walk in expecting everyone to have needs, and we set this expectation that like, “Alright. Cool. We’re collectively responsible for making sure that this is a space where everyone can have what they need to work.”

Emmett: Yes, and it makes such a great piece too in the end because if everyone’s happy working on it, then they’re going to put more into it, and it’s beautiful to have gotten to work in that space with all this to make what we got in the end.

Nicholas: I want to pick up the conversation again with J.C. Although they didn’t use the term “access intimacy,” they spoke to a very similar sense of ease, understanding, and orientation toward addressing barriers in their own work with fellow trans and nonbinary artists.

J.C.: [What is] really nice when I’ve worked with directors who are trans or nonbinary or both, [is] the immediate understandings around casting. I’ve worked with good cis directors who also understood that. I had to check in about it very briefly and then we don’t have to have that conversation again, but it’s really lovely to just know that understanding is going to happen. Speaking for myself as a playwright writing trans characters, whenever I go into a new process, even for something like a reading, I carry a lot of anxiety around having to make things clear. For me, it manifests as anxiety. I think maybe for other people it could manifest as annoyance or perhaps anger. For me, it manifests as a lot of nail-biting because I’m like, “Okay. Are they going to understand nuance around casting? Are they going to be able to communicate this to...” I think we were also in a unique situation in terms of who you had to answer to, for lack of a better phrase. There was a certain amount of freedom there in terms of the “institution”.

Part of the cast and crew assembly process and pulling people from all of the different places was also creating one of those spaces for this story where there would just be this baseline understanding of transness—where I wasn’t going to have to explain myself, you weren’t going to have to explain yourself, Emmett was not going to have to explain himself. No one in the room would have to worry about that.

Nicholas: I had a lot of freedom with this project to do what I wanted with it. I did have to make it research and give a talk about it to make it count as research.

J.C.: Right.

Nicholas: Separate academia problem. I think there was a lot of flexibility to get really experimental with it and break a lot of theatre norms.

J.C.: Yes. Mm-hmm. Yes, and I think that you didn’t have to explain to those people why we needed to hire trans people. Why... I mean, partially because I’m like, “I don’t know. How much do they know about what auditions are like?” But you have to spend a lot of time and resources going into the community to find people because this is a group that historically has been pushed to the margins of the theatre. Obviously, there aren’t no trans parts ever, but a lot less, or having bad experiences with casting. There’s so many... A myriad of things that go into how to get someone connected to an audition notice.

Nicholas: And how to field the responses to the audition notice that are… questionable.

J.C.: Right. Not only from people who need to be in the room–or not need, but we would really want them there–versus well-intentioned cisgender people who are like, “Of course, I’ll play a trans person. I’m an actor. I’ll do anything,” and then I’m like, we have to rethink the ways we teach people about stuff. There’s so much... God, we could talk for six hours to start unpacking that statement from a person who was just like, “Well, yeah, I want to work.”

Nicholas: We could have an entire separate episode dedicated to a few of the email exchanges in the audition process.

J.C.: The Gender Euphoria podcast outtakes.

Nicholas: Bonus episode.

J.C.: The mail bag is just emails that you’ve gotten and... Oh my god.

And I will say, it’s an effort of extraordinary labor because you were doing this by yourself. Whereas in other situations, somebody might have a casting person that they’re working with, or a producer—just a lot of other people who they have to talk to in a conversation. And the understanding that this is not going to be a thing that you could schedule from 3:30 to 6:30 on Tuesday and Thursday, this one week of February.

It was like, I’m going to need to go. I’m going to need to email people first. Teachers, I’m going to have to email community people. I’m going to have to really spread a wide net. I’m going to have to go to events and see if I can talk to people or have a community person introduce me to another person.” I think especially for someone who was new to the community, you put in an extraordinary amount of effort to figure out what were the appropriate, respectful, and authentic ways to go meet people who were involved in the performing arts scene or the drag scene or whatever to connect them with this opportunity.

Nicholas: I did attempt to recruit some folks at a drag show.

J.C.: Yeah?

Nicholas: I did! I was so close. I gave them my contact information and all the show information and failed to get theirs. And all of those little slips of paper are backstage, alcohol-soaked somewhere.

J.C.: Yes. But the thing is, too, is that I think about, hey, even if those people did not get involved with the show, maybe they will be more open to the next thing. It just leaves the door open a little wider to be like, “Oh, I think there are things for you here.”

So, I’m a very early career playwright. I have had the ability to interact with a lot of different institutions, some that are big and some that are small. I am often running into the problem of people being like, “We have one person we can ask. They’re not available,” because that’s life.

And then the question is like, “So who do you have or can you recommend someone?” and the thing is that I think that institutions really need to recognize that they need to... If they don’t have a relationship with trans, queer, nonbinary, anybody who is outside the gender binary, that theatre community, that they have to put in work like that to get them to want to be there. They need to have programming that speaks to that experience, whether that is the shows they’re putting on or what kind of audience outreach are they doing? What kind of people—

Nicholas: What kind of guest artists are you bringing in if you don’t have anybody already?

J.C.: Yes. Right. Do you ever offer your space to those communities as a way to acquaint people with where you are? And I think there’s lots and lots of possibilities but I think, A, because people believe this is new and these stories are new—they’re new to them—they don’t have the same type of long community relationships that they might have with other marginalized communities. Not even to assert that they have those relationships. We may all be in the same boat. This is really what I can speak to. You can’t just do it through the usual channels. You have to go to places and be like, “We have these opportunities. We have these people coming in.” You have to really go and build those things.

If you don’t have a person... Like, if it’s three days before something’s supposed to start and you’re like, “I’m going to find someone in this time,” no, you’re not. I mean, you might. I don’t want to be like, “No one will,” but it’s really hard and I have experienced this where then we don’t have the right person. But all of this is to say that it is really great working with you, working with other trans and/or nonbinary directors. I think because we probably share some of those experiences, we’re just able to talk about it in a different way immediately as opposed to having a check-in.

There’s something unspoken about just being like, this is... You understand that this is a really big deal. And it may be a true understanding of like, “I understand all of the emotions that must be happening.” Maybe that’s it. I think maybe it’s truly knowing that these are things that, even if you have done this a hundred times, are frustrating and annoying and make you sad and mad. And I think that there’s just a knowing that in the same way that the name of the game is we know we have to deal with it, the name of the game is also that it does not feel great inside.

Nicholas: With all that, I think part of the cast and crew assembly process and pulling people from all of the different places was also creating one of those spaces for this story where there would just be this baseline understanding of transness—where I wasn’t going to have to explain myself, you weren’t going to have to explain yourself, Emmett was not going to have to explain himself. No one in the room would have to worry about that. Just having to walk in and be like, “Ugh. Are they going to get it? Has this been considered before? And if I bring it up, is anyone going to understand or am I going to have to dive into a twenty-minute educational session that I don’t want to have to do because it’s 9:30 p.m.?”

J.C.: We don’t have time. We have so many other things to do.

Nicholas: For this last segment, I’m coming back to Emmett. We thought it might be useful to model some of the conversations we had applying consent-based intimacy tools from a queer-trans perspective, and we thought it might be useful to other directors, actors, intimacy choreographers to hear some of the things that we were thinking through as we worked through the specifics of the show. The most choreography heavy scenes were the ones where Reuben is performing the insemination.

I’m going to play the audio of the first of those scenes performed here by Emmett, Samantha Cocco, and Minor Stokes. Just to give you some context for what we’re talking about. Heads up, the scene involves detailed and explicit description of the artificial insemination process and a whole host of bodily fluids. If that content is outside your boundaries, you’re welcome to skip ahead past the next two minutes to the end of the scene or to where we’ve moved on to our discussion of costuming. That starts just a little before the forty-nine-minute mark.

As is typical with intimacy work, we started with the story.

All right. Set the scene. Reuben’s bedroom. It’s 5:00 a.m.. It’s time. We are ovulating.

Minor Stokes: Phone is tossed to the bed. The cap of the cup—

Samantha Cocco: Carefully—

Minor: Unscrewed.

Samantha: Okay. Now, draw the semen into the syringe.

Minor: It’s up.

Samantha: Okay. Now, just lean back all the way in the bed—

Minor: Under the blankets, here. A tiny moment of mental debate.

Samantha: There’s no time. Tent your underwear with one hand and then slide the syringe in with the other and then—

Minor: It’s awkward—

Samantha: It’s uncomfortable for a second. Pull out, get the lube.

Minor: He has to find it in the drawer with just one hand and then he’s got to open it up without even looking at it—

Samantha: A practiced skill for sure.

Minor: Never like this. Okay, lube retrieved.

Samantha: Okay. Both hands back in the underwear, slide the fingers in first, then the syringe, and then push the plunger down, and now, it’s done. It only takes a second or two—

Minor: But it feels like forever. We can see it on his face.

Samantha: Pull the syringe out, bend your knees, and hug them to your chest. Nothing left to do but wait for a while.

Minor: He covers his face with his hand. You have lube on your face now. You can’t wipe it off with your hand.

Samantha: Maybe a pillow, or a corner of the sheet?

Nicholas: Yeah. Let’s talk a little bit about how we went about staging that moment and the things that we were thinking about for it. As is typical with intimacy work, we started with the story and what do we need from this moment. I think the choreography itself, we started way before Reuben even got into bed.

Emmett: Yeah. I think when we first started doing it, we just had the random assortment of furniture you’re able to scrounge up from the basement.

Nicholas: And my air mattress!

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: And we had to work into the choreography where you needed to sit on the air mattress to not tip it over.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: Which probably took almost as long as actually doing the insemination, figuring out how the air mattress needed to be set up on the crates to not tip.

Emmett: Fun times. So with that, for that rehearsal, it was a one-on-one rehearsal just you and me which was definitely how those things, I feel, should be. Like as an actor, just keep it... Well, if the actor is comfortable with it. Yeah. That should be—

Nicholas: Often, it’s recommended that there’s a stage manager in the room, documenting what are we coming up with for the choreography and just having a third person. But Kassie wasn’t able to make that rehearsal and I hadn’t trained her on it yet anyway. But we did check in ahead of time like, “Hey, we know it’s just going to be the two of us in rehearsal. Would you like to do this tonight?”

Emmett: Yeah. Definitely.

Nicholas: I think I gave you the option to be like, “We can do this a different day if you would like.”

Emmett: Oh yeah, I was ready for it that day though. So yeah, for me, I felt very safe in this space already by that point. The stuff we had already established helped a lot. So definitely starting early on with making everyone comfortable is the way to go, for sure. Which seems like a, “No, duh,” type of thing but some directors are like, “Okay, everyone, read your scripts, kiss each other. You just met five minutes ago. Who cares?”

Nicholas: And this is why intimacy direction exists.

Emmett: Yes, exactly. So yeah, we talked through it all. We talked through the movements and the words going on with the movements and what need to be what words, and then we ran just the general movements, which involved me miming inseminating myself with a syringe.

Nicholas: And we used a highlighter for a placeholder.

Emmett: Yes. So many random things were used as a placeholder like highlighters, colored pencils. Position the item to make it look like I was inseminating myself with it, which during the production was done with layers of clothing on me. I had a pair of tight boxers over a baggier pair of shorts and there’s a blanket on top of all of that so I just mimed it and we worked on how to make that look realistic, how to do it in a way that I felt comfortable doing in front of a room full of people while still looking what needed to look like.

Nicholas: I think we talked a little bit about even during the choreography like, “Where is this going to take place? What are you going to be wearing?” Making sure you know that you’re going to have a layer underneath those shorts and really no one can see where exactly your hand is so you’re in control entirely of placement of where is this going on your body.

Emmett: Yes, so it was that and figuring out how to tell what I was trying to show with the limited visuals, which I made up for with my breath and with my breathing. We worked on that a lot, but we talked through it. We worked on little bits. We mixed it with the rocking. I think one of the comparisons I made was the game where it’s the maze with a little metal ball where you turn the maze to get the ball into the hole. Except instead of the ball into the hole, it was a semen into the… whatever. And instead of the game, it was my hips.

And it’s like that’s another thing that helped a lot was having little silly things to laugh about during the rehearsals, to make it fun in the rehearsals. Make it fun for Emmett to be doing it so that while Reuben’s doing it, Emmett can help Reuben do it.

Nicholas: Yeah. The language that we use in intimacy direction is a de-loaded process and a desexualized process.

Emmett: I like that. I like that.

Nicholas: To have it be less intense of a moment. And also figure out what exactly Reuben is doing with his hips because I tried so hard to find what these exercises were that the playwright had described in the script and my research came up short a lot. So it was also a process of figuring out in the body what exactly is he trying to do? What is happening? Why is he doing this? Marble maze.

Emmett: So lots of communication, back and forth between what the director needs versus what the actor needs versus what is comfortable versus what gets the story across. Because yes, we do need all the access and intimacy but also we’re still telling a story, and that’s something that very much is a part of it. So it’s a balance at the end between having what you need versus having what makes everyone feel safe.

Nicholas: All right. Let’s talk about costumes. I think that might also be something that might be helpful for other directors, actors, costume designers even, to hear. We don’t always apply intimacy work to costuming but I think, especially in a trans context, that seems really important. Let’s talk costumes.

One of the tools that we had at the beginning of the process was thinking about different kinds of risk boundaries and how to tell where you want to set those and how that applies to how much of your body you want to be exposed, literally, physically, and also, how does that feel emotionally for you? Holding both of those things in mind. All right. So Reuben is in his underwear the whole show. What was the description of the boxers?

Emmett: Fun but not outrageous pattern, I think it was?

Nicholas: Oh, “a nice but not outrageous pattern.”

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: Because Sam says, “Nice boxers,” and Minor corrects, “A nice but not outrageous pattern.” We talked about this during choreography too, that you would have a tighter layer underneath so that when you’re doing the insemination, you’re not just exposed entirely to the audience at any point, extra layer of comfort. Yeah. With that, we talked a bit about how you would need a baggier layer over to be able to do the insemination and the movements that you needed.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: All right. So we have the monk robe you’re wearing for most of Scene Three. How would it work with your boundaries to be shirtless underneath that for that moment at the end of the scene to draw on yourself? I can imagine some other options where we could have a very low-cut muscle tee type thing.

Emmett: I am fine with whatever. I’m fine with being shirtless. And at that point, you asked me how I felt about it.

Nicholas: I did. Yes. I think you gave me a lukewarm, “I’m fine with it.” I’m like, “Okay, but do you want to be?”

Emmett: I’m like, “Heck yeah.” Because for me, as a trans person and just as a human in general, because society sucks with the body image issues. Being trans, you have the whole dysphoria on top of that. And my body used to be something I felt a lot of shame about for so many reasons, and it’s been part of my personal journey to be at a point where the idea of being in a play where I have my body exposed, that sounds empowering. So that’s why I wanted to do it.

Past Emmett… I’m going to draw from a real-world experience here. I was doing a show a couple years ago where part of my costume involved a very skintight layer. This was after I’d gotten top surgery. And I remember just trying it on in a costume shop and being like, “I am so glad I’m not going to have to bind in this.” But it wasn’t a conversation with me that’d be like, “Hey, are you comfortable wearing this skintight body suit?” It’s this, “Here, try on this skintight body suit.”

So it’s nice to not just have it be an expectation, to have it be a conversation of what people wear. And that’s really any sort of costuming in theatre, I feel, should have a conversation between the actor and the director and costume person about what you’re comfortable with, like whether it’s levels of exposure or what shape the clothes are.

Nicholas: If we can get people to get down with cut and exposure and boundaries around that, check-ins around that… which I think comes back to having some of these conversations as early as you can. At costume fitting is probably not the best time for it because things are made already. Things are picked out already. But just having that boundaries check-in before you go to pick things out… which also the director would need to facilitate making time for that, building in that kind of time to the rehearsal process.

And then finally, Reuben is naked at the bottom of the sea. I assured you you would not be fully naked at any point during this show. That seemed unnecessary.

Emmett: That sounds like the one limit. That’s the one I have as an actor at the moment.

Nicholas: I was not especially interested in asking you to be exposed quite that much.

So I think I told you a bit about what we were planning for, what the ocean was going to look like, and how you’d be wrapped up in a whole bunch of blankets from the bed that make the sea. We talked through some options of... Checked back in about the conversation of like, do you want to be shirtless in this scene? Do you not want to be... We can hold the ocean blankets at any point on your chest. If your shoulders are exposed, that can communicate “naked,” and we can go with that. I think that was about the upper limit of where I felt like as a director, that I could be like, “Okay. This still communicates what it needs to for the story.”

Emmett Podgorski, Samantha Cocco, Minor Stokes, and Justin Miller in Seahorse by J.C. Pankratz at Maelstrom Collaborative Arts. Directed by Nicolas Shannon Savard. Scenic design by Cassie Harner. Costume design by Nicolas Shannon Savard. Lighting design by Kassie Rice. Photo by Malcolm Miller.

Emmett: I think that shirtless aspect was the biggest thing with that just because it’s such a big thing to deal with, with that.

Nicholas: Right. I think we talked a little bit, too, about how you would be able to control how exposed you are because you’re holding those blankets.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: You can set them wherever you like on your body. There was also the moment transitioning from the sea back into the bedroom where you’re just swimming upward center stage for ninety seconds while the bedroom reassembles around you. I gave you the option of putting your shirt that you had entering the ocean back on for that if you wanted to.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: So that you didn’t just have to be center stage, shirtless—

Emmett: Pretending to swim.

Nicholas: Pretending to swim forward, waiting for the set change to happen.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: In very slow, dance-y choreography.

Emmett: Now, by that point, I was so emotionally and physically tired. It was a nice little break to stand there for those few seconds.

Nicholas: Yeah. In the dress rehearsals in the couple of performances, I think you made different choices on different nights.

Emmett: Yeah. That was mostly technical more than anything else.

Nicholas: Okay.

Emmett: Because I’d be there and be like, “Oh, the shirt’s on. Okay,” or like, “Oh, I forgot to put it back on. Okay. Oh, it’s lost in the sheets.”

Nicholas: How did it feel to know at least the option was there?

Emmett: Definitely good to have that option.

Nicholas: What I want to highlight now is just opening up the conversation, presenting multiple options for what could we do, making sure I, as a director, I’m letting you know I am open to a range of possibilities here.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: There’s not... If you establish a boundary, you are not jeopardizing my artistic vision.

Emmett: And probably also for directing, make it clear if there is something that’s like non-negotiable. Make it clear before you even have auditions. Like if you need an actor to be shirtless, be like, “You need to be shirtless. If you want this role, you have to be shirtless. No compromise.” Just like an actor going into it who might not be comfortable with that won’t go in, get cast, have to be shirtless, and be uncomfortable or get into an argument.

Nicholas: Or they just don’t say anything, and they come out on stage and can’t be present because their needs are not being met or addressed at all.

Emmett: Yes.

Nicholas: Last couple of questions that I’d like to close with. I’d like to invite you to give a shoutout to a member of your queer-trans artistic family tree who has supported your work, mentored you, inspired you, or generally shown you a path forward to where you are, shown you possibilities.

Emmett: I feel obligated to give a shoutout to Sam since I talked about her a lot during this. Obligated in a good way. Love you, Sam. I also like to give a shoutout to the director I mentioned earlier, Eva and Cory, who also co-directed Log Cabin and the rest of that casts and the rest of the casts of Seahorse and crew, of course, naturally—Minor, Justin, Kassie—because you all made that process so amazing and you guys are all so amazing. I can’t wait to see you all again. I hope you all are listening to this and just a shoutout to all the theatre gays in the world doing your gay thing. Keep doing it.

Nicholas: And finally, we leave you with a moment of gender euphoria which Emmett delivers as a delightful, impromptu manifesto.

Emmett: Queer euphoria for me is being able to live my queer authentic self. Whether it’s playing Reuben, this beautiful deep role or playing Squidward, a role that while not as deep is still fun and I can use my queer neurodivergent self to make it the best I can. Like it’s beautiful that no matter if it’s a trans role or not, I can still use that part of me in my art.

Queer euphoria is just going out in my daily life as Emmett as this weirdly dressed person.

Queer euphoria is overthinking my queer euphoria because I’m just trying to be Emmett and I love being Emmett and being able to live in the world as me as this weird trans person who talks a lot and wears weird clothes is my queer euphoria.

Nicholas: This has been Gender Euphoria: The Podcast, hosted and edited by me, Nicolas Shannon Savard. The voices you heard in the intro poem were Rebecca Kling, Dilon Yruegas, Siri Gurudev, Azure D. Osborne-Lee, and Joshua Bastian Cole. The show art was designed by Yaşam Gülseven. This podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this series and other HowlRound Podcasts in our feed on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and wherever you find your podcasts. Be sure to search “HowlRound Theatre Commons podcasts” and subscribe to receive new episodes.

If you loved this podcast, post a rating and write a review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content on howlround.com. Have an idea for an exciting podcast, essay, or TV event that the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to the commons.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here