"So who owns Play House, then?"

It's a good question. I take a moment to consider how much of this question I'm going to answer and what is actually being asked. I have a bit of a problem with oversharing sometimes, and I'm talking to a twelve-year old kid after all. But he's curious and has been spending a lot of time talking to me lately, asking me questions about my life, sharing kid gossip, or letting me know that it was definitely not him who threw that tennis ball against the window. In the eleven years I’ve lived and worked in the neighborhood, I’ve watched this kid grow up. So I explain that, while I manage the space along with Gina Reichert and Liza Bielby, Play House is owned by a nonprofit. We're looking at collective ownership models, but it’s tough because of the way the city of Detroit zones property. I talk for close to a full minute and the kid nods thoughtfully. "Do you know what a nonprofit is?" I ask him. "Yeah," he says, "it means you don't make any money" and now I'm nodding thoughtfully because, you know, the kid's not wrong. Before I can respond, he hops back on his bike and rides up the Play House ramp and onto the porch, where he quickly turns and jets back down, twisting and turning around the ramp's curves before speeding off towards home.

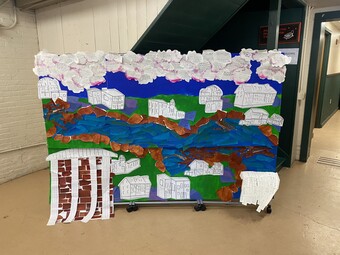

Play House is a two-story house that has become a neighborhood performance space, a laboratory for artists, a place for community gatherings, a studio space, and a school, among other things. It's owned by Power House Productions, an artist-led nonprofit based in our neighborhood and run by Gina Reichert. The Hinterlands, a performance company directed by Liza Bielby and myself, have created our theatre work in Play House since 2013. That year is also when Bangla School of Music, a school for both traditional and contemporary Bengali folk music run by Akram Hussein, began using the space as a home for their classes and concerts. The space has hosted artists from around the world and down the block and has also been used as a space for workshops, political organizing, film shoots, community sing-a-longs, international collaborations, dance parties, and both experimental films and kids’ movies. Liza and I live down the block from the space, about a two-minute walk away.

The difference between the pre-pandemic life of the space and its life now is stark.

A few years ago, we started building an ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) compliant ramp in the Play House side-yard. Rather than a standard ramp, we decided on something more meandering that would wind through the trees planted in the side-yard while still meeting all the elevation requirements. It was finally finished in the fall of 2019, right before a Bangla School of Music concert/recital. There were somewhere between fifty and seventy-five people at the event, including a couple dozen kids who attend the school. It was a good turnout for our small space, so people spilled out into the backyard, the side-yard, and, for the first time, the Play House ramp.

Although we designed the ramp for wheelchair access, it became immediately clear that for these kids it's something else: a racetrack! An incredibly fun, slightly dangerous racetrack. Ever since our ramp was finished, the kids on our block have used it almost daily as a hang out, a lunch spot, a bike/skateboard/scooter ramp, and a decidedly non-regulation badminton court. The kids play hide and seek, do their homework, babysit their siblings, and live out their daily kid dramas. Grown-ups also quickly began using the ramp as a bus stop for the self-organized transport vans people use to get to factory work, or as a place to take a private phone call or sneak a cigarette at night. One day before Eid al-Adha, I walked to the space and found two goats tethered to the ramp, grazing in the side-yard. I wasn’t particularly surprised—goats always make an appearance in the neighborhood in the days leading up to Eid al-Adha before disappearing into our collective bellies—but I had to admit I was impressed. The ramp made an excellent hitching post.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here