Craving the Outrageous

Theatricality and Theatricality

Following work on my PhD, I traveled to Brooklyn, New York in July 2014 to consider what the rest of my life might be. I am a writer of plays put on hold while academic writing took over and now I have no idea how to go about being a playwright in New York in the twenty-teens. To re-educate myself, I used my time in New York to see new plays and determine how or if my aesthetic had changed while in grad school.

Of the many plays I saw, I will concentrate on the following five: Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2, and 3 (Suzan Lori Parks), Grand Concourse (Heidi Schreck); Pocatello (Samuel D. Hunter); Our Lady of Kibeho (Katori Hall); and The Oldest Boy (Sara Ruhl). The list represents the order in which I saw the plays with Grand Concourse and Pocatello, the most realistic of the five—sandwiched between the more theatrical Parks, Hall, and Ruhl. With each play I saw, I questioned my interest in theatricality and what that term actually meant. Using Tracy C. Davis and Thomas Postlewait’s book Theatricality, I’ll apply the shifting definitions of that term to these particular five plays to explore why more theatricality was present in one play over others, how theatricality was used, and as a way to reconnect with my own preferences.

In their opening statement the authors explain, “One thing, but perhaps only one, is obvious: the idea of theatricality has achieved an extraordinary range of meanings, making it everything from an act to an attitude, a style to a semiotic system, a medium to a message.” This flexibility made it easier for me to not only examine my own expectations of theatricality, but also to begin to welcome new perspectives as to what the term means. The first play I saw, Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 and 3, by Suzan Lori Parks, falls under Davis and Postlewait’s category of theatricality as a style because theatricality is so much a part of the playwright’s technique.

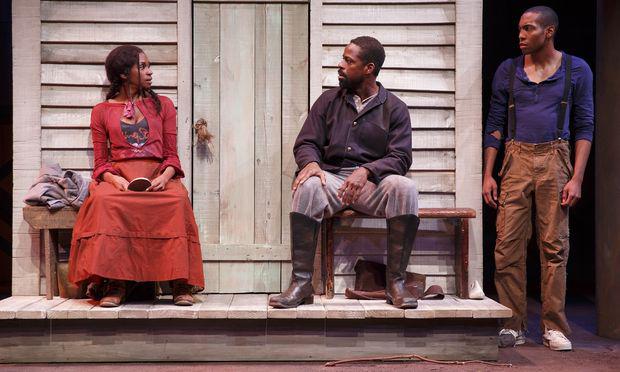

Father Comes Home From the Wars is written in Parks’s signature poetic text. Her poetry is particularly useful in this play because, though set during the Civil War, Parks has adapted the story from Homer. Not being an expert on the Odyssey, I won’t venture to compare it and the play too finely, but I will mention that the interplay of Parks’s story and Homer’s is part of what makes the play unrealistic and therefore theatrical. Direct address to the audience is used as a reminder that we are always watching theatre. There is an actor playing a dog in a costume that looks from head to toe like a large, well-used mop head. Parks’s poetry is a blend of normal speech, modern idioms (“True ‘dat!”) and repetition. By interweaving modern elements with the stage time of the mid-1800s there are continual signs that the debate on racism taking place in Civil War times is the same debate in the twenty-first century. In fact, the play gives an excellent lesson on the meaning of white privilege as delivered in a speech by the character of the Colonel in Part 2. The Colonel declares to his slave, Hero that he thanks God every day that he was born white and explains why his whiteness is valuable currency that will, no matter what else happens, always keep him on top in a racialized world.

Theatricality happens within the gap between reality and its representation, or mimesis, and is found in the ‘heightened states when everyday reality is exceeded by its representation.’

I saw the play with a diverse audience, but it was still at least three-quarters white. Theatricality, in this case, had a way of diverting the more serious message contained in portraying a slave who refuses to run away from his master because, as property, he believes it would make him a thief. With an audience that is primarily white, theatricality can make more accessible the larger point that from Civil War times until now we have not made as much progress as we think in terms of racial politics.

From Father Comes Home From the Wars I then saw two plays well grounded in realism: Grand Concourse and Pocatello. I thought, surely I would learn a lot from seeing both since the playwrights, Schreck and Hunter, are new and on a positive trajectory with their work—at least so far as “positive trajectory” means the ability to get one’s work produced. From seeing the two plays back to back I went away longing for more punch; more theatricality. But, as Davis and Postlewait help to illuminate, there is theatricality in realism. Realism is the genre most concerned with mimesis, or the imitation or representation of the real. Davis and Postlewait point out that theatricality happens within the gap between reality and its representation, or mimesis, and is found in the “heightened states when everyday reality is exceeded by its representation.”

Grand Concourse takes place in a soup kitchen in the Bronx. The set was meticulous in its realistic depiction of a functional working kitchen. Actors chop a few vegetables, put them in large pots and, as we are expected to believe, by the end of a short eight to ten-minute scene, produce enough soup, completely cooked and ready to serve to a crowd of homeless folks. The process requires the audience to pretend real time has not passed and replace it with a notion of theatre time and that more produce has gone into the pot than what the audience witnesses. This liberty by the playwright operates in the space between realism and audience reception where believability is stretched.

There was an audible gasp from the audience the day I saw the play when it was revealed the antagonist (Emma) is responsible for the death of the protagonist’s (Shelley’s) cat, Pumpkin. The death takes place when Shelley, who is a nun, leaves town to attend to her dying father. Shelley never, in the entire time she’s away, checks on the care of Pumpkin or how Emma, already proven to be unreliable, is handling the responsibility. We might, therefore, say that Shelley is also partially responsible for Pumpkin’s demise, although this is never discussed and Emma is fully blamed. Theatricality then becomes a plot device to manipulate the audience and, in the case of Pumpkin, works brilliantly. How far can a play go, within the context of realism and the attempt at mimesis, to play with the audience’s suspension of disbelief?

Theatricality tells us, “When the spectator’s role is not to recognize reality but to create an alternative through complicity—then both performer and spectator are complicit in the mimesis.” This bargain between representation and reception exists to further mimesis, however, “This complicity can be exhilarating, but it can also be disconcerting. It means that mimesis may not mislead.” This does not mean mimesis must become reality. Instead it means that in misleading the audience the bargain comes into question. Davis and Postlewait call this a “mimetic conundrum,” where, “performers and spectators are still true to themselves, though paradoxically the representation may lack truth.” Spectators may say “ah, we are now in ‘theatre’ time,” as I did when the soup was prepared. They may also be so shocked at an animal starving to death that they don’t immediately question all the ramifications. But this doesn’t mean there weren’t more questions to be asked of the plot that were never explored.

Pocatello is a plain play about plain people in a plain environment. The protagonist is Eddie, a sad sack who is as sad at the end of the play as he is at the beginning. The action takes place in a generic corporate Italian restaurant complete with phony grapevines and basketed bottles. The play creates as naturalistic and bland an atmosphere as the characters that are suffering in this small town in Idaho. Ironically, the set is metatheatrical, because it represents just the sort of pseudo Italian kitsch that many chain Italian restaurants use in the belief it helps transport their patrons to phony Italy.

Towards the end, when his restaurant is closed down and the other characters move on, it would be uplifting to believe that Eddie might also move on. Instead he sits at a table sobbing while his mother comforts him. The playwright gives no hint as to this depressed man’s fate. Pocatello doesn’t have the stretches in believability that Grand Concourse has, but if this is realism’s “artless art,” give me theatricality in its broadest sense any time.

Where was the play that was downright outrageous?

Our Lady of Kibeho and The Oldest Boy both represent what Davis and Postlewait mention as modernism’s “alternatives to realism,” insomuch as they reveal “realistic and nonrealistic qualities.” The book also quotes designer Mordecai Gorelik who explains, “Theatricalism is a modern neo-conventional stage form based on the principle that ‘theatre is theatre, not life,’” expanding the range of meaning to include using theatrical effects to enhance realism.

The premise of Our Lady of Kibeho is familiar to anyone who knows The Crucible or any variation on Joan of Arc. Young girls in Rwanda are having visions of the Holy Mother who forewarns the genocide to come in that beautiful country. It is a true story, as was The Crucible and Joan of Arc, but the conflict (is it all a hoax or not?) consumes the first act and has been heard before. The end of the first act, with its levitating bed, begins a series of special effects that continue through the second act, to spice up a tiresome, if poignant argument. In this case, theatricality is used as relief to a repetitive narrative, waking the audience up and soliciting a standing ovation. In contrast, the patron sitting beside me left at the end of the first act. If he’d known what was coming he might have stayed.

The Oldest Boy is also based on a true story. An American woman marries a Tibetan chef. They have a son who is identified as the incarnation of an important Buddhist Lama and is transported to Tibet to take his rightful place as a master. The play is about a mother losing her child but its style has an unrealistic atmosphere. Traditional dance and music are interspersed between scenes and a beautifully choreographed ceremony where the boy becomes the Lama is sumptuously costumed. A “baby” is delivered on stage and the addition of a puppet as the boy is ingenious because the actor who eventually embodies the boy as the deceased Lama animates the puppet. It is a reference to reincarnation while solving the problem of casting an extremely young child. As Davis and Postlewait examine the new meaning of theatricality in modernism they point out “the idea of theatricality could now be used to describe key attributes of both imagination and genius.” The Oldest Boy falls within this meaning as theatricality seeks to enhance the playwright’s message and portray an unfamiliar culture. Still, I was hoping for more theatricality and wondered why I wasn’t getting what I wanted. Where was the play that was downright outrageous? I finally found it and another lesson was learned.

I recently saw Charles Mee’s Big Love, a play that was so packed with theatricality I found myself wishing the shenanigans would stop so the story could be told. They did and it was, but in the restroom I heard two women complain that the show was too “talky” at the end, having no patience with Mee’s highly theatrical language after the circus-like presentation that preceded it. Again, Theatricality is a guide. The authors explain that theatricality is not necessarily one generalized theory but rather, “a historical methodology to be applied, case by case, to the unique features of each theatrical performance, seen from the perspective of a multiple number of spectators” So when I craved the outrageous, after my prior theatre-going history, I got it and was satisfied. My fellow spectators craved more. It is all in the perception of the receiver; therefore my insights to the previous five plays are mine alone. Theatricality has helped me organize my perspective and come to some conclusions as to what sort of theatre I want to pursue. The book helped wade through all the possibilities of what theatricality means and how it can be used. I know now I am more engaged when theatre is theatre and not life.

***

Davis, Tracy C. Thomas Postlewait. eds. Theatricality. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

An interesting article thanks for offering it. I tend to resonate with your last comment. The trick is to find the appropriate balance of the mode of theatricality serving the story at an optimum level. I did not see any of these productions. I did see 'The Curious Case . . . '. I had mixed feelings about the production. I was pretty much thrilled and amazed with the direction and production values, and yet by the end of the play did not feel as emotionally connected and involved with the story and characters as I wanted to. I felt this was primarily due to the 'theatricality' of 'presentation' [brilliant as it was] was not balanced with the story, but took center stage over it. Theatre is not life, as I believe you said somewhere in your article, but when the theatrical optimally reveals the story then the magic of theatre does in turn reveal something about life. And that has been and always will be its gift.

M.J. I too felt disconnected from the emotional life of "The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time," but I interpreted that disconnect on two levels. 1) It's a play for an intimate space, a black box or studio theatre, and not for a barn like the Barrymore--albeit a small theatre by Broadway standards, and 2) the resolution was wrapped up a little too quickly and neatly, relying on sentimentality where emotional ambiguity may have been more effective for catharsis.